Costs and Effects of Extending Health Insurance Coverage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appendix File Anes 1988‐1992 Merged Senate File

Version 03 Codebook ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ CODEBOOK APPENDIX FILE ANES 1988‐1992 MERGED SENATE FILE USER NOTE: Much of his file has been converted to electronic format via OCR scanning. As a result, the user is advised that some errors in character recognition may have resulted within the text. MASTER CODES: The following master codes follow in this order: PARTY‐CANDIDATE MASTER CODE CAMPAIGN ISSUES MASTER CODES CONGRESSIONAL LEADERSHIP CODE ELECTIVE OFFICE CODE RELIGIOUS PREFERENCE MASTER CODE SENATOR NAMES CODES CAMPAIGN MANAGERS AND POLLSTERS CAMPAIGN CONTENT CODES HOUSE CANDIDATES CANDIDATE CODES >> VII. MASTER CODES ‐ Survey Variables >> VII.A. Party/Candidate ('Likes/Dislikes') ? PARTY‐CANDIDATE MASTER CODE PARTY ONLY ‐‐ PEOPLE WITHIN PARTY 0001 Johnson 0002 Kennedy, John; JFK 0003 Kennedy, Robert; RFK 0004 Kennedy, Edward; "Ted" 0005 Kennedy, NA which 0006 Truman 0007 Roosevelt; "FDR" 0008 McGovern 0009 Carter 0010 Mondale 0011 McCarthy, Eugene 0012 Humphrey 0013 Muskie 0014 Dukakis, Michael 0015 Wallace 0016 Jackson, Jesse 0017 Clinton, Bill 0031 Eisenhower; Ike 0032 Nixon 0034 Rockefeller 0035 Reagan 0036 Ford 0037 Bush 0038 Connally 0039 Kissinger 0040 McCarthy, Joseph 0041 Buchanan, Pat 0051 Other national party figures (Senators, Congressman, etc.) 0052 Local party figures (city, state, etc.) 0053 Good/Young/Experienced leaders; like whole ticket 0054 Bad/Old/Inexperienced leaders; dislike whole ticket 0055 Reference to vice‐presidential candidate ? Make 0097 Other people within party reasons Card PARTY ONLY ‐‐ PARTY CHARACTERISTICS 0101 Traditional Democratic voter: always been a Democrat; just a Democrat; never been a Republican; just couldn't vote Republican 0102 Traditional Republican voter: always been a Republican; just a Republican; never been a Democrat; just couldn't vote Democratic 0111 Positive, personal, affective terms applied to party‐‐good/nice people; patriotic; etc. -

![Presidential Files; Folder: 7/28/77 [2]; Container 34](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1583/presidential-files-folder-7-28-77-2-container-34-341583.webp)

Presidential Files; Folder: 7/28/77 [2]; Container 34

7/28/77 [2] Folder Citation: Collection: Office of Staff Secretary; Series: Presidential Files; Folder: 7/28/77 [2]; Container 34 To See Complete Finding Aid: http://www.jimmycarterlibrary.gov/library/findingaids/Staff_Secretary.pdf WITHDRAWAL SHEET (PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARIES) FORM OF CORRESPONDENTS OR TITLE DATE RESTRICTION DOCUMENT letter From President Carter to Sen. Inouye (5 pp.) 7/27/77 A w/att. Intelligence Oversight Board/ enclosed in Hutcheson to Frank Moore 7/28~~? r.l I I {)~ L 7 93 FILE LOCATION Carter Presidential Papers- Staff Of fcies, Off~£e of the Staff Sec.- Pres. Handwriting File 7/28777 [2] Box 41' RESTRICTION CODES (A) Closed by Executive Order 12356'governing access to national security information. B) Closed by statute or by the agency which originated the document. C) Closed in accordance with restrictions contained in the donor's deed of gift. t-· 1\TIONAL ARCHIVES AND RECORDS ADMINISTRATION. NA FORM 1429 (6-85) t ~ l-~~- ------------------------------~I . ( ~, 1. • I ' \ \ . • THE WHITE HOUSE WASHINGTON July 28, 1977 ·I ! Frank Moore ( . I The attached was returned in the President's outbox. I . It is forwarded to you for appropriate handling. Rick Hutcheson cc: The Vice President Hamilton Jordan Bob Lipshutz Zbig Brzezinski • I Joe Dennin ! RE: LETTER TO SENATOR INOUYE ON INTELLIGENCE OVERSIGHT \ BOARD t ' . ·\ •I ' 1 THE WHITE HOUSE WASHINGTON FOR STAFFING FOR INFORMATION FROH PRESIDENT'S OUTBOX LOG IN TO PRESIDENT TODAY z IMMEDIATE TURNAROUND 0 I H ~ ~·'-'\ 8 H c.... C. (Ji u >t ,::X: ~ / MONDALE ENROLLED BILL COSTANZA AGENCY REPORT EIZENSTAT CAB DECISION I JORDAN EXECUTIVE ORDER I LIPSHUTZ Comments due to / MOORE of'"• ~ ,_. -

