George Mason University, Doing Digital History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Extensions of Remarks E1521 EXTENSIONS of REMARKS

September 8, 2004 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — Extensions of Remarks E1521 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS CITY OF SOUTHLAKE RANKED IN mother fell unconscious while on a shopping percent and helped save 1,026 lives. Blood TOP TEN trip. Bobby freed himself from the car seat and donors like Beth Groff truly give the gift of life. tried to help her. The young hero stayed calm, She has graciously donated 18 gallons of HON. MICHAEL C. BURGESS showed an employee where his grandmother blood. OF TEXAS was, and gave valuable information to the po- John D. Amos II and Luis A. Perez were lice. While on his way to school, Mike two residents of Northwest Indiana who sac- IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Spurlock came upon an accident scene. As- rificed their lives during Operation Iraqi Free- Tuesday, September 7, 2004 sisted by other heroic citizens, Mike broke out dom, and their deaths come as a difficult set- Mr. BURGESS. Mr. Speaker, it is my great one of the automobile’s windows and removed back to a community already shaken by the honor to recognize five communities within my the badly injured victim from the car. After the realities of war. These fallen soldiers will for- district for being acknowledged as among the incident, he continued on to school as usual to ever remain heroes in the eyes of this commu- ‘‘Top Ten Suburbs of the Dallas-Fort Worth take his final exam. nity, and this country. Area,’’ by D Magazine, a regional monthly The Red Cross is also recognizing the fol- I would like to also honor Trooper Scott A. -

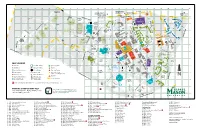

GMU-Fairfax-Campus-Map-2021.Pdf

A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z NO ENTRY NO EXIT EXIT NO Rapidan River Rd UNIVERSITY DRIVE TO: University Park Intramural Fields Mason Enterprise Center Commerce Building OX ROAD/ROUTE 123 TO: 4301 University Dr. 4087 University Dr. University Townhouse Complex 9 ROBERTS ROAD TO: 4260 Chain Bridge Rd. Tallwood 4210 Roberts Road R E V I KR C O N N A H A P P A 1 Student Townhouses 47 UNIVERSITY DRIVE UNIVERSITY DRIVE VE Reserved Parking GEORGE MASON BLVD S DR I PU M Field #1 LOT P A 35 C General Permit A Q 42 Parking U CO T S W OL I I D Rappahannock River A A S R H Parking Deck C C I 96 N L Spuhler Field L L LOT O R 38 L L D E 45 A A General Permit E 2 N O Mesocosm K R EVESHAM LANE E Parking Research BREDEN HILL LANE R L P ATRIOT CIRCLE Area A E PATRIOT CIRCLE N 39 V CHESAPEAKE RIVER LANE PERSHORE LANE I E R LOT M N Tennis CAMPUS DRIVE 23 97 Pilot A Softball General 63 62 Courts D House I Stadium Field House P Stadium Permit 98 D A Parking WEST CAMPUS WAY R LOT I Finley 61 3 Reserved Lot 69 OA Parking 34 S R 24 T Field #3 16 R Wotring 60 Courtyard 70 E OX ROAD/ROUTE 123 E B C A M P U S D R I V E L 56 C 65 STAFFORDSHIRE LANE R 20 I 71 51 49 RO C 21 BUFFALO CREEK CT T 58 72 4 O 33 Field #4 I 77 R 19 Maintenance T 64 WES T RAC A Storage Yard 6 Throwing CAMPUS DRIVE P 78 CA MPU S Fields Field 2 76 68 AY PA R K I N G 73 W LO T D 22 ROCKFISH CREEK LANE R 75 E Faculty/Staff Parking IV 74 R 53 66 8 57 SUB I NA Lot T N 5 5 31 E VA RIV 28 I CA US D AQUIA CREEK LANE R M P 67 Field #5 59 Y Kelly II A W NNA RI V E R 32 CAMPUS DRIVE A IV BRADDOCK ROAD/RT 620 PV LO T 10 R 27 KELLEY DRIVE General Parking 55 SHENANDOAH RIVER LANE 48 13 The Hub MASON POND DRVE 41 6 GLOBAL LANE RAC Mason Pond 25 Parking Deck BANISTER CREEK CT. -

Guide for International Students Why Choose George Mason University?

