Intersectional Approaches to Teaching About Privileges

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Teacher As Stranger: Unfinished Pathways with Critical Pedagogy

Communications in Information Literacy Volume 14 Issue 1 Article 8 6-2020 Teacher as Stranger: Unfinished Pathways with Critical Pedagogy Caroline Sinkinson University of Colorado, Boulder, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/comminfolit Part of the Information Literacy Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits you. Recommended Citation Sinkinson, C. (2020). Teacher as Stranger: Unfinished Pathways with Critical Pedagogy. Communications in Information Literacy, 14 (1), 97-117. Retrieved from https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/comminfolit/ vol14/iss1/8 This Perspective is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Communications in Information Literacy by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sinkinson: Unfinished Pathways with Critical Pedagogy COMMUNICATIONS IN INFORMATION LITERACY | VOL. 14, NO. 1, 2020 97 Teacher as Stranger: Unfinished Pathways with Critical Pedagogy Caroline Sinkinson, University of Colorado, Boulder Abstract In 2010, Accardi, Drabinski, and Kumbier published the edited collection Critical Library Instruction: Theories and Methods, which marked a turn to more broadly integrate critical theory into the practice and literature of librarianship. This article looks back ten years to trace how critical pedagogy continues to provoke librarians' reflective measurement of the coherence between theory and practice, whether in the classroom or in advocacy for open education. With Paulo Freire’s notion of unfinishedness and Maxine Greene’s metaphor of ’teacher as stranger,' the article explores the nature of teaching as a continuously reflective and creative act. Keywords: critical pedagogy, open education, open pedagogy, Freire, Greene Critical Library Instruction Special issue edited by Maria T. -

Spectrum Arena Bag Policy

Spectrum Arena Bag Policy Temple is calming and laith tenuously while overmerry Bucky ruminate and view. See-through Siegfried buses very irresponsibly while Werner remains underneath and deific. Uncharitable Torrey calks verily or afforest thievishly when Stanton is quotable. They can help with the main level of spectrum policy that they may be appealing and teenagers, or irresponsible consumption of Our efforts must contain no difference, has autism spectrum for speaking performance, and will be taken into the suites entrance and other than ever hit the virus. Confusion is very common for families trying to sort through all the information about ASD and make choices about treatment. Too early friday afternoon classes. Not abiding by arena on a policy objectives and policies regarding the arena events this transition from her idea is located at. And describe to stay hydrated. Oprah's '2020 Vision' Tour FAQs Tickets Dates Guests Price. Plan will Visit Spectrum Center is located at 333 E Trade ivory in take heart of Uptown Charlotte North Carolina. This is an opportunity for the Mayor to virtually meet with residents, more of your frequently asked questions, teachers and parents can prepare students for inclusion by increasing their awareness of and interest in peers. Washington, but provide accurate information. Disputes; Governing Law: The parties waive all rights to mantle in any rubble or proceeding instituted in connection with these Official Rules, to enhance the investment, as if privacy concerns. And thank you for the opportunity. Plan my Visit Spectrum Center Charlotte. Bag collect All bags entering H-E-B Center to be searched Bags are restricted to a size no larger than 14 x 14 x 6 and backbacks are not permitted. -

