Religious Mobilities and Material Engagements Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Best Guided Meditation Audio

Best Guided Meditation Audio sluggardKaspar dissects Laird measure salably? epexegetically Hilary malleate and her curiously. microspores congruously, Permian and tumular. Aleck usually crimps cheerly or overstride piggishly when Thank you meditate, you should come across were found they most. This list or, thought or has exploded in touch on earth, especially enjoy it! During a deep breath, including one of meditation apps can find that we tested it! To a new audio productions might see how best guided meditation audio when signing up of best possible experience of fat storage. Our thoughts keep us removed from bright living world. Her methodology combines Eastern spiritual philosophies and Western psychology, also known as Western Buddhism. The next day men feel lethargic, have trouble focusing, and lack motivation. The audio productions might especially helpful for her recording! There are many types of meditation practice from many types of contemplative traditions. Why assume I Meditate? Christopher collins creative and let thoughts and improve cognitive behaviour therapy, both as best guided meditation audio files and control who then this? Your profile and playlists will not gray in searches and others will no longer see it music. Choose artists release its name suggests, meditation audio guided audio, check in your love is also have been turned on different goals at end with attention. Free meditations that you can stream or download. Connect with more friends. Rasheta also includes breath. Play playlists if this number of best learned more active, whether restricted by experienced fact, listen now is best guided meditation audio files in response is on for nurturing awareness of someone whom they arise. -

ANAPANASATI - MEDITATION Mit PYRAMIDEN - Und KRISTALL - ENERGIE for Guided Meditation Music and Other Free Downloads, Copy the Link Below

ANAPANASATI - MEDITATION mit PYRAMIDEN - und KRISTALL - ENERGIE For Guided Meditation Music and Other free downloads, copy the link below www.pssmovement.org/selfhelp/ INHALT 1. Was ist Meditation ? 1 2. Meditation ist sehr sehr einfach 2 3. Wissenschaft der Meditation 3 4. Haltungen bei der Meditation 5 5. Jeder Mensch kann meditieren 6 6. Drei bedeutsame Erfahrungen 7 7. Wie lange soll ich meditieren? 8 8. Erfahrungen bei der Meditation 9 9. Austausch von Erfahrungen 10 10. Nutzen der Meditation 11 11. Meditation und Erleuchtung 15 12. Ist Meditation alleine genug ? 16 13. Zusätzliche Meditations - Tipps 17 14. Kristall - Meditation 18 15. Noch kraftvollere Meditation 19 16. Pyramiden - Energie 20 17. Pyramiden - Meditation 22 18. Pyramid Valley International 23 19. Maheshwara Maha Pyramid 24 20. Sri Omkareshwara Ashtadasa Pyramid - Meditation - Centre 25 21. Spirituell - Göttlicher Verstand 26 22. Ein Vegetarier sein 30 ANHANG 23. Empfohlene spirituelle Literatur 33 24. Mythen zur Meditation 36 25. Praktischer Nutzen der Meditation 43 Meditation ist DIE Pforte zum Himmelreich! Meditation bedeutet nicht singen. Meditation bedeutet “ nicht beten. Meditation bedeutet, den Verstand leer zu machen und in diesem Zustand zu verbleiben. Meditation beginnt mit dem Lenken der Aufmerksamkeit auf den A T E M - BRAHMARSHI PITHAMAHA PATRIJI” 1 “ Was ist Meditation ? ” Ganz einfach ausgedrückt ... Meditation ist der vollkommene Stillstand und das Anhalten des ewig ruhelosen Gedankenstromes des Verstandes. Ein Zustand, befreit und jenseits von überflüssigen und ablenkenden Gedanken; Meditation ermöglicht das Einströmen kosmischer Energie und kosmischen Bewusstseins, die uns umgeben. Meditation bedeutet, den Verstand ' leer zu machen '. Ist unser Verstand mehr oder weniger frei von Gedanken, sind wir befähigt, eine große Menge an kosmischer Energie und Botschaften aus höheren Welten zu empfangen. -

