Transcript for the Future of the COPPA Rule: an FTC Workshop

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![[E:] 09 a Second Face.Mp3=2129222 ACDC Whole Lotta Rosie (Rare Live](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7220/e-09-a-second-face-mp3-2129222-acdc-whole-lotta-rosie-rare-live-217220.webp)

[E:] 09 a Second Face.Mp3=2129222 ACDC Whole Lotta Rosie (Rare Live

mTad [E:] 09 A Second face.mp3=2129222 ACDC Whole Lotta Rosie (rare live Bon Scott).mp3=4874280 Damnation of Adam Blessing - Second Damnation - 05 - Back to the River.mp3=5113856 Eddie Van Halen - Eruption (live, rare).mp3=2748544 metallica - CreepingDeath (live).mp3=4129152 [E:\1959 - Miles Davis - Kind Of Blue] 01 So What.mp3=13560814 02 Freddie Freeloader.mp3=14138851 03 Blue In Green.mp3=8102685 04 All Blues.mp3=16674264 05 Flamenco Sketches.mp3=13561792 06 Flamenco Sketches (Alternate Take).mp3=13707024 B000002ADT.01.LZZZZZZZ.jpg=19294 Thumbs.db=5632 [E:\1965 - The Yardbirds & Sonny Boy Williamson] 01 - Bye Bye Bird.mp3=2689034 02 - Mister Downchild.mp3=4091914 03 - 23 Hours Too Long.mp3=5113866 04 - Out Of The Water Coast.mp3=3123210 05 - Baby Don't Worry.mp3=4472842 06 - Pontiac Blues.mp3=3864586 07 - Take It Easy Baby (Ver 1).mp3=4153354 08 - I Don't Care No More.mp3=3166218 09 - Do The Weston.mp3=4065290 10 - The River Rhine.mp3=5095434 11 - A Lost Care.mp3=2060298 12 - Western Arizona.mp3=2924554 13 - Take It Easy Baby (Ver 2).mp3=5455882 14 - Slow Walk.mp3=1058826 15 - Highway 69.mp3=3102730 albumart_large.jpg=11186 [E:\1971 Nazareth] 01 - Witchdoctor Woman.mp3=3994574 02 - Dear John.mp3=3659789 03 - Empty Arms, Empty Heart.mp3=3137758 04 - I Had A Dream.mp3=3255194 05 - Red Light Lady.mp3=5769636 06 - Fat Man.mp3=3292392 07 - Country Girl.mp3=3933959 08 - Morning Dew.mp3=6829163 09 - The King Is Dead.mp3=4603112 10 - Friends (B-side).mp3=3289466 11 - Spinning Top (alternate edit).mp3=2700144 12 - Dear John (alternate edit).mp3=2628673 -

September 2013

PPhotoshotos bbyy KKimim RRuthuth aandnd DestineeDestinee ReaRea " Health Care Taxes Liberty rttiioO Economy War HVxyq!&C q Sqqyhq % & C '6xxpsRRxxgGu u$#"e Education in , ColinCol difer Stan irit. rew Standiferor sp , And seni wers,wers Andreheir n Bo ing t Bail-Out Social Sea howingw their senior spirit. ohn, ett s ettijohn,ettij Sean Wil lBo bie P eron , RobbieRob P Cam rphy , and MurphyMu ford,ford and Cameron Willett sho E trick ckelkel rs PatrickPa Sha enio Jake Shac SSeniorsr ald, tzGe SSeniors FFitzGerald,i Jak eni ors sshowho theirAlexAl espiritx Rager at the and fir Marissa P w th Ra S e e ge ir sp r an irit a d Ma t th riss e fir a P sstt ppep assemblyenceence ep a ssem bly. Taxes Liber TThehe MMarchingarching BBulldogulldog BrigadeBrigade putsputs onon theirtheir half-timehalf-time show.show. E TThehe BBulldogulldog cheerleaderscheerleaders ccheerheer tthehe bboysoys Pq qiuq oonn ttoo theirtheir ffourthourth vvictoryictory ooff tthehe sseason.eason. Taxes Liber RRHSHS ccheerleadersheerleaders ppreformreform Economy Wa dduringuring thethe fristfrist ppepep assasseembly.mbly. Education Va SSchoochool Social Securit TradeWho is Educaright for America? Bail-Out SocialaPages Security 12 & 13 $ SSpiritpirit S9PT Health Care Taxes Liberty Meditation practice tthehe H.A.B.I.T ooff SSeptembereptember ! The (health and academics boosted in teens) 22008008 As I sat at my computer screen, agement of one’s thoughts that is smoking and drinking. In a way, BBeste s designed to bring serenity, clarity meditation is the “reset button” for t Beat : I was faced with a blank, white MMontho n t and bliss in every aspect of life. -

