“Hooked on Celebri[ɾ]Y”: Intervocalic /T/ in the Speech and Song of Nina Nesbitt

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Songs by Artist

Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title &, Caitlin Will 12 Gauge Address In The Stars Dunkie Butt 10 Cc 12 Stones Donna We Are One Dreadlock Holiday 19 Somethin' Im Mandy Fly Me Mark Wills I'm Not In Love 1910 Fruitgum Co Rubber Bullets 1, 2, 3 Redlight Things We Do For Love Simon Says Wall Street Shuffle 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10 Years 1,2,3 Redlight Through The Iris Simon Says Wasteland 1975 10, 000 Maniacs Chocolate These Are The Days City 10,000 Maniacs Love Me Because Of The Night Sex... Because The Night Sex.... More Than This Sound These Are The Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH! 10,000 Maniacs Wvocal 1975, The Because The Night Chocolate 100 Proof Aged In Soul Sex Somebody's Been Sleeping The City 10Cc 1Barenaked Ladies Dreadlock Holiday Be My Yoko Ono I'm Not In Love Brian Wilson (2000 Version) We Do For Love Call And Answer 11) Enid OS Get In Line (Duet Version) 112 Get In Line (Solo Version) Come See Me It's All Been Done Cupid Jane Dance With Me Never Is Enough It's Over Now Old Apartment, The Only You One Week Peaches & Cream Shoe Box Peaches And Cream Straw Hat U Already Know What A Good Boy Song List Generator® Printed 11/21/2017 Page 1 of 486 Licensed to Greg Reil Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title 1Barenaked Ladies 20 Fingers When I Fall Short Dick Man 1Beatles, The 2AM Club Come Together Not Your Boyfriend Day Tripper 2Pac Good Day Sunshine California Love (Original Version) Help! 3 Degrees I Saw Her Standing There When Will I See You Again Love Me Do Woman In Love Nowhere Man 3 Dog Night P.S. -

Special Issue

ISSUE 750 / 19 OCTOBER 2017 15 TOP 5 MUST-READ ARTICLES record of the week } Post Malone scored Leave A Light On Billboard Hot 100 No. 1 with “sneaky” Tom Walker YouTube scheme. Relentless Records (Fader) out now Tom Walker is enjoying a meteoric rise. His new single Leave } Spotify moves A Light On, released last Friday, is a brilliant emotional piano to formalise pitch led song which builds to a crescendo of skittering drums and process for slots in pitched-up synths. Co-written and produced by Steve Mac 1 as part of the Brit List. Streaming support is big too, with top CONTENTS its Browse section. (Ed Sheeran, Clean Bandit, P!nk, Rita Ora, Liam Payne), we placement on Spotify, Apple and others helping to generate (MusicAlly) love the deliberate sense of space and depth within the mix over 50 million plays across his repertoire so far. Active on which allows Tom’s powerful vocals to resonate with strength. the road, he is currently supporting The Script in the US and P2 Editorial: Paul Scaife, } Universal Music Support for the Glasgow-born, Manchester-raised singer has will embark on an eight date UK headline tour next month RotD at 15 years announces been building all year with TV performances at Glastonbury including a London show at The Garage on 29 November P8 Special feature: ‘accelerator Treehouse on BBC2 and on the Today Show in the US. before hotfooting across Europe with Hurts. With the quality Happy Birthday engagement network’. Recent press includes Sunday Times Culture “Breaking Act”, of this single, Tom’s on the edge of the big time and we’re Record of the Day! (PRNewswire) The Sun (Bizarre), Pigeons & Planes, Clash, Shortlist and certain to see him in the mix for Brits Critics’ Choice for 2018. -

