Trauma and Resolution in Boardwalk Empire And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nomination Press Release

Elisabeth Moss as Peggy Olson Outstanding Lead Actor In A Drama Series Nashville • ABC • ABC Studios Connie Britton as Rayna James Breaking Bad • AMC • Sony Pictures Television Scandal • ABC • ABC Studios Bryan Cranston as Walter White Kerry Washington as Olivia Pope Downton Abbey • PBS • A Carnival / Masterpiece Co-Production Hugh Bonneville as Robert, Earl of Grantham Outstanding Lead Actor In A Homeland • Showtime • Showtime Presents, Miniseries Or A Movie Teakwood Lane Productions, Cherry Pie Behind The Candelabra • HBO • Jerry Productions, Keshet, Fox 21 Weintraub Productions in association with Damian Lewis as Nicholas Brody HBO Films House Of Cards • Netflix • Michael Douglas as Liberace Donen/Fincher/Roth and Trigger Street Behind The Candelabra • HBO • Jerry Productions, Inc. in association with Media Weintraub Productions in association with Rights Capital for Netflix HBO Films Kevin Spacey as Francis Underwood Matt Damon as Scott Thorson Mad Men • AMC • Lionsgate Television The Girl • HBO • Warner Bros. Jon Hamm as Don Draper Entertainment, GmbH/Moonlighting and BBC in association with HBO Films and Wall to The Newsroom • HBO • HBO Entertainment Wall Media Jeff Daniels as Will McAvoy Toby Jones as Alfred Hitchcock Parade's End • HBO • A Mammoth Screen Production, Trademark Films, BBC Outstanding Lead Actress In A Worldwide and Lookout Point in association Drama Series with HBO Miniseries and the BBC Benedict Cumberbatch as Christopher Tietjens Bates Motel • A&E • Universal Television, Carlton Cuse Productions and Kerry Ehrin -

The American Postdramatic Television Series: the Art of Poetry and the Composition of Chaos (How to Understand the Script of the Best American Television Series)”

RLCS, Revista Latina de Comunicación Social, 72 – Pages 500 to 520 Funded Research | DOI: 10.4185/RLCS, 72-2017-1176| ISSN 1138-5820 | Year 2017 How to cite this article in bibliographies / References MA Orosa, M López-Golán , C Márquez-Domínguez, YT Ramos-Gil (2017): “The American postdramatic television series: the art of poetry and the composition of chaos (How to understand the script of the best American television series)”. Revista Latina de Comunicación Social, 72, pp. 500 to 520. http://www.revistalatinacs.org/072paper/1176/26en.html DOI: 10.4185/RLCS-2017-1176 The American postdramatic television series: the art of poetry and the composition of chaos How to understand the script of the best American television series Miguel Ángel Orosa [CV] [ ORCID] [ GS] Professor at the School of Social Communication. Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador (Sede Ibarra, Ecuador) – [email protected] Mónica López Golán [CV] [ ORCID] [ GS] Professor at the School of Social Communication. Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador (Sede Ibarra, Ecuador) – moLó[email protected] Carmelo Márquez-Domínguez [CV] [ ORCID] [ GS] Professor at the School of Social Communication. Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador Sede Ibarra, Ecuador) – camarquez @pucesi.edu.ec Yalitza Therly Ramos Gil [CV] [ ORCID] [ GS] Professor at the School of Social Communication. Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador (Sede Ibarra, Ecuador) – [email protected] Abstract Introduction: The magnitude of the (post)dramatic changes that have been taking place in American audiovisual fiction only happen every several hundred years. The goal of this research work is to highlight the features of the change occurring within the organisational (post)dramatic realm of American serial television. -