NOTE ,Present Program in Light of the Federal Statutory

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 247 458 CE 039 556 TITLE Vocational Rehabilitation. Hearing before the Subcommittee on Select Educ ion of the-,Committee on Education and Labor, House Representatives, Ninety-Eighth Congress, First Session (Harrisburg, Pennsylvania). INSTITUTION Congress of the U.S., Washington, D.C. House Committee on Education and Labor. PUB DATE 25 Jul 83 NOTE 80p. PUB TYPE Legal/Legislative/Regulatory Materials (090) Viewpoints (12q) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC04 Plus Postage. DESNRIPTOR Adults; *Compliance (Legal); *Disabilities; *Federal 4, Legislation; Federal Regulation; Federal State Relationship; Hearings; *State Piograms; Vocational Education; *Vocational Rehabilitation IDENTIFIERS Congress 98th; *Pennsylvania; *Rehabilitation Act 1973 t ABSTRACT This is a congressional oversight hearing on the vocational rehabilitation program in Pennsylvania. It looks at the ,present program in light of the Federal statutory requirements and legislative intent. Testimony includes statements,,prepared statements, letters, supplemental. materials, etc., from a state senator, a Representative in Congress, and individuals representing the Pennsylvania Social Services Union, Pittsburgh; Office of Vocational Rehabilitation, Harrisburg; Harmarville Rehabilitation Center, Inc., Pittsburgh; pennsylvdhia Office of Vocational Rehabilitation;Pennsylvania Board. of Vocational Rehabilitation; 'Independent Living Center, Harmarville; Open Doors for the Handicapped of Allegheny County; Pennsylvania Coalition of Citizens with Disabilities; Rehabilitation Services -

DOCUM ED 303 584 ENT RESUME CE 051 660 TITLE Hearing On

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 303 584 CE 051 660 TITLE Hearing on National Youth Corps, H.R. 18 and H.R. 460. Hearing before the Subcommittee on Employment Opportunities of the Committee on Education and Labor. House of Representatives, One Hundredth Congress, Second Session. INSTITUTION Congress of the U.S., Washington, D.C. House Committee on Education and Labor. PUB DATE 15 Jun 88 NOTE 48p.; Serial No. 100-81. For related documents, see CE 051 658-661. AVAILABLE FROMSuperintendent of Documents, Congressional Sales Office, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC 20402. PUB TYPE Legal/Legislative/Regulatory Materials (090) -- Viewpoints (120) EDRS PRICE MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Adolescents; Adult Basic Education; Citizen Participation; Community Development; *Disadvantaged Youth; Educational Needs; *Employment Programs; *Federal Legislation; *Federal Programs; Hearings; Job Training; Postsecondary Education; Program Implementation; Public Policy; *Public Service; Ycung Adults IDENTIFIERS Congress 100th; Pennsylvania; *Youth Service ABSTRACT This document contains transcripts of oral and written testimony from witnesses at a hearing on H.R. 18 and H.R. 460, which would create a National Youth Corps. The National Youth Corps proposal links two other proposals, the Conservation Corps biAl and the National Youth Service bill, into a comprehensive bill to provide alternatives for youth in both urban and rural areas. The National Youth Corps bill proposes to hire young people to perform public service, such as conservation and clean-up -