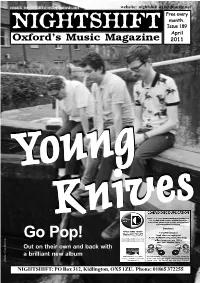

Issue 189.Pmd

email: [email protected] NIGHTSHIFTwebsite: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net Free every Oxford’s Music Magazine month. Issue 189 April 2011 YYYYYYoungoungoungoung KnivesKnivesKnivesKnives Go Pop! Out on their own and back with a brilliant new album photo: Cat Stevens NIGHTSHIFT: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU. Phone: 01865 372255 NEWNEWSS Nightshift: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU Phone: 01865 372255 email: [email protected] Online: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net WILCO JOHNSON AND listings for the weekend, plus ticket DEACON BLUE are the latest details, are online at names added to this year’s www.oxfordjazzfestival.co.uk Cornbury Festival bill. The pair join already-announced headliners WITNEY MUSIC FESTIVAL returns James Blunt, The Faces and for its fifth annual run this month. Status Quo on a big-name bill that The festival runs from 24th April also includes Ray Davies, Cyndi through to 2nd May, featuring a Lauper, Bellowhead, Olly Murs, selection of mostly local acts across a GRUFF RHYS AND BELLOWHEAD have been announced as headliners The Like and Sophie Ellis-Bextor. dozen venues in the town. Amongst a at this year’s TRUCK FESTIVAL. Other new names on the bill are host of acts confirmed are Johnson For the first time Truck will run over three full days, over the weekend of prog-folksters Stackridge, Ben Smith and the Cadillac Blues Jam, 22nd-24th July at Hill Farm in Steventon. The festival will also enjoy an Montague & Pete Lawrie, Toy Phousa, Alice Messenger, Black Hats, increased capacity and the entire site has been redesigned to accommodate Hearts, Saint Jude and Jack Deer Chicago, Prohibition Smokers new stages. -

25-29 Music Listings 4118.Indd

saturday–sunday MUSIC Ladysmith Black Mambazo Guantanamo Baywatch, Hurry Up, SUNDAY, MARCH 8 [AFRIcA’S GoLDEn tHRoAtS] the Cumstain, Pookie and Poodlez legendary, Grammy-hoarding South [GARAGE RocK] on its new single African vocal group, now halfway Retox, Whores, ”too Late,” Portland’s Guantanamo through its fifth decade, has tran- Rabbits, Phantom Family Baywatch trades its formerly scended the Western pop notori- [HARDCORE] Fatalist, nihilist, blis- reverb-flooded garage-rock sound ety that followed its contributions tering, brutal—these are just a few for tamer, Motown-influenced bal- to Paul Simon’s Graceland, becom- of the better words to describe ladry. It’s a signal that the upcom- ing a full-fledged ambassador for hardcore crew Retox, a group whose ing Darling…It’s Too Late, dropping the culture of its homeland. But pedigree includes members of sim- in May on Suicide Squeeze, may one doesn’t need familiarity with ilarly thorny outfits such as the fully shift the band away from that its lengthy history to be stirred Locust, Head Wound city and Holy signature Burger Records’ sound, by those golden voices. Aladdin Molar. one adjective that doesn’t which has flooded the market Theater, 3017 SE Milwaukie Ave., get used very often, though it with pseudo-psychedelic surf-rock 234-9694. 8 pm. $35. 21+. should, is “funny.” It’s understand- groups indistinguishable from one able that this quality wouldn’t trans- another. LUcAS cHEMOTTI. The late through singer Justin Pearson’s Low Cut Connie Know, 2026 NE Alberta St., 473- larynx-ripping screech. But Retox [tHE WHItE KEYS] An invasive 8729. -

