Selected Video Essays, 2004-16

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

This Item Is the Archived Peer-Reviewed Author-Version Of

This item is the archived peer-reviewed author-version of: Periodizing Samuel Beckett's Works A Stylochronometric Approach Reference: Van Hulle Dirk, Kestemont Mike.- Periodizing Samuel Beckett's Works A Stylochronometric Approach Style - ISSN 0039-4238 - 50:2(2016), p. 172-202 Full text (Publisher's DOI): https://doi.org/10.1353/STY.2016.0003 To cite this reference: http://hdl.handle.net/10067/1382770151162165141 Institutional repository IRUA This is the author’s version of an article published by the Pennsylvania State University Press in the journal Style 50.2 (2016), pp. 172-202. Please refer to the published version for correct citation and content. For more information, see http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5325/style.50.2.0172?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents. <CT>Periodizing Samuel Beckett’s Works: A Stylochronometric Approach1 <CA>Dirk van Hulle and Mike Kestemont <AFF>UNIVERSITY OF ANTWERP <abs>ABSTRACT: We report the first analysis of Samuel Beckett’s prose writings using stylometry, or the quantitative study of writing style, focusing on grammatical function words, a linguistic category that has seldom been studied before in Beckett studies. To these function words, we apply methods from computational stylometry and model the stylistic evolution in Beckett’s oeuvre. Our analyses reveal a number of discoveries that shed new light on existing periodizations in the secondary literature, which commonly distinguish an “early,” “middle,” and “late” period in Beckett’s oeuvre. We analyze Beckett’s prose writings in both English and French, demonstrating notable symmetries and asymmetries between both languages. The analyses nuance the traditional three-part periodization as they show the possibility of stylistic relapses (disturbing the linearity of most periodizations) as well as different turning points depending on the language of the corpus, suggesting that Beckett’s English oeuvre is not identical to his French oeuvre in terms of patterns of stylistic development. -

Rape and the Virgin Spring Abstract

Silence and Fury: Rape and The Virgin Spring Alexandra Heller-Nicholas Abstract This article is a reconsideration of The Virgin Spring that focuses upon the rape at the centre of the film’s action, despite the film’s surface attempts to marginalise all but its narrative functionality. While the deployment of this rape supports critical observations that rape on-screen commonly underscores the seriousness of broader thematic concerns, it is argued that the visceral impact of this brutal scene actively undermines its narrative intent. No matter how central the journey of the vengeful father’s mission from vengeance to redemption is to the story, this ultimately pales next to the shocking impact of the rape and murder of the girl herself. James R. Alexander identifies Ingmar Bergman’s The Virgin Spring as “the basic template” for the contemporary rape-revenge film[1 ], and despite spawning a vast range of imitations[2 ], the film stands as a major entry in the canon of European art cinema. Yet while the sumptuous black and white cinematography of long-time Bergman collaborator Sven Nykvist combined with lead actor Max von Sydow’s trademark icy sobriety to garner it the Academy Award for Best Foreign film in 1960, even fifty years later the film’s representation of the rape and murder of a young girl remain shocking. The film evokes a range of issues that have been critically debated: What is its placement in a more general auteurist treatment of Bergman? What is its influence on later rape-revenge films? How does it fit into a broader understanding of Swedish national cinema, or European art film in general? But while the film hinges around the rape and murder, that act more often than not is of critical interest only in how it functions in these more dominant debates. -

