Volume 46, Number 3 Page 341 Summer 2018 NOTE MY ART

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New York City Adventure “One If by Land, and Two If by Sea”

NYACK COLLEGE HOMECOMING NEW YORK CITY ADVENTURE “ONE IF BY LAND, AND TWO IF BY SEA” 1 READE S T REE T WASHINGTON MARKET C PARK H G CIV I C T E URC W REE E C E N T E R O ROCKEFELLER C H A M B ERS S T REE T R PARK T E T R K R S RE A T S P N H L WE N W O N R W A RRE N S T REE T S DIS O A A M I C H E R P T T S H R I RE T 2 V E TRI B E C A N E R D AVEN W E T E N K F O R T S T R E CITY O F R A MSURRA YB ST REE T T E HALL BR E T SP W T R O RR PARK R K R O KLY ASHI A L RE O P A U N A P A R K P L A C E S P R U C E S B E D O V E R C RID N A E N G A E S T E MURR A Y S T REE T G T RE RE D D E T E T T T E T 3 Y O E W E N B T B A RCL A Y STREE T E T RE E E LL K M A E T A A N T S S T E RE E RE TRE Y T T S RE M T S R L A P E A I A C K S L L E E L H P I L D I P V ESEY S T REE T E R S T R E T A N N S T R E E T O T W G B EE A T N 4 K W W M A N ES FUL T O N STREE T FRO FU 5 H T C L D E Y T T W O RLD W O RLD T R A D E O S FINA N C I A L C E N T ER SI T E DU F N F T C E N T E R J O H N T S T R E CLI RE E T E T S O U T H S T R E E T T C O R T L A N D T Y E E E S E A P O R T Pier 17 A E M J O T A IDEN E PL H N S T A T T R W S T R R RE N O R T H L E T E E A N T T C O V E D E PEARL STRE T S A T S L I B ERT Y S T REE T LIBER FL W GREENWICH S E R T O T C H Y E R Pedestrian A U S T Bridge S I RE E T H N M CEDA R CED A R S T REE T A I M N BR AID I A S G E T N I T C E L S D A O Y T H A M E S A R S T N L R E E N E T T B AT T E R Y A S L A L B A N Y S T REE T T P O E S RE I PA R K N P U I N E S T T L R E E T T RE E P I N W E CIT Y H A E T T E RE CARLISLE S T REE T T -

Public Art Implementation Plan

City of Alexandria Office of the Arts & the Alexandria Commission for the Arts An Implementation Plan for Alexandria’s Public Art Policy Submitted by Todd W. Bressi / Urban Design • Place Planning • Public Art Meridith C. McKinley / Via Partnership Elisabeth Lardner / Lardner/Klein Landscape Architecture Table of Contents 1.0 Introduction 2.0 Vision, Mission, Goals 3.0 Creative Directions Time and Place Neighborhood Identity Urban and Natural Systems 4.0 Project Development CIP-related projects Public Art in Planning and Development Special Initiatives 5.0 Implementation: Policies and Plans Public Art Policy Public Art Implementation Plan Annual Workplan Public Art Project Plans Conservation Plan 6.0 Implementation: Processes How the City Commissions Public Art Artist Identification and Selection Processes Public Art in Private Development Public Art in Planning Processes Donations and Memorial Artworks Community Engagement Evaluation 7.0 Roles and Responsibilities Office of the Arts Commission for the Arts Public Art Workplan Task Force Public Art Project Task Force Art in Private Development Task Force City Council 8.0 Administration Staffing Funding Recruiting and Appointing Task Force Members Conservation and Inventory An Implementation Plan for Alexandria’s Public Art Policy 2 Appendices A1 Summary Chart of Public Art Planning and Project Development Process A2 Summary Chart of Public Art in Private Development Process A3 Public Art Policy A4 Survey Findings and Analysis An Implementation Plan for Alexandria’s Public Art Policy 3 1.0 Introduction The City of Alexandria’s Public Art Policy, approved by the City Council in October 2012, was a milestone for public art in Alexandria. That policy, for the first time, established a framework for both the City and private developers to fund new public art projects. -

Oral History Interview with Pietro Lazzari, 1964

Oral history interview with Pietro Lazzari, 1964 Funding for the digital preservation of this interview was provided by a grant from the Save America's Treasures Program of the National Park Service. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Interview HP: DR. HARLAN PHILLIPS PL: PIETRO LAZZARI HP: I think while we have the opportunity it's, I think, important to assess in a way what one begins with. You have at least, you know, a dual cultural view, more, probably, so what did you fall heir to in the way of luggage and baggage that you've carried? PL: Well, I do believe I was quite lucky, if we can put it this way, I was born in the last century, 1898, in Rome and not from a family were cultural marked point was strong. My father was very inventive himself, he could draw horses. He loved to walk long distances. I remember as a young boy we used to walk outside the gates of Rome in Via Solaria or toward Ostia, and he was not a very tall man but while he walked, and while he talked he grew, I thought he was very tall, and he was inspired, his chest forward because he was the bandolier, which is a sort of an elite corps in the Italian army and he volunteered very young. So going back to our walks, he was familiar with the Roman ruins and frescoes in churches particularly those churches on the outskirts of Rome. -

