FACTS About DRUGS: PSILOCYBIN (“Magic Mushrooms”)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hallucinogens - LSD, Peyote, Psilocybin, and PCP

Hallucinogens - LSD, Peyote, Psilocybin, and PCP Hallucinogenic compounds found in some • Psilocybin (4-phosphoryloxy-N,N- plants and mushrooms (or their extracts) dimethyltryptamine) is obtained from have been used—mostly during religious certain types of mushrooms that are rituals—for centuries. Almost all indigenous to tropical and subtropical hallucinogens contain nitrogen and are regions of South America, Mexico, and classified as alkaloids. Many hallucinogens the United States. These mushrooms have chemical structures similar to those of typically contain less than 0.5 percent natural neurotransmitters (e.g., psilocybin plus trace amounts of acetylcholine-, serotonin-, or catecholamine- psilocin, another hallucinogenic like). While the exact mechanisms by which substance. hallucinogens exert their effects remain • PCP (phencyclidine) was developed in unclear, research suggests that these drugs the 1950s as an intravenous anesthetic. work, at least partially, by temporarily Its use has since been discontinued due interfering with neurotransmitter action or to serious adverse effects. by binding to their receptor sites. This DrugFacts will discuss four common types of How Are Hallucinogens Abused? hallucinogens: The very same characteristics that led to • LSD (d-lysergic acid diethylamide) is the incorporation of hallucinogens into one of the most potent mood-changing ritualistic or spiritual traditions have also chemicals. It was discovered in 1938 led to their propagation as drugs of abuse. and is manufactured from lysergic acid, Importantly, and unlike most other drugs, which is found in ergot, a fungus that the effects of hallucinogens are highly grows on rye and other grains. variable and unreliable, producing different • Peyote is a small, spineless cactus in effects in different people at different times. -

Hallucinogens - LSD, Peyote, Psilocybin, and PCP

Information for Behavioral Health Providers in Primary Care Hallucinogens - LSD, Peyote, Psilocybin, and PCP What are Hallucinogens? Hallucinogenic compounds found in some plants and mushrooms (or their extracts) have been used— mostly during religious rituals—for centuries. Almost all hallucinogens contain nitrogen and are classified as alkaloids. Many hallucinogens have chemical structures similar to those of natural neurotransmitters (e.g., acetylcholine-, serotonin-, or catecholamine-like). While the exact mechanisms by which hallucinogens exert their effects remain unclear, research suggests that these drugs work, at least partially, by temporarily interfering with neurotransmitter action or by binding to their receptor sites. This InfoFacts will discuss four common types of hallucinogens: LSD (d-lysergic acid diethylamide) is one of the most potent mood-changing chemicals. It was discovered in 1938 and is manufactured from lysergic acid, which is found in ergot, a fungus that grows on rye and other grains. Peyote is a small, spineless cactus in which the principal active ingredient is mescaline. This plant has been used by natives in northern Mexico and the southwestern United States as a part of religious ceremonies. Mescaline can also be produced through chemical synthesis. Psilocybin (4-phosphoryloxy-N, N-dimethyltryptamine) is obtained from certain types of mushrooms that are indigenous to tropical and subtropical regions of South America, Mexico, and the United States. These mushrooms typically contain less than 0.5 percent psilocybin plus trace amounts of psilocin, another hallucinogenic substance. PCP (phencyclidine) was developed in the 1950s as an intravenous anesthetic. Its use has since been discontinued due to serious adverse effects. How Are Hallucinogens Abused? The very same characteristics that led to the incorporation of hallucinogens into ritualistic or spiritual traditions have also led to their propagation as drugs of abuse. -