MOULDINGS | STAIR PARTS | BOARDS | EXTERIOR MILLWORK MIDWEST CHICAGO DISTRIBUTION CENTER Our Our STORY FAMILY DEEP ROOTS

MOULDINGS | STAIR PARTS | BOARDS | EXTERIOR MILLWORK MIDWEST CHICAGO DISTRIBUTION CENTER our our STORY FAMILY DEEP ROOTS. HIGH STANDARDS. BRIGHT FUTURE. EMPIRE IS NOW A PART OF THE NOVO FAMILY. Founded in 1946 Empire has grown into With a geographic footprint that touches Novo Building Products is the industry door shops, retail home centers, and one of the largest millwork distribution the majority of the eastern half of the leading manufacturer and distributor of millwork manufacturing partners and manufacturing companies in the United States, Empire is positioned for mouldings, stair parts, doors, and specialty throughout the United States and parts United States. continued expansion. building products. We are proud to serve of Canada and Mexico. LJ Smith building material dealers (lumberyards), Puyallup, WA L.J. Smith Learn more at . Salem, NH novobp.com Empire Zeeland, MI L.J. Smith Empire A llentown, PA Empire Bowerston, OH Channahon, IL L.J. Smith West Valley City, UT Empire REFRESH. Ornamental Mouldings Empire Archdale, NC Dallas, TX L.J. Smith Ball Ground, GA L.J. Smith Corona, CA Southwest Dallas, TX REVIVE. L.J. Smith Empire Houston, TX Lakeland, FL RENEW. 2 empireco.com | 800.253.9000 empireco.com | 800.253.9000 3 Style is individual, personal, and unique. Make your room a reflection of you... DISCOVER YOUR STYLE HERE Achieve a similar look using: P 450 Chair Rail | 041 Crown | 5030 Architrave | 312 Casing | L 163E Base Colonial, Ranch, Traditional, Midwestern, Early American, Inviting and Timeless... The new and improved Empireco.com. Explore our comprehensive collections of mouldings, Classic Classic Mouldings enhance any home style from Midwestern to stair parts, boards, and exterior millwork as well Early American, and blend perfectly with the classic style furnishing as find inspiration for every room in the home. -

Boardwalk Empire

BOARDWALK EMPIRE "Pilot" Written by Terence Winter FIRST DRAFT April 16, 2008 EXT. ATLANTIC OCEAN - NIGHT With a buoy softly clanging in the distance, a 90-foot fishing schooner, the Tomoka, rocks lazily on the open ocean, waves gently lapping at its hull. ON DECK BILL MCCOY, pensive, 40, checks his pocket watch, then spits tobacco juice as he peers into the darkness. In the distance, WE SEE flickering lights, then HEAR the rumble of motorboats approaching, twenty in all. Their engines idle as the first pulls up and moors alongside. BILL MCCOY (calling down) Sittin' goddarnn duck out here. DANNY MURDOCH, tough, 30s, looks up from the motorboat, where he's accompanied by a YOUNG HOOD, 18. MURDOCH So move it then, c'mon. ON DECK McCoy yankS a canvas tarp off a mountainous stack of netted cargo -- hundreds of crates marked 'Canadian Club Whiskey·. With workmanlike precision, he and .. three CREWMAN hoist the first load of two dozen crates up and over the side, lowering it down on a pulley. As the net reaches the motorboat: MURDOCH (CONT'D) (to the Young Hood) Liquid gold, boyo. They finish setting the load in place, then Murdoch guns the motorboat and heads off. Another boat putters in to take his slot as the next cargo net is lowered. TRACK WITH MURDOCH'S MOTORBOAT as it heads inland through the darkness over the water. Slowly, a KINGDOM OF LIGHTS appears on the horizon, with grand hotels, massive neon signs, carnival rides and giant lighted piers lining its shore. As we draw closer, WE HEAR faint music which grows louder and LOUDER -- circus calliope mixed with raucous Dixieland jazz. -

