A Content Analysis of Black Women's Body Image in Television Media

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

January 2019 Programming Highlights – All Programming Subject to Change – Saturday, Jan. 5 Original Series – Season Two Pr

January 2019 Programming Highlights – All programming subject to change – Saturday, Jan. 5 Original Series – Season Two Premiere on Disney Channel and Disney XD Milo Murphy's Law "The Phineas and Ferb Effect" (7:00–8:00 A.M. EST) Milo and his friends, along with their newly discovered neighbors—Phineas, Ferb, Perry the Platypus, Candace, Isabella, Baljeet and Buford—must work together to overcome Murphy's Law in order to stop a pistachio invasion. *Guest stars include Ashley Tisdale ("High School Musical") as Candace, Alyson Stoner ("Camp Rock") as Isabella, Vincent Martella ("Everybody Hates Chris") as Phineas, David Errigo Jr. ("Yu- Gi-Oh! Arc-V") as Ferb, Dee Bradley Baker ("Mickey and the Roadster Racers") as Perry the Platypus, Maulik Pancholy ("30 Rock") as Baljeet and Bobby Gaylor ("The Nightly Show with Larry Wilmore") as Buford. TV-Y7 Sunday, Jan. 6 Original Series – Episode Premiere on Disney XD Marvel's Avengers: Black Panther's Quest "Vibranium Curtain Part One" (9:00–9:30 P.M. EST) Black Panther devises a plan to get the information he needs, but he isn't the only one with a plan. TV-Y7 FV Original Series – Episode Premiere on Disney XD Marvel's Avengers: Black Panther's Quest "Vibranium Curtain Part Two" (9:30–10:00 P.M. EST) Captured by his enemies, Black Panther must break out of prison with an unlikely ally. TV-Y7 FV Friday, Jan. 11 Original Series – Episode Premiere on Disney Channel Vampirina "The Woodsie Way/TNN" (10:30–11:00 A.M. EST) "The Woodsie Way" – Vee and her friends go on their first hiking trip with the Woodchuck Woodsies. -

ANNUAL REPORT 2015 16 A70 TV Acad Ad.Qxp Layout 1 7/8/16 11:43 AM Page 1

ANNUAL REPORT 2015 16_A70_TV_Acad_Ad.qxp_Layout 1 7/8/16 11:43 AM Page 1 PROUD MEMBER OF »CBS THE TELEVISION ACADEMY 2 ©2016 CBS Broadcasting Inc. MESSAGE FROM THE CHAIRMAN AND CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER AS THE QUANTITY AND QUALITY OF CONTENT HAVE INCREASED in what is widely regarded as television’s second Golden Age, so have employment opportunities for the talented men and women who create that programming. And as our industry, and the content we produce, have become more relevant, so has the relevance of the Television Academy increased as an essential resource for television professionals. In 2015, this was reflected in the steady rise in our membership — surpassing 20,000 for the first time in our history — as well as the expanding slate of Academy-sponsored activities and the heightened attention paid to such high-profile events as the Television Academy Honors and, of course, the Creative Arts Awards and the Emmy Awards. Navigating an industry in the midst of such profound change is both exciting and, at times, a bit daunting. Reimagined models of production and distribution — along with technological innovations and the emergence of new over-the-top platforms — have led to a seemingly endless surge of creativity, and an array of viewing options. As the leading membership organization for television professionals and home to the industry’s most prestigious award, the Academy is committed to remaining at the vanguard of all aspects of television. Toward that end, we are always evaluating our own practices in order to stay ahead of industry changes, and we are proud to guide the conversation for television’s future generations. -

