African American Old-Time String Band Music: a Selective Discography

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Folk Music in the Melting Pot” at the Sheldon Concert Hall

Education Program Handbook for Teachers WELCOME We look forward to welcoming you and your students to the Sheldon Concert Hall for one of our Education Programs. We hope that the perfect acoustics and intimacy of the hall will make this an important and memorable experience. ARRIVAL AND PARKING We urge you to arrive at The Sheldon Concert Hall 15 to 30 minutes prior to the program. This will allow you to be seated in time for the performance and will allow a little extra time in case you encounter traffic on the way. Seating will be on a first come-first serve basis as schools arrive. To accommodate school schedules, we will start on time. The Sheldon is located at 3648 Washington Boulevard, just around the corner from the Fox Theatre. Parking is free for school buses and cars and will be available on Washington near The Sheldon. Please enter by the steps leading up to the concert hall front door. If you have a disabled student, please call The Sheldon (314-533-9900) to make arrangement to use our street level entrance and elevator to the concert hall. CONCERT MANNERS Please coach your students on good concert manners before coming to The Sheldon Concert Hall. Good audiences love to listen to music and they love to show their appreciation with applause, usually at the end of an entire piece and occasionally after a good solo by one of the musicians. Urge your students to take in and enjoy the great music being performed. Food and drink are prohibited in The Sheldon Concert Hall. -

WORKSHOP: Around the World in 30 Instruments Educator’S Guide [email protected]

WORKSHOP: Around The World In 30 Instruments Educator’s Guide www.4shillingsshort.com [email protected] AROUND THE WORLD IN 30 INSTRUMENTS A MULTI-CULTURAL EDUCATIONAL CONCERT for ALL AGES Four Shillings Short are the husband-wife duo of Aodh Og O’Tuama, from Cork, Ireland and Christy Martin, from San Diego, California. We have been touring in the United States and Ireland since 1997. We are multi-instrumentalists and vocalists who play a variety of musical styles on over 30 instruments from around the World. Around the World in 30 Instruments is a multi-cultural educational concert presenting Traditional music from Ireland, Scotland, England, Medieval & Renaissance Europe, the Americas and India on a variety of musical instruments including hammered & mountain dulcimer, mandolin, mandola, bouzouki, Medieval and Renaissance woodwinds, recorders, tinwhistles, banjo, North Indian Sitar, Medieval Psaltery, the Andean Charango, Irish Bodhran, African Doumbek, Spoons and vocals. Our program lasts 1 to 2 hours and is tailored to fit the audience and specific music educational curriculum where appropriate. We have performed for libraries, schools & museums all around the country and have presented in individual classrooms, full school assemblies, auditoriums and community rooms as well as smaller more intimate settings. During the program we introduce each instrument, talk about its history, introduce musical concepts and follow with a demonstration in the form of a song or an instrumental piece. Our main objective is to create an opportunity to expand people’s understanding of music through direct expe- rience of traditional folk and world music. ABOUT THE MUSICIANS: Aodh Og O’Tuama grew up in a family of poets, musicians and writers. -

Unit Title: It's About Time – the Power of Folk Music

Colorado Teacher-Authored Instructional Unit Sample Music 7th Grade Unit Title: It’s About Time – The Power of Folk Music Non-Ensemble Based INSTRUCTIONAL UNIT AUTHORS Denver Public Schools Regina Dunda Metro State University of Denver Carla Aguilar, PhD BASED ON A CURRICULUM OVERVIEW SAMPLE AUTHORED BY Falcon School District Harriet G. Jarmon, PhD Center School District Kate Newmeyer Colorado’s District Sample Curriculum Project This unit was authored by a team of Colorado educators. The template provided one example of unit design that enabled teacher- authors to organize possible learning experiences, resources, differentiation, and assessments. The unit is intended to support teachers, schools, and districts as they make their own local decisions around the best instructional plans and practices for all students. DATE POSTED: MARCH 31, 2014 Colorado Teacher-Authored Sample Instructional Unit Content Area Music Grade Level 7th Grade Course Name/Course Code General Music (Non-Ensemble Based) Standard Grade Level Expectations (GLE) GLE Code 1. Expression of Music 1. Perform music in three or more parts accurately and expressively at a minimal level of level 1 to 2 on the MU09-GR.7-S.1-GLE.1 difficulty rating scale 2. Perform music accurately and expressively at the minimal difficulty level of 1 on the difficulty rating scale at MU09-GR.7-S.1-GLE.2 the first reading individually and as an ensemble member 3. Demonstrate understanding of modalities MU09-GR.7-S.1-GLE.3 2. Creation of Music 1. Sequence four to eight measures of music melodically and rhythmically MU09-GR.7-S.2-GLE.1 2. -