Boardwalk Empire

BOARDWAI,K EIITPIRE ,'Pi1ot " written by Terence Wint,er FIRST DRAFT April L6, 2008 G *ffi EXT. ATLAI:i"IIC OCEAN - NIGHT With a buoy softly clangring in the dist,ance, a 90-fooE fishing schooner, the ?omoka, rocks lazily on the open ocean, waves gentLy lapping at its hulI. ON DECK BILL MCCOY, pensive , 40, checks his pocket wauch, then spius tobaeco juice as he peers into the darkness. In the distance, VgE SEE flickering lights, then HEAR the rumble of motorboats approaching, twenty in atl. Their engines idle as the first pulls up and moors alongside. BTLL MCCOY (calling dovrn) Sittin' goddamn duck out here. DANIIy MURDOCH, tough, 30s, looks up from the motorboatr, where he's accompanied. by a YOIING HOOD, 18. MIJRDOCH So move it. then, c,mon. ON DECK McCoy yanks a canvas tarp off a mountainous stack of netted earqo -- hundreds of crates marked "Canadian Club Whiskey'. WiEh worlsnanlike precision, he and three CRSWI,IAN hoist the first load of two dozen crates up and over the side, lowering it down on a pulley. As the net reaches the motorboaL: MURDOCH (CONT'D) (to the Young Hood) Liquid go1d, boyo. They finish setting the load in place, then Murdoch guns the motorboat and heads off. Another boat putters in to take his s1ot, as the next cargo neb is lowered. TBACK WITH MURDOCH'S MOTORBOAT as it heads inland through the darkness over the water. Slowly, a KINGDOM OF LIGHTS appears on the horizon, with grand hotels, massive neon signs, carnival rides and giant lighted piers li-ning its shore. -

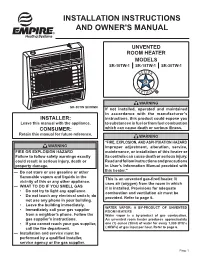

Installation INSTRUCTIONS and OWNER's MANUAL

Installation INSTRUCTIONS AND OWNER'S MANUAL UNVENTED ROOM HEATER MODELS SR-10TW-1 SR-18TW-1 SR-30TW-1 WARNING SR-30TW SHOWN If not installed, operated and maintained in accordance with the manufacturer’s INSTALLER: instructions, this product could expose you Leave this manual with the appliance. to substances in fuel or from fuel combustion CONSUMER: which can cause death or serious illness. Retain this manual for future reference. WARNING “FIRE, EXPLOSION, AND ASPHYXIATION HAZARD WARNING Improper adjustment, alteration, service, FIRE OR EXPLOSION HAZARD maintenance, or installation of this heater or Failure to follow safety warnings exactly its controls can cause death or serious injury. could result in serious injury, death or Read and follow instructions and precautions property damage. in User’s Information Manual provided with — Do not store or use gasoline or other this heater.” flammable vapors and liquids in the This is an unvented gas-fired heater. It vicinity of this or any other appliance. uses air (oxygen) from the room in which — WHAT TO DO IF YOU SMELL GAS it is installed. Provisions for adequate • Do not try to light any appliance. combustion and ventilation air must be • Do not touch any electrical switch; do provided. Refer to page 6. not use any phone in your building. • Leave the building immediately. WATER VAPOR: A BY-PRODUCT OF UNVENTED • Immediately call your gas supplier ROOM HEATERS from a neighbor’s phone. Follow the Water vapor is a by-product of gas combustion. gas supplier’s instructions. An unvented room heater produces approximately • If you cannot reach your gas supplier, one (1) ounce (30ml) of water for every 1,000 BTU’s call the fire department. -

From Disney to Disaster: the Disney Corporation’S Involvement in the Creation of Celebrity Trainwrecks

From Disney to Disaster: The Disney Corporation’s Involvement in the Creation of Celebrity Trainwrecks BY Kelsey N. Reese Spring 2021 WMNST 492W: Senior Capstone Seminar Dr. Jill Wood Reese 2 INTRODUCTION The popularized phrase “celebrity trainwreck” has taken off in the last ten years, and the phrase actively evokes specified images (Doyle, 2017). These images usually depict young women hounded by paparazzi cameras that are most likely drunk or high and half naked after a wild night of partying (Doyle, 2017). These girls then become the emblem of celebrity, bad girl femininity (Doyle, 2017; Kiefer, 2016). The trainwreck is always a woman and is usually subject to extra attention in the limelight (Doyle, 2017). Trainwrecks are in demand; almost everything they do becomes front page news, especially if their actions are seen as scandalous, defamatory, or insane. The exponential growth of the internet in the early 2000s created new avenues of interest in celebrity life, including that of social media, gossip blogs, online tabloids, and collections of paparazzi snapshots (Hamad & Taylor, 2015; Mercer, 2013). What resulted was 24/7 media access into the trainwreck’s life and their long line of outrageous, commiserable actions (Doyle, 2017). Kristy Fairclough coined the term trainwreck in 2008 as a way to describe young, wild female celebrities who exemplify the ‘good girl gone bad’ image (Fairclough, 2008; Goodin-Smith, 2014). While the coining of the term is rather recent, the trainwreck image itself is not; in their book titled Trainwreck, Jude Ellison Doyle postulates that the trainwreck classification dates back to feminism’s first wave with Mary Wollstonecraft (Anand, 2018; Doyle, 2017). -