Customizable • Ease of Access Cost Effective • Large Film Library

CUSTOMIZABLE • EASE OF ACCESS COST EFFECTIVE • LARGE FILM LIBRARY www.criterionondemand.com Criterion-on-Demand is the ONLY customizable on-line Feature Film Solution focused specifically on the Post Secondary Market. LARGE FILM LIBRARY Numerous Titles are Available Multiple Genres for Educational from Studios including: and Research purposes: • 20th Century Fox • Foreign Language • Warner Brothers • Literary Adaptations • Paramount Pictures • Justice • Alliance Films • Classics • Dreamworks • Environmental Titles • Mongrel Media • Social Issues • Lionsgate Films • Animation Studies • Maple Pictures • Academy Award Winners, • Paramount Vantage etc. • Fox Searchlight and many more... KEY FEATURES • 1,000’s of Titles in Multiple Languages • Unlimited 24-7 Access with No Hidden Fees • MARC Records Compatible • Available to Store and Access Third Party Content • Single Sign-on • Same Language Sub-Titles • Supports Distance Learning • Features Both “Current” and “Hard-to-Find” Titles • “Easy-to-Use” Search Engine • Download or Streaming Capabilities CUSTOMIZATION • Criterion Pictures has the rights to over 15000 titles • Criterion-on-Demand Updates Titles Quarterly • Criterion-on-Demand is customizable. If a title is missing, Criterion will add it to the platform providing the rights are available. Requested titles will be added within 2-6 weeks of the request. For more information contact Suzanne Hitchon at 1-800-565-1996 or via email at [email protected] LARGE FILM LIBRARY A Small Sample of titles Available: Avatar 127 Hours 2009 • 150 min • Color • 20th Century Fox 2010 • 93 min • Color • 20th Century Fox Director: James Cameron Director: Danny Boyle Cast: Sam Worthington, Sigourney Weaver, Cast: James Franco, Amber Tamblyn, Kate Mara, Michelle Rodriguez, Zoe Saldana, Giovanni Ribisi, Clemence Poesy, Kate Burton, Lizzy Caplan CCH Pounder, Laz Alonso, Joel Moore, 127 HOURS is the new film from Danny Boyle, Wes Studi, Stephen Lang the Academy Award winning director of last Avatar is the story of an ex-Marine who finds year’s Best Picture, SLUMDOG MILLIONAIRE. -

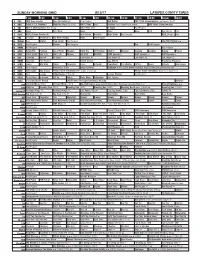

Sunday Morning Grid 8/13/17 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 8/13/17 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program Bull Riding 2017 PGA Championship Final Round. (N) Å 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) NBC4 News Paid Triathlon From Kailua-Kona, Hawaii. IAAF World Championships 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News News News Paid Eye on L.A. Paid 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Mike Webb Paid Program REAL-Diego Paid 11 FOX In Touch Invitation to Fox News Sunday News Paid Program 13 MyNet Paid Matter Fred Jordan Paid Program The Pink Panther ›› 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Paid Program The Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Paint With Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Kitchen Mexican Cooking Cooking Baking Project 28 KCET 1001 Nights Bali (TVG) Bali (TVG) Edisons Biz Kid$ Biz Kid$ KCET Special Å KCET Special Å KCET Special Å 30 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Law Order: CI Law Order: CI Law Order: CI Law Order: CI 34 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Fútbol Central Liga MX (N) República Deportiva 40 KTBN James Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Jeffress Super Kelinda John Hagee 46 KFTR Paid Program Recuerda y Gana Juego Estrellas Gladiator ››› (2000, Drama Histórico) Russell Crowe, Joaquin Phoenix. -

Factsheet the Netherlands and the European Audiovisual Sector

25 years of MEDIA Factsheet The Netherlands and the European audiovisual sector MEDIA budget invested in The Netherlands (2007-2015): €42.4 million Since 1991, MEDIA has provided support to strengthen Europe’s audiovisual sector, including the film, TV and videogames industries, so that it can creatively convey the breadth of Europe’s rich cultural diversity to audiences around the world. Over €2.4 billion has been invested in enhancing the careers of audiovisual professionals and in giving new audiences access to Europe’s wealth of creative and cultural achievements in cinemas, on TV and on digital platforms. EXAMPLES of success stories Many Dutch projects have benefited from the help of the MEDIA programme: CineMart - International Film Festival Rotterdam (2007-2015: €1,950,000) – Market Access IDFA Bertha Fund-Europe - St. Jan Vrijman Fonds (2014-2015: €620,000) – International Coproduction Funds DocsOnline (2007-2015: €1,085,000) – Online Distributie … Paradise Now! (2005) Kauwboy (2012) Fish Tank (2009) Best Foreign Language Film Best First Feature at the Berlinale Jury Prize Award at Cannes Festival at Golden Globe awards European Discovery - Prix Fipresci Alexander Korda Award for Best British Nominated for the Academy Award at European Film Awards Film at BAFTA awards for Best Foreign Language Film Cinekid is supported through the calls for Festivals, Market Access, Audience Development and Training and this enables them to support the whole audiovisual chain: from script development, co-production, distribution/acquisition to knowledge exchange. This is of vital importance in a rapidly changing media landscape. Thanks to the MEDIA support, Cinekid can focus on cultural diversity and artistic quality. -