April 2021 TSDOI Newsletter

Table of Contents 2 Calendar of Events L IORNALE DI April Birthdays I G Annual Family Picnic 2021 Scholarships Volunteer Food Shuttle Farm Durham Bulls Cancelled TSDOI 3 Good & Welfare Food is Love – Italian Style Aprile, 2021 Bocce Tournament Book Review 4 Sons of Italy Awards Lifetime Achievement Award to Joe Mele 5 Wall Street “Charging Bull” Sculptor Arturo Di Modica Dies at 80 6 In Italy, The Coronavirus Devastates a Generation 7 The Secret Life of the Mandolin 8 Interessante Italian Web Sites, Food, Culture and Places Ciao Italia PBS Italian Language Foundation Flash Mob – Italian Grocery Store The Abruzzo & Molise Heritage Society of DC Crazy Older Italians – Facebook The Truffle Hunters 9 The Most Picturesque Corner of Rome, The Quartiere Coppede 11 Gnocchi alla Romana: The Gnocchi that Aren’t Gnocchi 1 TSDOI Calendar of Events April 12 Interfaith Food Shuttle May ? Movie Night May 15 Bocci Tournament May 16 Helen Wright Dinner June 6 Annual Picnic XXXXX Durham Bulls (Cancelled) Aug 15 Helen Wright Dinner Sep 4 Fund-Raising Breakfast Nov 14 Helen Wright Dinner April Birthdays This month we celebrate the 2021 Scholarships birthdays of those members celebrating in April: Donald TSDOI 2817 is awarding up to two $750 Cimorella (3), Matthew Kunath (4), Pat scholarships. Only direct descendants of TSDOI DiLeonardo (14), Joseph Golaszewski (15), Amy members in good standing are eligible. Winner(s) Stica (18), Joan Kessler (18), Anna Florio (23), must enroll in an accredited college or university in Deborah Nachtrieb (27), Victor Navarroli (28). the fall of 2021. Here is the link to the 2021 application. -

In Memoriam Frederick Dougla

Central Library of Rochester and Monroe County · Historic Monographs Collection Central Library of Rochester and Monroe County · Historic Monographs Collection CANNOT BE PHOTOCOPIED * Not For Circulation Central Library of Rochester and Monroe County · Historic Monographs Collection / III llllllllllll 3 9077 03100227 5 Central Library of Rochester and Monroe County · Historic Monographs Collection jFrebericfc Bouglass t Central Library of Rochester and Monroe County · Historic Monographs Collection fry ^tty <y /z^ {.CJ24. Central Library of Rochester and Monroe County · Historic Monographs Collection Hn flDemoriam Frederick Douglass ;?v r (f) ^m^JjZ^u To live that freedom, truth and life Might never know eclipse To die, with woman's work and words Aglow upon his lips, To face the foes of human kind Through years of wounds and scars, It is enough ; lead on to find Thy place amid the stars." Mary Lowe Dickinson. PHILADELPHIA: JOHN C YORSTON & CO., Publishers J897 Central Library of Rochester and Monroe County · Historic Monographs Collection Copyright. 1897 & CO. JOHN C. YORSTON Central Library of Rochester and Monroe County · Historic Monographs Collection 73 7^ In WLzmtxtrnm 3fr*r**i]Ch anglais; "I have seen dark hours in my life, and I have seen the darkness gradually disappearing, and the light gradually increasing. One by one, I have seen obstacles removed, errors corrected, prejudices softened, proscriptions relinquished, and my people advancing in all the elements I that make up the sum of general welfare. remember that God reigns in eternity, and that, whatever delays, dis appointments and discouragements may come, truth, justice, liberty and humanity will prevail." Extract from address of Mr. -