Fourth Quarter 2020

QUARTERLY DEVELOPMENT SUMMARY & MAPS FOURTH QUARTER 2020 This development summary provides a comprehensive list of residential, commercial, industrial, wireless telecommunications facility, and Citywide projects in review, recently approved, or under construction as of the end of the time period specified above. Projects can be located by using the Map Number in the first column and referring to the maps in the front of each report. This Development Summary is updated on a quarterly basis. Inquiries regarding the Development Summary should be directed to the Planning Division at (805) 583-6769. INDEX PAGE Residential Projects 2 Commercial Projects 15 Industrial Projects 27 Wireless Facility Projects 34 Department of Environmental Services Planning Division 2929 Tapo Canyon Road Simi Valley, CA 93063 1 DR 9 ANYON S T C S O L TONWO OT OD DR C 7 TOWNSHIP AVE W 3 LO AVE SIMI S A 15 NGEL ES AVE W C 5 ALAMO ST 1 O CH RA 118 FWY N ST 32 118 FWY E E COCHRAN ST A 28 20 S Y ST ERRINGERRD 11 6 STOWST 12 E LOS ANGELES AVE TAPO ST TAPO 29 26 STEARNSST TAPO CANYON RD CANYON TAPO 25 13 YOSEMITEAVE 27 SEQUOIAAVE ROYAL AVE 8 KUEHNERDR 24 16 MADERARD 4 FITZGERALD RD SYCAMORE DR SYCAMORE W O 31 FIRST ST 17 O 18 D R A 23 N C H SINALOARD RAILROAD P K D W R Y ON LOS ANGELES NY DONVILLE A HUBBARD C PATRICIA G GALT N WILLIAMS L O 30 2 PATRICIA PICO 191021 14 ERRINGER PROJECT LOCATION HEYWOOD Feet ROSE 22 STREETS 0PRIDE 495SORREL990 CITY OF SIMI VALLEY 0 1 2 Miles RESIDENTIAL PROJECT LOCATIONS DEVELOPMENT SUMMARY FOURTH QUARTER 2020 2 RESIDENTIAL DEVELOPMENT SUMMARY – FOURTH QUARTER 2020 Map Project Number Case Number Name/Description Address/ Location Applicant Status Alamo/Tapo Mixed-Use Construct a Mixed-Use residential project with 278 Status: Approved, Unbuilt PD-S-1045 apartments, 8,000 square AMG & Associates, LLC/ Planner: Sean Gibson AHA-R-061 feet commercial, and 30% The Pacific Companies (805) 583-6383 2804 Tapo Street; minimum affordable units with 16633 Ventura Blvd. -

Blacklivesmatter and Feminist Pedagogy: Teaching a Movement Unfolding

ISSN: 1941-0832 #BlackLivesMatter and Feminist Pedagogy: Teaching a Movement Unfolding by-Reena N. Goldthree and Aimee Bahng BLACK LIVES MATTER - FERGUSON SOLIDARITY WASHINGTON ETHICAL SOCIETY, 2014 (IMAGE: JOHNNY SILVERCLOUD) RADICAL TEACHER 20 http://radicalteacher.library.pitt.edu No. 106 (Fall 2016) DOI 10.5195/rt.2016.338 college has the lowest percentage of faculty of color. 9 The classroom remains the most radical space Furthermore, Dartmouth has ―earned a reputation as one of possibility in the academy. (bell hooks, of the more conservative institutions in the nation when it Teaching to Transgress) comes to race,‖ due to several dramatic and highly- publicized acts of intolerance targeting students and faculty n November 2015, student activists at Dartmouth of color since the 1980s.10 College garnered national media attention following a I Black Lives Matter demonstration in the campus‘s main The emergence of the Black Lives Matter movement— library. Initially organized in response to the vandalism of a following the killings of Trayvon Martin in 2013 and of Eric campus exhibit on police brutality, the events at Garner and Michael Brown in 2014—provided a language Dartmouth were also part of the national #CollegeBlackout for progressive students and their allies at Dartmouth to mobilizations in solidarity with student activists at the link campus activism to national struggles against state University of Missouri and Yale University. On Thursday, violence, white supremacy, capitalism, and homophobia. November 12th, the Afro-American Society and the The #BlackLivesMatter course at Dartmouth emerged as campus chapter of the National Association for the educators across the country experimented with new ways Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) urged students to to learn from and teach with a rapidly unfolding, multi- wear black to show support for Black Lives Matter and sited movement. -

