Assessment of NOAA National Weather Service Methods to Warn for Extreme Heat Events

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Heat Wave Safety Tips

Heat Wave Safety Tips KNOW THE FACTS Heat waves usually consist of high temperatures and high relative humidity. This combination makes it difficult for the human body to dissipate heat through the skin and sweat glands. Sweating will not cool the human body unless the water is removed by evaporation. High relative humidity, consequently, retards evaporation. Certain medications can also make it difficult for a person to sweat. Heat Index… The National Weather Service (NWS) uses the "HEAT INDEX" as a measure of the combined affects of high temperatures and high relative humidity. Research findings strongly suggest that HEAT INDEX (HI) values of 90 to 105 degrees make sunstroke, heat cramps, and heat exhaustion possible with prolonged exposure and/or physical activity. Research findings strongly suggest that HI vales of 105 to 130 degrees make sunstroke, heat cramps, and heat exhaustion likely with prolonged exposure and/or physical activity. Advisories and warnings… The NWS issues Heat Advisories when it expects daytime HI's to equal or exceed 105 degrees for 3 hours or more while nighttime HI's equal or exceed 80 degrees, for any 24- hour period. The NWS issues Excessive Heat Warnings when it expects daytime HI's to equal or exceed 115 degrees for 3 hours or more while nighttime HI's equal or exceed 80 degrees, for any 24-hour period. The NWS may issue an "Excessive Heat Watch" 24 to 8 hours in advance of heat wave conditions. DURING THE HEAT Listen to your NOAA Weather Radio… Stay informed about the latest watches, warnings, and advisories. -

EXTREME HEAT TOOLKIT a Planning Guide for Public Health and Emergency Response Professionals

EXTREME HEAT TOOLKIT A planning guide for public health and emergency response professionals WISCONSIN CLIMATE AND HEALTH PROGRAM Bureau of Environmental and Occupational Health dhs.wisconsin.gov/climate | [email protected] State of Wisconsin | Department of Health Services | Division of Public Health | P-00632 (Rev. 04/2019) 1 CONTENTS Introduction Definitions Guides Guide 1: Definitions of Heat Alerts Guide 2: Heat Illnesses and Symptoms Guide 3: Extreme Heat Tips Guide 4: Populations Vulnerable to Heat Guide 5: Talking Points for Heat-Related Fatality Guide 6: Message Maps about Heat-Related Safety Guide 7: Long-Term Preparation Checklist Guide 8: Anticipation of Imminent Heat Event Checklist Guide 9: Extreme Heat Event Response Checklist Appendices Appendix A: References Appendix B: Additional Resources Appendix C: Sample Heat Response Plan ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Wisconsin Extreme Heat Toolkit was made possible through funding from cooperative agreement 5UE1/ EH001043-02 from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the commitment of many individuals at the Wisconsin Department of Health Services (DHS) who contributed their valuable time and knowledge to its development. Special thanks to: Jeffrey Phillips, RS, Director of the Bureau of Environmental and Occupational Health, DHS Megan Christenson, MS, MPH, Epidemiologist, DHS Brooke Thompson, MPH, Healthy Homes Program Manager, DHS Stephanie Krueger, Public Health Associate, CDC/ DHS Eleanor Ganz, BRACE Toolkits Intern, DHS For more information, please contact: Colleen Moran, MS, MPH Climate and Health Program Manager Bureau of Environmental and Occupational Health 1 W. Wilson St., Room 150 Madison, WI 53703 [email protected] 608-266-6761 2 INTRODUCTION Purpose The purpose of this Extreme Heat Toolkit is to provide information to local governments, health departments, and citizens about preparing for and responding to heat events. -