Traditional Irish Music Presentation

Traditional Irish Music Topics Covered: 1. Traditional Irish Music Instruments 2 Traditional Irish tunes 3. Music notation & Theory Related to Traditional Irish Music Trad Irish Instruments ● Fiddle ● Bodhrán ● Irish Flute ● Button Accordian ● Tin/Penny Whistle ● Guitar ● Uilleann Pipes ● Mandolin ● Harp ● Bouzouki Fiddle ● A fiddle is the same as a violin. For Irish music, it is tuned the same, low to high string: G, D, A, E. ● The medieval fiddle originated in Europe in ● The term “fiddle” is used the 10th century, which when referring to was relatively square traditional or folk music. shaped and held in the ● The fiddle is one of the arms. primarily used instruments for traditional Irish music and has been used for over 200 years in Ireland. Fiddle (cont.) ● The violin in its current form was first created in the early 16th century (early 1500s) in Northern Italy. ● When fiddlers play traditional Irish music, they ornament the music with slides, cuts (upper grace note), taps (lower grace note), rolls, drones (also known as a double stop), accents, staccato and sometimes trills. ● Irish fiddlers tend to make little use of vibrato, except for slow airs and waltzes, which is also used sparingly. Irish Flute ● Flutes have been played in Ireland for over a thousand years. ● There are two types of flutes: Irish flute and classical flute. ● Irish flute is typically used ● This flute originated when playing Irish music. in England by flautist ● Irish flutes are made of wood Charles Nicholson and have a conical bore, for concert players, giving it an airy tone that is but was adapted by softer than classical flute and Irish flautists as tin whistle. -

Music Tech-1

Radnor Middle School Course Overview Music Technology I. Course Description Music Technology is offered as an eighth grade music elective, meeting three times a cycle. Students will be introduced to the study of music technology and music fundamentals. Areas of instruction will include instrument and equipment care, beginning level music literacy (reading and writing music), keyboard performance skills, music technology related history, concepts, terminology and experience with a variety of applications. II. Resources, Materials , Equipment • iMacs • GarageBand • Korg K61p MIDI Studio Contoller Keyboards • Student Journals III. Course Goals, Objectives (Essential Questions, Enduring Understandings) Students will be able to: 1. Accurately perform melody, harmony and rhythm parts of a composition and record the parts separately into the sequencer of the keyboard. 2. Accurately perform melody, harmony and rhythm parts of their own composition and record the parts separately into the sequencer of the keyboard. 3. Record multiple parts to an electronic “sound piece” using non-traditional instrument timbres and effects. 4. Orchestrate and perform three- and four-part synthesizer ensemble pieces within expected performance parameters for their individual levels of expertise. 5. Transfer sequenced MIDI files from the keyboard disk into the computer and, using appropriate software, edit needed corrections, format, and print out the composition. 6. Change instrumentation using an existing music composition stored as MIDI data; and alter tempo, range, and dynamics during the course of the piece, while still maintaining the original integrity of the composition. 7. Compose a four-part electronic sound piece using varied timbre (tone), texture, and dynamics of at least three minute length. Students may incorporate digitally recorded audio sounds into this piece. -