Salsa2bills 1..5

By:AAGoolsby H.R.ANo.A14 RESOLUTION 1 WHEREAS, The city of Dallas, which has contributed so much to 2 the development of Texas and done so much to define Texas in the 3 eyes of the world, is celebrating its 150th anniversary in 2006; and 4 WHEREAS, Founded by John Neely Bryan near a ford on the 5 Trinity River, Dallas was platted in 1844 and incorporated on 6 February 2, 1856; it has served as the county seat of Dallas County 7 ever since the latter jurisdiction was organized in 1846; and 8 WHEREAS, Dallas quickly became a service center for the 9 surrounding area and had a recorded population of 678 on the eve of 10 the Civil War; in addition to North American Anglos and African 11 Americans, residents included Belgians, Swiss, Germans, and 12 French; following the war, many freed slaves migrated to Dallas in 13 search of work and settled in freedmen 's towns on the outskirts of 14 the city; and 15 WHEREAS, The arrival of the Houston and Texas Central Railway 16 in 1872 and the Texas and Pacific Railway in 1873 secured the city 's 17 future; from 3,000 citizens in 1870, the population rose to more 18 than 10,000 in 1880 and soared to over 38,000 in 1890, when Dallas 19 ranked as the largest city in Texas; advantageously situated, 20 Dallas shipped such raw materials to northern and eastern markets 21 as cotton, leather, and--until the southern herd was 22 extinguished--buffalo hides; and 23 WHEREAS, By 1900, Dallas boasted the largest inland cotton 24 market in the world and also ranked as the world 's chief 79S30262 MMS-D 1 H.R.ANo.A14 -

Status of Most Corrupt Alumni……………………………………………………45

TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary……………………………………………………………………………….1 Chapter I: A Foundation for Failure………………………………………………………………3 Chapter II: Ethics Transformed, but Under Attack………………………………………………15 Chapter III: Solutions…………………………………………………………………………….23 Appendices……………………………………………………………………………………….25 Appendix A: Most Corrupt Alumni and Ignored Allegations of Misconduct…………………...26 Appendix B: History of the Ethics Committees…………………………………………………30 Appendix C: Appropriated Budgets of the House and Senate Ethics Committees and OCE…....37 Appendix D: OCE Actions……………………………………………………………………....38 Appendix E: Alumni List Numbers……………………………………………………………...39 Appendix F: Status of Most Corrupt Alumni……………………………………………………45 Appendix G: Alleged Violations by Alumni of CREW’s “Most Corrupt” Reports…………….46 Appendix H: Alumni of CREW’s Most Corrupt (Current Members of Congress)……………...47 THE MOST CORRUPT MEMBERS OF CONGRESS “UNFINISHED BUSINESS” Earmarking for personal gain. Skirting campaign finance laws. Adultery and sexual harassment. CREW has spent the past five years shining a spotlight on the extensive violations of the public trust committed by members of Congress. After publishing five “Most Corrupt Members of Congress” reports, it’s clear that the system for holding accountable those members of Congress who sacrifice the public interest for special interests is not working. Whether members take bribes, violate gift rules, or flout campaign finance regulations, those charged with enforcement look the other way. Over the past five years, CREW has uncovered more than 425 instances of potential violations of ethics rules by no fewer than 56 members of Congress. Of those, 37 members have never been investigated by any of the congressional ethics bodies, and 26 “Most Corrupt” members continue to serve in Congress. Because of that, this year, CREW is naming the House Committee on Standards of Official Conduct and the Senate Select Committee on Ethics to its “Most Corrupt” list, for standing by and allowing members of Congress to break the rules with impunity. -