Guide for International Students Why Choose George Mason University? Make World-Changing Discoveries Tier 1 #14 1st Research Institute 1 of 81 Public Universities with Washington, DC, ranks #1 Carnegie Foundation's Tier 1 for the most STEM jobs in Highest Research Activity Most Innovative School a major US metro region (Carnegie Classification of Institutions of Higher Education) (U.S. News & World Report 2017) (AIER College Destinations Index 2016) #22 #12 Safest Campus Most Diverse University in the US in the United States (U.S. News & World Report 2018) (National Council for Home Safety and Security 2017) Ranked #22 45 minutes Nationwide for Top Internship Opportunities Outside of Washington, DC (The Princeton Review 2016) Employability at George Mason University Mason graduates are employed by many top companies, including: 84% 76% Boeing Lockheed Martin of employed students of Mason students are Volkswagen Accenture are in positions related employed within six Freddie Mac Marriott International to their career goals months of graduation Ernst & Young IBM (Mason Career Plans Survey 2016) (Mason Career Plans Survey 2016) 2 | INTO George Mason University 2018–2019 Top Programs GRADUATE #7 #17 #20 #27 Cybersecurity Special Education Criminology Systems Engineering (Ponemon Institute 2014) (U.S. News & World Report 2016) (U.S. News & World Report 2016) (U.S. News & World Report 2018) #33 #33 #64 #67 Economics Healthcare Public Policy Analysis Computer Science (U.S. News & World Report 2016) Management (U.S. News & World Report 2018) (U.S. News & World Report 2018) (U.S. News & World Report 2018) UNIVERSITY* #68 #78 #110 #140 Top Public Best Undergraduate Best Undergraduate in National Schools Business Programs Engineering Programs Universities *U.S. -

USC Digital Voltaire: Centering Digital Humanities in the Traditions of Library and Archival Science

USC Digital Voltaire: Centering Digital Humanities in the Traditions of Library and Archival Science FEATURE: WORTH NOTING USC Digital Voltaire: Centering Digital Humanities in the Traditions of Library 19.1. and Archival Science portal Danielle Mihram and Curtis Fletcher publication, abstract: USC Digital Voltaire, a digital, multimodal critical edition of autograph letters, aims to combine the traditional scope of humanities inquiry with the affordancesfor and methodologies of digital scholarship, and to support scholarly inquiry at all levels, beyond the disciplines associated with Voltaire and the Enlightenment. Digital editing, and digital editions in particular, will likely expand in the next few decades as a multitude of assets become digitized and made available as online collections. One important question is: What role will librarians and archivists play in this era? USC Digital Voltaire points in one possible, creativeaccepted direction. and Voltaire’s Autograph Letters at USC edited, t the University of Southern California (USC) Special Collections Department, researchers can findcopy 31 original (autograph) letters and four poems covering the years 1742 to 1777 by Voltaire, the pen name of François-Marie Arouet, A1694–1778. Voltaire’s clear writing style, humor, and sharp intelligence made him one of the greatest writers of the French Enlightenment, a period of intellectual ferment in the late 17th and the 18th centuries. His correspondents included other leading figures of the Enlightenment,reviewed, such as the mathematician and philosopher Jean le Rond d’Alembert; Frederick II (Frederick the Great), king of Prussia; and Madame de Pompadour, the mistresspeer of King Louis XV of France. Voltaire’s voluminous correspondence currently comprisesis over 22,000 published letters, of which 16,136 are by Voltaire.1 The correspon- dence offers a multifaceted, private, and, at times, moving expression of the writer’s mss.innermost thoughts and feelings, through epistolary exchanges. -

Rediscovering the State Constitutional Right to Happiness and Safety Joseph R

Hastings Constitutional Law Quarterly Volume 25 Article 1 Number 1 Fall 1997 1-1-1997 Rediscovering the State Constitutional Right to Happiness and Safety Joseph R. Grodin Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/ hastings_constitutional_law_quaterly Part of the Constitutional Law Commons Recommended Citation Joseph R. Grodin, Rediscovering the State Constitutional Right to Happiness and Safety, 25 Hastings Const. L.Q. 1 (1997). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_constitutional_law_quaterly/vol25/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings Constitutional Law Quarterly by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ARTICLE Rediscovering the State Constitutional Right to Happiness and Safety By JOSEPH R. GRODIN* Most people, at least most lawyers, are aware that of the trilogy of rights made famous by the Declaration of Independence-life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness-only the first two made it into the Federal Con- stitution, felicity giving way, in the Fifth Amendment's due process clause, to a more sober concern for the rights of property.1 What most people, even most lawyers, are less likely to know is that fully two thirds of the state constitutions contain provisions which either declare the right of per- sons to pursue happiness or (along with safety) to actually "obtain" it. Scholars, as well as lawyers, have tended to ignore these state consti- tutional provisions, apparently regarding them as little more than pious echoes of the Declaration. -

