Livent Fraud JFC.Pdf (158.7Kb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Christopher Plummer

Christopher Plummer "An actor should be a mystery," Christopher Plummer Introduction ........................................................................................ 3 Biography ................................................................................................................................. 4 Christopher Plummer and Elaine Taylor ............................................................................. 18 Christopher Plummer quotes ............................................................................................... 20 Filmography ........................................................................................................................... 32 Theatre .................................................................................................................................... 72 Christopher Plummer playing Shakespeare ....................................................................... 84 Awards and Honors ............................................................................................................... 95 Christopher Plummer Introduction Christopher Plummer, CC (born December 13, 1929) is a Canadian theatre, film and television actor and writer of his memoir In "Spite of Myself" (2008) In a career that spans over five decades and includes substantial roles in film, television, and theatre, Plummer is perhaps best known for the role of Captain Georg von Trapp in The Sound of Music. His most recent film roles include the Disney–Pixar 2009 film Up as Charles Muntz, -

The Enduring Power of Musical Theatre Curated by Thom Allison

THE ENDURING POWER OF MUSICAL THEATRE CURATED BY THOM ALLISON PRODUCTION SUPPORT IS GENEROUSLY PROVIDED BY NONA MACDONALD HEASLIP PRODUCTION CO-SPONSOR LAND ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Welcome to the Stratford Festival. It is a great privilege to gather and share stories on this beautiful territory, which has been the site of human activity — and therefore storytelling — for many thousands of years. We wish to honour the ancestral guardians of this land and its waterways: the Anishinaabe, the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, the Wendat, and the Attiwonderonk. Today many Indigenous peoples continue to call this land home and act as its stewards, and this responsibility extends to all peoples, to share and care for this land for generations to come. CURATED AND DIRECTED BY THOM ALLISON THE SINGERS ALANA HIBBERT GABRIELLE JONES EVANGELIA KAMBITES MARK UHRE THE BAND CONDUCTOR, KEYBOARD ACOUSTIC BASS, ELECTRIC BASS, LAURA BURTON ORCHESTRA SUPERVISOR MICHAEL McCLENNAN CELLO, ACOUSTIC GUITAR, ELECTRIC GUITAR DRUM KIT GEORGE MEANWELL DAVID CAMPION The videotaping or other video or audio recording of this production is strictly prohibited. A MESSAGE FROM OUR ARTISTIC DIRECTOR WORLDS WITHOUT WALLS Two young people are in love. They’re next- cocoon, and now it’s time to emerge in a door neighbours, but their families don’t get blaze of new colour, with lively, searching on. So they’re not allowed to meet: all they work that deals with profound questions and can do is whisper sweet nothings to each prompts us to think and see in new ways. other through a small gap in the garden wall between them. Eventually, they plan to While I do intend to program in future run off together – but on the night of their seasons all the plays we’d planned to elopement, a terrible accident of fate impels present in 2020, I also know we can’t just them both to take their own lives. -

333 Bay Street, Suite 2400 Toronto, Ontario, Canada

EMERSON ADVISORY 333 BAY STREET, SUITE 2400 BAY ADELAIDE CENTRE, BOX 20 TORONTO, ONTARIO, CANADA M5H 2T6 H. GARFIELD EMERSON, Q.C. DIRECT: 416-865-4350 PRINCIPAL FAX: 416-364-7813 CELL: 416-303-4300 [email protected] [email protected] 17th December 2013 ETHICAL LEADERSHIP AND CORRUPT PRACTICES “I am the master of my fate I am the captain of my soul.” William Ernest Henley, “Invictus” Character Trumps Everything - The Imperative of Morale Leadership Corporations and other entities do not function as automatons, mechanically driven by an engine or installed silicon computer chip deciding their actions. Every act of a corporation is determined and undertaken by a human. People, not companies, make decisions. The values and underlying principles that individuals have determine how they assess issues, respond to internal and external developments, prepare strategic plans to deal with the future and implement day-to-day actions. Very importantly, personal standards determine the type of officers and employees that are hired in a corporation and, ultimately, the culture of the corporation, that is to say, the basic values, mores and principles by which individuals select choices in their lives and, in their working environment, make and execute corporate decisions. Reflecting on issues affecting corporate culture, values and leadership, one may start with a short vignette from the life of one of the most significant individuals in the English- speaking world, certainly in the twentieth century: Winston Spencer Churchill. On August 5, 1943, during the dark days of World War II, Prime Minister Churchill sailed on the Queen Mary from a remote port on the river Clyde on the west coast of Scotland to Halifax, Nova Scotia, with an entourage of 250. -