Presidential Scholars Program: 2019 Distinguished Teachers

2019 U.S. Presidential Scholars Program’s Distinguished Teachers Mr. William Adler, Hathaway Brown School, OH, Math Nominating Scholar: Yasmine Zein Ms. Jo Ahlm, Raton High School, NM, Science Nominating Scholar: Donavin Myles Mendez Mr. Stephen Arel, Davies High School, ND, Social Studies (Economics and Government) Nominating Scholars: Dyuti Dawn and Jutning Shen Mr. Ross Arseneau, Detroit Country Day School, MI, Math Nominating Scholar: Madeleine Yang Mr. Drew Bagwell, Auburn High School, AL, Biology Nominating Scholar: Donghan Park Ms. Suzanne Bailey, Virgil I. Grissom High School, AL, Social Studies Nominating Scholar: Alison Hu Mr. Hector Barrera, Mater Lakes Academy High School, FL, Music Nominating Scholar: Mercedes F. Ferreira-Dias Dr. Joshua Bartee, Bishop Gorman High School, NV, English Nominating Scholar: Arthur Acuna Mr. Steve Bartlett, Centennial High School, ID, Math Nominating Scholar: John Chen Ms. Minu Basu, Dougherty Valley High School, CA, AP Biology Nominating Scholar: Won Bin Lee Bruce Beck, Malverne Senior High School, NY, Science and Engineering Nominating Scholar: Nelson Chow Kris Bence, Riverside High School, SC, Band Nominating Scholar: Jiaying Tong Dr. Philip Benge, Mississippi School for Mathematics & Science, MS, Math Nominating Scholar: Hamilton Wan Mr. James Berger, John Adams High School, IN, History / Social Sciences Nominating Scholar: Stanley Rozenblit Jill Bickel, duPont Manual Magnet High School, KY, English Nominating Scholar: Allison Kim Tien Tu Ms. Alexandra Blumer, National Cathedral School, DC, English Nominating Scholar: Shiva Khanna Yamamoto Mr. James Bobbitt, Pensacola High School, FL, Math Nominating Scholar: Ahna Bella Cecil Ms. Anne Bonnycastle, Crofton House School, BC, Music Nominating Scholar: Elizabeth Baranes Ms. Gay Brasher, Leland High School, CA, Speech and Debate Nominating Scholar: Cynthia Zhou Ms. -

H. Doc. 108-222

NINETY-EIGHTH CONGRESS JANUARY 3, 1983, TO JANUARY 3, 1985 FIRST SESSION—January 3, 1983, to November 18, 1983 SECOND SESSION—January 23, 1984, 1 to October 12, 1984 VICE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES—GEORGE H. W. BUSH, of Texas PRESIDENT PRO TEMPORE OF THE SENATE—J. STROM THURMOND, of South Carolina SECRETARY OF THE SENATE—WILLIAM F. HILDENBRAND, of the District of Columbia SERGEANT AT ARMS OF THE SENATE—HOWARD S. LIEBENGOOD, of Virginia; LARRY E. SMITH, 2 of Virginia SPEAKER OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES—THOMAS P. O’NEILL, JR., 3 of Massachusetts CLERK OF THE HOUSE—BENJAMIN J. GUTHRIE, 3 of Virginia SERGEANT AT ARMS OF THE HOUSE—JACK RUSS, 3 of Maryland DOORKEEPER OF THE HOUSE—JAMES T. MOLLOY, 3 of New York POSTMASTER OF THE HOUSE—ROBERT V. ROTA, 3 of Pennsylvania ALABAMA Eldon D. Rudd, Scottsdale Tom Lantos, San Mateo SENATORS James F. McNulty, Jr., Bisbee Edwin V. W. Zschau, Los Altos Norman Y. Mineta, San Jose Howell T. Heflin, Tuscumbia ARKANSAS Norman D. Shumway, Stockton Jeremiah Denton, Mobile SENATORS Tony Coelho, Merced REPRESENTATIVES Dale Bumpers, Charleston Leon E. Panetta, Carmel Valley Jack Edwards, Mobile David H. Pryor, Camden Charles Pashayan, Jr., Fresno William L. Dickinson, Montgomery Richard H. Lehman, Sanger Bill Nichols, Sylacauga REPRESENTATIVES Robert J. Lagomarsino, Ventura Tom Bevill, Jasper Bill Alexander, Osceola William M. Thomas, Bakersfield Ronnie G. Flippo, Florence Ed Bethune, Searcy Bobbi Fiedler, Northridge Ben Erdreich, Birmingham John P. Hammerschmidt, Harrison Carlos J. Moorhead, Glendale Richard C. Shelby, Tuscaloosa Beryl F. Anthony, Jr., El Dorado Anthony C. Beilenson, Los Angeles Henry A. -