Hallucinogens and Dissociative Drugs

Long-Term Effects of Hallucinogens See page 5. from the director: Research Report Series Hallucinogens and dissociative drugs — which have street names like acid, angel dust, and vitamin K — distort the way a user perceives time, motion, colors, sounds, and self. These drugs can disrupt a person’s ability to think and communicate rationally, or even to recognize reality, sometimes resulting in bizarre or dangerous behavior. Hallucinogens such as LSD, psilocybin, peyote, DMT, and ayahuasca cause HALLUCINOGENS AND emotions to swing wildly and real-world sensations to appear unreal, sometimes frightening. Dissociative drugs like PCP, DISSOCIATIVE DRUGS ketamine, dextromethorphan, and Salvia divinorum may make a user feel out of Including LSD, Psilocybin, Peyote, DMT, Ayahuasca, control and disconnected from their body PCP, Ketamine, Dextromethorphan, and Salvia and environment. In addition to their short-term effects What Are on perception and mood, hallucinogenic Hallucinogens and drugs are associated with psychotic- like episodes that can occur long after Dissociative Drugs? a person has taken the drug, and dissociative drugs can cause respiratory allucinogens are a class of drugs that cause hallucinations—profound distortions depression, heart rate abnormalities, and in a person’s perceptions of reality. Hallucinogens can be found in some plants and a withdrawal syndrome. The good news is mushrooms (or their extracts) or can be man-made, and they are commonly divided that use of hallucinogenic and dissociative Hinto two broad categories: classic hallucinogens (such as LSD) and dissociative drugs (such drugs among U.S. high school students, as PCP). When under the influence of either type of drug, people often report rapid, intense in general, has remained relatively low in emotional swings and seeing images, hearing sounds, and feeling sensations that seem real recent years. -

Hallucinogens

Hallucinogens What Are Hallucinogens? Hallucinogens are a diverse group of drugs that alter a person’s awareness of their surroundings as well as their thoughts and feelings. They are commonly split into two categories: classic hallucinogens (such as LSD) and dissociative drugs (such as PCP). Both types of hallucinogens can cause hallucinations, or sensations and images that seem real though they are not. Additionally, dissociative drugs can cause users to feel out of control or disconnected from their body and environment. Some hallucinogens are extracted from plants or mushrooms, and others are synthetic (human-made). Historically, people have used hallucinogens for religious or healing rituals. More recently, people report using these drugs for social or recreational purposes. Hallucinogens are a Types of Hallucinogens diverse group of drugs Classic Hallucinogens that alter perception, LSD (D-lysergic acid diethylamide) is one of the most powerful mind- thoughts, and feelings. altering chemicals. It is a clear or white odorless material made from lysergic acid, which is found in a fungus that grows on rye and other Hallucinogens are split grains. into two categories: Psilocybin (4-phosphoryloxy-N,N-dimethyltryptamine) comes from certain classic hallucinogens and types of mushrooms found in tropical and subtropical regions of South dissociative drugs. America, Mexico, and the United States. Peyote (mescaline) is a small, spineless cactus with mescaline as its main People use hallucinogens ingredient. Peyote can also be synthetic. in a wide variety of ways DMT (N,N-dimethyltryptamine) is a powerful chemical found naturally in some Amazonian plants. People can also make DMT in a lab. -

MDMA Get 24/7 Help Now!

MDMA Illicit substances can be categorized into one of three major drug types: depressants, stimulants, and hallucinogens. Depressants consist of substances that slow or “depress” the body’s normal functions. In contrast, stimulants do the opposite: they jump-start the central nervous system, increasing the user’s heart rate, blood pressure, respiration and body temperature. Hallucinogens are unlike either of the other illicit drug groups; as the name suggests, these are drugs that cause hallucinations, whether visual or auditory. Sometimes, illicit drugs can fall into two of these three categories. Methylenedioxy-methamphetamine, more commonly called MDMA, is one such example. It falls into two categories: stimulant and hallucinogen. MDMA drug addiction is one type of addiction treatment available through the Wellness Retreat Recovery program. Get 24/7 help now! All calls are free and confidential! 888-821-0238 MDMA About MDMA Like any other stimulant, MDMA increases the user’s energy, blood pressure, heart rate, and respiration. Still, MDMA stands apart from other stimulant drugs because it triggers a number of effects that are more common among hallucinogens. In fact, MDMA is most well-known for being the active ingredient in Ecstasy, a “club drug” that distorts the user’s senses and evokes uninhibited feelings of sensuality. Other effects include: increased sensory reception (i.e. fabric seems softer, drinks taste stronger, etc.) increased sensitivity to light emotional exacerbation sexual arousal Overall, MDMA has been known to intensity users’ emotional and physical experiences. However, this does not make MDMA a “safe” drug as many users might argue. The Effects of MDMA on the Brain Just like with any other illicit substance, continued use of MDMA can lead to addiction. -