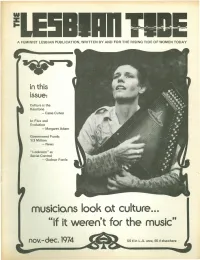

"If It Weren't for the Music"

III Z ~ A FEMINIST LESBIAN PUBLICATION, WRITTEN BY AND FOR THE RISING TIDE OF WOMEN TODAY in this issue: Culture is the Keystone - CasseCuIver In Flux and Evolution - Margaret Adam Government Funds 1/3 Million - News "Looksism" as Social Control - Gudrun Fonta rnoslclons look or culture... "if it weren't for the music" nov.-dec.1974 50 ¢ in L.A. area, 65 ¢ elsewhere 'Ohe THE TIDE COLLECTIVE ADVERTISING VOLUME 4, NUMBER 4 Jeanne Cordova CIRCULATION TABLE OF CONTENTS Barbara Gehrke Dakota EDITORIAL Jeanne Cordova ANNOUNCEr~ENTS 18 Annie Doczi Janie Elven ART! CLES Gudrun Fonfa Kathy Moonstone 3 An Electric Microcosm RO(ji Rubyfruit Lesbian Mothers Fighting Back 7 Robin Morgan; Sisterhood, Inc. Dead 7 Terre Skill-sharing: I Can't Stand It 9 Letter to a Friend 11 FiNANCE, COLLECTIONS & FUNDRAISING Innerview with Arlene Raven 13 Rape Victim Condemned 10 A Lesbian Tide EnNobles Boston 18 Barbara Gehrke CLASSIFIED ADS 19 PHOTOGRAPHY 20 CROSSCURRENTS Kathy Moonstone FROl1 US 8 Sandy P. LETTERS 8 PRODUCTION POETRY Helen H. Ri tua 1 1 6 Sandy P. A Ta 1e in Time 11 Tyler Poem 26 An Anniversary Issue 30 REVIEWS Lavender Jane Loves Women 12 Politics of Linguistics 15 New York Coordinator: Karla Jay ROUNDTABLE: Musicians Look at Culture Culture is the Keystone 4 Cover Design by Sandy P. In Flux and Evolution 4 Keeping Our Art Alive 5 How I See It 5 Photography Credits: New Haven Women's Liberation Rock Band 6 pages 4 & 5, Lynda Koolish; cover, Nina S.; pages 26 & 29, Jeb Graphic Credits: page 17, Rogi Rubyfruit; page 39, Julie H. -

