Optical Communications for Small Satellites Ryan W. Kingsbury

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SYLLABUS Optical Fiber Communication

Optical Fiber Communication 10EC72 SYLLABUS Optical Fiber Communication Subject Code : 10EC72 IA Marks : 25 No. of Lecture Hrs/Week : 04 Exam Hours : 03 Total no. of Lecture Hrs. : 52 Exam Marks : 100 PART - A UNIT - 1 OVERVIEW OF OPTICAL FIBER COMMUNICATION: Introduction, Historical development, general system, advantages, disadvantages, and applications of optical fiber communication, optical fiber waveguides, Ray theory, cylindrical fiber (no derivations in article 2.4.4), single mode fiber, cutoff wave length, mode filed diameter. Optical Fibers: fiber materials, photonic crystal, fiber optic cables specialty fibers. 8 Hours UNIT - 2 TRANSMISSION CHARACTERISTICS OF OPTICAL FIBERS: Introduction, Attenuation, absorption, scattering losses, bending loss, dispersion, Intra modal dispersion, Inter modal dispersion. 5 Hours UNIT - 3 OPTICAL SOURCES AND DETECTORS: Introduction, LED’s, LASER diodes, Photo detectors, Photo detector noise, Response time, double hetero junction structure, Photo diodes, comparison of photo detectors. 7 Hours UNIT - 4 FIBER COUPLERS AND CONNECTORS: Introduction, fiber alignment and joint loss, single mode fiber joints, fiber splices, fiber connectors and fiber couplers. 6 Hours Dept of ECE, SJBIT Page 1 Optical Fiber Communication 10EC72 PART - B UNIT - 5 OPTICAL RECEIVER: Introduction, Optical Receiver Operation, receiver sensitivity, quantum limit, eye diagrams, coherent detection, burst mode receiver operation, Analog receivers. 6 Hours UNIT - 6 ANALOG AND DIGITAL LINKS: Analog links – Introduction, overview of analog links, CNR, multichannel transmission techniques, RF over fiber, key link parameters, Radio over fiber links, microwave photonics. Digital links – Introduction, point–to–point links, System considerations, link power budget, resistive budget, short wave length band, transmission distance for single mode fibers, Power penalties, nodal noise and chirping. -

Introduction to Optical Communication Systems

1. Introduction to Optical Communication Systems Optical Communication Systems and Networks Lecture 1: Introduction to Optical Communication Systems 2/ 52 Historical perspective • 1626: Snell dictates the laws of reflection and refraction of light • 1668: Newton studies light as a wave phenomenon – Light waves can be considered as acoustic waves • 1790: C. Chappe “invents” the optical telegraph – It consisted in a system of towers with signaling arms, where each tower acted as a repeater allowing the transmission coded messages over hundred km. – The first Optical telegraph line was put in service between Paris and Lille covering a distance of 200 km. • 1810: Fresnel sets the mathematical basis of wave propagation • 1870: Tyndall demonstrates how a light beam is guided through a falling stream of water • 1830: The optical telegraph is replaced by the electric telegraph, (b/s) until 1866, when the telephony was born • 1873: Maxwell demonstrates that light can be considered as electromagnetic waves http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Claude_Chappe Optical Communication Systems and Networks Lecture 1: Introduction to Optical Communication Systems 3/ 52 Historical perspective • 1800: In Spain, Betancourt builds the first span between Madrid and Aranjuez • 1844: It is published the law for the deployment of the optical telegraphy in Spain – Arms supporting 36 positions, 10º separation Alphabet containing 26 letters and 10 numbers – Spans: Madrid - Irún, 52 towers. Madrid - Cataluña through Valencia, 30 towers. Madrid - Cádiz, 59 towers. • 1855: It is published the law for the deployment of the electrical telegraphy network in Spain • 1880: Graham Bell invents the “photofone” for voice communications TRANSMITTER RECEIVER The transmitter consists of a The receiver is also a mirror made to be vibrated by parabolic reflector in which a the person’s voice, and then selenium cell is placed in its modulating the incident light focus to collect the variations beam towards the receiver. -

