Queer Futurity and Hybridity in Arrival and Embrace of the Serpent

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Performance Arrival Time 2019

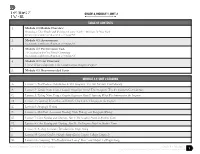

Arrival times for Performances of “The Accidental Stowaway” Please make every effort to stick to these times as they are designed to minimise congestion. YES to snacks, drinks and quiet activities to do. A dressing gown or comfortable clothing is also a good idea PLEASE NAME ALL CLOTHING, BOOKS, AND GAMES EQUIPMENT. NO to NUTS and SEEDS, noisy activities, and items that could ruin costumes such as chocolate, ribena, or chewing gum. NO to any photography or recording of any kind. NO to fitbits! Thursday (Purple) and Friday (Orange) Night at Harpenden Public Halls, Southdown Road 5:20: All Aboard (except Kids Playing) – Passengers – Cocktails – Sailors 5:3 0: Jobs – Kids Club – Chefs – Engineers – Chambermaids 5:45 : Spain – Gypsies – Convent School – Paso Doble – Spanish Ballet 6:00 : Mamma Mia – Honey honey – Dancing Queen – Slipping Through - Waterloo 6:10: Carnival and Cape Horn – Party Starters – Skeletons – Hummingbirds – Party Time! – Iceburg – Penguins - Albatross – Storm 6:20: Under the Sea and Captains Ball – Seahorses – Jellyfish – Scuba Divers – Coral – Ballroom 1 – Ballroom 2 – TV Show – Kids Playing All dancers* should be picked up at 9:30pm. See ‘Leaving Early’ form available from the website or registration team at rehearsals if you wish to pick up children Grade 2 and below at an earlier time. Saturday Matinee (Purple) at Harpenden Public Halls, Southdown Road 12:20: All Aboard (except Kids Playing) – Passengers – Cocktails – Sailors 12:30: Jobs – Kids Club – Chefs – Engineers – Chambermaids 12:45: Spain – Gypsies – Convent School – Paso Doble – Spanish Ballet 1:00: Mamma Mia – Honey honey – Dancing Queen – Slipping Through - Waterloo 1:10: Carnival and Cape Horn – Party Starters – Skeletons – Hummingbirds – Party Time! – Iceburg – Penguins - Albatross – Storm 1:20: Under the Sea and Captains Ball – Seahorses – Jellyfish – Scuba Divers – Coral – Ballroom 1 – Ballroom 2 – TV Show – Kids Playing All dancers should be picked up at 4:30pm. -

Signal Hill Elementary School

Half Hollow Hills Central School District SIGNAL HILL ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 670 Caledonia Road Dix Hills, NY 11746 631-592-3700 Parent / Student Handbook “Together We Can Make a Difference” Handbook Overview Some of the policies and procedures contained in this handbook come directly from district policies. District policies can be found in their entirety on the Half Hollow Hills Website at www.hhh.k12.ny.us . Some of the policies and procedures in this handbook only pertain to the Signal Hill Community. Many of our policies and procedures are intended to help students become more responsible and independent in preparation for experiences outside of school. We are very privileged to teach the students in the Signal Hill Community and our goal is to create a successful learning environment that accounts for all students’ needs. 2 Table of Contents Contact Information 4 Principal’s Message 5 Mission Statement 6 Hours/Attendance 7 Morning Arrival; Drop offs; Dismissal Pick-ups; Playdates; Absences Closings/Early Dismissal Parking Lot Traffic Pattern 10 Expectations for Bus Behavior 11 Health/Allergy Information 12 Breakfast/Lunch/Snack 14 Teaching and Learning 16 Curriculum; Specials; Band/Orchestra/Chorus Technology; Health; School Clubs Extra Learning; Parent/Teacher Conferences Support Services; Report Cards Testing; eBoards; Contacting Teachers REACH Program Homework Policy 19 General Policies 20 Visitors; Birthdays; Field Trips Cellphones / Electronic Devices Telephone Use; Lost and Found Items Left in School PTA/ BOE/ District-wide Administration -