Dean Martin I'm Not the Marrying Kind Mp3, Flac, Wma

Dean Martin I'm Not The Marrying Kind mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Jazz / Pop Album: I'm Not The Marrying Kind Country: France Released: 1966 Style: Vocal, Easy Listening MP3 version RAR size: 1911 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1581 mb WMA version RAR size: 1869 mb Rating: 4.4 Votes: 452 Other Formats: MPC FLAC DXD WAV AC3 DTS VQF Tracklist Hide Credits I'm Not The Marrying Kind A 2:03 Written-By – Greenfield*, Schifrin* (Open Up The Door) Let The Good Times In B 2:57 Written-By – Torok*, Redd* Companies, etc. Distributed By – Disques Vogue Credits Arranged By – Bill Justis Producer – Jimmy Bowen Notes French Juke-Box promo Barcode and Other Identifiers Rights Society: BIEM Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year 0538 Dean Martin I'm Not The Marrying Kind (7") Reprise Records 0538 US 1966 I'm Not The Marrying Kind / Let 0538 Dean Martin The Good Times In (7", Single, Reprise Records 0538 US 1966 Promo) 0538 Dean Martin I'm Not The Marrying Kind (7") Reprise Records 0538 Lebanon 1966 Let The Good Times In / I'm Not R 0538 Dean Martin Reprise Records R 0538 Norway 1967 The Marrying Kind (7") I'm Not The Marrying Kind (7", 0538 Dean Martin Reprise Records 0538 Canada 1966 Single) Related Music albums to I'm Not The Marrying Kind by Dean Martin Dean Martin - I Will Dean Martin - In The Chapel In The Moonlight Dean Martin - Come Running Back / Bouquet Of Roses Dean Martin - The Dean Martin TV Show & Dean Martin Sings Songs From "The Silencers" Marrying M - Marrying Maiden- It's a beautiful day Dean Martin - A Million And One / Shades Dean Martin With The Jimmy Bowen Orchestra & Chorus - Georgia Sunshine Dean Martin - Dean "Tex" Martin Rides Again Dean Martin - Somewhere There's A Someone Dean Martin - A Personal Message From Dean Martin. -

Click on This Link

The Australian Songwriter Issue 111, December 2015 First published 1979 The Magazine of The Australian Songwriters Association Inc. 1 In This Edition: On the Cover of the ASA: Johnny Young and Karen Guymer Chairman’s Message Editor’s Message 2015 National Songwriting Awards Photos Johnny Young: 2015 Inductee into The Australian Songwriters Hall of Fame Karen Guymer : 2015 APRA/ASA Songwriter of the Year George Begbie: 2015 Winner of The Rudy Brandsma Award 2015 Rudy Brandsma Award Nominees 2015 Australian Songwriting Contest: Top 30 Category Winners Rick Hart: A 2015 Retrospective Wax Lyrical Roundup 2015 ASA Regional Co-Ordinators Conference Interview: The Wayward Henrys ASA Regional Co-Ordinator (TAS): Matt Sertori 2015 In Memoriam Members News and Information Sponsors Profiles The Load Out Official Sponsors of the Australian Songwriting Contest About Us: o Aims of the ASA o History of the Association o Contact Us o Patron o Life Members o Directors o Regional Co-Ordinators o APRA/ASA Songwriter of the Year o Rudy Brandsma Award Winner o PPCA Live Performance Award Winner o Australian Songwriters Hall of Fame o Australian Songwriting Contest Winners 2 Chairman’s Message To all our valued ASA Members, Wow! I am still recovering from the 2015 National Songwriting Awards evening. Every year just seems to get bigger and better, and this one is no exception. Congratulations to the songwriters who are mentioned in this e-Magazine, and to all who participated in the Contest. Without doubt the quality of the songs improves every year, and so many of our Members contributed to make our 2015 Competition the best yet. -