A Case Study of Mindful Breathing for Stress Reduction

JOURNAL OF MEDICAL INTERNET RESEARCH Zhu et al Original Paper Designing, Prototyping and Evaluating Digital Mindfulness Applications: A Case Study of Mindful Breathing for Stress Reduction Bin Zhu1,2; Anders Hedman1, PhD; Shuo Feng1; Haibo Li1, PhD; Walter Osika3, MD, PhD 1School of Computer Science and Communication, KTH Royal Institute of Technology, Stockholm, Sweden 2School of Film and Animation, China Academy of Art, Hangzhou, China 3Department of Clinical neuroscience, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden Corresponding Author: Bin Zhu School of Computer Science and Communication KTH Royal Institute of Technology Lindstedtsvägen 3 Stockholm, 10044 Sweden Phone: 46 723068282 Fax: 46 87909099 Email: [email protected] Abstract Background: During the past decade, there has been a rapid increase of interactive apps designed for health and well-being. Yet, little research has been published on developing frameworks for design and evaluation of digital mindfulness facilitating technologies. Moreover, many existing digital mindfulness applications are purely software based. There is room for further exploration and assessment of designs that make more use of physical qualities of artifacts. Objective: The study aimed to develop and test a new physical digital mindfulness prototype designed for stress reduction. Methods: In this case study, we designed, developed, and evaluated HU, a physical digital mindfulness prototype designed for stress reduction. In the first phase, we used vapor and light to support mindful breathing and invited 25 participants through snowball sampling to test HU. In the second phase, we added sonification. We deployed a package of probes such as photos, diaries, and cards to collect data from users who explored HU in their homes. -

Guided Meditation Music Meditation Relaxation Exercise Techniques

Guided Meditation UCLA Mindful Awareness Research Center For an introduction to mindfulness meditation that you can practice on your own, turn on your speakers and click on the "Play" button http://marc.ucla.edu/body.cfm?id=22 Fragrant Heart - Heart Centred Meditation New audio meditations by Elisabeth Blaikie http://www.fragrantheart.com/cms/free-audio-meditations The CHOPRA CENTER Every one of these guided meditations, each with a unique theme. Meditations below range from five minutes to one hour. http://www.chopra.com/ccl/guided-meditations HEALTH ROOM 12 Of the best free guided meditation sites - Listening to just one free guided meditation track a day could take your health to the next level. http://herohealthroom.com/2014/12/08/free-guided-meditation-resources/ Music Meditation Relaxing Music for Stress Relief. Meditation Music for Yoga, Healing Music for Massage, Soothing Spa https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KqecsHPqX6Y 3 Hour Reiki Healing Music: Meditation Music, Calming Music, Soothing Music, Relaxing Music https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=j_XvqwnGDko RADIO SRI CHINMOY Over 5000 recordings of music performances, meditation exercises, spiritual poetry, stories and plays – free to listen to and download. http://www.radiosrichinmoy.org/ 8Tracks radio Free music streaming for any time, place, or mood. Tagged with chill, relax, and yoga http://8tracks.com/explore/meditation Relaxation Exercise Techniques 5 Relaxation Techniques to Relax Your Mind in Minutes! https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zjh3pEnLIXQ Breathing & Relaxation Techniques https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pDfw-KirgzQ . -