Zum Download Des Heftes Bitte Anklicken

DREIGROSCHENHEFT INFORMATIONEN ZU BERTOLT BRECHT EINZELHEFT 19. JAHRGANG 3,– EURO HEFT 1/2012 BRECHT FESTIVAL IN AUGSBURG: DAS PROGRAMM DIE „STANDARTE DES MITLEIDS“ – GEFUNDEN REPLIKEN ZU RUTH BERLAU REGINE LUTZ (FOTO) IM ARCHIV DER ADK Brechtshop_Anzeige-3GH 12.01.2010 11:48 Uhr Seite 1 Brecht Shop FÓR3IEIM3TADTRAT „Das Denken gehört zu den größten Vergnügungen _NDERE der menschlichen Rasse.“ DIE7ELT Bertolt Brecht SIE Hier erhalten Sie alle lieferbaren Bücher, BRAUCHTES"ERTOLT"RECHT CDs, DVDs, Hörbücher und die berühmte Spieluhr zur Dreigroschenoper. 30$ 3TADTRATSFRAKTION!UGSBURG 2ATHAUS!UGSBURG4EL &AX Brecht Shop · Obstmarkt 11 · 86152 Augsburg · Telefon (0821) 518804 INFO SPD FRAKTION AUGSBURGDEWWWSPD FRAKTION AUGSBURGDE www.brechtshop.de · E-Mail: [email protected] Anz_Brecht_SPD_A5.indd 1 12.03.2009 9:34:14 Uhr INHALT Editorial .. .2 FREUNDSCHAFT Impressum. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 2 Betreff:.Artikel.über.Ruth.Berlau .. 28 Von Barbara Brecht-Schall BRECHT FESTIVAL AUGSBURG 2012 Borderline.ist.nicht.ehrabschneidend. .. .. .. 29 Brecht.heute . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 3 Ein.Arzt.der.Charité.erinnert.sich.an.. Was.Brecht.für.mich.heute.bedeutet? Ruth.Berlau.und.Bertolt.Brecht.. 33 Von Gregor Gysi Von Sabine Kebir Programm-Übersicht.. Anregungen.zu.den.Ausführungen.von.Hilda. Brecht.Festival.Augsburg.2012. .. .. .. .. .. .. 6 Hoffmann. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 35 Interview.mit.David.Benjamin.Brückel. .. .. .. 8 Von Will Sebode „Maßnahme“.und.„Augsburger.Kreidekreis“.. beim.Brecht.Festival.Augsburg.2012:.. BRECHT UND KUNST Der.Regisseur.gibt.Auskunft „Der.Herr.der.Fische“.aus.Buenos.Aires.. 36 Von Volkmar Häußler BRECHT UND MUSIK Die.Standarte.des.Mitleids.–.gefunden . .. .. .. 11 BRECHTARCHIV Von Mautpreller und Joachim Lucchesi Regine.Lutz.im.Archiv.der.AdK. .. .. .. .. .. 38 KLEINE HINWEISE (III) Regine.Lutz. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 39 Von Klaus Völker 1 ..Brechts.„Aufruf.für.Henri.Guilbeaux“. -

Oral History Interview with Senga Nengudi, 2013 July 9-11

Oral history interview with Senga Nengudi, 2013 July 9-11 Funding for this interview was provided by Stoddard-Fleischman Fund for the History of Rocky Mountain Area Artists. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a recorded interview with Senga Nengudi on 2013 July 9 and 11. The interview took place in Denver, Colorado, and was conducted by Elissa Auther for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. This interview is part of the Stoddard-Fleischman Fund for the History of Rocky Mountain Area Artists Oral History Project. Senga Nengudi and Elissa Auther have reviewed the transcript. The transcript has been heavily edited. Many of their corrections and emendations appear below in brackets with initials. This transcript has been lightly edited for readability by the Archives of American Art. The reader should bear in mind that they are reading a transcript of spoken, rather than written, prose. Interview ELISSA AUTHER: This is Elissa Auther interviewing Senga Nengudi at the University of Colorado, in Colorado Springs, Colorado, on July 9, 2013, for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Senga, when did you know you wanted to become an artist? SENGA NENGUDI: I'm not, to be honest, sure, because I had two things going on: I wanted to dance and I wanted to do art. My earliest remembrance is in elementary school—I don't know if I was in the fourth or fifth grade—but in class, I had done a clay dog. -