KWLC Fall Semester 2011

KWLC Fall Semester 2011 The Fall 2011 schedule is here! From Rock, to Dubstep, Classical to Jazz, KWLC is serving up a bit of everything on the platter of commercial-free radio broadcasting this semester. Shows marked with an asterisk are web-only and stream online at luther.edu/kwlc. Monday Wednesday Friday 8–9 PM: Mike Jungbluth (Rock)* 8 – 9P: Travis Houle (Rock)* *8 – 9P: Peter Jarzyna (Rock) 9-10 PM: Logan Langley and 9 – 10P: Erik Sand and Sam Zook *9 – 10P: Dylan Hinton (Rock) Andrew Meland (Variety Hour)* (Rock/Folk Rock)* 10 – 11P: Josh Bacon and Jamison 10-11 PM: Bianca Lutchen (Rock) 10 – 11P: Joe Thor (Rock) Ash (Rock) 11-12 AM: Cate Anderson (Rock) 11 – 12A: Kelsey Simpkins (Rock) 11 – 12A: Michaela Peterson 12-1 AM: Rahul Patle and Perran 12 – 1A: Carl Sorenson (Rock) (Rock) Wetzel (House/Dubstep) 12 – 1A: Marissa Schuh (Rock) Tuesday Thursday 9–10 PM: Kenza Sahir (Acoustic *9 – 10P: Ryan Castelaz (Rock) Rock)* 10 – 11P: Seth Duin (Rock) 10–11 PM: Quincy Voris (Rock) 11 – 12A: Katherine Mohr (Rock) 11–12 AM: Gunnar Halseth (Rock) 12 – 1A: Michael Crowe (Loud 12–1 AM: Georgia Windhorst Rock) (Rock) The AM | October 7th, 2011 2 KWLC Fall Semester 2011, cont. Saturday Sunday 7 – 8A: Lilli Petsch-Horvath (Classical) 7A – 12P: Sunday Services 8 – 9A: Hannah Strack (Broadway) 12 – 1P: Maren Quanbeck (Classical) 9 – 10A: Thando May (Afro-Pop) 1 – 2P: Alex Robinson (Classical) 10 – 11A: Marin Nycklemoe (Blues) 2 – 3P: Matt Lind (Classical) 11 – 12P: Noah Lange (Bluegrass/Folk) 3 – 4P: Michael Peterson (Classical) 12 – 12:50P: Margaret Yapp (Folk) 4 – 5P: Leif Larson (Jazz) 12:50 – 4:30P: Fall Football Coverage 5 – 6P: Kevin Coughenour (Jazz) 4:30 – 5P: Kyle Holder (Rock) 6 – 7P: Ted Olsen (Jazz) 5 – 6P: Cole Matteson (Folk/Bluegrass) 7 – 8P: Fred Burdine (Jazz) 6 – 7P: Ashley Urspringer (Rock) 8 – 9P: David Clair (Jazz) 7 – 8P: Rose Weselmann (Rock) 9 – 10P: Carl Cooley (Jazz/Rock) 8 – 9P: Gene Halverson (Rock) 10 – 11P: Emily Cochrane (Rock) 9 – 10P: Imsouchivy Suos (World) 11 – 12A: Matt Dickinson (Rock) 10 – 11P: Megan Creasey (Elec. -

Ed Sheeran 30 This Week Here’S One for the Sheerios, Pop Megastar Ed Sheeran Is 30 This Week

WEEKLY BLOG wk07 and it includes an Ed Sheeran quiz to mark his 30th birthday. Welcome to the WEEKLY BLOG, available online and as a pdf download that you can print and take with you. Packed with additional content to assist quiz hosts, DJs and presenters. MID-WEEK SPORT… taking place this week Mon 15 February Premier League West Ham United v Sheffield United Chelsea v Newcastle United Tue 16 February Champion's League Barcelona v Paris Saint Germain RB Leipzig v Liverpool Wed 17 February Premier League Burnley v Fulham Everton v Manchester City Thu 18 February Europa League Real Sociedad v Manchester United RZ Pellets WAC v Tottenham Hotspur Slavia Prague v Leicester City Benfica v Arsenal Royal Antwerp v Rangers QUIZ…Ed Sheeran 30 this week Here’s one for the Sheerios, Pop megastar Ed Sheeran is 30 this week. Here is a ten question Ed Sheeran round you can add to this week’s quiz. 1 Which of the following is not the title of an Ed Sheeran album? Plus, Minus, Multiply or Divide? MINUS 2 Which fellow redhead and good friend featured in Ed Sheeran’s music video for ‘Lego House’? RUPERT GRINT 3 In the film 'Yesterday' Ed Sheeran recommended that Jack Malik changed the title of 'Hey Jude' to 'Hey... what’? HEY DUDE 4 Felix, Nigel, Lloyd and Cyril are the names of Ed Sheeran’s what? Is it brothers, his pet snakes, his garden gnomes or his guitars? GUITARS 5 Which instrument did Ed Sheeran's 'Galway Girl' play in an Irish band? FIDDLE 6 Ed Sheeran was born in West Yorkshire but brought-up in which county? SUFFOLK 7 Which Scottish singer-songwriter and ex-girlfriend was the subject of the Ed Sheeran song 'Nina'? NINA NESBITT 8 Ed Sheeran collaborated with which singer on her albums 'Red' and 'Reputation'? TAYLOR SWIFT 9 Ed Sheeran has a tattoo with a spelling mistake. -