Public Art Toolkit

Aylesbury Vale Public Art Toolkit Who is this toolkit for? This toolkit can be used by anyone involved with making public art projects happen, however it has been developed to be specifically relevant to people commissioning art within a local authority context. What is public art? Public art has long been a feature of the public spaces across our towns and cities, with sculptures, paintings and murals often recalling historical characters or commemorating important events. Today, public art and artists are increasingly being placed at the centre of regeneration schemes as developers and local authorities recognise the benefits of integrating artworks into such programmes. Public art can include a variety of artistic approaches whereby artists or craftspeople work within the public realm in urban, rural or natural environments. Good public art seeks to integrate the creative skills of artists into the processes that shape the environments we live in. I see what you mean (2008), Lawrence Argent, University of Denver, USA For the Gentle Wind Doth Move Silently, Invisibly, (2006), Brian Tolle, Clevland, USA Spiral, Rick Kirby, (2004), South Woodham Ferres, Essex Animikii - Flies the Thunder, Anne Allardyce, (1992), Thunder Bay, Canada Types of Public Art approaches When thinking about future public art projects it is important to consider the full range of artistic approaches that could be used in a particular site, public art can be permanent or temporary; the following categories summarise popular approaches to public art. Sculpture Sculptural works are not solely about creating a precious piece of art but creating a piece which extends the sculpture into the wider landscape linking it with the environment and focussing attention on what is already there. -

The Ethics of Artistic Appropriation

Taking Charging Bull by the Horns: The Ethics of Artistic Appropriation In the wake of the global stock market crash of 1987, the Sicilian immigrant Arturo Di Modica created the guerilla artwork known as Charging Bull. Without permission, and after spending $350,000 of his own funds, Di Modica had the bull installed in 1989 near Wall Street in New York City during the height of Christmas season to symbolize the strength and power of the American people. Many tourists and locals alike loved the Charging Bull and identified it as “the only significant work of guerrilla capitalist art in existence.” The New York Stock Exchange quickly removed the 3.5-ton statue the day it was installed, but the resulting public outcry led to its “temporary installation” in a nearby location; thirty years later, Charging Bull is still standing strong as one of the most iconic symbols of New York City. On March 7, 2017, Charging Bull was faced with a new opponent. Photo: Anthony Quintano/CC BY 2.0 During the night before International Women’s Day in March 2017, a small sculpture of a young girl was quietly placed in front of Charging Bull. Known as Fearless Girl, the unscheduled installation stands defiantly with her hands on her hips and faces the bull with an unwavering confidence. At the feet of the statue was a bronze plaque that reads “Know the power of women in leadership. SHE makes a difference.” The initial reaction from many people was that this was another act of guerrilla art, one particularly needed now given Wall Street’s challenges with gender equity and diversity. -

Lower Manhattan Public Art Offers Visitors Grand, Open-Air Museum Experience

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Maria Alvarado, (212) 835.2763, [email protected] LOWER MANHATTAN PUBLIC ART OFFERS VISITORS GRAND, OPEN-AIR MUSEUM EXPERIENCE Works by Dubuffet, Koons and Naguchi are among the 14 unique installations featured South of Chambers Street (February 23, 2015) – With more than a dozen masterpieces from world-renowned artists, Lower Manhattan is home to a remarkable and inspiring public art program. The works of art are now featured in a new walking tour itinerary curated by the Downtown Alliance, “Lower Manhattan by Public Art.” The full tour can be found on the Alliance’s website at http://downtownny.com/walkingtours. The walking tour begins at the district’s northernmost edge at 1 Police Plaza, across from City Hall. Here, visitors will find 5-in-1 by Tony Rosenthal. The artist’s work of five interlocking steel discs, rising to a height of 35 feet, represents the five boroughs coming together as one city. Additional pieces of art featured are: Shadows and Flags by Louise Nevelson (William Street between Maiden Lane and Liberty Street) Seven pieces bundled together as a singular abstract unit alludes to the wafting flags, ceremonious spirals, and blooming trees that define the New York City landscape. Group of Four Trees by Jean Dubuffet (28 Liberty Street) The “four trees” are created by a series of intertwined irregular planes, which lean in different directions and are connected by thick black outlines. The piece is part of Dubuffet’s “L’Hourloupe” cycle — a bold, graphic style inspired by a doodle. Sunken Garden by Isamu Noguchi (28 Liberty Street) In the winter, the garden, set one story below ground level, is a dry circular expanse; in the summer, it is transformed into a giant water fountain. -

GREEN PAPER Page 1

AMERICANS FOR THE ARTS PUBLIC ART NETWORK COUNCIL: GREEN PAPER page 1 Why Public Art Matters Cities gain value through public art – cultural, social, and economic value. Public art is a distinguishing part of our public history and our evolving culture. It reflects and reveals our society, adds meaning to our cities and uniqueness to our communities. Public art humanizes the built environment and invigorates public spaces. It provides an intersection between past, present and future, between disciplines, and between ideas. Public art is freely accessible. Cultural Value and Community Identity American cities and towns aspire to be places where people want to live and want to visit. Having a particular community identity, especially in terms of what our towns look like, is becoming even more important in a world where everyplace tends to looks like everyplace else. Places with strong public art expressions break the trend of blandness and sameness, and give communities a stronger sense of place and identity. When we think about memorable places, we think about their icons – consider the St. Louis Arch, the totem poles of Vancouver, the heads at Easter Island. All of these were the work of creative people who captured the spirit and atmosphere of their cultural milieu. Absent public art, we would be absent our human identities. The Artist as Contributor to Cultural Value Public art brings artists and their creative vision into the civic decision making process. In addition the aesthetic benefits of having works of art in public places, artists can make valuable contributions when they are included in the mix of planners, engineers, designers, elected officials, and community stakeholders who are involved in planning public spaces and amenities. -

What Is Public Art?