Wireless Networks

SUBJECT WIRELESS NETWORKS SESSION 2 WIRELESS Cellular Concepts and Designs" SESSION 2 Wireless A handheld marine radio. Part of a series on Antennas Common types[show] Components[show] Systems[hide] Antenna farm Amateur radio Cellular network Hotspot Municipal wireless network Radio Radio masts and towers Wi-Fi 1 Wireless Safety and regulation[show] Radiation sources / regions[show] Characteristics[show] Techniques[show] V T E Wireless communication is the transfer of information between two or more points that are not connected by an electrical conductor. The most common wireless technologies use radio. With radio waves distances can be short, such as a few meters for television or as far as thousands or even millions of kilometers for deep-space radio communications. It encompasses various types of fixed, mobile, and portable applications, including two-way radios, cellular telephones, personal digital assistants (PDAs), and wireless networking. Other examples of applications of radio wireless technology include GPS units, garage door openers, wireless computer mice,keyboards and headsets, headphones, radio receivers, satellite television, broadcast television and cordless telephones. Somewhat less common methods of achieving wireless communications include the use of other electromagnetic wireless technologies, such as light, magnetic, or electric fields or the use of sound. Contents [hide] 1 Introduction 2 History o 2.1 Photophone o 2.2 Early wireless work o 2.3 Radio 3 Modes o 3.1 Radio o 3.2 Free-space optical o 3.3 -

Cetiie B Tia Nature Red Acted

Probabilistic Methods for Systems Engineering with Application to Nanosatellite Laser Communications by Emily B. Clements Submitted to the Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY June 2018 Massachusetts Institute of Technology 2018. All rights reserved. Autholr Signature redacted (J Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics May 24,2018 Cetiie b tianature red acted Kerri L. Cahoy Associate Professor of Aeronautics and Astronautics red acted Thesis Supervisor Certified by ... Signatu re ........................ David 0. Caplan Senior Staff, MIT Lincoln Laboratory Certified by, S ignature redacted Jeffrey A. Mendenhall Lincoln Laboratory C ignature red acted Senior Staff, MIT Certified by. ................................... David W. Miller Jerome Hunsaker Professor of Aeronauticq and Astronautics Accepted by......... .................. Signature redacted MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE Hamsa Balakrishnan OF TECHNOLOGY Associate Professor of Aeronautics and Astronautics JUN 28 2018 Chair, Graduate Program Committee LIBRARIES ARCHIVES 2 Probabilistic Methods for Systems Engineering with Application to Nanosatellite Laser Communications by Emily B. Clements Submitted to the Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics on May 24, 2018, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Abstract Risk-tolerant platforms such as nanosatellites may be able to accept moderate perfor- mance uncertainty -

Long-Range Free-Space Optical Communication Research Challenges Dr

Long-Range Free-Space Optical Communication Research Challenges Dr. Scott A. Hamilton, MIT Lincoln Laboratory and Prof. Joseph M. Khan, Stanford University The substantial benefits of free-space optical (FSO) or laser communications (lasercom) have been well known to system designers for quite some time, c.f. [1]. The free-space channel, similar to the fiber channel, provides many benefits at optical frequencies compared to radio frequencies (RF) including extremely wide unregulated bandwidth and tightly confined beams (i.e. narrow beam divergence), both of which enable low size, weight and power (SWaP) terminals. However, significant challenges are still perceived: stochastic intensity fluctuations in a received optical signal after propagating through the atmosphere, power-starved link mode of operation, and narrow transmit beams that must be precisely pointed and tracked. Since the late 1970’s the United States [2], Europe [3] and Japan [4] have actively been developing FSO technology motivated primarily for long-haul spaceborne communication systems. While early efforts were focused on maturing FSO technology, the past decade has seen significant progress toward demonstrating the practicality of FSO for multiple applications. The first high-rate demonstration of FSO between a satellite in Geosynchronous (GEO) orbit and the ground was achieved by the US during the GeoLITE experiment in 2001. A short time later, the European Space Agency (ESA) demonstrated a 50- Mbps FSO link operating at 800-nm wavelengths between their Artemis GEO satellite and: i) another ESA spacecraft in Low-Earth orbit (LEO) in 2001 [5]; ii) a ground station located in Tenerife, Spain in 2001 [6]; and iii) an airplane flying at altitudes as low as 6,000 meters outfitted with an FSO terminal developed by France’s Astrium EADS in 2006 [7]. -