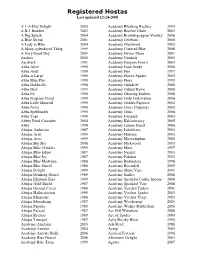

Registered Hostas Last Updated 12-24-2008

Registered Hostas Last updated 12-24-2008 A 1-A-Day Delight 2003 Academy Blushing Recluse 1999 A B-1 Bomber 2002 Academy Bonfire Glade 2003 A Big Splash 2004 Academy Brobdingnagian Viridity 2006 A Blue Streak 2001 Academy Celeborn 2000 A Lady in Blue 2004 Academy Chetwood 2005 A Many-splendored Thing 1999 Academy Cratered Blue 2008 A Very Good Boy 2005 Academy Devon Moor 2001 Aachen 2005 Academy Dimholt 2005 Aardvark 1991 Academy Fangorn Forest 2003 Abba Alive 1990 Academy Faux Sedge 2008 Abba Aloft 1990 Academy Fire 1997 Abba at Large 1990 Academy Flaxen Spades 2002 Abba Blue Plus 1990 Academy Flora 1999 Abba Dabba Do 1998 Academy Galadriel 2000 Abba Dew 1999 Academy Gilded Dawn 2008 Abba Fit 1990 Academy Glowing Embers 2008 Abba Fragrant Cloud 1990 Academy Gold Codswallop 2006 Abba Little Showoff 1990 Academy Golden Papoose 2004 Abba Nova 1990 Academy Grass Clippings 2005 Abba Spellbinder 1990 Academy Grins 2008 Abba Tops 1990 Academy Isengard 2003 Abbey Pond Cascades 2004 Academy Kakistocracy 2005 Abby 1990 Academy Lemon Knoll 2006 Abiqua Ambrosia 1987 Academy Lothlórien 2004 Abiqua Ariel 1999 Academy Mallorn 2003 Abiqua Aries 1999 Academy Mavrodaphne 2000 Abiqua Big Sky 2008 Academy Mirkwood 2003 Abiqua Blue Crinkles 1999 Academy Muse 1997 Abiqua Blue Edger 1987 Academy Nazgul 2003 Abiqua Blue Jay 1987 Academy Palantir 2003 Abiqua Blue Madonna 1988 Academy Redundant 1998 Abiqua Blue Shield 1988 Academy Rivendell 2005 Abiqua Delight 1999 Academy Shiny Vase 2001 Abiqua Drinking Gourd 1989 Academy Smiles 2008 Abiqua Elephant Ears 1999 -

The Open Back of the Open-Back Banjo

HDP: 13 { 02 glasswork by M. Desy The Open Back of the Open-Back Banjo David Politzer∗ California Institute of Technology (Dated: December 2, 2013) ...in which a simple question turned into a great adventure and even got answered. (Of course, you might already know the answer yourself.) In a triumph of elementary physics, six measured numbers receive a satisfactory account using two adjustable parameters. ∗[email protected]; http://www.its.caltech.edu/~politzer; 452-48 Caltech, Pasadena CA 91125 2 The Open Back of the Open-Back Banjo I. THE RIM QUESTION The question seemed straightforward. What is the impact of rim height on the sound of an open-back banjo? FIG. 1. an open-back banjo's open back 3 mylar (or skin) head metal flange rim height drum rim wall open back resonator back (Which head is bigger? Auditory (as opposed to optical) illusions only came into their own with the development of digital sound.) FIG. 2. schematic banjo pot cross sections There are a great many choices in banjo design, construction, and set-up. For almost all of them, there is consensus among players and builders on the qualitative effect of possible choices. Just a few of the many are: string material and gauge; drum head material, thickness, and tension; neck wood and design; rim material and weight; tailpiece design and height; tone ring design and material. However, there is no universal ideal of banjo perfection. Virtually every design that has ever existed is still played with gusto, and new ones of those designs are still in production. -

Scottish and Irish Elements of Appalachian Fiddle Music

Butler University Digital Commons @ Butler University Undergraduate Honors Thesis Collection Undergraduate Scholarship 3-1995 Scottish and Irish Elements of Appalachian Fiddle Music Matthew S. Emmick Butler University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/ugtheses Part of the Ethnomusicology Commons, and the Musicology Commons Recommended Citation Emmick, Matthew S., "Scottish and Irish Elements of Appalachian Fiddle Music" (1995). Undergraduate Honors Thesis Collection. 21. https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/ugtheses/21 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Scholarship at Digital Commons @ Butler University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Thesis Collection by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Butler University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BUTLER UNIVERSITY HONORS PROGRAM Honors Thesis Certification Matthew S. Emmick Applicant (Name as It Is to appear on dtplomo) Scottish and Irish Elements of Appalachian Fiddle M'-Isic Thesis title _ May, 1995 lnter'lded date of commencemenf _ Read and approved by: ' -4~, <~ /~.~~ Thesis adviser(s)/ /,J _ 3-,;13- [.> Date / / - ( /'--/----- --",,-..- Commltte~ ;'h~"'h=j.R C~.16b Honors t-,\- t'- ~/ Flrst~ ~ Date Second Reader Date Accepied and certified: JU).adr/tJ, _ 2111c<vt) Director DiJe For Honors Program use: Level of Honors conferred: University Magna Cum Laude Departmental Honors in Music and High Honors in Spanish Scottish and Irish Elements of Appalachian Fiddle Music A Thesis Presented to the Departmt!nt of Music Jordan College of Fine Arts and The Committee on Honors Butler University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation Honors Matthew S. Emmick March, 24, 1995 -l _ -- -"-".,---. -