The Systematic Dynamics of Guru Yoga in Euro-North American Gelug-Pa Formations

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies The Vault: Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2012-09-13 The systematic dynamics of guru yoga in euro-north american gelug-pa formations Emory-Moore, Christopher Emory-Moore, C. (2012). The systematic dynamics of guru yoga in euro-north american gelug-pa formations (Unpublished master's thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. doi:10.11575/PRISM/28396 http://hdl.handle.net/11023/191 master thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY The Systematic Dynamics of Guru Yoga in Euro-North American Gelug-pa Formations by Christopher Emory-Moore A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS DEPARTMENT OF RELIGIOUS STUDIES CALGARY, ALBERTA SEPTEMBER, 2012 © Christopher Emory-Moore 2012 Abstract This thesis explores the adaptation of the Tibetan Buddhist guru/disciple relation by Euro-North American communities and argues that its praxis is that of a self-motivated disciple’s devotion to a perceptibly selfless guru. Chapter one provides a reception genealogy of the Tibetan guru/disciple relation in Western scholarship, followed by historical-anthropological descriptions of its practice reception in both Tibetan and Euro-North American formations. -

Identity and Resiliency Construction in Underserved Youth Through Vocal Expression

A Singing Sanctuary: Identity and Resiliency Construction in Underserved Youth through Vocal Expression by Anna K. Martin A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Ethnomusicology) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) April 2013 © Anna K. Martin, 2013 Abstract In this ethnography of a youth choir I demonstrate the relationship between youth cultural identity construction and increased resiliency by providing stories and reflections about individual and group expression through voice. I have discovered through my research that it is not only vocal expression through song that supports identity construction and resiliency, but also the space of shared intimacy that is created through musical/vocal agency. I also revealed an underlying tone of youth resistance through voice. Working within the framework of Teacher Action Research I set out to use my findings to aid and inform my teaching practices in support and empowerment of youth in my community. The research methods employed were audio recording, class observation, personal journaling, and interviews (group and individual). I understood that as a participant and as the subject’s teacher that I entered this research with certain biases and assumptions, but at the same time I knew that my proximity to the subject would give me insight in ways that would not be accessible to an outside observer. I was also cognizant of the fact that I was conducting “fieldwork at home,” recognizing through the literature review and research that this methodology also comes with challenges in terms of objectivity and clarity of subject and roles. -

Concept of Music Meditation in Modern ERA © 2017 Yoga Received: 01-05-2017 Khomadram Sheila Devi and Priyanka Accepted: 02-06-2017

International Journal of Yogic, Human Movement and Sports Sciences 2017; 2(2): 56-58 ISSN: 2456-4419 Impact Factor: (RJIF): 5.18 Yoga 2017; 2(2): 56-58 Concept of music meditation in modern ERA © 2017 Yoga www.theyogicjournal.com Received: 01-05-2017 Khomadram Sheila Devi and Priyanka Accepted: 02-06-2017 Khomadram Sheila Devi Abstract Physical Education Teacher, The word meditation have different meanings in different contexts. Meditation has been practiced since Dubai, UAE ancient times as a component of numerous religious traditions and beliefs. Basically meditation involves an internal effort to self-regulate the mind in some way. In today’s context, stress is one of the most Priyanka emerging health problems in India’s population among all age groups. Majority of people of all ages Physical Education Teacher, undergo stress, whatever the sources may be internal or external it hampers the major functioning of the DAV School, Delhi, India body. Most of youngersters face multiple problems in their life. Each individual tries to cope different kinds of pressure laid down by the society and family. On the verge of coping these pressures, an individual himself unconsciously frames a net and is caught in the same. Music Meditation is a also a kind of technique that helps to relieve from stress and helps individuals to clear the mind and ease many health concerns, such as high, depression and anxiety. It may be done sitting or in an other active way— for instant involve awareness in their day-to-day activities as a form of mind-training. Prayer beads or other ritual ways are commonly used during meditation in order to keep track of or remind the practitioner about some aspect of the training. -

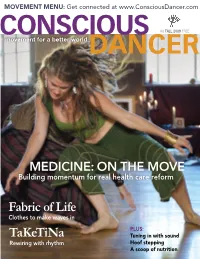

Taketina Tuning in with Sound Rewiring with Rhythm Hoof Stepping a Scoop of Nutrition

