The Dominguez Struggle for Status by Conor Mcgarry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mar-Apr (1093 MB

OMNILORE NEWS March 2012 1 Volume 21 Issue 2 www.omnilore.org March 2012 OLLI AT CSUDH “Libraries of the Future” at the Spring Forum OMNILORE by Carol Kerster mniloreans are fortunate! We have heard a OMNILORE NEWS is a publication of variety of experts entertain, enlighten, and/or OMNILORE, a Learning-in-Retirement educate us at our quarterly Forum meetings. Organization, a program of the Osher Life- O While most of our speakers have followed a direct long Learning Institute at the California State University Dominguez Hills course from their education and experience to their current occupations, this is not the case for the BOARD OF DIRECTORS speaker at our next Forum on April 30: Katherine R. Gould, director of the Palos Verdes Library District, Elected Officers whose eclectic background enhances her qualifica- President Bill Gargaro tions to share her ideas about how our traditionally paper-based library systems are transitioning into VP - Academics Jade Suzanne Neely Katherine Gould VP - Administration Howard Korman the digital world. Treasurer Jim Slattery Armed with a magna cum laude B.A. from Brandon University in Manitoba, Recording Secretary RosaLee Saikley Canada, and an M.S. in Library and Information Management from USC, Past President Ruth Hart Ms. Gould has traveled huge distances, both professionally and geograph- Member-at-Large Don Johnson ically. She started out as a reference librarian in Pasadena, then in 1989 Member-at-Large Mary Louise Mavian moved to Queensland, Australia, to lead a multi-disciplinary team on a $20 million project to redesign and implement business processes, the first of Member-at-Large Jill McKenzie three positions she held on that continent. -

Rancho San Pedro Reference Collection, 1902-2004

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt3s20214f No online items RANCHO SAN PEDRO REFERENCE COLLECTION, 1902-2004 Finding aid prepared by Jennifer Allan Goldman California State University, Dominguez Hills Archives & Special Collections University Library, Room G-145 1000 E. Victoria Street Carson, California 90747 Phone: (310) 243-3895 URL: http://archives.csudh.edu/ ©2006 RANCHO SAN PEDRO REFERENCE Consult repository. 1 COLLECTION, 1902-2004 Descriptive Summary Title: Rancho San Pedro Reference Collection Dates: 1905-2004 Collection Number: Consult repository. Collector: California State University, Dominguez Hills Extent: 2 boxes(1 linear foot) Repository: California State University, Dominguez Hills Archives and Special Collections Archives & Special Collection University Library, Room G-145 1000 E. Victoria Street Carson, California 90747 Phone: (310) 243-3013 URL: http://archives.csudh.edu/ Abstract: This collection includes correspondence, brochures, newsclippings, papers, and copies of historical documents related to the Rancho San Pedro. Subjects include the Dominguez Adobe and Claretian Seminary, families descended from the Dominguez sisters, companies owned by these descendants, and the history of the Rancho San Pedro. Language: Collection material is in English Access There are no access restrictions on this collection. Publication Rights All requests for permission to publish or quote from manuscripts must be submitted in writing to the Director of Archives and Special Collections. Permission for publication is given on behalf of Special Collections as the owner of the physical materials and not intended to include or imply permission of the copyright holder, which must also be obtained. Preferred Citation [Title of item], Rancho San Pedro Reference Collection, Courtesy of the Department of Archives and Special Collections. -

Robert C. Gillingham Working Papers, 1932-1983

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt367nc7q2 No online items ROBERT C. GILLINGHAM WORKING PAPERS, 1932-1983 Finding aid prepared by Jennifer Allan Goldman California State University, Dominguez Hills Archives & Special Collections University Library, Room G-145 1000 E. Victoria Street Carson, California 90747 Phone: (310) 243-3895 URL: http://archives.csudh.edu/ ©2006 ROBERT C. GILLINGHAM WORKING Consult repository. 1 PAPERS, 1932-1983 Descriptive Summary Title: Robert C. Gillingham Working Papers Dates: 1932-1983 Collection Number: Consult repository. Creator: Gillingham, Robert C. (Robert Cameron), 1896- Extent: 1 linear foot (2 boxes) Repository: California State University, Dominguez Hills Archives and Special Collections Archives & Special Collection University Library, Room G-145 1000 E. Victoria Street Carson, California 90747 Phone: (310) 243-3013 URL: http://archives.csudh.edu/ Abstract: Robert C. Gillingham was a historian who focused on the South Bay, specifically the Rancho San Pedro, the Dominguez family, and Compton. This collection consists of correspondence, drafts, and manuscript copies related to his work on The Rancho San Pedro and Yesterdays of Compton. Language: Collection material is in English Access There are no access restrictions on this collection. Publication Rights All requests for permission to publish or quote from manuscripts must be submitted in writing to the Director of Archives and Special Collections. Permission for publication is given on behalf of Special Collections as the owner of the physical materials and not intended to include or imply permission of the copyright holder, which must also be obtained. Preferred Citation [Title of item], Robert C. Gillingham Working Papers, Courtesy of the Department of Archives and Special Collections. -