12" White Vinyl 27.99 2Pac Thug Life

Recording Artist Recording Title Price 1975 Notes On A Conditional Form - 12" White Vinyl 27.99 2pac Thug Life - Vol 1 12" 25th Anniverary 20.99 3108 3108 12" 9.99 50 Cent Best Of 50 Cent 12" 29.99 65daysofstatic Replicr 2019 12" 20.99 Abba Live At Wembley Arena 12" - Half Speed Master 3 Lp 32.99 Abba Gold 12" 22.99 Abba Abba - The Album 12" 12.99 AC/DC Highway To Hell 12" 20.99 AC/DC Back In Black - 12" 20.99 Ace Frehley Spaceman - 12" 29.99 Acid Mothers Temple Minstrel In The Galaxy 12" 21.99 Adam & The Ants Kings Of The Wild Frontier 12" 15.99 Adele 25 12" 16.99 Adele 21 12" 16.99 Adele 19- 12" 16.99 Agnes Obel Myopia 12" 21.99 Ags Connolly How About Now 12" 9.99 Air Moon Safari 12" 14.99 Alan Marks Erik Satie - Vexations 12" 19.99 Alanis Morissette Jagged Little Pill 12" 18.99 Aldous Harding Party 12" 16.99 Aldous Harding Designer 12" 14.99 Alec Cheer Night Kaleidoscope Ost 12" 14.99 Alex Banks Beneath The Surface 12" 19.99 Alex Lahey The Best Of Luck Club 12" White Vinyl 19.99 Alex Lahey I Love You Like A Brother 12" Peach Vinyl 19.99 Alfie Templeman Happiness In Liquid Form 14.99 Algiers There Is No Year 12" Dinked Edition 26.99 Ali Farka Toure With Ry CooderTalking Timbuktu 12" 24.99 Alice Coltrane The Ecstatic Music Of... 12" 28.99 Alice Cooper Greatest Hits 12" 16.99 Allah Las Lahs 12" Dinked Edition 19.99 Allah Las Lahs 12" 18.99 Alloy Orchestra Man With A Movie Camera- Live At Third Man Records 12" 12.99 Alt-j An Awesome Wave 12" 16.99 Amazones D'afrique Amazones Power 12" 24.99 Amy Winehouse Frank 12" 19.99 Amy Winehouse Back To Black - 12" 12.99 Anchorsong Cohesion 12" 12.99 Anderson Paak Malibu 12" 21.99 Andrew Combs Worried Man 12" White Vinyl 16.99 Andrew Combs Ideal Man 12" Colour Vinyl 16.99 Andrew W.k I Get Wet 12" 38.99 Angel Olsen All Mirrors 12" Clear Vinyl 22.99 Ann Peebles Greatest Hits 12" 15.99 Anna Calvi Hunted 12" - Ltd Red 24.99 Anna St. -

Eif.Co.Uk +44 (0) 131 473 2000 #Edintfest THANK YOU to OUR SUPPORTERS THANK YOU to OUR FUNDERS and PARTNERS

eif.co.uk +44 (0) 131 473 2000 #edintfest THANK YOU TO OUR SUPPORTERS THANK YOU TO OUR FUNDERS AND PARTNERS Principal Supporters Public Funders Dunard Fund American Friends of the Edinburgh Edinburgh International Festival is supported through Léan Scully EIF Fund International Festival the PLACE programme, a partnership between James and Morag Anderson Edinburgh International Festival the Scottish Government – through Creative Scotland – the City of Edinburgh Council and the Edinburgh Festivals Sir Ewan and Lady Brown Endowment Fund Opening Event Partner Learning & Engagement Partner Festival Partners Benefactors Trusts and Corporate Donations Geoff and Mary Ball Richard and Catherine Burns Cruden Foundation Limited Lori A. Martin and Badenoch & Co. Joscelyn Fox Christopher L. Eisgruber The Calateria Trust Gavin and Kate Gemmell Flure Grossart The Castansa Trust Donald and Louise MacDonald Professor Ludmilla Jordanova Cullen Property Anne McFarlane Niall and Carol Lothian The Peter Diamand Trust Strategic Partners The Negaunee Foundation Bridget and John Macaskill The Evelyn Drysdale Charitable Trust The Pirie Rankin Charitable Trust Vivienne and Robin Menzies Edwin Fox Foundation Michael Shipley and Philip Rudge David Millar Gordon Fraser Charitable Trust Keith and Andrea Skeoch Keith and Lee Miller Miss K M Harbinson's Charitable Trust The Stevenston Charitable Trust Jerry Ozaniec The Inches Carr Trust Claire and Mark Urquhart Sarah and Spiro Phanos Jean and Roger Miller's Charitable Trust Brenda Rennie Penpont Charitable Trust Festival -