National Weather Service Reference Guide

National Weather Service Reference Guide Purpose of this Document he National Weather Service (NWS) provides many products and services which can be T used by other governmental agencies, Tribal Nations, the private sector, the public and the global community. The data and services provided by the NWS are designed to fulfill us- ers’ needs and provide valuable information in the areas of weather, hydrology and climate. In addition, the NWS has numerous partnerships with private and other government entities. These partnerships help facilitate the mission of the NWS, which is to protect life and prop- erty and enhance the national economy. This document is intended to serve as a reference guide and information manual of the products and services provided by the NWS on a na- tional basis. Editor’s note: Throughout this document, the term ―county‖ will be used to represent counties, parishes, and boroughs. Similarly, ―county warning area‖ will be used to represent the area of responsibility of all of- fices. The local forecast office at Buffalo, New York, January, 1899. The local National Weather Service Office in Tallahassee, FL, present day. 2 Table of Contents Click on description to go directly to the page. 1. What is the National Weather Service?…………………….………………………. 5 Mission Statement 6 Organizational Structure 7 County Warning Areas 8 Weather Forecast Office Staff 10 River Forecast Center Staff 13 NWS Directive System 14 2. Non-Routine Products and Services (watch/warning/advisory descriptions)..…….. 15 Convective Weather 16 Tropical Weather 17 Winter Weather 18 Hydrology 19 Coastal Flood 20 Marine Weather 21 Non-Precipitation 23 Fire Weather 24 Other 25 Statements 25 Other Non-Routine Products 26 Extreme Weather Wording 27 Verification and Performance Goals 28 Impact-Based Decision Support Services 30 Requesting a Spot Fire Weather Forecast 33 Hazardous Materials Emergency Support 34 Interactive Warning Team 37 HazCollect 38 Damage Surveys 40 Storm Data 44 Information Requests 46 3. -

Hazard Criteria

NWS San Diego All-Hazard Reference Guide Warnings and Advisories are issued 12 to 48 hours in advance. Watches are issued when warning level conditions are forecast within the next 36 to 48 hours, or up to 72 hours with high confidence. High Winds/Blowing Dust Blowing High Wind Dust Storm Region Wind Advisory Dust Warning Warning Advisory Coastal and Sustained ≥ 30 mph Sustained ≥ 40 mph Visibility Visibility Valley areas or gust ≥ 35 mph gust ≥ 58 mph ¼ to 1 mile <¼ mile Mountains and Sustained ≥ 35 mph Sustained ≥ 45 mph Visibility Visibility Deserts or gust ≥ 40 mph or gust ≥ 58 mph ¼ to 1 mile <¼ mile < 7000 feet Mountains Sustained ≥ 40 mph Sustained ≥ 40 mph Visibility Visibility > 7000 feet or gust ≥ 55 mph or gust ≥ 75 mph ¼ to 1 mile <¼ mile Winter Weather Winter Winter Blizzard Wind Chill Wind Chill Region Weather Storm Warning Advisory Warning Advisory Warning 4-8” in Sustained winds Wind Chill 12” in 12 hours, Wind Chill Mountains 12 hours, > 35 mph and Temperatures 18” in 24 hours, Temperatures > 7000 feet or 8-12” in visibility <¼ mile from High Impact < -20 ◦F 24 hours in blowing snow -10 to -20 ◦F 3-6” in Sustained winds Wind Chill Mountains 8” in 12 hours, Wind Chill 12 hours, > 35 mph and Temperatures 3000 to 12” in 24 hours, Temperatures 4-8” in visibility <¼ mile from 7000 feet High Impact < -20 ◦F 24 hours in blowing snow -10 to -20 ◦F Other areas 1-4” in Sustained winds Wind Chill including 4” in 12 hours, Wind Chill 12 hours, > 35 mph and Temperatures High 6” in 24 hours, Temperatures 3-6” in visibility <¼ mile -

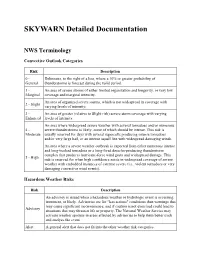

SKYWARN Detailed Documentation

SKYWARN Detailed Documentation NWS Terminology Convective Outlook Categories Risk Description 0 - Delineates, to the right of a line, where a 10% or greater probability of General thunderstorms is forecast during the valid period. 1 - An area of severe storms of either limited organization and longevity, or very low Marginal coverage and marginal intensity. An area of organized severe storms, which is not widespread in coverage with 2 - Slight varying levels of intensity. 3 - An area of greater (relative to Slight risk) severe storm coverage with varying Enhanced levels of intensity. An area where widespread severe weather with several tornadoes and/or numerous 4 - severe thunderstorms is likely, some of which should be intense. This risk is Moderate usually reserved for days with several supercells producing intense tornadoes and/or very large hail, or an intense squall line with widespread damaging winds. An area where a severe weather outbreak is expected from either numerous intense and long-tracked tornadoes or a long-lived derecho-producing thunderstorm complex that produces hurricane-force wind gusts and widespread damage. This 5 - High risk is reserved for when high confidence exists in widespread coverage of severe weather with embedded instances of extreme severe (i.e., violent tornadoes or very damaging convective wind events). Hazardous Weather Risks Risk Description An advisory is issued when a hazardous weather or hydrologic event is occurring, imminent, or likely. Advisories are for "less serious" conditions than warnings that may cause significant inconvenience, and if caution is not exercised could lead to Advisory situations that may threaten life or property. The National Weather Service may activate weather spotters in areas affected by advisories to help them better track and analyze the event. -