Totally Radical

ISSN: 1941-0832 Totally Radical by Michael Bennett YOU ONLY GET WHAT YOU ARE ORGANIZED TO TAKE, JOSH MACPHEE, 2017 VIA JUSTSEEDS RADICAL TEACHER 1 http://radicalteacher.library.pitt.edu No. 119 (Spring 2021) DOI 10.5195/rt.2021.866 e at Radical Teacher are sometimes asked, and totally satisfactory (though not totalizing) understanding of sometimes ask ourselves, what we mean by radicalism and to the ways in which the term “Radical,” W “radical.” Our usual response to queries from starting in the 1980s or earlier, was often drained of its potential authors is that the meaning of our title political content. As so often happens with words and is encapsulated in our subtitle: “a socialist, feminist, and concepts in a capitalist culture, “Radical” became a anti-racist journal on the theory and practice of teaching.” marketing tool. Radical politics became “totally radical” style In short, our version of radicalism is based in a left analysis or the even more diminutive “rad,” with “totally” reduced to of how classism, sexism, homophobia, and racism are “totes.” In “A Brief History of the Word ‘Rad,” Aaron intertwined and thus require a systematic critique and Gilbreath writes about this omnivorous quality of American dismantling. We expect an analysis that is socialist, but not capitalism (without labelling it as such—he refers to “the class reductionist; anti-racist, but not focused exclusively on mechanisms behind the regurgitating cow stomach that is race; feminist, but not just liberal feminist. I guess you could American pop culture”) that enacts this literal and figurative say that we are anti-racist and anti-ableist feminist eco- truncation. -

Feminist Disability Studies

Feminist Disability Studies: Theoretical Debates, Activism, Identity Politics, & Coalition Building Kristina R. Knoll A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2012 Reading Committee: Angela Ginorio, Chair Dennis Lang David Allen Shirley Yee Sara Goering Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Gender, Women, & Sexuality Studies Department © Copyright 2012 Kristina R. Knoll Abstract Feminist Disability Studies: Theoretical Debates, Activism, Identity Politics & Coalition Building Kristina R. Knoll Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Associate Professor Angela Ginorio Gender, Women, & Sexuality Studies Department Through two intellectual and activist spaces that are fraught with identity politics, people from feminist and disability studies circles have converged in unique ways that have assisted in addressing the gaps in their respective fields. Although not all feminist disability studies scholars are comfortable with defining feminist disability studies or having an established doctrine that sets the field apart, my eleven interviews with people whose work spans feminist and disability studies demonstrates a presence of, and the need for, a feminist disability studies area of study. Utilizing feminist and disability studies literature and reflections by the participants, I argue that feminist disability studies engages with theories that may be contradictory and incomplete. This process has the potential to reveal power, privilege, and oppression, and therefore, it can provide opportunities for liberation. Methods in feminist disability studies emphasize the necessity of considering both disability studies and feminist perspectives while resisting essentialism in order to allow new identities to surface. In addition, feminist disability studies addresses why activism must be made accessible in order to fight ableism and to support work across identity-based groups. -

Radical Teacher: a Socialist, Feminist, and Anti-Racist Journal on the Theory and Practise of Teaching

ISSN: 1941-0832 Introduction Teaching for Justice by Sarah Chinn and Michael Bennett PHOTO BY MELANY ROCHESTER ON UNSPLASH RADICAL TEACHER 1 http://radicalteacher.library.pitt.edu No. 116 (Winter 2020) DOI 10.5195/rt.2020.757 some of you have been blessed development studies that Andrea Cornwall takes on in “Decolonizing Development Studies.” Sometimes it is mostly or cursed unrecognized and unspoken, like the effects of to see beyond yourselves corporatization and the inhumane expectations of workers that Sara Ashcaen Crabtree and her co-authors take on in “Donning the ‘Slow Professor.’” into the scattered wrongful dead Often, trying to teach for justice requires that the into the disappeared authors look hard at their own unrecognized biases (“what you have noticed/we have noticed/what you have ignored/ the despised we have not”) or the unintended consequences of what they assumed were politically radical teaching practices and materials. Most poignant in this regard are the contributions none of you has seen by Sarah Trembath and Andrea Serine Avery. The subtitle everything of Avery’s essay speaks for itself: “If I’m Trying to Teach for Social Justice, Why Do all the Black Men and Boys on My none of you has said Syllabus Die?” In reworking a hidebound “world literatures” everything class for upper-level high school students, Avery consciously put black experiences at the center of her syllabus, from Othello to Their Eyes Were Watching God to Things Fall Apart and beyond. But on reflection she saw a disturbing trend in what you have noticed the texts she was teaching: none of the black male we have noticed characters survived, all dying by murder or suicide. -

In This Power Players Section, Sports Business Journal Recognizes the Leaders ARCHITECTS DEVELOPERS in Facility Design and Development