Psilocybin Mushrooms Fact Sheet

Psilocybin Mushrooms Fact Sheet January 2017 What are psilocybin, or “magic,” mushrooms? For the next two decades thousands of doses of psilocybin were administered in clinical experiments. Psilocybin is the main ingredient found in several types Psychiatrists, scientists and mental health of psychoactive mushrooms, making it perhaps the professionals considered psychedelics like psilocybin i best-known naturally-occurring psychedelic drug. to be promising treatments as an aid to therapy for a Although psilocybin is considered active at doses broad range of psychiatric diagnoses, including around 3-4 mg, a common dose used in clinical alcoholism, schizophrenia, autism spectrum disorders, ii,iii,iv research settings ranges from 14-30 mg. Its obsessive-compulsive disorder, and depression.xiii effects on the brain are attributed to its active Many more people were also introduced to psilocybin metabolite, psilocin. Psilocybin is most commonly mushrooms and other psychedelics as part of various found in wild or homegrown mushrooms and sold religious or spiritual practices, for mental and either fresh or dried. The most popular species of emotional exploration, or to enhance wellness and psilocybin mushrooms is Psilocybe cubensis, which is creativity.xiv usually taken orally either by eating dried caps and stems or steeped in hot water and drunk as a tea, with Despite this long history and ongoing research into its v a common dose around 1-2.5 grams. therapeutic and medical benefits,xv since 1970 psilocybin and psilocin have been listed in Schedule I of the Controlled Substances Act, the most heavily Scientists and mental health professionals criminalized category for drugs considered to have a consider psychedelics like psilocybin to be “high potential for abuse” and no currently accepted promising treatments as an aid to therapy for a medical use – though when it comes to psilocybin broad range of psychiatric diagnoses. -

Hallucinogens

Hallucinogens What are hallucinogens? Hallucinogens are a diverse group of drugs that alter a person’s awareness of their surroundings as well as their own thoughts and feelings. They are commonly split into two categories: classic hallucinogens (such as LSD) and dissociative drugs (such as PCP). Both types of hallucinogens can cause hallucinations, or sensations and images that seem real though they are not. Additionally, dissociative drugs can cause users to feel out of control or disconnected from their body and environment. Some hallucinogens are extracted from plants or mushrooms, and some are synthetic (human- made). Historically, people have used hallucinogens for religious or healing rituals. More recently, people report using these drugs for social or recreational purposes, including to have fun, deal with stress, have spiritual experiences, or just to feel different. Common classic hallucinogens include the following: • LSD (D-lysergic acid diethylamide) is one of the most powerful mind-altering chemicals. It is a clear or white odorless material made from lysergic acid, which is found in a fungus that grows on rye and other grains. LSD has many other street names, including acid, blotter acid, dots, and mellow yellow. • Psilocybin (4-phosphoryloxy-N,N- dimethyltryptamine) comes from certain types of mushrooms found in tropical and subtropical regions of South America, Mexico, and the United States. Some common names for Blotter sheet of LSD-soaked paper squares that users psilocybin include little smoke, magic put in their mouths. mushrooms, and shrooms. Photo by © DEA • Peyote (mescaline) is a small, spineless cactus with mescaline as its main ingredient. Peyote can also be synthetic. -