POLICIES & PROCEDURES MANUAL Updated: February 2015 Contents INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................. 4 What is Public Art? ................................................................................................................................................................................. 4 CITY-FUNDED PUBLIC ART ............................................................................................................... 5 Summary of the Process .......................................................................................................................................................................... 5 Funding Policies ....................................................................................................................................................................................... 6 Funding Procedures ................................................................................................................................................................................. 6 Public Art Manager’s Role ..................................................................................................................................................................... 7 Generating Ideas for Public Art in Capital Projects............................................................................................................................. 8 Methods of Selecting Public Art .......................................................................................................................................................... -

Historic Site Preservation Board

HISTORIC SITE PRESERVATION BOARD DATE: September 18, 2019 PUBLIC HEARING SUBJECT: AN APPLICATION BY TRACY CONRAD AND PAUL MARUT, OWNERS, REQUESTING CLASS 1 HISTORIC RESOURCE DESIGNATION OF 468 WEST TAHQUITZ CANYON WAY, “THE ROLAND BISHOP RESIDENCE”, CASE HSPB #122, APN #513-220-036. (KL). FROM: Department of Planning Services SUMMARY The owners are seeking Class 1 historic resource designation for the Roland P. Bishop Residence located at 468 West Tahquitz Canyon Way. The residence was designed in 1925 in a highly detailed interpretation of the Spanish Colonial Revival style by William J. Dodd of Dodd & Richards Architects. The Bishop Residence was designed and constructed as part of a pair of nearly identical homes which includes the William Meade Residence (aka “The Willows Inn”) located immediately east of the Bishop Residence. Roland P. Bishop was an individual of significance known at an international level as the head of the largest confectionary and baked goods enterprise on the west coast which, in 1930 merged with the National Biscuit Company (now Nabisco). If designated as a Class 1 resource, the property would be subject to the historic preservation requirements of Palm Springs Municipal Code (PSMC) Section 8.05, and present and subsequent owners will be required to maintain the site consistent with that ordinance. In addition, as a Class 1 historic resource, the property owner may apply for a historic property preservation agreement, commonly referred to as a Mills Act Contract. RECOMMENDATION: 1. Open the public hearing and receive public testimony. 2. Close the public hearing and adopt Resolution HSPB 122, “A RESOLUTION OF THE HISTORIC SITE PRESERVATION BOARD OF THE CITY OF PALM SPRINGS, CALIFORNIA, RECOMMENDING THAT THE CITY COUNCIL Historic Site Preservation Board Staff Report: September 10, 2019 HSPB-122 – Roland Bishop Residence Page 2 of 9 DESIGNATE THE PARCEL AT 468 WEST TAHQUITZ CANYON WAY, “THE ROLAND P. -

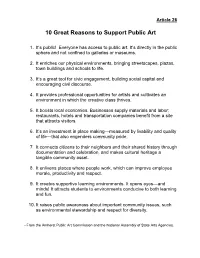

10 Great Reasons to Support Public Art

Article 26 10 Great Reasons to Support Public Art 1. It’s public! Everyone has access to public art. It’s directly in the public sphere and not confined to galleries or museums. 2. It enriches our physical environments, bringing streetscapes, plazas, town buildings and schools to life. 3. It’s a great tool for civic engagement, building social capital and encouraging civil discourse. 4. It provides professional opportunities for artists and cultivates an environment in which the creative class thrives. 5. It boosts local economies. Businesses supply materials and labor; restaurants, hotels and transportation companies benefit from a site that attracts visitors. 6. It’s an investment in place making—measured by livability and quality of life—that also engenders community pride. 7. It connects citizens to their neighbors and their shared history through documentation and celebration, and makes cultural heritage a tangible community asset. 8. It enlivens places where people work, which can improve employee morale, productivity and respect. 9. It creates supportive learning environments. It opens eyes—and minds! It attracts students to environments conducive to both learning and fun. 10. It raises public awareness about important community issues, such as environmental stewardship and respect for diversity. --From the Amherst Public Art Commission and the National Assembly of State Arts Agencies. The Amherst Public Art Commission Why Public Art for Amherst? Public art adds enormous value to the cultural, aesthetic and economic vitality of a community. It is now a well-accepted principle of urban design that public art contributes to a community’s identity, fosters community pride and a sense of belonging, and enhances the quality of life for its residents and visitors.