The Evocation of the Physical, Metaphysical, and Sonic Landscapes in Samuel Beckett's Short Dramatic Works

Trinity College Trinity College Digital Repository Senior Theses and Projects Student Scholarship Spring 2012 The Evocation of the Physical, Metaphysical, and Sonic Landscapes in Samuel Beckett's Short Dramatic Works Theresa A. Incampo Trinity College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/theses Part of the Dramatic Literature, Criticism and Theory Commons, Performance Studies Commons, and the Theatre History Commons Recommended Citation Incampo, Theresa A., "The Evocation of the Physical, Metaphysical, and Sonic Landscapes in Samuel Beckett's Short Dramatic Works". Senior Theses, Trinity College, Hartford, CT 2012. Trinity College Digital Repository, https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/theses/209 The Evocation of the Physical, Metaphysical and Sonic Landscapes within the Short Dramatic Works of Samuel Beckett Submitted by Theresa A. Incampo May 4, 2012 Trinity College Department of Theater and Dance Hartford, CT 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements 5 I: History Time, Space and Sound in Beckett’s short dramatic works 7 A historical analysis of the playwright’s theatrical spaces including the concept of temporality, which is central to the subsequent elements within the physical, metaphysical and sonic landscapes. These landscapes are constructed from physical space, object, light, and sound, so as to create a finite representation of an expansive, infinite world as it is perceived by Beckett’s characters.. II: Theory Phenomenology and the conscious experience of existence 59 The choice to focus on the philosophy of phenomenology centers on the notion that these short dramatic works present the theatrical landscape as the conscious character perceives it to be. The perceptual experience is explained by Maurice Merleau-Ponty as the relationship between the body and the world and the way as to which the self-limited interior space of the mind interacts with the limitless exterior space that surrounds it. -

Deepa Mehta (See More on Page 53)

table of contents TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction Experimental Cinema: Welcome to the Festival 3 Celluloid 166 The Film Society 14 Pixels 167 Meet the Programmers 44 Beyond the Frame 167 Membership 19 Annual Fund 21 Letters 23 Short Films Ticket and Box Offce Info 26 Childish Shorts 165 Sponsors 29 Shorts Programs 168 Community Partners 32 Music Videos 175 Consulate and Community Support 32 Shorts Before Features 177 MSPFilm Education Credits About 34 Staff 179 Youth Events 35 Advisory Groups and Volunteers 180 Youth Juries 36 Acknowledgements 181 Panel Discussions 38 Film Society Members 182 Off-Screen Indexes Galas, Parties & Events 40 Schedule Grid 5 Ticket Stub Deals 43 Title Index 186 Origin Index 188 Special Programs Voices Index 190 Spotlight on the World: inFLUX 47 Shorts Index 193 Women and Film 49 Venue Maps 194 LGBTQ Currents 51 Tribute 53 Emerging Filmmaker Competition 55 Documentary Competition 57 Minnesota Made Competition 61 Shorts Competition 59 facebook.com/mspflmsociety Film Programs Special Presentations 63 @mspflmsociety Asian Frontiers 72 #MSPIFF Cine Latino 80 Images of Africa 88 Midnight Sun 92 youtube.com/mspflmfestival Documentaries 98 World Cinema 126 New American Visions 152 Dark Out 156 Childish Films 160 2 welcome FILM SOCIETY EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR’S WELCOME Dear Festival-goers… This year, the Minneapolis St. Paul International Film Festival celebrates its 35th anniversary, making it one of the longest-running festivals in the country. On this occasion, we are particularly proud to be able to say that because of your growing interest and support, our Festival, one of this community’s most anticipated annual events and outstanding treasures, continues to gain momentum, develop, expand and thrive… Over 35 years, while retaining a unique flavor and core mission to bring you the best in international independent cinema, our Festival has evolved from a Eurocentric to a global perspective, presenting an ever-broadening spectrum of new and notable film that would not otherwise be seen in the region. -

What Is a Dance? in 3 Dances, Gene Friedman Attempts to Answer Just That, by Presenting Various Forms of Movement. the Film Is D