Recording Artist Recording Title Price 2Pac Thug Life

Recording Artist Recording Title Price 2pac Thug Life - Vol 1 12" 25th Anniverary 20.99 2pac Me Against The World 12" - 2020 Reissue 24.99 3108 3108 12" 9.99 65daysofstatic Replicr 2019 12" 20.99 A Tribe Called Quest We Got It From Here Thank You 4 Your Service 12" 20.99 A Tribe Called Quest People's Instinctive Travels And The Paths Of Rhythm 12" Reissue 26.99 Abba Live At Wembley Arena 12" - Half Speed Master 3 Lp 32.99 Abba Gold 12" 22.99 Abba Abba - The Album 12" 12.99 AC/DC Highway To Hell 12" 20.99 Ace Frehley Spaceman - 12" 29.99 Acid Mothers Temple Minstrel In The Galaxy 12" 21.99 Adele 25 12" 16.99 Adele 21 12" 16.99 Adele 19- 12" 16.99 Agnes Obel Myopia 12" 21.99 Ags Connolly How About Now 12" 9.99 Air Moon Safari 12" 15.99 Alan Marks Erik Satie - Vexations 12" 19.99 Aldous Harding Party 12" 16.99 Alec Cheer Night Kaleidoscope Ost 12" 14.99 Alex Banks Beneath The Surface 12" 19.99 Alex Lahey The Best Of Luck Club 12" White Vinyl 19.99 Algiers There Is No Year 12" Dinked Edition 26.99 Ali Farka Toure With Ry Cooder Talking Timbuktu 12" 24.99 Alice Coltrane The Ecstatic Music Of... 12" 28.99 Alice Cooper Greatest Hits 12" 16.99 Allah Las Lahs 12" Dinked Edition 19.99 Allah Las Lahs 12" 18.99 Alloy Orchestra Man With A Movie Camera- Live At Third Man Records 12" 12.99 Alt-j An Awesome Wave 12" 16.99 Amazones D'afrique Amazones Power 12" 24.99 American Aquarium Lamentations 12" Colour Vinyl 16.99 Amy Winehouse Frank 12" 19.99 Amy Winehouse Back To Black - 12" 12.99 Anchorsong Cohesion 12" 12.99 Anderson Paak Malibu 12" 21.99 Andrew Bird My Finest Work 12" 22.99 Andrew Combs Worried Man 12" White Vinyl 16.99 Andrew Combs Ideal Man 12" Colour Vinyl 16.99 Andrew W.k I Get Wet 12" 38.99 Angel Olsen All Mirrors 12" Clear Vinyl 22.99 Angelo Badalamenti Twin Peaks - Ost 12" - Ltd Green 20.99 Ann Peebles Greatest Hits 12" 15.99 Anna Calvi Hunted 12" - Ltd Red 24.99 Anna St. -

Record of the Week ��Music� Retail Survey Suggests Continued Importance of Ownership and Physical Formats

issue 573 / 17 April 2014 TOP 5 MUST-READ ARTICLES record of the week Music retail survey suggests continued importance of ownership and physical formats. i wanna Feel (RotD) Secondcity Ministry Of sound/speakerbox Pono’s Kickstarter round May 25 closes with $6.2m raised. (Billboard) There’s no question whatsoever that 2014’s musical land- of Zane lowe’s Hottest records in The World at radio 1. A recent Cool Cuts No.1 and currently in shazam’s pre- Syco Entertainment house anthems dominating the top end of the singles chart. release Top 10, we’ve heard Annie Mac, Mistajam, skream CEO Charles Garland Here’s the next club classic in the making. secondcity has an and loads more falling over themselves to declare their love stepping down. (Billboard) element of mystery surrounding him but what we do know so for this tune and now the stage is set for this to be another far is that he was born in Chicago but moved to london at the Spotify expected to age of 12, hence his stage name. Already on board at radio where it’s likely to sit comfortably all summer long. Keep ‘em announce US carrier deal with upfront additions to their playlists are 1Xtra, Capital and coming. with Sprint. (Recode) Capital Xtra, Kiss and Kiss Fresh plus the track has been one See page 13 for contact details Sajid Javid named CONTENTS as Culture Secretary. (Guardian) P2 Comment: Pono P3 Wide Days report P8 TGE panels focus P3 Review: Wide Days P6 The Griswolds P9 Aurora P10 Sync of the Week Plus all the regulars worldwide sales including 6am, Word On, Business News, Media marketing and Watch and Chart Life distribution 1 comment david balfour questions whether pono is the right way forward for high quality audio Neil Young’s pono high resolution audio see many people warming to them or proudly project this week completed its funding round minimum standard. -