A Congregation of Wintering Bald Eagles

SHORT COMMUNICATIONS 311 LITERATURE CITED mals in the canopy of a tropical rain forest. Malay. BAKER, E. C. S. 1927. The fauna of British India, in- For. 29: 182-203. cluding Ceylon and Burma, p. 357. Vol. 4. Taylor MCCLURE, H. E. 1977. The‘ secret life of a tree. Anim. and Francis, London. Kingdom 80: 16-23. CHASEN, F. N. 1939. The birds of the Malay Penin- MEDWAY, LORD. 1972. Phenology of a tropical rain sula, p. 126. Vol. 4. H. F. and G. Witherby, Lon- forest in Malaya. Biol. J, Linn. Sot. 4:117-146. don. PARKES, K. C. 1960. Geographic variations in the MADOC, G. C. 1947. An introduction to Malayan birds. Lesser Tree Swift. Condor 62:3-6. Malay. Nat. J. 2, parts 3 and 4. SHARPE, R. R. 1879. A list of the birds of Labuan Is- MADOC, G. C. 1956. An introduction to Malayan birds. land and its dependencies. Proc. Zool. Sot. Lond., Malayan Nat. Sot. and Caxton Press, Kuala Lum- p. 317-354. pur. SHELFORD, R. W. C. 1916. A naturalist in Borneo. MCCLURE, H. E. 1964. Some observations ofprimates London. in climax dipterocarp forest near Kuala Lumpur, Malaya. Primates 5:39-58. 69 East Loop Drioe, Camarillo, California 93010. Ac- MCCLUKE, H. E. 1966. Flowering, fruiting and ani- cepted for publication 29 September 1978. Condor, 81:311313 @ The Cooper Ornithological Society 1979 A CONGREGATION OF WINTERING able cover, but ornamental trees constitute most of the BALDEAGLES vegetation over 3 meters in height. The trees, mostly white and Lombardy poplars (Populus alba; Populus sp.), black locust (Robinia pseudacacia) and Siberian elm (Ulmus sp.), were planted as wind breaks or shade R. -

ARRIVAL in SYDNEY - Grant's Review

ARRIVAL IN SYDNEY - Grant's Review ARRIVAL - Simply Sensational Sensational. That’s the only word I can think of to describe the two ARRIVAL shows held in Sydney over the weekend. I am feeling quite lost for words and out of it today. A bit like feeling jet lagged. ARRIVAL are ABBA fans that much is obvious. The attention to detail, the respect, the song choices, the costumes everything is just so right and spot on. And no f##king cat dresses!!!!! As much as I loved the cat dresses way back when ABBA wore them, they have now become the symbol of cheap, tacky ABBA send-ups. ARRIVAL's 1977 tour costumes were just perfect and looked so real. The mini musical? I am lost for words. The narrator, the wigs, the choreography all perfect. Even at the best of times I really can’t get into “Thank You For The Music” but Anna (Agnetha) put in such an amazing vocal performance, I really sat up and took notice a more German cabaret type of vocal. Vicky’s (Frida) emotional rendition of “I Wonder” gave me goose bumps and a weird feeling inside. You often forget what an amazing song “I Wonder” is because the studio version is so flat and devoid of emotion. And “Marionette” really rocked. One of my favourite ABBA songs. :-) Singing in Swedish was a great touch. “Ring Ring (Bara Du Slog En Signal)” never sounded better. “Fernando” took on a new dimension hearing the first verse and chorus sung in Swedish as Frida's original version had been. -

NYS Common Core ELA Curriculum Grade 4 • Module 1 Copyright © 2012 by Expeditionary Learning, New York, NY