Television Academy Awards

2019 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot Outstanding Comedy Series A.P. Bio Abby's After Life American Housewife American Vandal Arrested Development Atypical Ballers Barry Better Things The Big Bang Theory The Bisexual Black Monday black-ish Bless This Mess Boomerang Broad City Brockmire Brooklyn Nine-Nine Camping Casual Catastrophe Champaign ILL Cobra Kai The Conners The Cool Kids Corporate Crashing Crazy Ex-Girlfriend Dead To Me Detroiters Easy Fam Fleabag Forever Fresh Off The Boat Friends From College Future Man Get Shorty GLOW The Goldbergs The Good Place Grace And Frankie grown-ish The Guest Book Happy! High Maintenance Huge In France I’m Sorry Insatiable Insecure It's Always Sunny in Philadelphia Jane The Virgin Kidding The Kids Are Alright The Kominsky Method Last Man Standing The Last O.G. Life In Pieces Loudermilk Lunatics Man With A Plan The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel Modern Family Mom Mr Inbetween Murphy Brown The Neighborhood No Activity Now Apocalypse On My Block One Day At A Time The Other Two PEN15 Queen America Ramy The Ranch Rel Russian Doll Sally4Ever Santa Clarita Diet Schitt's Creek Schooled Shameless She's Gotta Have It Shrill Sideswiped Single Parents SMILF Speechless Splitting Up Together Stan Against Evil Superstore Tacoma FD The Tick Trial & Error Turn Up Charlie Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt Veep Vida Wayne Weird City What We Do in the Shadows Will & Grace You Me Her You're the Worst Young Sheldon Younger End of Category Outstanding Drama Series The Affair All American American Gods American Horror Story: Apocalypse American Soul Arrow Berlin Station Better Call Saul Billions Black Lightning Black Summer The Blacklist Blindspot Blue Bloods Bodyguard The Bold Type Bosch Bull Chambers Charmed The Chi Chicago Fire Chicago Med Chicago P.D. -

A VIRTUAL CABARET EVENT in Support Of

A VIRTUAL CABARET BENEFITING THE NATIONAL BREAST CANCER COALITION FUND FROM THE HOSTS OF AND THE NEWGala YORK Sunday, December 6, 2020 5 p.m. PT / 8 p.m. ET A LETTER FROM FRAN Dear Friends, Welcome to our first-everVirtual Cabaret Event and an evening of talented performances and tantalizing fun, all for a great cause. This year marks the 20th Anniversary of our Les Girls Cabaret and the 25th Anniversary of our NY Gala, and these two special events have sustained the National Breast Cancer Coalition (NBCC), year after year. When the pandemic hit, I began to wonder if either event would happen. But we found a way. Thanks to the extraordinary efforts of our Event Committee, the encouragement of our sponsors, the personal commitment of our hosts and performers, and the imagination of our production team, we are able to combine both events and once again offer a one-of-a-kind, fantastic evening. We are forever grateful to all of them. Since 1991, NBCC has been at the vanguard of the breast cancer movement, elevating breast cancer to an issue of national significance. NBCC brought about a federal research program that has awarded over $3.75 billion in research grants. We empower women and men, through education and training, to become a unified voice to save lives. And through our Artemis Project®, we lead a collaboration of exceptional scientists and dedicated advocates who focus on research to prevent women and men from getting breast cancer in the first place and stop it from metastasizing and taking lives. -

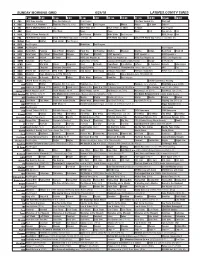

Sunday Morning Grid 6/24/18 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 6/24/18 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program PGA Tour Special (N) PGA Golf 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) NBC4 News Paid Program House House 1st Look Extra Å 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 KTLA 5 News at 10am In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News News News Paid Eye on L.A. Paid 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Mike Webb Paid Program REAL-Diego Paid 11 FOX FIFA World Cup Today 2018 FIFA World Cup Japan vs Senegal. (N) FIFA World Cup Today 2018 FIFA World Cup Poland vs Colombia. (N) 13 MyNet Paid Matter Fred Jordan Paid Program 18 KSCI Paid Program Buddhism Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Paint With Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Kitchen Mexican Martha Belton Real Food Food 50 28 KCET Zula Patrol Zula Patrol Mixed Nutz Edisons Kid Stew Biz Kid$ KCET Special Å KCET Special Å KCET Special Å 30 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Paid NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å 34 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Como Dice el Dicho La casa de mi padre (2008, Drama) Nosotr. Al Punto (N) 40 KTBN James Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Jeffress K. -