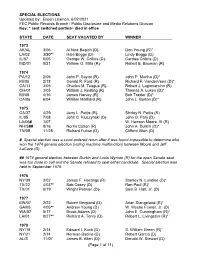

Special Election Dates

SPECIAL ELECTIONS Updated by: Eileen Leamon, 6/02/2021 FEC Public Records Branch / Public Disclosure and Media Relations Division Key: * seat switched parties/- died in office STATE DATE SEAT VACATED BY WINNER 1973 AK/AL 3/06 Al Nick Begich (D)- Don Young (R)* LA/02 3/20** Hale Boggs (D)- Lindy Boggs (D) IL/07 6/05 George W. Collins (D)- Cardiss Collins (D) MD/01 8/21 William O. Mills (R)- Robert E. Bauman (R) 1974 PA/12 2/05 John P. Saylor (R)- John P. Murtha (D)* MI/05 2/18 Gerald R. Ford (R) Richard F. VanderVeen (D)* CA/13 3/05 Charles M. Teague (R)- Robert J. Lagomarsino (R) OH/01 3/05 William J. Keating (R) Thomas A. Luken (D)* MI/08 4/16 James Harvey (R) Bob Traxler (D)* CA/06 6/04 William Mailliard (R) John L. Burton (D)* 1975 CA/37 4/29 Jerry L. Pettis (R)- Shirley N. Pettis (R) IL/05 7/08 John C. Kluczynski (D)- John G. Fary (D) LA/06# 1/07 W. Henson Moore, III (R) NH/S## 9/16 Norris Cotton (R) John A. Durkin (D)* TN/05 11/25 Richard Fulton (D) Clifford Allen (D) # Special election was a court-ordered rerun after it was found impossible to determine who won the 1974 general election (voting machine malfunction) between Moore and Jeff LaCaze (D). ## 1974 general election between Durkin and Louis Wyman (R) for the open Senate seat was too close to call and the Senate refused to seat either candidate. Special election was held in September 1975. -

One Hundred Second Congress January 3, 1991 to January 3, 1993

ONE HUNDRED SECOND CONGRESS JANUARY 3, 1991 TO JANUARY 3, 1993 FIRST SESSION—January 3, 1991, to January 3, 1992 SECOND SESSION—January 3, 1992, to October 9, 1992 VICE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES—J. DANFORTH QUAYLE, of Indiana PRESIDENT PRO TEMPORE OF THE SENATE—ROBERT C. BYRD, of West Virginia SECRETARY OF THE SENATE—WALTER J. STEWART, of Washington, D.C. SERGEANT AT ARMS OF THE SENATE—MARTHA S. POPE, 1 of Connecticut SPEAKER OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES—THOMAS S. FOLEY, 2 of Washington CLERK OF THE HOUSE—DONNALD K. ANDERSON, 2 of California SERGEANT AT ARMS OF THE HOUSE—JACK RUSS, 3 of Maryland; WERNER W. BRANDT, 4 of New York DOORKEEPER OF THE HOUSE—JAMES T. MALLOY, 2 of New York POSTMASTER OF THE HOUSE—ROBERT V. ROTA, 2 of Pennsylvania DIRECTOR OF NON-LEGISLATIVE AND FINANCIAL SERVICES 5—LEONARD P. WISHART III, 6 of New Jersey ALABAMA John S. McCain III, Phoenix Pete Wilson, 9 San Diego 10 SENATORS REPRESENTATIVES John Seymour, Anaheim Dianne Feinstein, 11 San Francisco Howell T. Heflin, Tescumbia John J. Rhodes III, Mesa Richard C. Shelby, Tuscaloosa Morris K. Udall, 7 Tucson REPRESENTATIVES REPRESENTATIVES Ed Pastor, 8 Phoenix Frank Riggs, Santa Rosa Wally Herger, Rio Oso Sonny Callahan, Mobile Bob Stump, Tolleson William L. Dickinson, Montgomery Jon Kyl, Phoenix Robert T. Matsui, Sacramento Glen Browder, Jacksonville Jim Kolbe, Tucson Vic Fazio, West Sacramento Tom Bevill, Jasper Nancy Pelosi, San Francisco Bud Cramer, Huntsville ARKANSAS Barbara Boxer, Greenbrae George Miller, Martinez Ben Erdreich, Birmingham SENATORS Claude Harris, Tuscaloosa Ronald V. Dellums, Oakland Dale Bumpers, Charleston Fortney Pete Stark, Oakland ALASKA David H. -