Starry 'Sousatzka' Team on Garth Drabinsky's Comeback Musical

SATURDAY, DECEMBER 17, 2016 Women composers US rapper Common on look to even up the movie score teaming up with 13TH s the movie business struggles with diversity and gen- merican rapper Common said it was “very special” to der equality issues, there are signs of progress on the team up again with director Ava DuVernay on her latest Amusic front: At least four features being released Adocumentary “13TH”, which deals with issues of race between now and year’s end have been scored by women, and the US criminal justice system. The Chicago native, who and at least two are expected to be major awards contenders. won a 2015 Academy Award for best song “Glory” from That may not sound like much. But consider this: No female DuVernay’s 1960s civil rights drama “Selma,” said it was impor- composer has been nominated for an original-score Oscar in tant for him to work on her latest project. “I think it’s very, very the past 15 years, and only four women have been nominated special. She is like one of those creative, passionate, intelligent in the entire 81-year history of the category. Two have won: beings and visionaries and is committed. So I’m like always British composers Rachel Portman, for “Emma,” and Anne saying, ok, what can we do?,” Common said in an interview. Dudley, for “The Full Monty.” The documentary argues that although slavery was official- “Rainbow Time,” scored by Heather McIntosh, opened Nov. ly abolished in the United States 150 years ago, it is still alive in 4. -

Parade Diverges: the 1998 Broadway and 2007 London Productions and Their Critical Receptions Julie L

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2008 Parade Diverges: The 1998 Broadway and 2007 London Productions and Their Critical Receptions Julie L. Haverkate Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF VISUAL ARTS, THEATRE & DANCE PARADE DIVERGES: THE 1998 BROADWAY AND 2007 LONDON PRODUCTIONS AND THEIR CRITICAL RECEPTIONS By JULIE L. HAVERKATE A Thesis submitted the School of Theatre in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2008 Copyright © 2008 Julie L. Haverkate All Rights Reserved The members of the Committee approve the thesis of Julie L. Haverkate defended on 19 March 2008. ______________________________ Natalya Baldyga Professor Directing Thesis ______________________________ Mary Karen Dahl Committee Member ______________________________ Tom Ossowski Committee Member ______________________________ Fred Chappel Committee Member The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Much of thesis would not have been possible without the support of Jason Robert Brown. For his infinite patience with my constant barrage of emails and questions, his willingness to meet with me, and his candid discussion of his own work, I offer my warmest and most sincere thanks. Beyond even that, and most importantly, I genuinely thank him for his continuing contributions -

Musical Theatre: a Forum for Political Expression

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Supervised Undergraduate Student Research Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects and Creative Work Spring 5-1999 Musical Theatre: A Forum for Political Expression Boyd Frank Richards University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_chanhonoproj Recommended Citation Richards, Boyd Frank, "Musical Theatre: A Forum for Political Expression" (1999). Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_chanhonoproj/337 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Supervised Undergraduate Student Research and Creative Work at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UNIVERSITY HONORS PROGRAM SENIOR PROJECT • APPROVAL -IJO J?J /" t~.s Name: -·v~ __ ~~v~--_______________ _______________________- _ J3~~~~ ____ ~~:__ d_ epartmen. ______________________ _ College: ~ *' S' '.e..' 0 t· Faculty Mentor: __ K~---j~2..9:::.C.e.--------------------------- PROJECT TITLE; _~LCQ.(__ :Jherui:~~ ___ I1 __:lQ.C1:UiLl~-- __ _ --------JI!.c. __ Pdl~'aJ___ ~J:tZ~L~ .. -_______________ _ ---------------------------------------_.------------------ I have reviewed this completed senior honors thesis with this student and certify that it is a project commensurate with honors level undergraduate research in this :::'ed: _._________ ._____________ , Faculty !v1entor Date: _LL_ -9fL-------- Comments (Optional): Musical Theater: A Forum for Political Expression Presented by: Ashlee Ellis Boyd Richards May 5,1999 Table of Contents Table of Contents ................................................................................2 Introduction: Musical Theatre - A Forum for Political Expression .................. -