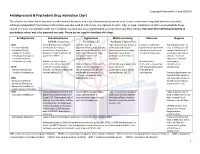

Antidepressant & Psychedelic Drug Interaction Chart

Copyright Psychedelic School 8/2020 Antidepressant & Psychedelic Drug Interaction Chart This chart is not intended to be used to make medical decisions and is for informational purposes only. It was constructed using data whenever possible, although extrapolation from known information was also used to inform risk. Any decision to start, stop, or taper medication and/or use psychedelic drugs should be made in conjunction with your healthcare provider(s). It is recommended to not perform any illicit activity. This chart the intellectual property of psychedelic school and is for personal use only. Please do not copy or distribute this chart. Antidepressant Phenethylamines Tryptamines MAOI-containing Ketamine Ibogaine -MDMA, mescaline -Psilocybin, LSD -Ayahuasca, Syrian Rue SSRIs Taper & discontinue at least 2 Consider taper & Taper & discontinue at least 2 Has been studied and Taper & discontinue at · Paroxetine (Paxil) weeks prior (all except discontinuation at least 2 weeks weeks prior (all except found effective both with least 2 weeks prior (all · Sertraline (Zoloft) fluoxetine) or 6 weeks prior prior (all except fluoxetine) or 6 fluoxetine) or 6 weeks prior and without concurrent except fluoxetine) or 6 · Citalopram (Celexa) (fluoxetine only) due to loss of weeks prior (fluoxetine only) (fluoxetine only) due to use of antidepressants weeks prior (fluoxetine · Escitalopram (Lexapro) psychedelic effect due to potential loss of potential risk of serotonin only) due to risk of · Fluxoetine (Prozac) psychedelic effect syndrome additive QTc interval · Fluvoxamine (Luvox) MDMA is unable to cause Recommended prolongation, release of serotonin when the Chronic antidepressant use may Life threatening toxicities can to be used in conjunction arrhythmias, or SPARI serotonin reuptake pump is result in down-regulation of occur with these with oral antidepressants cardiotoxicity · Vibryyd (Vilazodone) blocked. -

Ce4less.Com Ce4less.Com Ce4less.Com Ce4less.Com Ce4less.Com Ce4less.Com Ce4less.Com

Hallucinogens And Dissociative Drug Use And Addiction Introduction Hallucinogens are a diverse group of drugs that cause alterations in perception, thought, or mood. This heterogeneous group has compounds with different chemical structures, different mechanisms of action, and different adverse effects. Despite their description, most hallucinogens do not consistently cause hallucinations. The drugs are more likely to cause changes in mood or in thought than actual hallucinations. Hallucinogenic substances that form naturally have been used worldwide for millennia to induce altered states for religious or spiritual purposes. While these practices still exist, the more common use of hallucinogens today involves the recreational use of synthetic hallucinogens. Hallucinogen And Dissociative Drug Toxicity Hallucinogens comprise a collection of compounds that are used to induce hallucinations or alterations of consciousness. Hallucinogens are drugs that cause alteration of visual, auditory, or tactile perceptions; they are also referred to as a class of drugs that cause alteration of thought and emotion. Hallucinogens disrupt a person’s ability to think and communicate effectively. Hallucinations are defined as false sensations that have no basis in reality: The sensory experience is not actually there. The term “hallucinogen” is slightly misleading because hallucinogens do not consistently cause hallucinations. 1 ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com ce4less.com How hallucinogens cause alterations in a person’s sensory experience is not entirely understood. Hallucinogens work, at least in part, by disrupting communication between neurotransmitter systems throughout the body including those that regulate sleep, hunger, sexual behavior and muscle control. Patients under the influence of hallucinogens may show a wide range of unusual and often sudden, volatile behaviors with the potential to rapidly fluctuate from a relaxed, euphoric state to one of extreme agitation and aggression. -

Lysergic Acid Diethylamide (LSD) Promotes Social Behavior Through Mtorc1 in the Excitatory Neurotransmission

Lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) promotes social behavior through mTORC1 in the excitatory neurotransmission Danilo De Gregorioa,b,1, Jelena Popicb,2,3, Justine P. Ennsa,3, Antonio Inserraa,3, Agnieszka Skaleckab, Athanasios Markopoulosa, Luca Posaa, Martha Lopez-Canula, He Qianzia, Christopher K. Laffertyc, Jonathan P. Brittc, Stefano Comaia,d, Argel Aguilar-Vallese, Nahum Sonenbergb,1,4, and Gabriella Gobbia,f,1,4 aNeurobiological Psychiatry Unit, Department of Psychiatry, McGill University, Montreal, QC, Canada, H3A 1A1; bDepartment of Biochemistry, McGill University, Montreal, QC, Canada, H3A 1A3; cDepartment of Psychology, McGill University, Montreal, QC, Canada, H3A 1B1; dDivision of Neuroscience, Vita Salute San Raffaele University, 20132 Milan, Italy; eDepartment of Neuroscience, Carleton University, Ottawa, ON, Canada, K1S 5B6; and fMcGill University Health Center, Montreal, QC, Canada, H3A 1A1 Contributed by Nahum Sonenberg, November 10, 2020 (sent for review October 5, 2020; reviewed by Marc G. Caron and Mark Geyer) Clinical studies have reported that the psychedelic lysergic acid receptor (6), but also displays affinity for the 5-HT1A receptor diethylamide (LSD) enhances empathy and social behavior (SB) in (7–9). Several studies have demonstrated that LSD modulates humans, but its mechanism of action remains elusive. Using a glutamatergic neurotransmission and, indirectly, the α-amino- multidisciplinary approach including in vivo electrophysiology, 3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazole propionate (AMPA) receptors. optogenetics, behavioral paradigms, and molecular biology, the Indeed, in vitro studies have shown that LSD increased the ex- effects of LSD on SB and glutamatergic neurotransmission in the citatory response of interneurons in the piriform cortex following medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) were studied in male mice. -

Psychedelics in Psychiatry: Neuroplastic, Immunomodulatory, and Neurotransmitter Mechanismss

Supplemental Material can be found at: /content/suppl/2020/12/18/73.1.202.DC1.html 1521-0081/73/1/202–277$35.00 https://doi.org/10.1124/pharmrev.120.000056 PHARMACOLOGICAL REVIEWS Pharmacol Rev 73:202–277, January 2021 Copyright © 2020 by The Author(s) This is an open access article distributed under the CC BY-NC Attribution 4.0 International license. ASSOCIATE EDITOR: MICHAEL NADER Psychedelics in Psychiatry: Neuroplastic, Immunomodulatory, and Neurotransmitter Mechanismss Antonio Inserra, Danilo De Gregorio, and Gabriella Gobbi Neurobiological Psychiatry Unit, Department of Psychiatry, McGill University, Montreal, Quebec, Canada Abstract ...................................................................................205 Significance Statement. ..................................................................205 I. Introduction . ..............................................................................205 A. Review Outline ........................................................................205 B. Psychiatric Disorders and the Need for Novel Pharmacotherapies .......................206 C. Psychedelic Compounds as Novel Therapeutics in Psychiatry: Overview and Comparison with Current Available Treatments . .....................................206 D. Classical or Serotonergic Psychedelics versus Nonclassical Psychedelics: Definition ......208 Downloaded from E. Dissociative Anesthetics................................................................209 F. Empathogens-Entactogens . ............................................................209 -

Hallucinogenic Mushrooms: a Guide

Hallucinogenic Mushrooms: A Guide Presented by the Hamre Center for Health and Wellness Table of Contents Introduction Harm Reduction What are Hallucinogenic Mushrooms? What are the U.S. and MN Laws Surrounding Mushrooms? What Kinds of Hallucinogenic Mushrooms are There? How are Hallucinogenic Mushrooms Ingested? How Do Hallucinogenic Mushrooms Affect the Brain? What are Some Short-Term Effects of Use? What are Some Long-Term Effects of Use? How Do Hallucinogenic Mushrooms Interact with Alcohol? What are Some Harm-Reduction Strategies for Use? Are Hallucinogenic Mushrooms Addictive? What are Some Substance Abuse Help Resources? Introduction Welcome to the Hamre Center’s hallucinogenic mushrooms guide! Thank you for wanting to learn more about “magic mushrooms” and how they can affect you. This guide is designed to be a science-based resource to help inform people about hallucinogenic mushrooms. We use a harm-reduction model, which we’ll talk about more in the next slide. If you have any concerns regarding your own personal health and mushrooms, we strongly recommend that you reach out to your health care provider. No matter the legal status of hallucinogenic mushrooms in your state or country, health care providers are confidential resources. Your health is their primary concern. Harm Reduction ● The harm reduction model used in this curriculum is about neither encouraging or discouraging use; at its core, harm reduction simply aims to minimize the negative consequences of behaviors. ● Please read through the Hamre Center’s statement on use and harm reduction below: “The Hamre Center knows pleasure drives drug use, not the avoidance of harm.