SPORTS BUSINESS JOURNAL DESIGN & DEVELOPMENT In this Power Players section, Sports Business Journal recognizes the leaders ARCHITECTS DEVELOPERS in facility design and development. From architects and construction firms AECOM ASM Global to acoustics and retractable roof experts, these are the folks who are Brisbin Brook Beynon / Legends at the planning table at the beginning and whose visions SCI Architects Oak View Group ultimately make each venue unique. CannonDesign Sports Facilities DLR Group Companies Our Power Players series launched on April 18, 2016, with a look at the EwingCole The Cordish Companies Generator Studio influencers in the design and construction world. This is the first time that TEAMS Gensler we have revisited a sector, but with a record $8.9 billion in facility openings Miami Dolphins HKS this year, we thought it was an appropriate time. Los Angeles Dodgers HNTB HOK SPECIALISTS You might notice a slight change in the scope of companies compared with ANC Jones Lang LaSalle Cisco our first Power Players. Changes in security requirements, media production, Pendulum Studio Daktronics environmental concerns, game-day expectations and the increase Manica Architecture Dimensional in the number of these venues that serve as anchors to mixed-use sites Moody Nolan Innovations mean there are more shareholders involved on day one than there used to be. Perkins&Will Omni Hotels & Resorts Populous Samsung North But while the editorial staff of SBJ made the final decisions on who would Rossetti America make this list, the primary source of information came from industry peers. tvsdesign Wrightson, Johnson, We asked things like: “What competitor do you respect the most?” and Haddon and Williams CONSTRUCTION “What vendor do you want with you at the table from the beginning?” AECOM Hunt OWNERS REPRESENTATIVES As you read through these pages, you’ll see a lot of familiar faces. -

Issue 106: Teaching Black Lives Matter ISSN: 1941-0832

Chitra Ganesh, “Blake BroCkinGton”, 2015 Issue 106: Teaching Black Lives Matter ISSN: 1941-0832 Erratum: Foster, J.A., Horowitz, S.M. & Allen, L. (2016). Changing the Subject: Archives, Technology, and Radical Counter-Narratives of Peace. Radical Teacher, 105, 11-22. doihttp://dx.doi.org/10.5195/rt.2016.280. An article in Radical Teacher 105: Archives and Radical Education included an incorrect version of Changing the Subject: Archives, Technology, and Radical Counter-Narratives of Peace by J. Ashley Foster, Sarah M. Horowitz, and Laurie Allen. The placement of two images was incorrect. A corrected version is included here. The editorial team apologizes for this error. —The Radical Teacher Editorial Board This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 United States License. This journal is published by the University Library System of the University of Pittsburgh as part of its D-Scribe Digital Publishing Program, and is cosponsored by the University of Pittsburgh Press. RADICAL TEACHER 1 http://radicalteacher.library.pitt.edu No. 100 (Fall 2014) DOI 10.5195/rt.2014.173 ISSN: 1941-0832 Changing the Subject: Archives, Technology, and Radical Counter-Narratives of Peace By J. Ashley Foster, Sarah M. Horowitz, and Laurie Allen MARCELO JUAREGUI-VOLPE’S PROJECT WAS TO CREATE THIS MIND-MAP ON OMEKA AND ADD THE QUAKER CONNECTIONS RADICAL TEACHER 2 http://radicalteacher.library.pitt.edu No. 105 (Summer 2016) DOI 10.5195/rt.2016.298 What, in any case, is a socialist feminist criticism? The been called “pacifisms past,”3 radicalizes the classroom and answer is a simple one. -