LSA Template

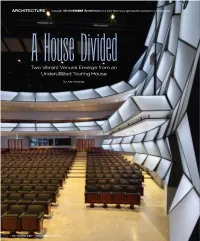

ARCHITECTURE Copyright Lighting &Sound America March 2017 http://www.lightingandsoundamerica.com/LSA.html A House Divided Two Vibrant Venues Emerge from an Underutilized Touring House By: Alan Hardiman T 44 • March 2017 • Lighting &Sound America he Toronto Centre for the Arts has taken a sword to its Diamond+Schmitt Architects. “We won the competition 1,800-seat Main Stage Theatre. In a radical approach with our proposal to divide the theatre into two spaces.” to the problem of underutilization, it has severed the One stipulation of the Main Stage reconfiguration proj - theatre into two smaller venues, sacrificing more than ect was that, in creating the two new theatres within the 900 seats in a bid to fill the remaining 870. The two existing envelope of the Eberhard Zeidler-designed Main T new venues are the 296-seat Greenwin Theatre, built Stage Theatre, the original shell would be left intact, to on the former stage of the Main Stage, and 574-seat allow the theatre to be returned to its original form, should Lyric Theatre, constructed in the original audience cham - that ever be desired. ber. Completed at a cost of just $8 million, the renovation was intended to breathe new life into a cultural destination Greenwin Theatre that had become unviable in its original form; all signs indi - The renovation fell naturally into two phases, with the cate that the effort is paying off. deadline for completing the smaller Greenwin Theatre set When the theatre opened in October 1993 as the flag - for April 18, 2015, for the sold-out world premiere of ship venue of the new North York Performing Arts Centre, Therefore Choose Life, presented by the Harold Green as it was then known, it was a different era. -

In the Matter of Garth H. Drabinsky, Myron I. Gottlieb and Gordon Eckstein

Ontario Commission des P.O. Box 55, 19th Floor CP 55, 19e étage Securities valeurs mobilières 20 Queen Street West 20, rue queen ouest Commission de l’Ontario Toronto ON M5H 3S8 Toronto ON M5H 3S8 IN THE MATTER OF THE SECURITIES ACT R.S.O. 1990, c. S.5, AS AMENDED - AND - IN THE MATTER OF GARTH H. DRABINSKY MYRON I. GOTTLIEB GORDON ECKSTEIN AMENDED STATEMENT OF ALLEGATIONS OF STAFF OF THE ONTARIO SECURITIES COMMISSION Staff of the Ontario Securities Commission (“Staff”) make the following allegations: I Convictions of Garth Drabinsky, Myron Gottlieb and Gordon Eckstein 1. On February 26, 2007, Gordon Eckstein pled guilty in the Ontario Superior Court of Justice to one count of criminal fraud over $5000 in connection with misrepresentations made in the financial statements of Livent Inc. (“Livent”) and its predecessor companies while he was an officer of these companies. 2. On March 25, 2009, Garth H. Drabinsky and Myron I. Gottlieb were found guilty in the Ontario Superior Court of Justice of two counts of criminal fraud over $5000 and one count of forgery in connection with misrepresentations made in the financial statements of Livent and its predecessor companies while they were directors and officers of these companies. 3. The convictions against Eckstein, Drabinsky and Gottlieb (together, the “Respondents”) involved financial statements used to promote the initial public offering of Livent on the Toronto Stock Exchange (the “IPO”). The financial statements, which were included in the prospectus for the IPO, materially overstated the amount of company assets and concealed a kickback scheme. 2 4. -

Staging Poetic Justice

臺大文史哲學報 第六十五期 2006年11月 頁223~250 臺灣大學文學院 Staging Poetic Justice: Public Spectacle of Private Grief in the Musical Parade Wang, Pao-hsiang∗ Abstract This paper makes inquiries into the 1998 musical Parade by playwright Alfred Uhry and composer Jason Robert Brown, based on the historic case of Leo Frank, a Jewish industrialist from New York running a pencil factory in Atlanta and accused of murdering the 13-year-old girl Mary Phagan in 1913. How can the thorny case be represented with any fidelity on stage when all the facts have not come to light? What can a theatre researcher contribute to or comment on a controversial production of a reproduction of a historical incident that has never ceased to produce great furors over the past 90 years? In the absence of irrefutable legal evidence that could close the case and in the face of contending camps that claim justice on each side, the author will stay above the litigation fray and distance himself from any attempt to pass judgment on the innocence or guilt of people involved in the historic case. Rather, the paper first probes the context surrounding the case, including war, class, race, and to a lesser extent, sexuality by examining it from the perspective of historical legacy, such as the post-bellum South reeling from the repercussions of the Civil War defeat, the regional animosity between the highly industrialized North and New Industrial South, the class antagonism of management and labor in the pencil factory, the ethnic strife between blacks, whites, and Jews, and the conventional bias against the perceived sexual perversion of Jews and blacks. -