Rap and Feng Shui: on Ass Politics, Cultural Studies, and the Timbaland Sound

Chapter 25 Rap and Feng Shui: On Ass Politics, Cultural Studies, and the Timbaland Sound Jason King ? (body and soul ± a beginning . Buttocks date from remotest antiquity. They appeared when men conceived the idea of standing up on their hind legs and remaining there ± a crucial moment in our evolution since the buttock muscles then underwent considerable development . At the same time their hands were freed and the engagement of the skull on the spinal column was modified, which allowed the brain to develop. Let us remember this interesting idea: man's buttocks were possibly, in some way, responsible for the early emergence of his brain. Jean-Luc Hennig the starting point for this essayis the black ass. (buttocks, behind, rump, arse, derriere ± what you will) like mymother would tell me ± get your black ass in here! The vulgar ass, the sanctified ass. The black ass ± whipped, chained, beaten, punished, set free. territorialized, stolen, sexualized, exercised. the ass ± a marker of racial identity, a stereotype, property, possession. pleasure/terror. liberation/ entrapment.1 the ass ± entrance, exit. revolving door. hottentot venus. abner louima. jiggly, scrawny. protrusion/orifice.2 penetrable/impenetrable. masculine/feminine. waste, shit, excess. the sublime, beautiful. round, circular, (w)hole. The ass (w)hole) ± wholeness, hol(e)y-ness. the seat of the soul. the funky black ass.3 the black ass (is a) (as a) drum. The ass is a highlycontested and deeplyambivalent site/sight . It maybe a nexus, even, for the unfolding of contemporaryculture and politics. It becomes useful to think about the ass in terms of metaphor ± the ass, and the asshole, as the ``dirty'' (open) secret, the entrance and the exit, the back door of cultural and sexual politics. -

BOARDWALK EMPIRE "In God We Trust" by Reginald Beltran Based

BOARDWALK EMPIRE "In God We Trust" By Reginald Beltran Based on characters by Terence Winter Reginald Beltran [email protected] FADE IN: EXT. FOREST - DAY A DEAD DOE lies on the floor. Blood oozes out of a fatal bullet wound on its side. Its open, unblinking eyes stare ahead. The rustling sound of leaves. The fresh blood attracts the attention of a hungry BEAR. It approaches the lifeless doe, and claims the kill for itself. The bear licks the fresh blood on the ground. More rustling of the undergrowth. The bear looks up and sees RICHARD HARROW, armed with a rifle, pushing past a thicket of trees and branches. For a moment, the two experienced killers stare at each other with unblinking eyes. One set belongs to a primal predator and the other set is half man, half mask. The bear stands on its two feet. It ROARS at its competitor. Richard readies his rifle for a shot, but the rifle is jammed. The bear charges. Calmly, Richard drops to one knee, examines the rifle and fixes the jam. He doesn’t miss a beat. He steadies the rifle and aims it. BANG! It’s a sniper’s mark. The bear drops to the ground immediately with a sickening THUD. Blood oozes out of a gunshot wound just under its eyes - the Richard Harrow special. EXT. FOREST - NIGHT Even with a full moon, light is sparse in these woods. Only a campfire provide sufficient light and warmth for Richard. A spit has been prepared over the fire. A skinned and gutted doe lies beside the campfire. -