Penrose Foundation Donates Two Suburban Buildinss $10,« » to Aid Nursing Study to Be Blessod Next Week DENVER Cathaic

, r Penrose Foundation Donates Two Suburban BuildinSS $10,« » to Aid Nursing Study To Be Blessod Next Week At a meeting early this week at the home of Arch 'The dedication of St. An bishop Urban J. Vehr of Den thony’s church-hall,„ West- ver, Sister M. Cyril, director wood, and the blessing of the of the Seton School of Nurs rectory of St. Anne’s shrine, ing, Colorado Springs, an Arvada, are scheduled next nounced a gift of $10,000 from week. Archbishop Urban J. the Spencer Penrose founda Vehr will officiate at the for tion to help finance the first mer Wednesday, Sept. 29, and years of the new nursing edu at the latter the following*day. cation program inaugurated After the dedication of St. An this fall at Loretto Heights thony’s, a Solemn Mass, ■ eoram Archiepiacopo, will be sung at college 10:30 by the Rev, John Doherty of This program is operated in con Lakewood. The assistant priest junction with St. Anthony’s School at the Archbishop’s throne ■will of Nursing and Mercy ^chool of be the Very Rev. Joseph P. Nursing in Denver, ancr with the O’Heron of Englewood; deacon, Seton School of Nursing at Colo the Rev. Francis Wagmer of rado Springs. Mrs. Spencer Pen Paonia; subdeacon, the Rev. Fredi- L rose was largely instrumental in erick McCallin of Littleton; securing this gift from the foun deacons of honor, the Very RcV. dation in memory of her late hus Gregory Smith of St. Francis de band. The program has accord Sales’ and the Rev. -

Andrew A. Robinson Elementary Every Student in Grades K-5 At

Black History Timeline Andrew A. Robinson Elementary Every student in grades K-5 at A.R.E. will complete a Black History Timeline at home based on the guidelines in this packet. Students will select a famous African- American in the category for their grade level, complete a timeline at home, and submit it to your ELA teacher on the assigned due date for a grade. The final project is due to your Language Arts teacher on Tuesday, February 25, 2021. Being that this is an at home project, your child will not be given time at school to research, plan, or complete this project. Please help your child in his/her efforts to have the project follow the requirements and handed in on time. PLEASE NOTE: This project will count as a test grade in Language Arts and Social Studies. One project per homeroom class will be selected to be featured on the A.R.E. Facebook page. Let’s hope it’s yours!! Black History Timeline Make an illustrated timeline (10 or more entries on the timeline) showing important events from the life of the person you are doing your Black History Project on. This project should be completed on a sheet of poster board. Underneath each illustration on the timeline, please create a detailed caption about what is in the illustration and the date in which the event occurred. *You must include: • A minimum of 10 entries on the timeline put in chronological order. • At least 5 entries should include an illustrated picture and detailed caption. • You must include at least one event on each of the following topics: the person’s date of birth, education, what made this figure important in African American history and their life’s accomplishment (s). -