High Frequency Communications – an Introductory Overview

High Frequency Communications – An Introductory Overview - Who, What, and Why? 13 August, 2012 Abstract: Over the past 60+ years the use and interest in the High Frequency (HF -> covers 1.8 – 30 MHz) band as a means to provide reliable global communications has come and gone based on the wide availability of the Internet, SATCOM communications, as well as various physical factors that impact HF propagation. As such, many people have forgotten that the HF band can be used to support point to point or even networked connectivity over 10’s to 1000’s of miles using a minimal set of infrastructure. This presentation provides a brief overview of HF, HF Communications, introduces its primary capabilities and potential applications, discusses tools which can be used to predict HF system performance, discusses key challenges when implementing HF systems, introduces Automatic Link Establishment (ALE) as a means of automating many HF systems, and lastly, where HF standards and capabilities are headed. Course Level: Entry Level with some medium complexity topics Agenda • HF Communications – Quick Summary • How does HF Propagation work? • HF - Who uses it? • HF Comms Standards – ALE and Others • HF Equipment - Who Makes it? • HF Comms System Design Considerations – General HF Radio System Block Diagram – HF Noise and Link Budgets – HF Propagation Prediction Tools – HF Antennas • Communications and Other Problems with HF Solutions • Summary and Conclusion • I‟d like to learn more = “Critical Point” 15-Aug-12 I Love HF, just about On the other hand… anybody can operate it! ? ? ? ? 15-Aug-12 HF Communications – Quick pretest • How does HF Communications work? a. -

Chapter 5 the Microstrip Antenna

CHAPTER 5 THE MICROSTRIP ANTENNA 5.1 Introduction Applications that require low-profile, light weight, easily manufactured, inexpensive, conformable antennas often use some form of a microstrip radiator. The microstrip antenna (MSA) is a resonant structure that consists of a dielectric substrate sandwiched between a metallic conducting patch and a ground plane. The MSA is commonly excited using a microstrip edge feed or a coaxial probe. The canonical forms of the MSA are the rectangular and circular patch MSAs. The rectangular patch antenna in Figure 5.1 is fed using a microstrip edge feed and the circular patch antenna is fed using a coaxial probe. (a) (b) Coaxial Feed Microstrip Feed Figure 5.1. (a) A rectangular patch microstrip antenna fed with a microstrip edge feed. (b) A circular patch microstrip antenna fed with a coaxial probe feed. The patch shapes in Figure 5.1 are symmetric and their radiation is easy to model. However, application specific patch shapes are often used to optimize certain aspects of MSA performance. 154 The earliest work on the MSA was performed in the 1950s by Gutton and Baissinot in France and Deschamps in the United States. [1] Demand for low-profile antennas increased in the 1970s, and interest in the MSA was renewed. Notably, Munson obtained the original patent on the MSA, and Howell published the first experimental data involving circular and rectangular patch MSA characteristics. [1] Today the MSA is widely used in practice due to its low profile, light weight, cheap manufacturing costs, and potential conformability. [2] A number of methods are used to model the performance of the MSA. -

Optical Communications and Networks - Review and Evolution (OPTI 500)