1 B.O.M.Newsletter #331Web 今年の IBMA・WOB ツアー 今月の新入荷

B.O.M.Newsletter #331web なるシエラ・ハルのツアーをサポートしてください。 お願いします!! 2008 年 5 月 9 日 ▼ 25 年目を迎えているムーンシャイナー誌です!! ▼今月のニュースレターはウエブサイトのみです。紙刷 月刊ムーンシャイナー定期購読は1年間(1 2 冊) り版ご希望の方はお申し出下さい。 ¥6,000- 半年間(6冊)¥3,300-。購読開始希望月を お知らせいただければ、振り込み票とともに早速お送 ▼恒例の「宝塚春フェス」は、いつもの三田アスレチッ りします。…定期購読を、是非ともよろしく!! ク(0795-69-0024)で、5 月 31 日(土)3 時から 6 月 1 日 最新 5 月号(MS-2507 ¥525-)は来日のクリス・ヒ (日)のお昼頃まで、新緑の山中、野外で開催します(雨 ルマンとハーブ・ぺダースンを表紙特集に、カリフォ 天の場合は屋内)。コンサートは午後 6 時から、現地書き ルニア・ブルーグラス考、ペティブーカ『TOKYO 込み式でプログラムを作成します。梅雨入り前の一日、 Bluegrass Honeys』、マイク伊藤『音楽から見えるア キャンプをしながら森林浴や「焚き火ジャム」で英気を メリカ』、ゲティスバーグ・ブルーグラス・フェス、 養いませんか?参加費用 ¥2,500- ディープサウス・ピッキンパーティ、日本ブルーグラ なお、宿泊(バンガローや民宿)をご希望の方は直接、 ス年表⑰「1964-65 年」、中西孝仁の IBMA2007 リポー 三田アスレチックにお問い合わせください。 トほか、日米ブルーグラス情報満載。 ちなみに、夏フェスは7月 31 日から8月3日!! ▼今月、またまたすごい天才マンドリン少女が全米デ 今年の IBMA・WOB ツアー ビュー。すでに米国では数年前から大きな話題となり、 今年もナッシュビルのダウンタウンど真ん中、高層 ラウンダーが 13 歳で契約、3年の時間をかけ、満を持し ホ テルを中心に開かれる IBMA ワールド・オブ・ブルー てのデビューです。そのシエラ・ハル、今年7月に来日 グラス(WOB)へのツアーがあります。基本は 9 月 29 が決まりました。 日出発 10 月 6 日帰国で準備中、また WOB 期間全参加 IBMA(国際ブルーグラス音楽協会)の肝いりで、ケン やその前後のご相談もお受けしています。お気軽にお タッキーとウエスト・バージニア、そしてテネシーから 問い合わせください。なお、8月 29 日が応 募締め切 高校生のブルーグラス3バンド、総勢 16 名のブルーグラ りです。 ス・キッズのリーダー格として埼玉県の川口総合文化セ ンターの国際交流フェスに参加することになりました。 今月の新入荷注目作品 また交流フェス期間のホームステイの後、米国から現在 ROU-0601 SIERRA HULL『Secret』 の正式メンバーを呼び寄せ、シエラ・ハル&ハイウェイ CD¥2,573-(本体 ¥2,450-) 111 として7月 29 日から 10 日間、全国をツアーします。 満を持して発表した 16 歳の天才マンドリン少女、シ 彼女ら自身も、IBMA も、そして日本の受け入れ側も、 エラ・ハルの全米デビュー作。7月来日だぞ!! まっ 全国ツアーにボランティアとして協力し、現在もっとも すぐなブルーグラスと信じ難いテク、物凄い作品、… 旬なアーティストを見ていただこうという趣旨です。全 驚きますよ。ブルーグラス新入荷参照。 国のブルーグラス/オールドタイム/カントリー・ファ RHY-325 MASHVILLE BRIGADE ンの皆さん、間違いなく近い将来、とんでもない大物に -

2O21-22 Season

CELEBRATING 2O21-22 SEASON EST. 1996 2021-22 contents 5 Welcome 6 Season Calendar 8 Subscribe 10 Series 22 Performances 86 Performances for Young People 88 How to Order 89 Discounts 91 Helpful Information 92 Beyond the Footlights 94 Support On the cover: Hodgson Concert Hall 2Camerata RCO Painting: J.N. Smith 3 Welcome Back What a time it has been! Our world has experienced unprecedented disruption since we last gathered in the spring of 2020 in our beautiful venues to witness exquisite music, dance, and theatre together. Throughout these many long and painful months of separation and isolation, I have been yearning for the time when we can be together once again. It appears that time is finally now upon us! I am absolutely thrilled to share our plans for celebrating the University of Georgia Performing Arts Center’s historic 25th anniversary season throughout the fall of 2021 and spring of 2022. Our silver anniversary season will feature a variety of acclaimed guest artists—some new to us and some returning favorites—with an equally wide variety of personal life experiences. They will come to us from across the United States and several different countries. Their experiences inform their work, and we will, for a brief moment in time, commune together as the universal languages of music, spoken word, and movement unite us in hope and healing. Not only has the world changed significantly since we first opened our doors 25 years ago, it has changed dramatically in the last year as we have endured the devastating impact of a global pandemic, social injustice, political uncertainty, and any number of other things. -