1234 Massachusetts Avenue, NW • Suite 103 • Washington, DC 20005 • 202-347-1234

1234 Massachusetts Avenue, NW • Suite 103 • Washington, DC 20005 • 202-347-1234 #100-33 Information Alert: October 11, 1988 Medicaid Reform House Hearing TO: DD Council Executive Directors FROM: Susan Ames-Zierman On September 30, 1988, Congressman Henry Waxroan held a hearing on his bill, H.R.5233, and that of Congressman Florio, H.R. 3454, which is the House companion bill to Senator Chafee's S. 1673, the Medicaid Home and Community Quality Services Act. Mr. Waxman's opening statement is enclosed. Attached is testimony given by Congressman Steve Bartlett of Texas, Senator Chafee, and the Congressional Budget Office. Also enclosed is a side-by-side comparison of the two bills and current Medicaid law developed by the Congressional Research Service of the Library of Congress.. Senator Bentsen has agreed to mark up Senator Chafee's bill early in the 101st Congress. Should Senator Bentsen become the Vice-President, Senator Matsunaga of Hawaii would become Senate Finance Committee Chairman and would, in all likelihood, be agreeable to moving forward. Congressman Waxman, while not going as far as to discuss mark-up on either his or Florio's bill, did agree, in both his opening and closing statements, to work with Congressman Florio on a compromise early in the next Congress. A list of current co-sponsors of the Chafee/Florio bills is attached. We need to keep all those returning Senators and Congressman on-board when this process begins anew in January. For those in your Congressional delegations who are not current co-sponsors, plan some visits to programs while they are home campaigning this fall and over the holidays. -

City Council Election History

City of Dallas Office of the City Secretary HISTORY OF MAYORS & CITY COUNCILS Disclaimer: The Dallas City Secretary's Office provides this database as an informational resource. Every reasonable effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of information contained in this document. Always consult original sources if accuracy is in doubt. i KEY NOTES 1 Changed married names to first names ex: Mrs. 2 Did not include deceased date unless the person died in office 3 Corrected spelling of a person's name ex: Campbell to Cabell 4 Corrected misprint of dates (year) ex: 1877 to 1871; 5 Corrrected misprint in election date ex: December 23, 1976 to correct December 23, 1975 6 Updated history from past book ex: 1996 - present (copy of canvass available for confirmation) 7 Entered data where information was missing ex: Entered minute book, page #; resolution #, date of election 8 Starting in 1872, indentified long, short terms with an * for long term ex: see footnote 9 Added form of government to page heading ex: Mayor-Alderman 10 Replaced initials and nicknames with proper name when possible ex: J. H. Bryan to John H. Bryan 11 Months will be spelled out for clarity ex: 4/4/1870 to April 4, 1870 12 Candidate votes listed highest to lowest Previous book ends with the 1993-1995 Election Term. Starting with 1995 to present, city council action items 13 used as documentation to validate the information provided 14 Extensive research conducted and no reference to first name found ex: _____ Russell 15 Updated election information to show key personnel in public office ex: City Attorney, City Engineer, Marshall ii City of Dallas Office of the City Secretary HISTORY OF MAYORS & CITY COUNCILS This database was developed to delineate the election history for the Dallas City Council (1866 to present).