Inclement Weather Guidelines for Outdoor Events

INCLEMENT WEATHER GUIDELINES FOR OUTDOOR EVENTS “Inclement weather” is a generic term often used to describe weather conditions that are either unsafe or undesirable for outdoor events. Inclement weather can come in many different forms, as outlined below. This guideline is intended to be used as a tool to help you identify when forecasted or actual weather conditions require cancelling or postponing an event. NOTE: This checklist addresses only the most unsafe weather conditions. Your own event guidelines may dictate actions for other weather conditions that may be undesirable (e.g. rainy, too warm, too cold). Should any of the following triggers occur or become forecasted for the time of the event, the event should be cancelled or, when appropriate, temporarily postponed for safety reasons. Temporarily postponing an event means just waiting a few minutes until the immediate hazard passes, if your schedule allows. When in doubt about what to do, consult with FSU Emergency Management for decision support. ADVANCED NOTICE TRIGGER TO CANCEL EVENT: TRIGGER TO TEMPORARILY POSTPONE TIMEFRAME EVENT: 0 ‐ 48 Hours [ ] Hurricane or Tropical Storm Watch [ ] Winter Storm Watch 0 ‐ 24 Hours [ ] Heat Advisory or Excessive Heat Watch [ ] High Wind Watch [ ] Winter Weather Advisory [ ] Wind Chill Advisory 0 ‐ 12 Hours [ ] Tornado Watch [ ] Severe Thunderstorm Watch [ ] Flash Flood Watch [ ] Excessive Heat Warning [ ] Wind Advisory During Event [ ] Observed Heat Index in excess of 108’F. [ ] FSU ALERT issued for Tornado Warning, Severe Thunderstorm Warning, Flash Flood Warning or [ ] Observed Wind Chill less than 0’F. Lightning Warning. [ ] Observed winds in excess of 35 miles per hour. [ ] Significant Weather Advisory (no FSU ALERT). -

National Weather Service Reference Guide

National Weather Service Reference Guide Purpose of this Document he National Weather Service (NWS) provides many products and services which can be T used by other governmental agencies, Tribal Nations, the private sector, the public and the global community. The data and services provided by the NWS are designed to fulfill us- ers’ needs and provide valuable information in the areas of weather, hydrology and climate. In addition, the NWS has numerous partnerships with private and other government entities. These partnerships help facilitate the mission of the NWS, which is to protect life and prop- erty and enhance the national economy. This document is intended to serve as a reference guide and information manual of the products and services provided by the NWS on a na- tional basis. Editor’s note: Throughout this document, the term ―county‖ will be used to represent counties, parishes, and boroughs. Similarly, ―county warning area‖ will be used to represent the area of responsibility of all of- fices. The local forecast office at Buffalo, New York, January, 1899. The local National Weather Service Office in Tallahassee, FL, present day. 2 Table of Contents Click on description to go directly to the page. 1. What is the National Weather Service?…………………….………………………. 5 Mission Statement 6 Organizational Structure 7 County Warning Areas 8 Weather Forecast Office Staff 10 River Forecast Center Staff 13 NWS Directive System 14 2. Non-Routine Products and Services (watch/warning/advisory descriptions)..…….. 15 Convective Weather 16 Tropical Weather 17 Winter Weather 18 Hydrology 19 Coastal Flood 20 Marine Weather 21 Non-Precipitation 23 Fire Weather 24 Other 25 Statements 25 Other Non-Routine Products 26 Extreme Weather Wording 27 Verification and Performance Goals 28 Impact-Based Decision Support Services 30 Requesting a Spot Fire Weather Forecast 33 Hazardous Materials Emergency Support 34 Interactive Warning Team 37 HazCollect 38 Damage Surveys 40 Storm Data 44 Information Requests 46 3. -