GRADE 4, MODULE 1, UNIT 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Module 4.1 Module Overview Becoming a Close Reader and Writing to Learn: Native Americans in New York See separate stand-alone document on EngageNY 2. Module 4.1: Assessments See separate stand-alone document on EngageNY 3. Module 4.1: Performance Task A Constitution for Our School Community See separate stand-alone document on EngageNY 4. Module 4.1 Unit Overview Unit 2: What is Important to the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois People)? 5. Module 4.1: Recommended Texts MODULE 4.1: UNIT 2 LESSONS A. Lesson 1: Text Features: Introduction to The Iroquois: The Six Nations Confederacy B. Lesson 2: Taking Notes Using a Graphic Organizer, Part I: The Iroquois: The Six Nations Confederacy C. Lesson 3: Taking Notes Using a Graphic Organizer, Part II: Inferring What Was Important to the Iroquois D. Lesson 4: Capturing Main Ideas and Details: How Life Is Changing for the Iroquois E. Lesson 5: Paragraph Writing F. Lesson 6: Mid-Unit Assessment: Reading, Note- Taking, and Paragraph Writing G. Lesson 7: Close Reading and Charting, Part I: The Iroquois People in Modern Times H. Lesson 8: Close Reading and Charting, Part II: The Iroquois People in Modern Times I. Lesson 9: Reading Literature: Introduction to Eagle Song J. Lesson 10: Central Conflict in Eagle Song (Revisit Chapter 1, Begin Chapter 2) K. Lesson 11: Comparing “The (Really) Great Law of Peace” and Chapter 3 of Eagle Song NYS Common Core ELA Curriculum Grade 4 • Module 1 Copyright © 2012 by Expeditionary Learning, New York, NY. -

Turf) Stk 125000 CORNWALLIS STAKES (GROUP 3) for Two Yrs Old 1 Only

International PP's Newmarket(ENG) Stk 125000 5 Furlongs (T) 2yo Friday, October 09, 2015 Race 1 WIN; PLACE; EXACTA; TRIFECTA; SWINGER 5 Furlongs. (Turf) Stk 125000 CORNWALLIS STAKES (GROUP 3) For two yrs old 1 only. Weights: Colts and geldings, 127 lbs, fillies 124 lbs. Penalties, a winner of a Group 3 race 3 lbs Of a Group 1 or Group 2 race 5 lbs Post Time: ( 8:35)/ 7:35/ 6:35/ 5:35 pp2 Adham ( NA 0) B. c. 2 (Apr) Life: 5 2 - 1 - 0 $15,076 Fst 0 0 - 0 - 0 $0 Sire : Dream Ahead (Diktat (GB)) $15,000 2015 5 2 - 1 - 0 $15,076 Off 0 0 - 0 - 0 $0 1 Own: Sheikh Rashid Dalmook Al Maktoum Dam: Leopard Creek (GB) (Whitebrush) 15/1 Yellow, Dark Blue Seams, Yellow Cap. Brdr: (IRE) 127 2014 0 0 - 0 - 0 $0 Dis 5 2 - 1 - 0 $14,946 Trnr: Tate James NEW 0 0 - 0 - 0 $0 Trf 5 2 - 1 - 0 $14,946 Morris L AW 0 0 - 0 - 0 $0 Sire Stats: AWD 6.0 Mud 0MudSts 18%Turf 15%1stT 1.84spi Dam'sSire: AWD 6.0 8%Mud 50MudSts Turf 1stT 0.41spi Dam'sStats: Unraced 1trfW 1str 1w 0sw1.25spi DATE TRK DIST RR RACETYPE CR Fin JOCKEY ODDS Top Finishers Comment 22Aug15 York(GB) à 5f gd :59¨ ¨¨ Hcp 92614 ¨¨© 8¨© CrowleyJ¨© 20.00 Shadow Hunter³RouleauƒKurlandƒ York(GB) 9 Julia Graves Roses Stakes 08-22-15 Awkwardly away in rear; ridden halfway; weakened over 1f out 22Jly15 Bath & Somerset County(GB) à *5f fm 1:02« ¨¨¬ Alw 9645 ¨¨® 1³ MorrisL¨ªª 0.67 Adh³SixtisS«SlvrWns´ Bath & Somerset County(GB) 3 Dribuild Ltd E B F Novice Stakes 07-22-15 Made all; ridden inside final furlong; just held on 10Jly15 Chepstow(GB) à *5f gd :58ª ¨¨ª Alw 14923 ¨¨ 2² MorrisL¨ªª 1.62 Receding Waves²Adham¨Silver -