A Celebration of Black Musical Theatre Curated by Marcus Nance

A CELEBRATION OF BLACK MUSICAL THEATRE CURATED BY MARCUS NANCE PRODUCTION SUPPORT IS GENEROUSLY PROVIDED BY MARY ANN & ROBERT GORLIN PRODUCTION CO-SPONSOR LAND ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Welcome to the Stratford Festival. It is a great privilege to gather and share stories on this beautiful territory, which has been the site of human activity — and therefore storytelling — for many thousands of years. We wish to honour the ancestral guardians of this land and its waterways: the Anishinaabe, the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, the Wendat, and the Attiwonderonk. Today many Indigenous peoples continue to call this land home and act as its stewards, and this responsibility extends to all peoples, to share and care for this land for generations to come. CURATED AND DIRECTED BY MARCUS NANCE THE SINGERS NEEMA BICKERSTETH ROBERT MARKUS MARCUS NANCE VANESSA SEARS THE BAND MUSIC DIRECTOR, KEYBOARD ACOUSTIC BASS, ELECTRIC BASS FRANKLIN BRASZ JON MAHARAJ ACOUSTIC GUITAR, ELECTRIC GUITAR DRUM KIT, ORCHESTRA SUPERVISOR KEVIN RAMESSAR DALE-ANNE BRENDON The videotaping or other video or audio recording of this production is strictly prohibited. A MESSAGE FROM OUR ARTISTIC DIRECTOR WORLDS WITHOUT WALLS Two young people are in love. They’re next- cocoon, and now it’s time to emerge in a door neighbours, but their families don’t get blaze of new colour, with lively, searching on. So they’re not allowed to meet: all they work that deals with profound questions and can do is whisper sweet nothings to each prompts us to think and see in new ways. other through a small gap in the garden wall between them. -

Byeugene Amodeo

Pioneer Book 2008:Layout 2 10/28/08 12:22 PM Page 10 by Eugene Amodeo They told me “don’t call us, we’ll call you” and they didn’t! Knowing I However, I persevered and somehow wanted to work in the film industry, I called every single film and muddled through it all! In 1974, National theatre circuit company asking if they needed anyone. That was in General sold to Warner Brothers and I June 1963 and there were no bites. So I went for an interview to be was out of a job….but only for a month. a shipper at a manufacturing company, which would pay $60 a week. I started at Astral Films as the Head I needed typing for that job and they told me they would keep the job Booker and eventually became the open for me if I took training on an electric typewriter. At the same time Sales Manager. At that time, in late August, I got a call from Famous Players Theatres Corporation Columbia Pictures had a deal with Astral to book the independent to come in for an interview. They had kept my name on file from my theatres in Canada and one of the phone call. I said no to the shipping job and started in the Famous functions of my job was to be the audit department making $40 a week. liaison between them…..and my During my audit department years, I wanted to move to the booking migraines started! department, but I was always overlooked. So in 1967, I was offered T“ here’s no business like show business….” Born in In 1980, Universal Pictures called. -

'Paradise Square' at Berkeley Rep. (Photo: Kevin Berne)

TUESDAY, JUNE 8, 2021 Subscribe Log In PRESENTED BY Home Reopening News Views Reviews App ANNOUNCEMENT ‘Paradise Square,’ produced by Garth Drabinsky, announces Broadway run By Caitlin Huston - 1 day ago CONNECT Like us on Facebook Follow us on Twitter Follow us on Instagram PRESENTED BY The company of 'Paradise Square' at Berkeley Rep. (Photo: Kevin Berne) “Paradise Square,” a new musical about race relations in New York during the 1860s, has announced a Broadway run at the Ethel Barrymore Theatre this winter. The musical, produced by Garth Drabinsky, will star Joaquina Kalukango (“Slave Play”) in a run starting Feb. 22, 2022 and an opening night on March 20. The musical will come to Broadway after a five-week engagement starting this November at Chicago’s James M. Nederlander Theatre. The production marks Drabinsky’s return to Broadway following his 2009 conviction on charges of fraud and forgery, and his subsequent prison sentence. The charges arose from Drabinsky’s time leading production company Livent, which produced “Ragtime” and “Kiss of the Spider Woman” on Broadway and several large musicals in Canada including “The Phantom of the Opera” and “Sunset Boulevard.” The story takes place in the Five Points neighborhood of New York in 1863, at which time Irish immigrants, free Black Americans and those who had escaped slavery co-existed together. The production credits the mixture of communities in Five Points with the creation of tap dance. Additional cast members include Chilina Kennedy (“Beautiful”), John Dossett (“Pippin”), Sidney DuPont (“Beautiful”), A.J. Shively (“Bright Star”), Nathaniel Stampley (“The Color Purple”), Gabrielle McClinton (“Pippin”), Jacob Fishel (“Fiddler on the Roof”) and Kevin Dennis.