New and Renewing BFU Awards in 2019

League of American Bicyclists Bicycle Friendly University 2019 New and Renewing Awards Student 2019 College / University Award BFU Since City State Enrollment Status 00Platinum Platinum 0 . Colorado State University Platinum 2011 28,691 Fort Collins Colorado Renewal Portland State University Platinum 2011 27,670 Portland Oregon Renewal Stanford University Platinum 2011 20,069 Stanford California Renewal University of California, Irvine Platinum 2011 36,032 Irvine California Moved Up University of California, Santa Barbara Platinum 2011 25,145 Santa Barbara California Moved Up University of Wisconsin - Madison Platinum 2011 44,000 Madison Wisconsin Moved Up 00Gold Gold 0 . Purdue University Gold 2015 43,411 West Lafayette Indiana Moved Up The University of Arkansas Gold 2016 27,558 Fayetteville Arkansas Moved Up University of Arizona Gold 2011 45,217 Tucson Arizona Renewal University of California, Los Angeles Gold 2011 45,930 Los Angeles California Moved Up University of Wisconsin - Milwaukee Gold 2013 21,570 Milwaukee Wisconsin Renewal 00Silver Silver 0 . Auburn University Silver 2015 30,440 Auburn Alabama Renewal Coastal Carolina University Silver 2015 10,641 Conway South Carolina Moved Up George Mason University, Fairfax Campus Silver 2011 30,436 Fairfax Virginia Moved Up Southern Oregon University Silver 2016 4,268 Ashland Oregon Renewal The Ohio State University Silver 2011 61,170 Columbus Ohio Moved Up University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Silver 2011 43,649 Urbana Illinois Moved Up University of Massachusetts Lowell Silver 2015 18,257 Lowell Massachusetts Moved Up University of Michigan Ann Arbor Silver 2012 46,002 Ann Arbor Michigan Renewal Virginia Tech Silver 2013 34,850 Blacksburg Virginia Moved Up 00Bronze Bronze 0 . -

Why Does Freedom Wax and Wane? Some Research Questions in Social Change and Big Government

Why Does Freedom Wax and Wane? Some Research Questions in Social Change and Big Government Tyler Cowen Tyler Cowen. “Why Does Freedom Wax and Wane? Some Research Questions in Social Change and Big Government.” Mercatus Working Paper, Mercatus Center at George Mason University, Arlington, VA, 2000. ABSTRACT The 20th century has seen some of the greatest restrictions on liberty of any period in human history, as well as significant liberalizations and improvements. These questions do not always hold a central place in mainstream academic dis- course, but there are scholars who seek to explain how and why these changes have occurred. This paper attempts to make this research accessible to a broader audience. It presents relevant research on social change and concludes that Western societies are not headed off the proverbial economic cliff. Even though governments may be larger and more bureaucratic than before, they largely con- tinue to support freedom because failure to do so could destroy the entire system. Moreover, market-oriented economies have demonstrated a lasting ability to out- compete alternatives, such as communism. Technological changes and advance- ments hold a promise for greater freedom and prosperity across the world. JEL codes: B25, B59, D72, H10, H60, K10, L51, 057, P11, P16, Q58 Keywords: classical liberalism, constitution, corporations, deregulation, economic development, environmental regulation, free market, globalization, liberty, mass media, New Zealand miracle, public choice, rational irrationality, social change, Thatcher revolution, Tullock paradox, Westminster system AUTHOR’S NOTE Mercatus first put this piece out in 2000. We all thought it was worthwhile to revisit these issues, given the uncertain course of liberty in today’s world. -

About This Book

About Th is Book Th e next chapter is autobiographical. I narrate things from which the present volume emerged. ( 23 ) 003_Klein_Ch03.indd3_Klein_Ch03.indd 2233 111/21/20111/21/2011 88:49:05:49:05 PMPM CHAPTER 3 From a Raft in the Currents of Liberal Economics owadays, we see a trend toward disregarding disciplinary boundaries Nand admitting that in our policy judgment, as expressed, for exam- ple, in statements about economic effi ciency, there is something akin to aesthetic judgment. Th ere is a trend toward admitting that economics is inherently less precise and less accurate than some had thought. I grew up in Bergen County, New Jersey, outside of New York City, in a family that was Jewish but not religious, and Democratic and “liberal” in the fashion common to such folk. My father, a pediatrician, is now retired. My mother, now deceased for some time, left the house after the divorce and turned entrepreneur when I was ten, but she by no means left her four sons. At age thirteen, though not the least bookish, I was put in the smart eighth-grade class at the public school. Gradually, I became friendly with a classmate of very prodigious intellect. We shared interests in music and in our classmates and teachers. I read nothing, but I did know one thing: I disliked school. I had enjoyed kindergarten and fi rst grade, but from sec- ond grade, I was not inspired by the teachers, and I resented being pressed into their programs. With each year it had gotten worse. My friend’s political inclinations were unconventional, but I scarcely knew how advanced he was in economics and philosophy. -