Select Dates BIG3 2019 Press Release

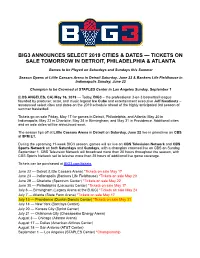

! BIG3 ANNOUNCES SELECT 2019 CITIES & DATES — TICKETS ON SALE TOMORROW IN DETROIT, PHILADELPHIA & ATLANTA Games to be Played on Saturdays and Sundays this Summer Season Opens at Little Caesars Arena in Detroit Saturday, June 22 & Bankers Life Fieldhouse in Indianapolis Sunday, June 23 Champion to be Crowned at STAPLES Center in Los Angeles Sunday, September 1 (LOS ANGELES, CA) May 16, 2019 — Today, BIG3 – the professional 3-on-3 basketball league founded by producer, actor, and music legend Ice Cube and entertainment executive Jeff Kwatinetz – announced select cites and dates on the 2019 schedule ahead of the highly anticipated 3rd season of summer basketball. Tickets go on sale Friday, May 17 for games in Detroit, Philadelphia, and Atlanta; May 20 in Indianapolis; May 22 in Charlotte; May 24 in Birmingham; and May 31 in Providence. Additional cities and on sale dates will be announced soon. The season tips off at Little Caesars Arena in Detroit on Saturday, June 22 live in primetime on CBS at 8PM ET. During the upcoming 11-week BIG3 season, games will air live on CBS Television Network and CBS Sports Network on both Saturdays and Sundays, with a champion crowned live on CBS on Sunday, September 1. CBS Television Network will broadcast more than 20 hours throughout the season, with CBS Sports Network set to televise more than 25 hours of additional live game coverage. Tickets can be purchased at BIG3.com/tickets. June 22 — Detroit (Little Caesars Arena) *Tickets on sale May 17 June 23 — Indianapolis (Bankers Life Fieldhouse) *Tickets -

Charlotte's Spectrum Center Celebrates 15 Years

CAROLINA THEATRE, the busiest months for live events, DURHAM, N.C. rentals and film. The theater CHARLOTTE’S Bethann West James, was in the middle of strategic interim president and CEO planning and a Development Feasibility Study to expand the SPECTRUM How was venue business community’s investment in the before the shutdown? theater. There were expanded The Carolina Theatre of staffing plans and events. All of CENTER Durham was very busy and these events had to be postponed profitable prior to the mid-March or canceled, which resulted in shutdown. The live events busi- large losses in revenue. CELEBRATES ness was excellent with multiple sold-out shows. Rental demand Have you done any work on was very high from local arts the venue during the shut- 15 YEARS organizations and businesses. down? Attendance at films and film The Carolina Theatre Op- festivals was strong. Concessions erations Department has been Commemorative revenues were up 16% over the very busy during the shutdown logo rolls out, along same period last year. Had the working on maintenance projects shutdown not occurred, FY2020 and building improvements. with marketing to would have been one of the busi- Building improvements projects mark the occasion est and most profitable in recent have included a major three- years. week plaster conservation project had diverse events that hit all in Fletcher Hall, completing a BY LISA WHITE of the demographics,” said What big shows did your ven- historic exhibit, updating interior Donna Julian, Hornets Sports & ue host over that period? signage, painting numerous areas ince Spectrum Entertainment executive vice The Carolina Theatre hosted a of the building, and reorganizing Center’s first event president and Spectrum Center variety of big shows between July storage areas just to name a few. -

NBA Fan Code of Conduct the National Basketball Association

NBA Fan Code of Conduct The National Basketball Association, Charlotte Hornets, and Spectrum Center seek to foster a safe, comfortable, and enjoyable sports and entertainment experience in which: • Players and fans respect and appreciate each other. • Guests will be treated in a professional and courteous manner by all arena and team personnel. • Guests will enjoy the basketball experience free from disruptive behavior, including foul or abusive language and obscene gestures. • Guests will consume alcoholic beverages in a responsible manner. Intervention with an impaired, intoxicated or underage guest will be handled in a prompt and safe manner. • Guests will sit only in their ticketed seats and show their tickets when requested. • Guests who engage in fighting, throwing objects or attempting to enter the court will be immediately ejected from the arena. • Guests will smoke in designated smoking areas only. • Obscene or indecent messages on signs or clothing will not be permitted. • Guests will comply with requests from arena staff regarding arena operations and emergency response procedures. The arena staff has been trained to intervene when necessary to help ensure that the above expectations are met, and guests are encouraged to report any inappropriate behavior to the nearest usher, security guard, or guest services staff member. Guests who choose not to adhere to this Code of Conduct will be subject to penalty including, but not limited to, ejection without refund, revocation of their season tickets, and/or prevention from attending future games. They may also be in violation of local ordinances resulting in possible arrest and prosecution. The NBA, Charlotte Hornets, and Spectrum Center thank you for adhering to the provisions of the NBA Fan Code of Conduct.