Understanding and Designing Theatre Sets 7261

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tragedy, Realism, Skepticism

Tragedy, Realism, Skepticism BENJAMIN MANGRUM Many current accounts of the relationship between tragedy and modern realism present these generic traditions as not only distinct but even rigidly opposed. Critics who trace the advent of modern realism — most often through the rise of the novel — have maintained that its origins lie in the development of the middle class, the transformation of the medieval romance, the global dissemination of European civilization, or the consolidation of bourgeois ideology and subjectivity (see McKeon 2002, 52 – 63; Davidson 2004, 73 – 100; Azim 1993; Viswanathan 1989, 23 – 44). In these literary histories, the generic formation of the realist novel is the antithesis to the history of “tragic” literary forms. Indeed, the cursory dif- ference between a lengthy (prose) narrative and a concentrated (poetic) drama masks a host of tensions. The novel narrativizes middle-class values, whereas tragedies stage the fall of aristocratic or “great” houses; the realist novel purport- edly democratizes literature, while tragedies regularly presuppose some form of antipathy toward the mundane or lower classes (see Aristotle 1999, 35); a “real- ist” or secular view of history underlies the novel, while tragedy seems to enfold human agency within the forces of divine fate;1 the novel protracts drama across time, whereas tragedy intensifies it into momentous events;2 the novel is con- cerned with subjectivity (see Armstrong 2006), while tragedy explores the dis- solution of the individual, the doxastic wisdom of the chorus, or the demands of 1. In The Historical Novel (1983), Georg Lukács situates the works of Sir Walter Scott within the production of bourgeois consciousness and a view of history that contrasts sharply with its precursors, the epic and tragedy. -

The Role of Stanislavsky and the Moscow Art Theatre's 1923 And

CULTURAL EXCHANGE: THE ROLE OF STANISLAVSKY AND THE MOSCOW ART THEATRE’S 1923 AND1924 AMERICAN TOURS Cassandra M. Brooks, B.A. Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 2014 APPROVED: Olga Velikanova, Major Professor Richard Golden, Committee Member Guy Chet, Committee Member Richard B. McCaslin, Chair of the Department of History Mark Wardell, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Brooks, Cassandra M. Cultural Exchange: The Role of Stanislavsky and the Moscow Art Theatre’s 1923 and 1924 American Tours. Master of Arts (History), August 2014, 105 pp., bibliography, 43 titles. The following is a historical analysis on the Moscow Art Theatre’s (MAT) tours to the United States in 1923 and 1924, and the developments and changes that occurred in Russian and American theatre cultures as a result of those visits. Konstantin Stanislavsky, the MAT’s co-founder and director, developed the System as a new tool used to help train actors—it provided techniques employed to develop their craft and get into character. This would drastically change modern acting in Russia, the United States and throughout the world. The MAT’s first (January 2, 1923 – June 7, 1923) and second (November 23, 1923 – May 24, 1924) tours provided a vehicle for the transmission of the System. In addition, the tour itself impacted the culture of the countries involved. Thus far, the implications of the 1923 and 1924 tours have been ignored by the historians, and have mostly been briefly discussed by the theatre professionals. This thesis fills the gap in historical knowledge. -

Theatre and Drama of Socialist Realism in the Context of Cryptotexts (Based on Mkis and Wukppiw Material)

ACTA UNIVERSITATIS LODZIENSIS FOLIA LITTERARIA POLONICA 7(37) 2016 http://dx.doi.org/10.18778/1505-9057.37.06 Anna Wiśniewska-Grabarczyk* Theatre and Drama of Socialist Realism in the Context of Cryptotexts (Based on MKiS and WUKPPiW Material) The goal of the article is to discuss cryptotexts1 created in Poland during Socialist realism. The study covers documents developed by the Ministry of Cul- ture and Arts (MKiS) and the Voivodship Control Bureau for Press, Publications and Performances (WUKPPiW) in Poznań in 1949–54 discussing the methods of on-stage fulfilment of plays and dramatic works designed for younger audiences. Polish literature in the context of cryptotexts2 In the People’s Republic, all cultural texts3 which were to be released into official circulation4 were evaluated by state officers. In the majority of cases they were secret in nature and had an intentionally limited distribution which is why * Mgr, e-mail: [email protected], Chair of Polish Literature of the 20th and 21st Century, In- stitute of Polish Philology, Faculty of Philology, University of Lodz, 90-236 Łódź, ul. Pomorska 171/173. 1 Cryptotexts are defined as secret texts with deliberately limited circulation. I offer a more ex- tensive characterisation of this type of work in an article entitled Recenzja cenzorska Polski Ludowej, “Zagadnienia Rodzajów Literackich” 2016, issue 59 (117), vol. 1, pp. 97–103; cf. also footnote 5. The definition of censorship review is given in my articleSegment streszczający recenzji cenzorskiej (na materiale GUKPPiW z roku 1950), “Socjolingwistyka” 2016, issue 1 (30), pp. 278–288. 2 The title of this chapter refers to the classic text by Ryszard Nycz entitled Literatura polska w cieniu cenzury [Polish literature in the shadow of censorship], “Teksty Drugie” 1998, issue 3 (51), p. -