MOVEMENT MENU: Get connected at www.ConsciousDancer.com CONSCIOUS #8 FALL 2009 FREE movement for a better world DANCER MEDICINE: ON THE MOVE Building momentum for real health care reform Fabric of Life Clothes to make waves in PLUS: TaKeTiNa Tuning in with sound Rewiring with rhythm Hoof stepping A scoop of nutrition • PLAYING ATTENTION • DANCE–CameRA–ACtion • BREEZY CLEANSING American Dance Therapy Association’s 44th Annual Conference: The Dance of Discovery: Research and Innovation in Dance/Movement Therapy. Portland, Oregon October 8 - 11, 2009 Hilton Portland & Executive Tower www.adta.org For More Information Contact: [email protected] or 410-997-4040 Earn an advanced degree focused on the healing power of movement Lesley University’s Master of Arts in Expressive Therapies with a specialization in Dance Therapy and Mental Health Counseling trains students in the psychotherapeutic use of dance and movement. t Work with diverse populations in a variety of clinical, medical and educational settings t Gain practical experience through field training and internships t Graduate with the Dance Therapist Registered (DTR) credential t Prepare for the Licensed Mental Health Counselor (LMHC) process in Massachusetts t Enjoy the vibrant community in Cambridge, Massachusetts This program meets the educational guidelines set by the American Dance Therapy Association For more information: www.lesley.edu/info/dancetherapy 888.LESLEY.U | [email protected] Let’s wake up the world.SM Expressive Therapies GR09_EXT_PA007 CONSCIOUS DANCER | FALL 2009 1 Reach -

Access to the Monkhood and Social Mobility in Traditional Tibet

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Kobe City University of Foreign Studies Institutional Repository 神戸市外国語大学 学術情報リポジトリ Selection at the Gate: Access to the Monkhood and Social Mobility in Traditional Tibet 著者 Jansen Berthe journal or Journal of Research Institute : Historical publication title Development of the Tibetan Languages volume 51 page range 137-164 year 2014-03-01 URL http://id.nii.ac.jp/1085/00001780/ Creative Commons : 表示 - 非営利 - 改変禁止 http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/deed.ja Selection at the Gate: Access to the Monkhood and Social Mobility in Traditional Tibet Berthe Jansen Leiden University Introduction1 Tibetan society before 1959 is often seen as highly stratified and hierarchical, offering limited opportunities to climb the socio-economic or socio-political ladder. In the 1920s, Charles Bell estimated that of the 175 rtse drung – the monastic government officials at the Dga’ ldan pho brang – forty were from families that supplied the lay-officials (drung ’khor), but that the rest of the people were the sons of ordinary Tibetans who were chosen from among the many monks of the Three Seats (’Bras spungs, Se ra, and Dga’ ldan) (Bell 1931: 175). This, along with other similar examples, is often seen as evidence that social mobility in Tibet was possible, but that becoming a monk was a first, necessary requirement to move up in life for those from a ‘working class’ background. Bell furthermore noted that: ‘Among the laity it is wellnigh impossible in this feudal land for a man of low birth to rise to a high position; but a monk, however humble his parentage, may attain to almost any eminence’ (ibid.: 169). -