Rock Album Discography Last Up-Date: September 27Th, 2021

Rock Album Discography Last up-date: September 27th, 2021 Rock Album Discography “Music was my first love, and it will be my last” was the first line of the virteous song “Music” on the album “Rebel”, which was produced by Alan Parson, sung by John Miles, and released I n 1976. From my point of view, there is no other citation, which more properly expresses the emotional impact of music to human beings. People come and go, but music remains forever, since acoustic waves are not bound to matter like monuments, paintings, or sculptures. In contrast, music as sound in general is transmitted by matter vibrations and can be reproduced independent of space and time. In this way, music is able to connect humans from the earliest high cultures to people of our present societies all over the world. Music is indeed a universal language and likely not restricted to our planetary society. The importance of music to the human society is also underlined by the Voyager mission: Both Voyager spacecrafts, which were launched at August 20th and September 05th, 1977, are bound for the stars, now, after their visits to the outer planets of our solar system (mission status: https://voyager.jpl.nasa.gov/mission/status/). They carry a gold- plated copper phonograph record, which comprises 90 minutes of music selected from all cultures next to sounds, spoken messages, and images from our planet Earth. There is rather little hope that any extraterrestrial form of life will ever come along the Voyager spacecrafts. But if this is yet going to happen they are likely able to understand the sound of music from these records at least. -

Abandoned Library Press 2

Abandoned Library Press 2 VIsion Editors’ Note “I had no sense of being seen or observed by anyone as I wrote. Perhaps this was a problem too.” Bhanu Kapil, Ban En Banlieue (Nightboat Books, 2015) The word ‘vision’ holds many meanings, especially in relation to art and literature. Sight. What is seen or isn’t. The way the eyes move inside the sockets, the way the lids press together, lashes entangle. The way color and light enter through a soft jellied hole, pinpricks leading to an infinity of signals shimmering around our brains. Vision is visibility—in writing, in life, in culture. Being seen in metaphors, in stereotypes, in cold cliches, in terms of how you perform gender your biological sex in terms of your body’s specificities or faults or beautiful differences. The pigmentation of the stuff that holds your insides in. Being seen as threat, being seen as other. Or, it is not being seen at all. Vision is also scope; dilation of time and intentions into particulate or infinitesimal stretches. It could mean hallucinations, transformations, slips of consciousness, dreams, faults in percep- tion, things forgotten, loaded silences, memories, future memories, held breathes, déjà vu. Issue 2 features twelve writers who each deal with the theme of vision in their own unique ways. Through poetry, hybrid essays, erasures and more, our authors show us there is more to vision than meets the eye. Read on. Kyle and Jenna MASTHEAD Editor-in-Chief Kyle Wright Visual Arts Editor Jenna Post IN THIS ISSUE Kristen Mitchell “NYC Scum” ................................................................ 3 “To Frank O’Hara’s Birthday Cake”....................... -

CDT Mamma Mia!

Jessica Fredrickson Act One Near the beach of a beautiful, small Greek island, a young woman, Sophie, mails three envelopes; one to Sam Carmichael, one to Bill Austin and one to Harry Bright. (“I Have a Dream”). Suddenly, two of Sophie’s old friends, Ali and Lisa, appear. They are there for a very special occasion: Sophie is getting married tomorrow! But even Sky, Sophie’s fiancé, doesn’t know the secret she now reveals to her friends: After reading her mom’s old diary, Sophie has learned that years ago, Sophie’s mother, Donna, knew three men, and one of them is Sophie’s father (“Honey, Honey”). It is these three men that Sophie has invited to her special day. It’s her dream to have her father give her away at her wedding. Just as Sophie is plotting with her friends, her mother, Donna, is reminiscing with her old pals, Rosie and Tanya, who have also come to the island for Sophie’s wedding. Donna, Rosie and Tanya were once the pop singing trio “Donna and the Dynamos.” Donna introduces her friends to Sophie’s fiancé, Sky, along with Pepper and Eddie, who work at Donna’s hotel/bar, the Taverna. Donna laments constantly working to run the Taverna (“Money, Money, Money”). As Donna and the girls exit, Sam, Harry and Bill arrive at the Taverna. They comment that it’s been twenty one years since they were last here, but none of them realize the significance. Sophie meets them and is shocked to see all three before her. -