Hanson Brings Realism to Theater Productions

Friday, February 3, 2012 — www.theintelligencer.com Page 3 Regional Hanson brings realism to theater productions While most audiences pay attention only to the actors in theatrical productions, the Aldemaro Romero fact of the matter is that there is a con- tingent of people who work behind the College Talk scenes in order to make the performances a success. Some of these people design always look the same as they did on open- the costumes. One costume designer who ing night. “I like to say things have to is integral to the success of many per- be sewn like iron,” Hanson said. “For a formances at Southern Illinois University production say at the Rep or on Broadway Edwardsville is Laura Hanson. where things are going to run maybe for Born in Burbank, Calif., Hanson received years, there is a constant upkeep as well her bachelor’s degree in theater from St. as replacing of costumes.” There are ward- Louis University, her master’s in theater robe people whose job it is just to maintain arts also at St. Louis University and her costumes on these long-running shows, doctorate in educational theater at New she added. York University. With both of her parents Costume design is far from a lonely job. working as stage performers, her training Designers have to work not only with the in theater began early. director, but especially with the lighting “One of my favorite things to do was to designer regarding the type of light being go hang out with my mom in the dress- used or the angle of illumination. -

MARXISM and COMEDY by Max Apple

MARXISM AND COMEDY by Max Apple The "history of ideas" is one of the great obscenities in the Marxist vocab- tilary. For Marx, history is clearly the relationship of man and his available means of production. Ideas lead only to other ideas. History moves forward; the development of mankind, says the Marxist critic Lukics, "does not and cannot finally lead to nothing and nowhere."' This concept of the "end" of history is the wonder, the intellectualand emotional lure of Marxism. History has a purpose which has been subverted and disguised in the rhetoric of "Jesussaves," a rhetoric that promises the next world while this one is usurped by capital. Marxism promises this world, the only one; it translates "Christ died for you" into "history lives for you." Karl Marx is the Messiah of the industrial age. His doctrine in less than a century has already risen to chal- lenge the Christian West and its Crusades have scarcely begun. Yet, Marx's dream of a proletariat that would be free to read Aeschylus and enjoy the fruit of its labor was, from its political inception, debauched by the power struggle from which Lenin emerged. The messianic hope of Marxism has been somnolent through fifty years of Soviet Communism, but even more disturbing to the nineteenth century Marxist "world picture" are the indications that the industrial process may be moving toward an early obsolescence. In the nineteenth century a socialist could only look toward that rosy era when the workers would own the means of production; in the post- cybernetic age we will be faced with the far morc complex problems of how former workers are best able to use their emancipation from industrialism. -

Costume Design: Key Questions

Costume Design: Key Questions Costume designer and architect Gabriela Yiaxis worked with Whitechapel Gallery Children's Commission 2015 artist Rivane Neuenschwander on the exhibition The Name of Fear. Gabriela is an experienced freelance costume designer who works worldwide on feature films, advertisements, TV, fashion and music. In this resource she shares key questions and the process of taking a costume from script to screen. Rivane Neuenschwander: The Name of Fear 2015 Costume Design: Key Questions Costume designer Gabriela Yiaxis shares some of her key considerations when developing costumes for feature films. Think about how all of these questions effect what you see on screen, some of these questions can also be applied to developing costume for theatre, advertising campaigns and catwalk collections. Setting What is the story about? Is the film contemporary, futuristic, epic, period? Which exactly era? Does the storyline have a fantasy or realistic approach? How does the director wants to tell the story? Funny, realistic, surreal? Will the film be shot in black and white, sepia, colour? Who is the audience for the finished product? Costume Design: Key Questions Building a character Examples of questions you should ask yourself when they are not on a script . How old are they? Is the character rich or poor? What is their social status? Aristocracy, working class, middle class? What is the characters family background? Are they from a traditional family background, alternative family background, single parent household, grew up in care? What is the characters role in the story? Banker, waitress, doctor, athlete, writer, homeless, musician, salesman, criminal? Consider how the characters personality affects the costume. -