Optical Communications and Networks - Review and Evolution (OPTI 500) Massoud Karbassian [email protected] Contents Optical Communications: Review Optical Communications and Photonics Why Photonics? Basic Knowledge Optical Communications Characteristics How Fibre-Optic Works? Applications of Photonics Optical Communications: System Approach Optical Sources Optical Modulators Optical Receivers Modulations Optical Networking: Review Core Networks: SONET, PON Access Networks Optical Networking: Evolution Summary 2 Optical Communications and Photonics Photonics is the science of generating, controlling, processing photons. Optical Communications is the way of interacting with photons to deliver the information. The term ‘Photonics’ first appeared in late 60’s 3 Why Photonics? Lowest Attenuation Attenuation in the optical fibre is much smaller than electrical attenuation in any cable at useful modulation frequencies Much greater distances are possible without repeaters This attenuation is independent of bit-rate Highest Bandwidth (broadband) High-speed The higher bandwidth The richer contents Upgradability Optical communication systems can be upgraded to higher bandwidth, more wavelengths by replacing only the transmitters and receivers Low Cost For fibres and maintenance 4 Fibre-Optic as a Medium Core and Cladding are glass with appropriate optical properties!!! Buffer is plastic for mechanical protection 5 How Fibre-Optic Works? Snell’s Law: n1 Sin Φ1 = n2 Sin Φ2 6 Fibre-Optics Fibre-optic cable functions -

Free Space Optics Vs Radio Frequency Wireless Communication

I.J. Information Technology and Computer Science, 2016, 9, 1-8 Published Online September 2016 in MECS (http://www.mecs-press.org/) DOI: 10.5815/ijitcs.2016.09.01 Free Space Optics Vs Radio Frequency Wireless Communication Rayan A. Alsemmeari and Sheikh Tahir Bakhsh Faculty of Computing and Information Technology, King Abdulaziz University, Saudi Arabia E-mail: {ralsemmeari, stbakhsh}@kau.edu.sa Hani Alsemmeari Institute of Public Administration Information and Technology department E-mail: [email protected] Abstract—This paper presents the free space optics (FSO) but on very low data rates. Laser technology enhanced and radio frequency (RF) wireless communication. The the use of free space optics and is now highly dependent paper explains the feature of FSO and compares it with on the laser technology. FSO in original form was the already deployed technology of RF communication in developed by the NASA and used for the military terms of data rate, efficiency, capacity and limitations. purposes in different era as fast communication link. The The data security is also discussed in the paper for technology has many commonalities with the fiber optics identification of the system to be able to use in normal technology but behaves differently in the field due to the circumstances. These systems are also discussed in a way method of transmission for both the technologies [5, 6]. that they could efficiently combine to form the single RF technology is very old technology for system with greater throughput and higher reliability. communication. It is the wireless technology for data communication. It is considered to be in use for more Index Terms—Free Space Optics, Radio frequency, than 100 years. -

Monitoring Times 2000 INDEX

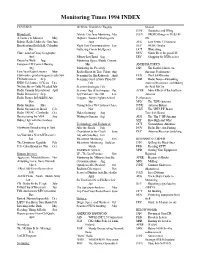

Monitoring Times 1994 INDEX FEATURES: Air Show: Triumph to Tragedy Season Aug JUNE Duopolies and DXing Broadcast: Atlantic City Aero Monitoring May JULY TROPO Brings in TV & FM A Journey to Morocco May Dayton's Aviation Extravaganza DX Bolivia: Radio Under the Gun June June AUG Low Power TV Stations Broadcasting Battlefield, Colombia Flight Test Communications Jan SEP WOW, Omaha Dec Gathering Comm Intelligence OCT Winterizing Chile: Land of Crazy Geography June NOV Notch filters for good DX April Military Low Band Sep DEC Shopping for DX Receiver Deutsche Welle Aug Monitoring Space Shuttle Comms European DX Council Meeting Mar ANTENNA TOPICS Aug Monitoring the Prez July JAN The Earth’s Effects on First Year Radio Listener May Radio Shows its True Colors Aug Antenna Performance Flavoradio - good emergency radio Nov Scanning the Big Railroads April FEB The Half-Rhombic FM SubCarriers Sep Scanning Garden State Pkwy,NJ MAR Radio Noise—Debunking KNLS Celebrates 10 Years Dec Feb AntennaResonance and Making No Satellite or Cable Needed July Scanner Strategies Feb the Real McCoy Radio Canada International April Scanner Tips & Techniques Dec APRIL More Effects of the Earth on Radio Democracy Sep Spy Catchers: The FBI Jan Antenna Radio France Int'l/ALLISS Ant Topgun - Navy's Fighter School Performance Nov Mar MAY The T2FD Antenna Radio Gambia May Tuning In to a US Customs Chase JUNE Antenna Baluns Radio Nacional do Brasil Feb Nov JULY The VHF/UHF Beam Radio UNTAC - Cambodia Oct Video Scanning Aug Traveler's Beam Restructuring the VOA Sep Waiting -