Heat Advisory Guidelines

HACIENDA LA PUENTE UNIFIED SCHOOL DISTRICT OFFICE OF STUDENT AND FAMILY SERVICES 15959 E. GALE AVENUE • CITY OF INDUSTRY, CA 91716 Heat Advisory Precautions for Schools I. GUIDELINES FOR DAILY ACTIVITIES Extreme heat events are characterized by stagnant, warm air masses and consecutive nights with high temperatures. An extreme heat event, or heat wave, is a prolonged period of excessively hot weather, which may be accompanied by high humidity. In times of extreme heat, a heat advisory will be sent from the district office in coordination with the Los Angeles County Office of Education. Otherwise the principal should monitor the heat index on days when heat will be an issue. The heat index is determined by temperature and relative humidity. A. Heat index of 95+ degrees - No outside activities B. Heat index of 90-94 degrees – Limited outside activities 1. Maintain clear focus on supervising students and looking for signs of over-heating 2. Mandatory water breaks every 30 minutes. 3. Mandatory breaks from activities after the water break for 5 to10 minutes in duration. 4. Monitor heat index every 30 minutes C. Heat index of 89 degrees or below – standard protocol REMEMBER: IN TIMES OF EXTREME HEAT, STUDENTS WITH OUTDOOR ACTIVITIES SHOULD BE HYDRATED OFTEN THROUGHOUT THE DAY. II. RATIONALE Our Heat Advisory Precautions are designed to protect students from incurring heat related illnesses or problems. This is a guide for school personnel to use and refer to when making decisions about modifying and/or suspending outdoor activities. The best defense against heat-related conditions is prevention. Staff shall be reminded yearly and in times of extreme heat regarding precautions to take to ensure student safety. -

REFERENCE SHEET for NWS TAUNTON WARNING/ADVISORY THRESHOLDS (Last Updated: March 7, 2017)

REFERENCE SHEET FOR NWS TAUNTON WARNING/ADVISORY THRESHOLDS (Last Updated: March 7, 2017) The following are National Weather Service criteria for issuing Watches/Warnings/Advisories: Watches: 50% confidence of meeting Warning criteria (generally within 36-48+ hours). Advisories and Warnings: 80% confidence in the event occurrence (generally within 24-36 hours). TYPE OF ISSUANCE WHEN ISSUED FOR SOUTHERN NEW ENGLAND WINTER WEATHER ADVISORY More than one predominant hazard Winter weather event having more than one predominant hazard (ie., snow and ice, snow and sleet, or snow, ice & sleet) meeting or exceeding advisory criteria for at least one of the precipitation elements, but remaining below warning criteria. Snow, Ocean Effect Snow, and/or Sleet 3 inches averaged over a forecast zone in 12 hours Snow and Blowing Snow Sustained or frequent gusts of 25 to 34 mph accompanied by falling and blowing snow occasionally reducing visibility to ≤ 1/4 mile for ≥ 3 hours Blowing Snow Widespread or localized blowing snow reducing visibility to ≤ ¼ mile with winds < 35 mph Black Ice A Special Weather Statement will usually be issued when sufficient moisture is expected to cause a thin layer of ice on road surfaces, typically on cloudless nights (“black ice”). At forecaster discretion a formal Winter Weather Advisory may be issued instead. FREEZING RAIN ADVISORY Any accretion of freezing rain or freezing drizzle on road surfaces WIND CHILL ADVISORY Wind chill index between -15°F and -24°F for at least 3 hours using only the sustained wind WINTER STORM WARNING More than one predominant hazard Winter weather event having more than one predominant hazard {ie. -