AFM Course Curriculum

AMERICAN FIDDLE METHOD COURSE Curriculum Index GETTING READY Lesson 1 Introduction to AFM Lesson 2 Gear you need Lesson 3 Parts of a fiddle Lesson 4 Parts of a bow Lesson 5 Checking your fiddle’s setup Lesson 6 Checking your bow’s setup Lesson 7 Care of your instrument Lesson 8 Fitting a shoulder rest Lesson 9 Rosining the bow Lesson 10 Tuning using the pegs Lesson 11 Tuning using the fine tuners Lesson 12 Applying tapes to the fingerboard Lesson 13 Names of the notes STRATEGIES FOR SUCCESS Lesson 1 Three lists Lesson 2 Anatomy of a fiddle tune Lesson 3 Learning by ear Lesson 4 Small Overlapping Phases –SOPS Lesson 5 Muscle memory Lesson 6 Using a metronome LEVEL I Violin Position Lesson 1 Natural body position Lesson 2 Positioning the fiddle Lesson 3 Position of the left arm and hand st Lesson 4 Thumb and “Mirror 1 Finger” Beginning Bowing Lesson 5 Holding the bow Lesson 6 Principles of bowing Lesson 7 Bowing continuums Lesson 8 Diagnosing your tone Lesson 9 Bowing string changes Lesson 10 Beginning rhythms Beginning Fingering Lesson 11 A string – 1st finger Lesson 12 A string – 2nd finger Lesson 13 A string – 3rd finger Lesson 14 A string – three fingers Lesson 15 A string – practice Lesson 16 D string – three fingers Lesson 17 D string – practice Lesson 18 G string – three fingers Lesson 19 G string – practice Lesson 20 E string – three fingers Lesson 21 E string – practice Scales Lesson 22 How to play in tune Lesson 23 D Scale Lesson 24 G Scale Lesson 25 A Scale Lesson 26 Twinkle –key of D Lesson 27 Twinkle –key of A Lesson 28 Twinkle –key of -

Acoustic Guitar Songs by Title 11Th Street Waltz Sean Mcgowan Sean

Acoustic Guitar Songs by Title Title Creator(s) Arranger Performer Month Year 101 South Peter Finger Peter Finger Mar 2000 11th Street Waltz Sean McGowan Sean McGowan Aug 2012 1952 Vincent Black Lightning Richard Thompson Richard Thompson Nov/Dec 1993 39 Brian May Queen May 2015 50 Ways to Leave Your Lover Paul Simon Paul Simon Jan 2019 500 Miles Traditional Mar/Apr 1992 5927 California Street Teja Gerken Jan 2013 A Blacksmith Courted Me Traditional Martin Simpson Martin Simpson May 2004 A Daughter in Denver Tom Paxton Tom Paxton Aug 2017 A Day at the Races Preston Reed Preston Reed Jul/Aug 1992 A Grandmother's Wish Keola Beamer, Auntie Alice Namakelua Keola Beamer Sep 2001 A Hard Rain's A-Gonna Fall Bob Dylan Bob Dylan Dec 2000 A Little Love, A Little Kiss Adrian Ross, Lao Silesu Eddie Lang Apr 2018 A Natural Man Jack Williams Jack Williams Mar 2017 A Night in Frontenac Beppe Gambetta Beppe Gambetta Jun 2004 A Tribute to Peador O'Donnell Donal Lunny Jerry Douglas Sep 1998 A Whiter Shade of Pale Keith Reed, Gary Brooker Martin Tallstrom Procul Harum Jun 2011 About a Girl Kurt Cobain Nirvana Nov 2009 Act Naturally Vonie Morrison, Johnny Russel The Beatles Nov 2011 Addison's Walk (excerpts) Phil Keaggy Phil Keaggy May/Jun 1992 Adelita Francisco Tarrega Sep 2018 Africa David Paich, Jeff Porcaro Andy McKee Andy McKee Nov 2009 After the Rain Chuck Prophet, Kurt Lipschutz Chuck Prophet Sep 2003 After You've Gone Henry Creamer, Turner Layton Sep 2005 Ain't It Enough Ketch Secor, Willie Watson Old Crow Medicine Show Jan 2013 Ain't Life a Brook