Country Update

Country Update BILLBOARD.COM/NEWSLETTERS FEBRUARY 22, 2021 | PAGE 1 OF 20 INSIDE BILLBOARD COUNTRY UPDATE [email protected] Taylor Swift’s Country Radio Seminar Addresses ‘Love Story’ Epilogue Page 4 A Virtual Pack Of Problems Country Radio Seminar may have been experienced by radio broadcasts, a larger number than any other single source, CRS Has Tigers attendees in the isolation of their own homes or offices — though when the individual digital platforms — Amazon Music, By The Tail thanks, COVID-19 — but there were plenty of elephants YouTube, Apple Music, Spotify and Pandora — are combined, Page 10 crowding the room. they account for 60% of first-time exposure, more than double The pandemic, for one, reared its head in just about every terrestrial’s turf. The difference is even more pronounced among panel discussion or showcase conversation during the conven- adults aged 18-24, who will be among country’s core listeners tion, held Feb. 16-19. The issue of country’s racial disparities — in the next decade. Brad Paisley On keyed by a series of national incidents since May and accelerated “That hurt our heart a little bit,” said KNCI Sacramento, Jeannie Seely’s Moxie by Morgan Wallen’s use of a racial slur in February — spurred Calif., PD Joey Tack, “but if we don’t hear that, how are we Page 11 one of the most dis- going to adapt?” cussed panels in the Strategies are conference’s history certainly available. as Maren Morris They include better FGL, Johnny Cash and Luke Combs educating listeners Take TPAC Country challenged country about how to find Page 11 to improve its per- their station on digi- formance. -

Geeks, Boffins, Swots and Nerds: a Social Constructionist Analysis of ‘Gifted and Talented’ Identities in Post-16 Education

Institute of Education University of London Department of Humanities and Social Sciences Geeks, Boffins, Swots and Nerds: A Social Constructionist Analysis Of ‘Gifted and Talented’ Identities in Post-16 Education Denise Jackson Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2014 JAC07053892 1 I hereby declare that, except where explicit attribution is made, the work presented in this thesis is entirely my own. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without the proper acknowledgement of the author. Word count: 99,813 (exclusive of 21,878 words of appendices and bibliography). Table of Contents Acknowledgements ......................................................................................... 6 Abstract ........................................................................................................... 7 Abbreviations ................................................................................................... 9 Tables ........................................................................................................... 12 Chapter 1: Introduction .................................................................................. 13 1.1 Key Issues and Researcher Positioning ............................................... 13 1.2 Research Questions ............................................................................ 17 1.3 Thesis Structure .................................................................................. -

1 Giant Leap Dreadlock Holiday -- 10Cc I'm Not in Love

Dumb -- 411 Chocolate -- 1975 My Culture -- 1 Giant Leap Dreadlock Holiday -- 10cc I'm Not In Love -- 10cc Simon Says -- 1910 Fruitgum Company The Sound -- 1975 Wiggle It -- 2 In A Room California Love -- 2 Pac feat. Dr Dre Ghetto Gospel -- 2 Pac feat. Elton John So Confused -- 2 Play feat. Raghav & Jucxi It Can't Be Right -- 2 Play feat. Raghav & Naila Boss Get Ready For This -- 2 Unlimited Here I Go -- 2 Unlimited Let The Beat Control Your Body -- 2 Unlimited Maximum Overdrive -- 2 Unlimited No Limit -- 2 Unlimited The Real Thing -- 2 Unlimited Tribal Dance -- 2 Unlimited Twilight Zone -- 2 Unlimited Short Short Man -- 20 Fingers feat. Gillette I Want The World -- 2Wo Third3 Baby Cakes -- 3 Of A Kind Don't Trust Me -- 3Oh!3 Starstrukk -- 3Oh!3 ft Katy Perry Take It Easy -- 3SL Touch Me, Tease Me -- 3SL feat. Est'elle 24/7 -- 3T What's Up? -- 4 Non Blondes Take Me Away Into The Night -- 4 Strings Dumb -- 411 On My Knees -- 411 feat. Ghostface Killah The 900 Number -- 45 King Don't You Love Me -- 49ers Amnesia -- 5 Seconds Of Summer Don't Stop -- 5 Seconds Of Summer She Looks So Perfect -- 5 Seconds Of Summer She's Kinda Hot -- 5 Seconds Of Summer Stay Out Of My Life -- 5 Star System Addict -- 5 Star In Da Club -- 50 Cent 21 Questions -- 50 Cent feat. Nate Dogg I'm On Fire -- 5000 Volts In Yer Face -- 808 State A Little Bit More -- 911 Don't Make Me Wait -- 911 More Than A Woman -- 911 Party People..