Big Savings on Your

$1 Weekend Edition Saturday, Dec. 12, 2015 Returning to Scenes of Destruction Taking Stock After Days of Flooding in Lewis County and Beyond / Inside Pete Caster / [email protected] A truck heads toward the state Route 131 bridge through loodwaters near the Cowlitz River in Randle Thursday morning. Washington State Department of Transportation plows moved a majority of the water away from both the north and south side of the bridge on Thursday in order for people to pass over the bridge and return to devastated property and homes. The Chronicle, Serving The Greater Cispus River Cowlitz River Deaths Lewis County Area Since 1889 At Least Cabins Masters, Ezmae Rose, 16 Follow Us on Twitter days old, Centralia @chronline One Ripped From Toland, Milton Scott, 52, Couple Foundations Centralia Find Us on Facebook Will Leave After Titanic Ahrens, Richard, 58, www.facebook.com/ Chehalis thecentraliachronicle East End Log Jam Golden, Sheila, 53, for Good Break Packwood / Main 4 / Main 3 BIG SAVINGS ON YOUR FAVORITE ACTIVE WEAR! CH548903co.sw NIKE CLEARANCE STORE • UNDER ARMOUR • HELLY HANSEN • EDDIE BAUER OUTLET 360-736-3900 • WWW.CENTRALIAOUTLETS.COM • I-5 EXIT 82 • BOTH SIDES • CENTRALIA Main 2 The Chronicle, Centralia/Chehalis, Wash., Saturday, Dec. 12, 2015˚ PAGE TWO News Daily Outtake: Floodwaters Recede, Snow Returns of the Weird Kansas Deputies Police Follow Liquid Confront Nude Oregon Left By Car to Arrest Man Taking Pictures Shooting Suspect NEWTON, Kan. (AP) — LAS CRUCES, N.M. (AP) — Kansas authorities say an Or- Las Cruces police investigating a egon man was urged to head shootout outside a pub arrested home after he was spotted tak- a man after following fluid that ing pictures of a wheat field leaked from a vehicle. -

2019 Annual Report

PURPOSE Promise Progress 2 0 1 9 E T F A n n ua l R ep ort LEADERSHIP National Board of Trustees Timothy Allen McDonald Deborah Voigt Dear Friends and Supporters, iTheatrics, Founder and CEO Award-winning opera soprano Matt Conover, Chair New York, NY Disney Parks Live Entertainment, Vice Advisory Board The stories of ETF in 2019 are the stories of how theatre has shaped all of us: kids looking President of Disneyland Entertainment Megan Tulac Phillips Sarah Jane Arnegger forward to going to school to sing and dance, individuals with soaring confidence after Anaheim, CA McKinsey & Company, Head of iHeartRadio Broadway, Director progressive accomplishments on stage, theatre having a therapeutic impact by bonding Marketing and Communications, New York, NY Hunter Bell, Vice Chair Enterprise Agility a group of students as a family. Tony-nominated playwright, EdTA San Francisco, CA Aretta Baumgartner Board of Directors Center for Puppetry Arts, Education What makes ETF unique is that we are funding these kinds of experiences in New York, NY John Prignano Director communities which otherwise would not be able to offer them: cities recovering from Music Theatre International, COO Atlanta, GA Nancy Aborn Duffy, Secretary and Director of Education and disasters, programs with no budgets for teacher professional development or student Educator, Former Broadway Licensing Development Dori Berinstein Company Owner festival participation, and schools who previously had no theatre at all. New York, NY Dramatic Forces, Producer New York, NY New York, NY Kim Rogers This was a momentous year as we expanded grant programs for schools and established James A. -

Mini-THON Raises Over $62,000 FTK

The Campanile Mount Saint Joseph Academy Volume LVIII, Number 3 February 2018 Mini-THON raises over $62,000 FTK By Maddie Feeney ’18 reach our goal of $50,000, but the as well as to “stall” their fourth “I am so happy to have had the op- DiSisto commented, “It was amount we raised up at 10 p.m. block class. portunity to come back to speak! truly amazing to be a part of On Friday, Feb. 16, at Mount’s was a true showing of how much However, the night was about It makes me an extremely proud something that special.” 5th Annual Mini-THON, over our school community came to- so much more than the money alumna to know that so many For seniors, their very last 200 students danced for the kids, gether for this cause.” raised, especially to the four students are supporting these big Mini-THON was especially poi- raising a total of $62,478.04. In the months leading up to speakers: Lauren Buben ’13, events to raise funds and aware- gnant. The final tally surpassed the Mini-THON, fundraisers held at Caroline Free ’16, Villa Maria ness for pediatric cancer.” “Seeing Mini-THON grow goal of $50,000 and nearly dou- PJ Whelihan’s, CycleBar, Rita’s sophomore Izzi DeSimone and Villa Maria’s DeSimone said, over my four years has been re- bled last year’s total of $33, 476. and Rise Barre helped propel Plymouth Whitemarsh freshman “The Mount’s Mini-THON was markable. My last one was the Senior co-chair Abby fundraising efforts. -