11 October LP Release: Arrival

ABBA on record 11 October LP release: Arrival. Polar POLS 272. A: ‘When I Kissed The Teacher’; ‘Dancing Queen’; ‘My Love, My Life’; ‘Dum Dum Diddle’; ‘Knowing Me, Knowing You’. B: ‘Money, Money, Money’; ‘That’s Me’; ‘Why Did It Have To Be Me’; ‘Tiger’; ‘Arrival’. Note: ‘Fernando’, which was recorded at the same time as ‘Dancing Queen’, was featured on the Great- est Hits album in many territories and so not included on Arrival, except in Australia and New Zealand. ArrivAl, first releAsed in Sweden on 11 October 1976, was the first of ABBA’s albums to be hotly anticipated on a global level. Following on from the massive success enjoyed by the ‘Fernando’ single and the compilation albums variously entitled Greatest Hits or The Best Of ABBA – and notwithstanding the success of the ABBA album in some territories – the world was now truly holding its breath to see what ABBA would come up with next. As for the album sleeve, it’s not entirely clear what came first: the cover image fea- turing a helicopter or the title Arrival. What is clear is that the title came from Lillebil Ankarcrona, the then common-law wife of designer Rune Söderqvist. In more recent times, neither Lillebil nor Rune have been able to recall the order of the process – either the word “arrival” came first and then it was up to Rune to figure out a visual concept that would tie in to that title, or the designer thought of placing ABBA in a helicopter and then, having seen the photograph, Lillebil thought of the word “arrival”. -

Friday, July 13, 2018 Villa Milano, Columbus, Ohio

Friday, July 13, 2018 Villa Milano, Columbus, Ohio Arrival from Sweden is the world’s most popular and bestselling ABBA show band. Since the start of 1995, the production has toured over 60 nations and appeared in TV and radio shows all over the world. They have done 50 tours in the USA since 2005 and have played with over 60 symphony orchestras worldwide since 2007! Arrival from Sweden has the exclusive rights to copy ABBA's original outfits and permission to trademark ABBA in their production name ABBASOLUTELY - permitted by Universal. This 12-piece band (including some original members of ABBA's band) will take you back to the ‘70s as they re-create the appearance of the original stars that defined pop music. Authentic costumes, entrancing dance numbers and impeccable harmonies all come together to create the ABBA experience, live on stage. Arrival’s tongue-in-cheek retrospect of supergroup, ABBA, includes the four main band members, plus six side musicians & three female back-up singers. The group transports the audience back through the years while singing and dancing all of the ABBA favorites like Fernando, SOS, Mamma Mia, and Waterloo. The band doesn’t just perform songs popularized by the musical "Mamma Mia," but re-introduces the audience to some of Abba’s less well-known songs like Tiger, So Long. Our coach departs St. Michael’s parking lot at 9:30 am Friday morning heading to Villa Milano in Columbus, Ohio for lunch and the show ARRIVAL. St. Michael’s Church parking lot is located at 3534 St. -

CGT Abba Book AW

ABBA Original Sweden issue: Polar Music POLS 262, released April 21, 1975. First UK release: Epic EPC 80835, June 7, 1975 EW WOULD DISPUTE THE ARGUMENT THAT THIS ALBUM WAS THE F first wherein Abba became truly recognisable as Abba. There were hints of what was to come in the highlights on Ring Ring and Waterloo,but this was the first album to feature the soon-to-be-famous multi-layered Abba sound throughout.With one or two exceptions, it was also clear that the group had identified their strengths and their weaknesses, and reached some kind of understanding of what they really wanted to accomplish with their music. Although the finished album oozed confidence, Abba’s status in the international music world was actually a bit shaky when sessions started on August 22, 1974 (the studios used for the album were Glen Studio and Metronome Studio) and were even shakier when sessions finally concluded in March 1975. At the very least, this was the situation in the UK, which they regarded as the home of pop music and where, accordingly, they felt it was most important for them to succeed. The problem was an image tainted through having won the Eurovision Song Contest, which was widely derided for lacking integrity. “Groups like ours that had been tagged as ‘Eurovision’ were not meant to have more than one hit,”recalled Björn. The remixed ‘Ring Ring’ single, released as a follow-up to ‘Waterloo’, reached no higher than 32 on the UK chart. Then, in November 1974 when Abba released the first single from the current album sessions,‘So Long’,it tanked completely, failing to register on the chart.