GENE FRIEDMAN 3 Dances What is a dance? In 3 Dances, Gene Friedman attempts to answer just that, by presenting various forms of movement. The film is divided into three sections: “Public” opens with a wide aerial shot of The Museum of Modern Art’s Sculpture Garden and visitors walking about; “Party,” filmed in the basement of Judson Memorial Church, features the artists Alex Hay, Deborah Hay, Robert Rauschenberg, and Steve Paxton dancing the twist and other social dances; and “Private” shows the dancer Judith Dunn warming up and rehearsing in her loft studio, accompanied by an atonal vocal score. The three “dances” encompass the range of movement employed by the artists, musicians, and choreographers associated with Judson Dance Theater. With its overlaid exposures, calibrated framing, and pairing of distinct actions, Friedman’s film captures the group’s feverish spirit. WORKSHOPS In the late 1950s and early 1960s, three educational sites were formative for the group of artists who would go on to establish Judson Dance Theater. Through inexpensive workshops and composition classes, these artists explored and developed new approaches to art making that emphasized mutual aid and art’s relationship to its surroundings. The choreographer Anna Halprin used improvisation and simple tasks to encourage her students “to deal with ourselves as people, not dancers.” Her classes took place at her home outside San Francisco, on her Dance Deck, an open-air wood platform surrounded by redwood trees that she prompted her students to use as inspiration. In New York, near Judson Memorial Church, the ballet dancer James Waring taught a class in composition that brought together different elements of a theatrical performance, much like a collage. -

Beckett and Nothing: Trying to Understand Beckett

Introduction Beckett and nothing: trying to understand Beckett Daniela Caselli Best worse no farther. Nohow less. Nohow worse. Nohow naught. Nohow on. Said nohow on. (Samuel Beckett, Worstward Ho) In unending ending or beginning light. Bedrock underfoot. So no sign of remains a sign that none before. No one ever before so – (Samuel Beckett, The Way)1 What not On 21 April 1958 Samuel Beckett writes to Thomas MacGreevy about having written a short stage dialogue to accompany the London production of Endgame.2 A fragment of a dramatic dia- logue, paradoxically entitled Last Soliloquy, has been identifi ed as being the play in question.3 However, John Pilling, in more recent research on the chronology, is inclined to date Last Soliloquy as post-Worstward Ho and pre-What Is the Word, on the basis of a letter sent by Phyllis Carey to Beckett on 3 February 1986, on the reverse of which we fi nd jottings referring to the title First Last Words with material towards Last Soliloquy.4 If we accept this new dating hypothesis, the manuscripts of this text (UoR MS 2937/1–3) – placed between two late works often associated with nothing – indicate two speakers, P and A (tentatively seen by Ruby Cohn as Protagonist and Antagonist) and two ways in which they can deliver their lines, D for declaim and A (somewhat confusingly) for normal.5 Unlike Cohn, I read A and P as standing for ‘actor’ and ‘prompter’, thus explaining why the text is otherwise puzzlingly entitled a soliloquy and supporting her hypothesis that the lines Daniela Caselli - 9781526146458 Downloaded from manchesterhive.com at 09/25/2021 06:16:53AM via free access 2 Beckett and nothing ‘Fuck the author. -

Innovators: Filmmakers

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES INNOVATORS: FILMMAKERS David W. Galenson Working Paper 15930 http://www.nber.org/papers/w15930 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 April 2010 The views expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer- reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official NBER publications. © 2010 by David W. Galenson. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. Innovators: Filmmakers David W. Galenson NBER Working Paper No. 15930 April 2010 JEL No. Z11 ABSTRACT John Ford and Alfred Hitchcock were experimental filmmakers: both believed images were more important to movies than words, and considered movies a form of entertainment. Their styles developed gradually over long careers, and both made the films that are generally considered their greatest during their late 50s and 60s. In contrast, Orson Welles and Jean-Luc Godard were conceptual filmmakers: both believed words were more important to their films than images, and both wanted to use film to educate their audiences. Their greatest innovations came in their first films, as Welles made the revolutionary Citizen Kane when he was 26, and Godard made the equally revolutionary Breathless when he was 30. Film thus provides yet another example of an art in which the most important practitioners have had radically different goals and methods, and have followed sharply contrasting life cycles of creativity.