ABC Catalog 2018

8 Little Planets Baby Loves Hello, World! BABIES Chris Ferrie, Gravity! Dinosaurs illustrated by Ruth Spiro, Jill McDonald Lizzy Doyle illustrated by The Hello World! Irene Chan To the tune of Ten Little series introduces Monkeys Jumping on the Baby Loves Gravity! is a a board book that Bed comes a new bedtime clever board book that teaches toddlers all & story from bestselling explores the ups and downs about Triceratops, author Chris Ferrie that’s of gravity. When baby drops food from a high chair, why Stegosaurus, T-rex, TODDLERS sure to get little ones excited about the solar system does it fall? Ages 0-3 (9781580898362) Charlesbridge (BB) and many more using while learning new facts about each planet! Ages 0-3 $8.99 E-book (9781632897251) colors, shapes, sizes, and (9781492671244) Sourcebooks Jabberwocky (BB) $10.99 super-simple facts. Ages 0-3 (9781524719340) E-book (9781492674009) Black Bird Doubleday Books for Young Readers (BB) $7.99 Yellow Sun Baby Loves Coding! Steve Light I Am Little Ruth Spiro, Fish! A Finger illustrated by From the creator of Have You Puppet Book Irene Chan Seen My Dragon? comes an exploration of color that Lucy Cousins Accurate enough to 3 AGES 0 TO truly soars. Ages 0-3 With the wiggle of a satisfy a coding (9780763690670) ★ K, SLJ finger, readers bring expert, yet simple Candlewick (BB) $7.99 Little Fish to life as he enough for baby, this pops through every spread of this adorable puppet book. clever board book Ages 0-3 (9781536200232) Candlewick (BB) $12.99 showcases the use of logic, sequence, and Bye-Bye! patterns to solve problems. -

'Greenleaf' with Post-Finale Special

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE August 10, 2020 OWN SAYS FAREWELL TO HIT MEGACHURCH DRAMA ‘GREENLEAF’ WITH POST-FINALE SPECIAL Cast Reunites One Last Time for a Memorable Look Back at the Groundbreaking Drama Series about Faith and Family Tuesday, August 11 at 10:00 p.m. ET/PT “Greenleaf” Is the Most Watched Show by African American Viewers on All of Television LOS ANGELES – The stars of OWN’s hit megachurch drama “Greenleaf,” the critically- acclaimed series from Lionsgate, award-winning writer/executive producer Craig Wright (“Lost,” “Six Feet Under”), and executive producers Clement Virgo (“Empire”), Kriss Turner Towner (“Black Monday”) and Oprah Winfrey, will take a look back at the beloved show in a one-hour special airing Tuesday, August 11 at 10:00 p.m. ET/PT, immediately following the series finale. The special will feature “Greenleaf” cast including Merle Dandridge, Keith David, Lynn Whitfield, Lamman Rucker, and Deborah Joy Winans sharing favorite moments from the past five seasons and answering questions from the devoted fans. The penultimate (8/4/20) episode of “Greenleaf” garnered a season-high 2,117,000 viewers and continued to be Tuesday night’s #1 cable telecast among Women 25-54 and W18-49. During its current season, “Greenleaf” is the #1 original series across broadcast and cable for African American women, households and total viewers. Clip from final episode of “Greenleaf” airing Tuesday, August 11 at 9p.m. ET/PT: https://youtu.be/mkUbGgNzSLU About Greenleaf “Greenleaf” has garnered ten NAACP Image Award nominations, including wins for Outstanding Drama Series in 2020, and Outstanding Supporting Actress in a Drama Series in 2019 and 2020 (Lynn Whitfield).