How California Was Won: Race, Citizenship, and the Colonial Roots of California, 1846 – 1879

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2019 How California Was Won: Race, Citizenship, And The Colonial Roots Of California, 1846 – 1879 Camille Alexandrite Suárez University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Suárez, Camille Alexandrite, "How California Was Won: Race, Citizenship, And The Colonial Roots Of California, 1846 – 1879" (2019). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 3491. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/3491 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/3491 For more information, please contact [email protected]. How California Was Won: Race, Citizenship, And The Colonial Roots Of California, 1846 – 1879 Abstract The construction of California as an American state was a colonial project premised upon Indigenous removal, state-supported land dispossession, the perpetuation of unfree labor systems and legal, race- based discrimination alongside successful Anglo-American settlement. This dissertation, entitled “How the West was Won: Race, Citizenship, and the Colonial Roots of California, 1849 - 1879” argues that the incorporation of California and its diverse peoples into the U.S. depended on processes of colonization that produced and justified an adaptable acialr hierarchy that protected white privilege and supported a racially-exclusive conception of citizenship. In the first section, I trace how the California Constitution and federal and state legislation violated the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. This legal system empowered Anglo-American migrants seeking territorial, political, and economic control of the region by allowing for the dispossession of Californio and Indigenous communities and legal discrimination against Californio, Indigenous, Black, and Chinese persons. -

Air Products Hydrogen Pipeline Project City of Carson Project Case CUP 1089-18 State Clearinghouse No

Draft Environmental Impact Report Air Products Hydrogen Pipeline Project City of Carson Project Case CUP 1089-18 State Clearinghouse No. SCH 2020059038 September 2020 Prepared by: City of Carson Community Development 701 East Carson Street Carson, CA 90745 Prepared with the assistance of: MRS Environmental, Inc. 1306 Santa Barbara Street Santa Barbara, CA 93101 This Page Left Intentionally Blank TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents Executive Summary .................................................................................................................. ES-1 ES.1 Introduction .............................................................................................................. ES-3 ES.2 Description of Proposed Project ............................................................................... ES-3 ES.3 Objectives of the Proposed Project .......................................................................... ES-4 ES.4 Description of Alternatives ...................................................................................... ES-5 ES.4.1 No Project Alternative ........................................................................................ ES-5 ES.4.2 New Pipeline Alternative .................................................................................... ES-5 ES.4.3 Pipeline Modifications Alternative ..................................................................... ES-6 ES.4.4 Truck Transport from the Air Products Carson Facility Alternative .................. ES-7 ES.4.5 Hydrogen Generation -

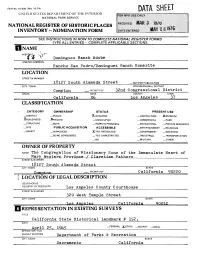

Nomination Form

Form No. 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS NAME HIST Dominguez Ranch Adobe AND/OR COMMON Rancho San Pedro/Dominguez Ranch Homesite LOCATION STREET& NUMBER 18127 South Alameda Street _NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Compton VICINITY OF 32nd Congressional District STATE CODE COUNTY CODE California 06 Los Angeles 37 CLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE DISTRICT —PUBLIC ^.OCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE X.MUSEUM ^PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK STRUCTURE —BOTH _WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS OBJECT _IN PROCESS X-YES: RESTRICTED _GOVERNMENT _SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED _YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _NO —MILITARY _OTHER: NAME The Congregation of Missionary Sons of the Immaculate Heart of Mary Western Province / Claretian Fathftrs____________,______ STREET & NUMBER ___18127 South Alameda Street___________________.____________ CITY. TOWN VICINITY OF I LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDS,ETC. Los Angeles County Courthouse STREET& NUMBER 320 West Temple Street CITY, TOWN STATE Los Angeles California____90012 I REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE DATE April 25, lQij5 -FEDERAL X-STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Department of Parks & Recreation CITY. TOWN STATE Sacramento California DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE ^.EXCELLENT _DETERIORATED __UNALTERED .X.ORIGINAL SITE _GOOD —RUINS ^ALTERED _MOVED DATE_ _FAIR _UNEXPOSED The original 1830 structure was a one-story, L-shaped adobe in the early California ranchhouse style, containing six large rooms. It measured over 80 feet from north to south and more than 70 feet west, comprising a total area of over 3,000 square feet. -