The Cambridge Introduction to American Literary Realism

The Cambridge Introduction to American Literary Realism PHILLIP J. BARRISH cambridge university press Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, São Paulo, Delhi, Tokyo, Mexico City Cambridge University Press Te Edinburgh Building, Cambridge CB2 8RU, UK Published in the United States of America by Cambridge University Press, New York www.cambridge.org Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9780521050104 © Cambridge University Press 2011 Tis publication is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 2011 Printed in the United Kingdom at the University Press, Cambridge A catalogue record for this publication is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication data Barrish, Phillip. Te Cambridge introduction to American literary realism / Phillip J. Barrish. p. cm. – (Cambridge introductions to literature) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-521-89769-3 (hardback) – ISBN 978-0-521-05010-4 (paperback) 1. American fction–19th century–History and criticism. 2. American fction–20th century–History and criticism. 3. Literature and society– United States–History–19th century. 4. Literature and society–United States– History–20th century. 5. Realism in literature. 6. Popular literature– United States–History and criticism. 7. National characteristics, American, in literature. I. Title. II. Series. PS374.R32B37 2011 810.9Ł1209034–dc23 2011028104 ISBN 978-0-521-89769-3 Hardback ISBN 978-0-521-05010-4 Paperback Cambridge University Press has no responsibility for the persistence or accuracy of URLs for external or third-party internet websites referred to in this publication, and does not guarantee that any content on such websites is, or will remain, accurate or appropriate. -

Reinhold Niebuhr on Tragedy, Irony and Politics

Reinhold Niebuhr on Tragedy, Irony, and Politics Copyright 2009 Daniel G. Lang [email protected] Prepared for presentation at the American Political Science Association Annual Meeting Toronto , Canada , September 3-7, 2009 Please do not cite without the author's permission. "Man stands under and in eternity. His imagination is quickened by the vision of an eternal good. Following that vision, he is constantly involved both in the sin of giving a spurious sanctity to his imperfect good and in the genuine creativity of seeking a higher good than he possesses."1 [1] Realism as an approach to thinking about politics in general and to international politics in particular has been challenged as no longer the best way to approach these subjects--if it ever was. To its critics, the realities which shaped its distinctive concerns have largely been superseded by new ones for which the realist world view provides little light and offers poor guidance. When the primary actors in international relations were nation-states, realism may have made sense. Now, because of the forces of globalization, sub-national and super-national actors must assume a prominent place in the story. Where realists tended to treat nation-states as unitary actors with domestic regime principles largely discounted, a substantial body of scholarship now supports a liberal democratic peace theory. Finally, where realists focused on a "high politics" agenda of national security, military power, and the strategic use of force, what many now say is required is sustained attention to the "low politics" of trade, economic development, global cooperation, multi-lateral diplomacy. -

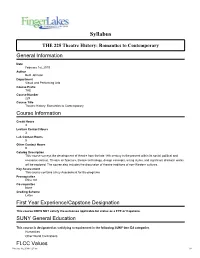

THE 225 Course Syllabus

Syllabus THE 225 Theatre History: Romantics to Contemporary General Information Date February 1st, 2019 Author Beth Johnson Department Visual and Performing Arts Course Prefix THE Course Number 225 Course Title Theatre History: Romantics to Contemporary Course Information Credit Hours 3 Lecture Contact Hours 3 Lab Contact Hours 0 Other Contact Hours 0 Catalog Description This course surveys the development of theatre from the late 18th century to the present within its social, political and economic context. Theatre architecture, theatre technology, design concepts, acting styles, and significant dramatic works will be explored. The course also includes the discussion of theatre traditions of non-Western cultures. Key Assessment This course contains a Key Assessment for the programs Prerequisites ENG 101 Co-requisites None Grading Scheme Letter First Year Experience/Capstone Designation This course DOES NOT satisfy the outcomes applicable for status as a FYE or Capstone. SUNY General Education This course is designated as satisfying a requirement in the following SUNY Gen Ed categories Humanities Other World Civilizations FLCC Values February 1st, 2019 11:25 am 1/3 Institutional Learning Outcomes Addressed by the Course Inquiry Interconnectedness Course Learning Outcomes Course Learning Outcomes 1. Identify the production styles and historical contexts of the major periods of Eastern and Western theatre history from the 1800s to the present. 2. Relate works of literature to both their socio-economic and historical context, and to the available theatre technology, architecture, and production elements. 3. Present on a modern theatrical movement such as Naturalism, Symbolism, Futurism, Surrealism, Expressionism, etc.... 4. Trace shifts in production through different theatrical periods and/or styles in order to present their findings to a classroom audience. -