Comparative Study of Optical and RF Communication Systems H

I . , , comparative study of optical and RF Communication Systems for a MrJrs Mission H. Hernmati, K. Wilson, M. Sue, D. Rascoe, F. Lansing, h4. Wilhelm, L. Harcke, and C. Chen Jet Propulsion Laboratory California Institute of Technology Pasadena, CA 91109 AIISTRACT We luwc performed a study on tclcconmnmication sj’s[cnrs for a hypothetical mission to Mars. The objcctivc cf t hc study was to evaluate and compare lhc bcncfils that .rnicrowavc. (X-band. and Ka-band) and Optical conmumications $clmo]ogi$s afford to future missions. TIE lclcconmwnicatio]; systems were required to return data ‘atlcr launch and in-ohit at 2.7 AU with daily data volumes of 0.1, 1, or 10 Gbits. Space-borne tcnnimls capable of delivering each of the three data rates WCJC proposed and charactcnmd in terms of mass, power consumption, sire, and cost. The estimated panwnctcw for X- band, Ka-band, and Optical frcqucncics arc compared and presented here. For data volumes of 0.1 and 1 Gigs-bit pcr day, the X-band downlink system has a mass 1.5 times that of Ka-band, and 2.5 times that of Optical systcm. Ka-band oftcrcd about 20% power saving at 10 Gbit/day over X-band. For all data volumes, the optical communication terminals were lower in mass than the RF terminals. For data volumes of 1 and 10 Gb/day, the space-borne optical terminal also had a lower required DC power. ln all three cases, optical communications had a slightly higher development cost for the space tcnninal, 1. 1NTI{OD[JCTION The deep space cxTloration program has been steadily increasing the frequcncic$ used for planctmy radio communication since the inception of NASA in 1957. -

Low-Profile Wideband Antennas Based on Tightly Coupled Dipole

Low-Profile Wideband Antennas Based on Tightly Coupled Dipole and Patch Elements Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Erdinc Irci, B.S., M.S. Graduate Program in Electrical and Computer Engineering The Ohio State University 2011 Dissertation Committee: John L. Volakis, Advisor Kubilay Sertel, Co-advisor Robert J. Burkholder Fernando L. Teixeira c Copyright by Erdinc Irci 2011 Abstract There is strong interest to combine many antenna functionalities within a single, wideband aperture. However, size restrictions and conformal installation requirements are major obstacles to this goal (in terms of gain and bandwidth). Of particular importance is bandwidth; which, as is well known, decreases when the antenna is placed closer to the ground plane. Hence, recent efforts on EBG and AMC ground planes were aimed at mitigating this deterioration for low-profile antennas. In this dissertation, we propose a new class of tightly coupled arrays (TCAs) which exhibit substantially broader bandwidth than a single patch antenna of the same size. The enhancement is due to the cancellation of the ground plane inductance by the capacitance of the TCA aperture. This concept of reactive impedance cancellation was motivated by the ultrawideband (UWB) current sheet array (CSA) introduced by Munk in 2003. We demonstrate that as broad as 7:1 UWB operation can be achieved for an aperture as thin as λ/17 at the lowest frequency. This is a 40% larger wideband performance and 35% thinner profile as compared to the CSA. Much of the dissertation’s focus is on adapting the conformal TCA concept to small and very low-profile finite arrays.