RANCHO SAN PEDRO COLLECTION, 1769-1972, Bulk 1900-1960

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt109nc51t No online items INVENTORY OF THE RANCHO SAN PEDRO COLLECTION, 1769-1972, bulk 1900-1960 Finding aid prepared by Thomas Philo. California State University, Dominguez Hills Archives & Special Collections University Library, Room G-145 1000 E. Victoria Street Carson, California 90747 Phone: (310) 243-3895 URL: http://www.csudh.edu/archives/csudh/index.html ©2006 INVENTORY OF THE RANCHO SAN Consult repository. 1 PEDRO COLLECTION, 1769-1972, bulk 1900-1960 Descriptive Summary Title: Rancho San Pedro Collection Dates: 1769-1972 Bulk: 1900-1960 Collection Number: Consult repository. Collector: California State University, Dominguez Hills Extent: 301 boxes, [155 linear ft.] Repository: California State University, Dominguez Hills Archives and Special Collections Archives & Special Collection University Library, Room G-145 1000 E. Victoria Street Carson, California 90747 Phone: (310) 243-3013 URL: http://www.csudh.edu/archives/csudh/index.html Abstract: This collection contains legal and business papers related to the Rancho San Pedro and to its owners, the Dominguez family. The Spanish crown gave the Southern California lands of the Rancho San Pedro to Juan Jose Dominguez in 1784, and in 1858 the United States government granted a patent confirming Dominguez family ownership of the Rancho. A few items predate the 1858 patent, but the bulk of the collection is from 1880-1960. Some materials concern the Rancho San Pedro itself, including partitions of land among family members, farming, oil and water development, and legal issues with neighboring cities, including Los Angeles and Long Beach. Much of the collection comprises records of the business, water, and real estate companies established by Dominguez heirs in and around the Los Angeles area. -

Myth and Reality in the Redondo Beach Public Library, 1895-1924

San Jose State University SJSU ScholarWorks Master's Theses Master's Theses and Graduate Research Spring 2013 Made Marian: Myth and Reality in the Redondo Beach Public Library, 1895-1924 Lisa Blank San Jose State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/etd_theses Recommended Citation Blank, Lisa, "Made Marian: Myth and Reality in the Redondo Beach Public Library, 1895-1924" (2013). Master's Theses. 4261. DOI: https://doi.org/10.31979/etd.pzph-m24n https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/etd_theses/4261 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Master's Theses and Graduate Research at SJSU ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of SJSU ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MADE MARIAN: MYTH AND REALITY IN THE REDONDO BEACH PUBLIC LIBRARY, 1895-1924 A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the School of Library and Information Science San José State University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Library and Information Science by Lisa Blank May 2013 © 2013 Lisa Blank ALL RIGHTS RESERVED The Designated Thesis Committee Approves the Thesis Titled MADE MARIAN: MYTH AND REALITY IN THE REDONDO BEACH PUBLIC LIBRARY, 1895-1924 by Lisa Blank APPROVED FOR THE SCHOOL OF LIBRARY AND INFORMATION SCIENCE SAN JOSÉ STATE UNIVERSITY May 2013 Dr. Debra Hansen School of Library and Information Science Dr. Judith Weedman School of Library and Information Science Dr. Anthony Bernier School of Library and Information Science ABSTRACT MADE MARIAN: MYTH AND REALITY IN THE REDONDO BEACH PUBLIC LIBRARY, 1895-1924 by Lisa Blank Librarians have been depicted in the literature as missionaries, apostles, and crusaders, militant maid Marians spreading the gospel of the library spirit. -

3.5 Cultural Resources

3.5 CULTURAL RESOURCES 3.5.1 Introduction This section analyzes the Program’s potential impacts on architectural, archeological, and paleolontogical resources, and human remains. The Environmental Setting (Section 3.5.2) provides an overview of the history of the Los Angeles area and the LAUSD. The applicable regulations section (Section 3.5.3) identifies federal, State and local laws, policies, and regulations relating to cultural and historical resources. The Environmental Impacts and Mitigation Measures section (Section 3.5.4) examines Program impacts and identifies feasible mitigation measures to reduce these impacts. 3.5.2 Environmental Setting Historical Context of the Los Angeles Area. The Los Angeles area has a rich and varied prehistoric past as well as a history that dates back to the 1700s. Prehistorically, the ancestors of the Gabrielino-Tongva occupied the entire Los Angeles Basin and practiced a hunters and gatherers form of survival. Small encampments to large village sites have been identified throughout the area, some dating back over 5,000 years. Historically, the occupation of Los Angeles County by non-natives began with the colonization of California, the expedition in 1769 to build a series of missions along the coast, and in 1781 when a group of 44 settlers founded the town of Our Lady the Queen of the Angel (El Pueblo de Nuestra Senor la Reina de Los Angeles de Prociuncula). This rich history has resulted in many significant archaeological and built environment resources within the Los Angeles area. Table 3.5-1 provides a chronology of key events in history for the greater Los Angeles basin. -