RCA Victor 12 Inch Popular Series LPM/LSP 3700-3999

RCA Discography Part 12 - By David Edwards, Mike Callahan, and Patrice Eyries. © 2018 by Mike Callahan RCA Victor 12 Inch Popular Series LPM/LSP 3700-3999 LPM/LSP 3700 – Norma Jean Sings Porter Wagoner – Norma Jean [1967] Dooley/Eat, Drink And Be Merry/Country Music Has Gone To Town/Misery Loves Company/Company's Comin'/I've Enjoyed As Much Of This As I Can Stand/Howdy Neighbor, Howdy/I Just Came To Smell The Flowers/A Satisfied Mind/If Jesus Came To Your House/Your Old Love Letters/I Thought I Heard You Calling My Name LPM/LSP 3701 – It Ain’t necessarily Square – Homer and Jethro [1967] Call Me/Lil' Darlin'/Broadway/More/Cute/Liza/The Shadow Of Your Smile/The Sweetest Sounds/Shiny Stockings/Satin Doll/Take The "A" Train LPM/LSP 3702 – Spinout (Soundtrack) – Elvis Presley [1966] Stop, Look And Listen/Adam And Evil/All That I Am/Never Say Yes/Am I Ready/Beach Shack/Spinout/Smorgasbord/I'll Be Back/Tomorrow Is A Long Time/Down In The Alley/I'll Remember You LPM/LSP 3703 – In Gospel Country – Statesmen Quartet [1967] Brighten The Corner Where You Are/Give Me Light/When You've Really Met The Lord/Just Over In The Glory-Land/Grace For Every Need/That Silver-Haired Daddy Of Mine/Where The Milk And Honey Flow/In Jesus' Name, I Will/Watching You/No More/Heaven Is Where You Belong/I Told My Lord LPM/LSP 3704 – Woman, Let Me Sing You a Song – Vernon Oxford [1967] Watermelon Time In Georgia/Woman, Let Me Sing You A Song/Field Of Flowers/Stone By Stone/Let's Take A Cold Shower/Hide/Baby Sister/Goin' Home/Behind Every Good Man There's A Woman/Roll -

October 1995

RICHIE HAYWARD Little Feat is back—with a new line-up, a new album, and a newly invigorated Richie Hayward behind the kit. An up-close look at one of our most esteemed practitioners. • Robyn Flans and William F. Miller 38 HIGHLIGHTS OF MD's FESTIVAL WEEKEND '95 Festival number eight: Steve Smith, Peter Erskine, Stephen Perkins, Mike Portnoy, Gregg Bissonette, Kenwood Dennard, Rayford Griffin, Alan White. What's that? Couldn't make it? Lucky for you, our flash bulbs were working overtime! 51 FERGAL LAWLER The Cranberries' name might suggest pretty, polite pop, but Fergal Lawler's drumming adds a burning passion that boosts this very hot band to fiery heights. • Ken Micallef 70 Volume 19, Number 10 Cover photo by Aldo Mauro Columns EDUCATION NEWS EQUIPMENT 82 ROCK 10 UPDATE 24 NEW AND PERSPECTIVES Chris Gorman of Belly, NOTABLE Bruford's Ostinato Dawn Richardson, Challenge jazzer Bob Gullotti, and 30 PRODUCT BY ROB LEYTHAM Tony McCarroll of Oasis, CLOSE-UP plus News Gibraltar Hardware 86 ROCK 'N' BY RICK MATTINGLY JAZZ CLINIC 142 INDUSTRY The "3 Hands" Concept HAPPENINGS BY JON BELCHER 88 DRUM SOLOIST DEPARTMENTS Paul Motian: "Israel" TRANSCRIBED BY STEVE KORN 4 EDITOR'S OVERVIEW 90 STRICTLY TECHNIQUE 6 READERS' 33 Specialty Bass Syncopation Accent PLATFORM Drum Beaters Exercises: Part 2 BY RICK VAN HORN BY DAVE HAMMOND 14 ASK A PRO 136 SHOP TALK 82 IN THE STUDIO David Garibaldi, Max A Non-Slip Tip The Drummer's Weinberg, and Jim Keltner BY J.J. VAN OLDENMARK Studio Survival Guide: Part 7, Multitrack 20 IT'S Recording QUESTIONABLE BY MARK -

The Transnational Asian Studio System: Cinema, Nation-State, and Globalization In