Definitions of Realism and Naturalism

Definitions of Realism and Naturalism From Abrams, M.H. A Glossary of Literary Terms, 5th Edition. San Francisco: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, Inc., 1988. 152-154. Realism and Naturalism. Realism is used by literary critics in two chief ways: (1) to identify a literary movement of the nineteenth century, especially in prose fiction (beginning with Balzac in France, George Eliot in England, and William Dean Howells in America); and (2) to designate a recurrent mode, in various eras, of representing human life and experience in literature, which was especially exemplified by the writers of this historical movement. Realistic fiction is often opposed to romantic fiction: the romance is said to present life as we would have it be, more picturesque, more adventurous, more heroic than the actual; realism, to present an accurate imitation of life as it is. This distinction is not invalid, but it is inadequate. Casanova, T. E. Lawrence, and Winston Churchill were people in real life, but their histories, as related by themselves or others, demonstrate that truth can be stranger than literary realism. The typical realist sets out to write a fiction which will give the illusion that it reflects life and the social world as it seems to the common reader. To achieve this effect the author prefers as protagonist an ordinary citizen of Middletown, living on Main Street, perhaps, and engaged in the real estate business. The realist, in other words, is deliberately selective in material and prefers the average, the commonplace, and the everyday over the rarer aspects of the social p. 153 scene. -

The Melodramatic Realism of Luchino Visconti

The Melodramatic Realism of Luchino Visconti David Gariff Notes to accompany the film series Luchino Visconti at the National Gallery of Art (front cover) La terra trema November 3 through December 16, 2018 (above) Morte a Venezia (back cover) Senso Courtesy Photofest nga.gov/film 1 The Melodramatic Realism of Luchino Visconti I like melodrama because it is situated just at the In 1948 the Italian film director Luchino Visconti meeting point between life and theater. (1906 – 1976) made La terra trema (The Earth Trembles), the story of the rituals and hardships of life in the small Sicilian fish- — Luchino Visconti ing village Aci Trezza, near Catania. Based on the nineteenth- century verismo novel I malavoglia by Giovanni Verga (1840 – 1922), La terra trema is, in part, Visconti’s response to films by French directors like Jean Renoir (1894 – 1979) and René Clair (1898 – 1981). More importantly, the film is a vibrant example of the tenets of neorealism advocated in Visconti’s 1941 article “Truth and Poetry: Verga and the Italian Cinema,” which was published in the Italian avant-garde journal Cinema. The article calls for Italian filmmakers to return to the rich tradition of Italian realist literature that extends back into the nineteenth century, specifically the novels and stories of Verga. Visconti praises Verga’s stark, impersonal, and often fatalistic portray- als of human experience, as well as his sensitivity to regional dialects and customs, as inspiration for a relevant cinema that would confront the problems of modern Italy in the 1940s. With the fall of Fascism in 1943, Italian filmmakers embraced a new freedom that encouraged this direct and authentic style of movie making. -

Costume Design and Production of an Enemy of the People

Costume Design and Production of An Enemy of the People THESIS Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Fine Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Sarah Averill Fickling Graduate Program in Theatre The Ohio State University 2016 Master's Examination Committee: Kristine Kearney, Advisor Lesley Ferris Beth Kattelman Copyrighted by Sarah Averill Fickling 2016 Abstract The Ohio State University Department of Theatre’s main stage production of An Enemy of the People by Henrik Ibsen sheds a light on the egocentric lives we live in a polluted world. This production ran November 5, 2015 to November 15, 2015. With direction by Professor Lesley Ferris, scenic design by MFA Design candidate Joshua Quinlan, lighting design by MFA Design candidate Andy Baker, and sound design by undergraduate senior Michael Jake Lavender, we brought to life a unique telling of this layered story. This production of An Enemy of the People held a mirror to the audience and showed them that hypocrisy and self-serving natures still run rampant in 2015. In accordance with the director’s concept provided by Professor Ferris, I designed and executed costumes that would help the audience to subconsciously bridge the events within the play to similar events of pollution being dealt with in 2015. I accomplished this by incorporating contemporary fashion elements of 2015 into the Victorian styles and silhouettes of 1882. I used preconceived notions that the audience may have of the Victorian era to my advantage; I dressed the characters at the top of the socio-economic status in strictly period clothing and added more contemporary fashion elements to the middle and lower class characters based upon his or her status.