Weather Vocabulary

SUMMER 2013 SPECIAL EDITION PAGE 1 WEATHER LANGUAGE Common Terms Used in Weather Reports Advisory - A forecast issued by the National damaging winds lasting from 5 to 20 minutes. This may Weather Service to highlight conditions that re- reach tornado intensity. quire caution, but are not thought to be immedi- ately life threatening. Microburst - A small downdraft of air with an outflow di- ameter of less than 2.5 miles with the peak winds lasting Backing Wind - A wind that changes its direction from 2 to 5 minutes. This can effect a planes performance. in a counter clockwise motion. For example, a northwest wind changing to a west wind. Saffir-Simpson Scale - A hurricane intensity scale that relates hurricane damage to wind speeds and central air Cumulonimbus - A dense and vertically developed pressures. Category 1: wind speeds 74-95 m.p.h. cloud that produces thunderstorms. The cloud can Category 2: wind speeds 96-110 m.p.h. bring heavy showers, hail, lightning, high winds and Category 3: wind speeds 111-130 m.p.h. sometimes tornadoes. Category 4: wind speeds 131-155 m.p.h. Cumulus Clouds - Fluffy, mid-level clouds that Category 5: wind speeds over 155 m.p.h. develop in towering shapes and signal fair Severe Thunderstorm - A thunderstorm with winds of 58 weather. Cumulus clouds are a principle cloud type. mph or greater and/or with hail ¾ inch in diameter or lar- ger. Downburst - A strong downward rush of air, which produces a blast of damaging, winds on or close to Severe Thunderstorm Warning - It’s issued to warn the the surface. -

Spearfish Fire Department Policies and Procedures

SPEARFISH FIRE DEPARTMENT POLICIES AND PROCEDURES Page 1 of 5 Volume: Operation Section: 20.00 Number: 20.09 Subject: Weather Watches, Warnings, Advisory’s and Spotter Activation Date Issued: 8 August 2019 Originator: Assistant Chief R. Mathis Rescinds: 28 March 2017 Approval: Assistant Chief R. Mathis I. Purpose This procedure provides guidance for safety and general procedures when responding to Weather Spotter activations. II. SCOPE This policy applies to all personnel. III. DEFINITIONS Winter Storm Watch A Winter Storm Watch is issued when there is the potential for significant and hazardous winter weather within 48 hours. It does not mean that significant and hazardous winter weather will occur...it only means it is possible. Significant and hazardous winter weather is defined as a combination of: 1) 5 inches or more of snow/sleet within a 12-hour period or 7 inches or more of snow/sleet within a 24-hour period AND/OR 2) Enough ice accumulation to cause damage to trees or powerlines AND/OR 3) a life threatening or damaging combination of snow and/or ice accumulation with wind. Blizzard Warning A Blizzard Warning means that the following conditions are occurring or expected within the next 12 to 18 hours. 1) Snow and/or blowing snow reducing visibility to 1/4 mile or less for 3 hours or longer AND 2) Sustained winds of 35 mph or greater or frequent gusts to 35 mph or greater. There is no temperature requirement that must be met to achieve blizzard conditions. Winter Storm Warning A Winter Storm Warning is issued when a significant combination of hazardous winter weather is occurring or imminent. -

Plans for Excessive Heat Emergencies

CONTINGENCY PLAN FOR EXCESSIVE HEAT EMERGENCIES A Supporting Document to the Nevada County Emergency Operations Plan Reviewed Annually Last updated: September 2019 OVERVIEW This is a contingency plan supporting the Nevada County Emergency Operations Plan and the State Contingency Plan for Excessive Heat Emergencies. This plan describes County operations during heat related emergencies and provides guidance for local governments, non-governmental organizations, the private sector and faith-based organizations in the preparation of their heat emergency response plans and other related activities. This plan recognizes three (3) phases of activation. I. Seasonal Readiness a. Seasonal readiness begins annually in May as the warmer months approach; it is the preparedness activities and coordination that takes place prior to receiving a Special Weather Statement from the National Weather Service (NWS). b. Actions are taken as a result of credible predictions by the NWS of prolonged heat or power outages during warmer than normal weather conditions II. Heat Alert (NWS Heat Advisory & NWS Excessive Heat Watch) a. Excessively hot weather with credible weather forecasts of excessively hot weather in the next 24-72 hours. b. These weather conditions include high daytime temperatures, accompanied by night temperatures of 75 degrees or more. c. See Heat Advisory and Excessive Heat Watch definitions below) III. Heat Emergency (NWS Excessive Heat Warning) a. Weather conditions with a heat index of over 105 degrees with NWS Heat Advisories or Warnings or excessively hot weather for more than three days. b. These weather conditions include high daytime temperatures accompanied by night temperatures of 75 degrees or more. c. Proclamation declared by the Nevada County Health Officer of an emergency related to excessive heat.