The Transnational Asian Studio System: Cinema, Nation-State, and Globalization in Cold War Asia by Sangjoon Lee A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Cinema Studies New York University May, 2011 _______________________ Zhang Zhen UMI Number: 3464660 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent on the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI 3464660 Copyright 2011 by ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This edition of the work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, MI 48106 - 1346 ⓒ Sangjoon Lee All Right Reserved, 2011 DEDICATION This dissertation is dedicated to my father, Lee Eui-choon, and my mother, Kim Sung-ki, for their love and support. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This dissertation would not have been possible without the generous support and encouragement of my committee members and fellow colleagues at NYU. My deepest debts are to my dissertation advisor; Professor Zhang Zhen has provided me through intellectual inspirations and guidance, a debt that can never be repaid. Professor Zhang is the best advisor anyone could ask for and her influence on me and this project cannot be measured. This dissertation owes the most to her. I have been extremely fortunate to have the support of another distinguished film scholar, Professor Yoshimoto Mitsuhiro, who has influenced my graduate studies since the first seminar I took at NYU. -

News Release

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE - April 7, 2020 Press Contact: Maggie Stapleton, Jensen Artists 646.536.7864 x2 [email protected] American Composers Orchestra Announces Connecting ACO Community A new solo commissioning initiative in response to the COVID-19 crisis with online world premieres beginning Sunday, April 19, 2020 at 5pm EST on Zoom $5 tickets available through Eventbrite | More information at https://bit.ly/ACOConnect New York, NY – In response to the impacts of COVID-19 on composers and performers, American Composers Orchestra announces Connecting ACO Community, a new initiative to commission short works for solo instrument or voice. Each composer will receive $500 to write the work, and each performer will receive $500 to perform the work, with the rights to stream for six months. With these seven premieres, ACO aims to support artists who need financial assistance; to create new work that will live beyond this crisis; and to provide virtual, interactive performances to ACO’s supporters and the general public. Premieres of the new works will take place each Sunday at 5pm EST, beginning Sunday, April 19, 2020 at 5pm EST with violinist Miranda Cuckson performing a new work by Ethan Iverson, hosted on Zoom. Ticketholders will receive a private link to join the performance, and all of the proceeds from the ticket sales will go solely to fund artists involved in this project. If the $5 entrance fee poses a barrier to participation, interested listeners will be asked to fill out an anonymous form at https://bit.ly/ACOConnectComp or email Aiden Feltkamp at [email protected] to request a fee waiver. -

Songs by Title

Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist - Human Metallica (I Hate) Everything About You Three Days Grace "Adagio" From The New World Symphony Antonín Dvorák (I Just) Died In Your Arms Cutting Crew "Ah Hello...You Make Trouble For Me?" Broadway (I Know) I'm Losing You The Temptations "All Right, Let's Start Those Trucks"/Honey Bun Broadway (I Love You) For Sentimental Reasons Nat King Cole (Reprise) (I Still Long To Hold You ) Now And Then Reba McEntire "C" Is For Cookie Kids - Sesame Street (I Wanna Give You) Devotion Nomad Feat. MC "H.I.S." Slacks (Radio Spot) Jay And The Mikee Freedom Americans Nomad Featuring MC "Heart Wounds" No. 1 From "Elegiac Melodies", Op. 34 Grieg Mikee Freedom "Hello, Is That A New American Song?" Broadway (I Want To Take You) Higher Sly Stone "Heroes" David Bowie (If You Want It) Do It Yourself (12'') Gloria Gaynor "Heroes" (Single Version) David Bowie (If You're Not In It For Love) I'm Outta Here! Shania Twain "It Is My Great Pleasure To Bring You Our Skipper" Broadway (I'll Be Glad When You're Dead) You Rascal, You Louis Armstrong "One Waits So Long For What Is Good" Broadway (I'll Be With You) In Apple Blossom Time Z:\MUSIC\Andrews "Say, Is That A Boar's Tooth Bracelet On Your Wrist?" Broadway Sisters With The Glenn Miller Orchestra "So Tell Us Nellie, What Did Old Ironbelly Want?" Broadway "So When You Joined The Navy" Broadway (I'll Give You) Money Peter Frampton "Spring" From The Four Seasons Vivaldi (I'm Always Touched By Your) Presence Dear Blondie "Summer" - Finale From The Four Seasons Antonio Vivaldi (I'm Getting) Corns For My Country Z:\MUSIC\Andrews Sisters With The Glenn "Surprise" Symphony No. -