Report Artist Release Tracktitle Streaming 2017 1Wayfrank Ayegirl

Report Artist Release Tracktitle Streaming 2017 1wayfrank Ayegirl - Single Ayegirl Streaming 2017 2 Brothers On the 4th Floor Best of 2 Brothers On the 4th Floor Dreams (Radio Version) Streaming 2017 2 Chainz TrapAvelli Tre El Chapo Jr Streaming 2017 2 Unlimited Get Ready for This - Single Get Ready for This (Yar Rap Edit) Streaming 2017 3LAU Fire (Remixes) - Single Fire (Price & Takis Remix) Streaming 2017 4Pro Smiler Til Fjender - Single Smiler Til Fjender Streaming 2017 666 Supa-Dupa-Fly (Remixes) - EP Supa-Dupa-Fly (Radio Version) Lets Lurk (feat. LD, Dimzy, Asap, Monkey & Streaming 2017 67 Liquez) No Hook (feat. LD, Dimzy, Asap, Monkey & Liquez) Streaming 2017 6LACK Loyal - Single Loyal Streaming 2017 8Ball Julekugler - Single Julekugler Streaming 2017 A & MOX2 Behøver ikk Behøver ikk (feat. Milo) Streaming 2017 A & MOX2 DE VED DET DE VED DET Streaming 2017 A Billion Robots This Is Melbourne - Single This Is Melbourne Streaming 2017 A Day to Remember Homesick (Special Edition) If It Means a Lot to You Streaming 2017 A Day to Remember What Separates Me from You All I Want Streaming 2017 A Flock of Seagulls Wishing: The Very Best Of I Ran Streaming 2017 A.CHAL Welcome to GAZI Round Whippin' Streaming 2017 A2M I Got Bitches - Single I Got Bitches Streaming 2017 Abbaz Hvor Meget Din X Ikk Er Mig - Single Hvor Meget Din X Ikk Er Mig Streaming 2017 Abbaz Harakat (feat. Gio) - Single Harakat (feat. Gio) Streaming 2017 ABRA Rose Fruit Streaming 2017 Abstract Im Good (feat. Roze & Drumma Battalion) Im Good (feat. Blac) Streaming 2017 Abstract Something to Write Home About I Do This (feat. -

FAT CAT in Participation with the Third Hasselt Culture Weekend SHOTS 2007

www.open-circuit.com PRESENTS FAT CAT in participation with the third Hasselt Culture Weekend SHOTS 2007 www.hasseltshots.be FRI 2 / 2 / 2007 múm (ISL) - NINA NASTASIA (US) - THE TWILIGHT SAD (SCOT) SILJE NES (NOR) - GANG WIZARD (US) - SEMICONDUCTOR vs ANTENNA FARM (UK) + SURPRISE COLLABORATIONS - more t.b.c.... SAT 3 / 2 / 2007 múm (ISL) - HAUSCHKA (D) - ENSEMBLE (CAN/F) THE HOSPITALS (US) - WELCOME (US) - SONGS OF GREEN PHEASANT (UK) + SURPRISE COLLABORATIONS - more t.b.c.... Where: Kunstencentrum Belgie Burgemeester Bollenstraat 54 3500 Hasselt When: Fri 2 en Sat 3 februari 2007 Doors: as of 19h00 Tickets: day ticket EUR 17 (members belgie) / EUR 20 weekend ticket: EUR 30 (leden belgie) / EUR 35 RESERVATIONS: STRONGLY ADVICED! By phone or email: 0032 11 22 41 61 or [email protected] With the support of: The Flemish Government The Province of Limburg The City of Hasselt The two day OPEN CIRCUIT: FAT CAT festival which took place in kunstencentrum BELGIE du- ring the culture weekend SHOTS in the city of Hasselt in 2006 was a big succes. Concerts, performan- ces and collaborations of Vashti Bunyan, múm dj’s, Max Richter and Our Brother The Native were received very well by press and audience. The OPEN CIRCUIT production platform and the English label Fat Cat are joining forces again in 2007 to add a new and inspiring edition of the internationaly renowned festival. Both nights will be headlined by Iceland’s múm (appearing for the first time in a reduced but chal- lenging 5-piece line-up). There will be sets from a large number of FatCat artists and friends, inclu- ding debut European shows for The Twilight Sad, Songs Of Green Pheasant, Silje Nes, Gang Wizard, Ensemble, and Welcome.