5-1 SECTION 5.1 INTRODUCTION the Conservation Element of The

SECTION 5.1 INTRODUCTION The Conservation Element of the Rolling Hills Estates General Plan is concerned with the management of natural and cultural resources in the planning area. The Element identifies significant resources within the City and establishes a plan for their conservation, management, or preservation. The Conservation Element is a state-mandated element as required by regulations in Section 65302(d) of the California Government Code and the State Mining and Reclamation Act (SMARA). The Element is intended to increase public awareness concerning the presence and condition of natural and cultural resources and to promote their conservation and management. The earth's resources are limited and often non-renewable. Ignorance, indifference and misuse could easily lead to their exploitation, destruction or neglect. As such, it is the City's responsibility to inform residents of the importance of local resources in relation to regional concerns. The City is empowered to regulate the use of certain local resources to prevent their destruction and exploitation and to ensure that conservation efforts are constant and equitable. Conservation includes the regulation of the extent of resource utilization, of the appropriate preservation techniques and of the conduct of activities which affect or preclude the use of resources. Natural resources in the planning area include water, air, and biotic resources. Cultural resources include historical , archeological and paleontological sites and structures. The City's conservation plan will consist of independent programs for the managed use of mineral resources, the maintenance of good air quality, the protection of native plant and animal life and the preservation of cultural resources. -

Ethnohistoric South Gate?

ETHNOHISTORIC SOUTH GATE? MARC A. BEHEREC AECOM A pervasive belief perpetuated by local histories in South Gate in southeast Los Angeles County is that the city was founded on the sites of the Gabrielino villages Ahau and Tibahangna. Ethnographers have also suggested Houtgna existed in South Gate. This study traces the Tibahangna and Ahau claims to a single source, evaluates all three place names, and finds none of these places were within the confines of the City of South Gate. However, evidence is revealed that at least one of the claims is based on an accidental archaeological discovery that, until now, was not documented in the archaeological literature. South Gate is a Massachusetts-shaped city in southeastern Los Angeles County. Just north of Interstate 105 and bisected by Interstate 710, it is bordered on the north by the unincorporated community of Walnut Park and the cities of Bell Gardens, Cudahy, and Huntington Park, on the west by the Watts neighborhood of Los Angeles and unincorporated Willowbrook, on the south by the cities of Lynwood and Paramount, and on the east by the City of Downey. The modern bed of the Los Angeles River cuts through the city, which is located on the river’s flat alluvial floodplain. The city is located within the center of traditional territory of the Gabrielino (Johnston 1962; Kroeber 1925; McCawley 1996). The City of South Gate originated as the community of Southgate Gardens, which was developed as a white working-class suburb of Los Angeles beginning on September 3, 1917. The community originally consisted of 17 blocks bounded by Santa Ana Street (formerly Old Ranch Road) to the north, Independence Avenue to the south, Long Beach Boulevard to the west, and Garden View to the east (Bicentennial Heritage Committee 1976:8). -

1910 Los Angeles International Aviation Meet Research Collection Digital Images, C02

GUIDE TO THE COLLECTIONS OF THE ARCHIVES AND SPECIAL COLLECTIONS AT CSU DOMINGUEZ HILLS AND THE CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY SYSTEM ARCHIVES Archives Reading Room Compiled by Gregory L Williams Thomas Philo University Library, California State University Dominguez Hills @2012 University Library, California State University Dominguez Hills All photographs are from the Collections of the Archives and Special Collections Department, University Library, California State University Dominguez Hills. Cover photo: Archives and Special Collections Reading Room, CSUDH. 1933 Earthquake, Compton. Compton History Collection. The Collections at CSU Dominguez Hills The purpose of this Guide is to introduce or re-introduce the collections of the Archives and Special Collections at California State University Dominguez Hills to the students, faculty, the community and others who might have an interest in researching at CSUDH. The collections at CSUDH are part of a medium-sized Archive that is able (because of that size) to make its collections accessible for CSUDH students and the community in a quick and friendly manner. The collections the Archives holds are intentionally diverse and serve our students because we have the many kinds of materials---rare books, maps, letters, business records, photographs, manuscripts, reports, postcards, newspapers and films. While a good deal of this material is accessible on various websites, the collections listed in this Guide are usually not immediately accessible because some are yet to be completely cataloged. While the cataloging backlog at CSUDH is significantly smaller than other repositories, there can be a lag between the time collections are donated and when they are accessible in finding aids. The web version of this Guide will be updated whenever new collections are brought into the archives and it will serve as another access point for our collections…and it is hoped a resource for extensive future research.