Lee Daniels on Empire: the Show Has Already Changed Homophobes' Minds

8/15/2018 Empire on Fox: Lee Daniels on his Show's Effect on Homophobia | Time Lee Daniels on Empire: The Show Has Already Changed Homophobes' Minds Lee Daniels on Dec. 1, 2014 in New York City. Theo Warg—Getty Images / IFP By LILY ROTHMAN January 7, 2015 Lee Daniels is best known as the lmmaker behind gritty independent lms like Precious, but his new project is the slick primetime drama Empire, premiering Jan. 7 on Fox, which he co-created with Danny Strong. Daniels recently spoke to TIME about the show, and how — despite not being independently made — http://time.com/3656583/lee-daniels-empire/ 1/3 8/15/2018 Empire on Fox: Lee Daniels on his Show's Effect on Homophobia | Time it’s a personal story. The Shakespeare-inected tale of record mogul Lucious Lyon (Terrence Howard), his ex-wife Cookie (Taraji P. Henson) and their sons Andre, Jamal and Hakeem, often draws on stories from his own life. And, he tells TIME, the show is already making a difference toward his larger aim of increasing tolerance among its audience: TIME: You’ve told a story about trying on your mother’s shoes as a child. There’s a scene in the Empire pilot that sounds very similar to that episode, where Lucious reacts to seeing his young son do just that… Lee Daniels: I was terried of that scene. My sister was an extra — she’s in the scene — and when the kid put the shoes on, having him walk in front of his father, I had a meltdown. -

Shakespeare Unlimited: How King Lear Inspired Empire

Shakespeare Unlimited: How King Lear Inspired Empire Ilene Chaiken, Executive Producer Interviewed by Barbara Bogaev A Folger Shakespeare Library Podcast March 22, 2017 ---------------------------- MICHAEL WITMORE: Shakespeare can turn up almost anywhere. [A series of clips from Empire.] —How long you been plannin’ to kick my dad off the phone? —Since the day he banished me. I could die a thousand times… just please… From here on out, this is about to be the biggest, baddest company in hip-hop culture. Ladies and gentlemen, make some noise for the new era of Hakeem Lyon, y’all… MICHAEL: From the Folger Shakespeare Library, this is Shakespeare Unlimited. I‟m Michael Witmore, the Folger‟s director. This podcast is called “The World in Empire.” That clip you heard a second ago was from the Fox TV series Empire. The story of an aging ruler— in this case, the head of a hip-hop music dynasty—who sets his three children against each other. Sound familiar? As you will hear, from its very beginning, Empire has fashioned itself on the plot of King Lear. And that‟s not the only Shakespeare connection to the program. To explain all this, we brought in Empire’s showrunner, the woman who makes everything happen on time and on budget, Ilene Chaiken. She was interviewed by Barbara Bogaev. ---------------------------- BARBARA BOGAEV: Well, Empire seems as if its elevator pitch was a hip-hop King Lear. Was that the idea from the start? ILENE CHAIKEN: Yes, as I understand it, now I didn‟t create Empire— BOGAEV: Right, because you‟re the showrunner, and first there‟s a pilot, and then the series gets picked up, and then they pick the showrunner. -

Accepted Manuscript Version

Research Archive Citation for published version: Kim Akass, and Janet McCabe, ‘HBO and the Aristocracy of Contemporary TV Culture: affiliations and legitimatising television culture, post-2007’, Mise au Point, Vol. 10, 2018. DOI: Link to published article in journal's website Document Version: This is the Accepted Manuscript version. The version in the University of Hertfordshire Research Archive may differ from the final published version. Copyright and Reuse: This manuscript version is made available under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives License CC BY NC-ND 4.0 ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ ), which permits non-commercial re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited, and is not altered, transformed, or built upon in any way. Enquiries If you believe this document infringes copyright, please contact Research & Scholarly Communications at [email protected] 1 HBO and the Aristocracy of TV Culture : affiliations and legitimatising television culture, post-2007 Kim Akass and Janet McCabe In its institutional pledge, as Jeff Bewkes, former-CEO of HBO put it, to ‘produce bold, really distinctive television’ (quoted in LaBarre 90), the premiere US, pay- TV cable company HBO has done more than most to define what ‘original programming’ might mean and look like in the contemporary TV age of international television flow, global media trends and filiations. In this article we will explore how HBO came to legitimatise a contemporary television culture through producing distinct divisions ad infinitum, framed as being rooted outside mainstream commercial television production. In creating incessant divisions in genre, authorship and aesthetics, HBO incorporates artistic norms and principles of evaluation and puts them into circulation as a succession of oppositions— oppositions that we will explore throughout this paper.