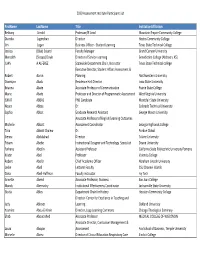

2020 Assessment Institute Participant List Firstname Lastname Title

2020 Assessment Institute Participant List FirstName LastName Title InstitutionAffiliation Bethany Arnold Professor/IE Lead Mountain Empire Community College Diandra Jugmohan Director Hostos Community College Jim Logan Business Officer ‐ Student Learning Texas State Technical College Jessica (Blair) Soland Faculty Manager Grand Canyon University Meredith (Stoops) Doyle Director of Service‐Learning Benedictine College (Atchison, KS) JUAN A ALFEREZ Statewide Department Chair, Instructor Texas State Technical college Executive Director, Student Affairs Assessment & Robert Aaron Planning Northwestern University Osomiyor Abalu Residence Hall Director Iowa State University Brianna Abate Associate Professor of Communication Prairie State College Marie Abate Professor and Director of Programmatic Assessment West Virginia University ISMAT ABBAS PhD Candidate Montclair State University Noura Abbas Dr. Colorado Technical University Sophia Abbot Graduate Research Assistant George Mason University Associate Professor of English/Learning Outcomes Michelle Abbott Assessment Coordinator Georgia Highlands College Talia Abbott Chalew Dr. Purdue Global Sienna Abdulahad Director Tulane University Fitsum Abebe Instructional Designer and Technology Specialist Doane University Farhana Abedin Assistant Professor California State Polytechnic University Pomona Kristin Abel Professor Valencia College Robert Abel Jr Chief Academic Officer Abraham Lincoln University Leslie Abell Lecturer Faculty CSU Channel Islands Dana Abell‐Huffman Faculty instructor Ivy Tech Annette -

Institutional Image: a Case Study of George Mason University

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1989 Institutional image: A case study of George Mason University Elizabeth Anne Acosta-Lewis College of William & Mary - School of Education Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the Higher Education Commons Recommended Citation Acosta-Lewis, Elizabeth Anne, "Institutional image: A case study of George Mason University" (1989). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539618599. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.25774/w4-rd0n-7784 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photo graph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are re produced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

Classical Influences on the United States Constitution from Ancient

John Carroll University Carroll Collected Senior Honors Projects Theses, Essays, and Senior Honors Projects Spring 2015 A Classy Constitution: Classical Influences on the United States Constitution from Ancient Greek and Roman History and Political Thought Shamir Brice John Carroll University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://collected.jcu.edu/honorspapers Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Brice, Shamir, "A Classy Constitution: Classical Influences on the United States Constitution from Ancient Greek and Roman History and Political Thought" (2015). Senior Honors Projects. 85. http://collected.jcu.edu/honorspapers/85 This Honors Paper/Project is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Essays, and Senior Honors Projects at Carroll Collected. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Honors Projects by an authorized administrator of Carroll Collected. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Brice 1 Introduction The Constitution has been the flagship document of United States of America since 1787. After the short reign of the Articles of Confederation, the US Constitution has endured for well over two hundred years. The document that the Founding Fathers drafted in the late eighteenth century has survived after being amended with the Bill of Rights almost immediately after it was ratified by the states.1 The long life of the United States’ governing charter is a testament to the wisdom of the Founding Generation. The Founders were able to craft a constitution that established a system of government that has seen thirteen Atlantic colonies transform into a nation from sea to shining sea. When drafting the Constitution, the Founders are known to have been influenced by European philosophers such as John Locke, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, and the Baron de Montesquieu. -

George Mason University Cloud Computing with IBM

George Mason University Cloud Computing with IBM Problem Named the number one national university to watch in the 2009 rankings of U.S. Provide students with access to professional News and World Report, George Mason University is an innovative, entrepreneurial software and computational environments. institution with global distinction in a wide range of academic fields. Located in Northern Virginia near Washington, D.C., Mason provides students access to Solution diverse cultural experiences and the most sought-after internships and employers Virtual Computing Lab / VCL in the country. Mason offers strong undergraduate and graduate degree programs in engineering and information technology, organizational psychology, health care Goals and visual and performing arts. Mason professors conduct groundbreaking • Increase student access to professional research in areas such as climate change, public policy and the biosciences, mak- and research tools. ing George Mason University a leading example of the modern, public university. • Improve IT response to teaching and learning needs. • Reduce costs associated with delivering The Challenge To become leaders who can address the complex challenges of the 21st century, software as a service. George Mason University students must develop critical skills in acquiring, analyz- Results ing, evaluating, integrating and applying knowledge to generate and develop new ideas and tools. Mason students need tools to learn and then demonstrate • Reduced operating costs research, creativity and critical-thinking in college as well as the workforce upon • Resolved lab administration issues graduation. • Extended access to software • Extended distance education capabilities • Reduced carbon footprint Like all universities, Mason provides students with access to computing services to help them develop these critical skills.