Dean Martin at Ease with Dean Mp3, Flac, Wma

Dean Martin At Ease With Dean mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Jazz Album: At Ease With Dean Country: UK Released: 1966 MP3 version RAR size: 1126 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1429 mb WMA version RAR size: 1708 mb Rating: 4.1 Votes: 915 Other Formats: MMF AHX WAV AUD DMF AAC DTS Tracklist A1 If I Had You A2 What Can I Sa After I'm Sorry? A3 The One I Love A4 S'posin A5 It's The Talk Of Town B1 Baby Won't You Come Home B2 I've Grown Accustomed To Her Face B3 Just Friends B4 The Things We Did Last Summer B5 Home Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year The Dean Martin RS-6233, RS Dean Reprise Records, RS-6233, RS Television Show (LP, US 1966 6233 Martin Reprise Records 6233 Album) Dean The Dean Martin RS 6233 Reprise Records RS 6233 Canada 1966 Martin Television Show (LP) The Dean Martin R-6233, R Dean Reprise Records, R-6233, R Television Show (LP, Canada 1966 6233 Martin Reprise Records 6233 Album, Mono) Dean The Dean Martin RS-6233 Reprise Records RS-6233 US 1966 Martin Television Show (LP) The Dean Martin TV Reprise Records, R-6233, R Dean R-6233, R Show (LP, Album, Reprise Records, US 1966 6233, 6233 Martin 6233, 6233 Mono, San) Reprise Records Related Music albums to At Ease With Dean by Dean Martin Dean Martin - Somewhere There's A Someone Dean Martin - Rides Again Dean Martin - A Million And One / Shades Dean Martin - The Best Of Dean Martin Vol. -

Thanks to John Frank of Oakland, California for Transcribing and Compiling These 1960S WAKY Surveys!

Thanks to John Frank of Oakland, California for transcribing and compiling these 1960s WAKY Surveys! WAKY TOP FORTY JANUARY 30, 1960 1. Teen Angel – Mark Dinning 2. Way Down Yonder In New Orleans – Freddy Cannon 3. Tracy’s Theme – Spencer Ross 4. Running Bear – Johnny Preston 5. Handy Man – Jimmy Jones 6. You’ve Got What It Takes – Marv Johnson 7. Lonely Blue Boy – Steve Lawrence 8. Theme From A Summer Place – Percy Faith 9. What Did I Do Wrong – Fireflies 10. Go Jimmy Go – Jimmy Clanton 11. Rockin’ Little Angel – Ray Smith 12. El Paso – Marty Robbins 13. Down By The Station – Four Preps 14. First Name Initial – Annette 15. Pretty Blue Eyes – Steve Lawrence 16. If I Had A Girl – Rod Lauren 17. Let It Be Me – Everly Brothers 18. Why – Frankie Avalon 19. Since You Broke My Heart – Everly Brothers 20. Where Or When – Dion & The Belmonts 21. Run Red Run – Coasters 22. Let Them Talk – Little Willie John 23. The Big Hurt – Miss Toni Fisher 24. Beyond The Sea – Bobby Darin 25. Baby You’ve Got What It Takes – Dinah Washington & Brook Benton 26. Forever – Little Dippers 27. Among My Souvenirs – Connie Francis 28. Shake A Hand – Lavern Baker 29. It’s Time To Cry – Paul Anka 30. Woo Hoo – Rock-A-Teens 31. Sand Storm – Johnny & The Hurricanes 32. Just Come Home – Hugo & Luigi 33. Red Wing – Clint Miller 34. Time And The River – Nat King Cole 35. Boogie Woogie Rock – [?] 36. Shimmy Shimmy Ko-Ko Bop – Little Anthony & The Imperials 37. How Will It End – Barry Darvell 38.