Encumbered by Stage Fright Or I'm Not Sure Why I Did That

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs No. Interpret Title Year of release 1. Bob Dylan Like a Rolling Stone 1961 2. The Rolling Stones Satisfaction 1965 3. John Lennon Imagine 1971 4. Marvin Gaye What’s Going on 1971 5. Aretha Franklin Respect 1967 6. The Beach Boys Good Vibrations 1966 7. Chuck Berry Johnny B. Goode 1958 8. The Beatles Hey Jude 1968 9. Nirvana Smells Like Teen Spirit 1991 10. Ray Charles What'd I Say (part 1&2) 1959 11. The Who My Generation 1965 12. Sam Cooke A Change is Gonna Come 1964 13. The Beatles Yesterday 1965 14. Bob Dylan Blowin' in the Wind 1963 15. The Clash London Calling 1980 16. The Beatles I Want zo Hold Your Hand 1963 17. Jimmy Hendrix Purple Haze 1967 18. Chuck Berry Maybellene 1955 19. Elvis Presley Hound Dog 1956 20. The Beatles Let It Be 1970 21. Bruce Springsteen Born to Run 1975 22. The Ronettes Be My Baby 1963 23. The Beatles In my Life 1965 24. The Impressions People Get Ready 1965 25. The Beach Boys God Only Knows 1966 26. The Beatles A day in a life 1967 27. Derek and the Dominos Layla 1970 28. Otis Redding Sitting on the Dock of the Bay 1968 29. The Beatles Help 1965 30. Johnny Cash I Walk the Line 1956 31. Led Zeppelin Stairway to Heaven 1971 32. The Rolling Stones Sympathy for the Devil 1968 33. Tina Turner River Deep - Mountain High 1966 34. The Righteous Brothers You've Lost that Lovin' Feelin' 1964 35. -

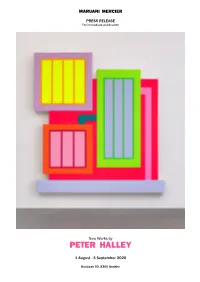

Peter Halley 2020

MARUANI MERCIER PRESS RELEASE For immediate publication New Works by PETER HALLEY 1 August - 3 September 2020 Kustlaan 90, 8300 Knokke MARUANI MERCIER is proud to announce their 9th exhibition with the American Neo-Conceptualist artist Peter Halley at their gallery in Knokke from 1 to 31 August 2020. Peter Halley was born in New York City in 1953. He received his BA from Yale University and his MFA from the University of New Orleans in 1978. Moving to New York City had big influence on Halley’s painting style. Its three-dimensional urban grid led to geometric paintings that engage in a play of relationships between so-called "prisons" and "cells" – icons that reflect the increasing geometricization of social space in the world. Halley began to use colors and materials with specific connotations, such as fluorescent Day-Glo paint, mimcking the eerie glow artificial lighting and reflective clothing and signs, as well as Roll-a-Tex, a texture additive used as surfacing in suburban buildings. Halley is part of the generation of Neo-Conceptualist artists that first exhibited in New York’s East Village, including Jeff Koons, Haim Steinbach, Mayier Vaisman and Ashley Bickerton. These artists became identified on a wider scale with the labels Neo-Geo and Neo-Conceptualism, an art practice deriving from the conceptual art movement of the 1960s and 1970s. Focussing on the commodification of art and its relation to gender, race, and class, neo-conceptualists question art and art institutions with irony and pastiche. Halley's works were included in the Sao Paolo Biennale, the Whitney Biennale and the 54th Venice Biennale and represented in such museums and art institutions as the CAPC Musee d'Art Contemporain, Bordeaux; the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia, Madrid; the Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam; the Des Moines Art Center; The Tate Modern, London; the Dallas Museum of Art; the Museum of Modern Art, New York; the Kitakyushu Municipal Museum of Art; the Museum Folkwang, Essen and the Butler Institute of American Art. -

Form: Set List Select Several Songs to Be Played at Your Event / Party

FORM: SET LIST SELECT SEVERAL SONGS TO BE PLAYED AT YOUR EVENT / PARTY SONGS YOU CAN EAT AND DRINK TO MEDLEYS SONGS YOU CAN DANCE TO Earth, Wind & Fire - Can't Hide Love LCD Soundsystem – I Can Change Shuggie Otis - Strawberry Letter 23 Earth, Wind & Fire - Let’s Groove LFT - Quadron Simple Minds - Don't You Forget About Me Beach Boys - God Only Knows Daft Punk Medley Adele - Rolling in the Deep Earth, Wind & Fire - September Little Richard - Good Golly Miss Molly Spice Girls - Say You'll Be There Belle and Sebastian - Your Covers Blown 90's R&B Medley Al Green - Love and Happiness Earth, Wind & Fire - Sing a Song Looking Glass - Brandy St. Vincent - Digital Witness Black Keys - Gold On the Ceiling TLC Amy Winehouse - Valerie ELO - Don’t Bring Me Down Loudon Wainwright - Daughter Stealers Wheel - Stuck in the Middle With You Bon Iver – Holocene Usher Ariel Pink - Round + Round ELO - Mr. Blue Sky Lou Reed – Walk on the Wild Side Steely Dan - Hey Nineteen Bon Iver - Re: Stacks Montell Jordan Beach Boys - Don’t Worry Baby Elton John - Tiny Dancer Lykke Li - I follow Rivers Steely Dan - Peg Bon Iver - Skinny Love Mark Morrison Beach Boys - God Only Knows Empire of the Sun - Walking On a Dream Madonna - Like A Prayer Stevie Nicks - Leather & Lace Christopher Cross - Sailing Next Beach Boys - Wouldn’t It Nice Eric Clapton - Wonderful Tonight Madonna - Lucky Star Stevie Nicks - Stand Back David Bowie - Ziggy Stardust 80's Pop + New Wave Medley Beck - Debra Father John Misty - Chateau Lobby #4 Major Lazer – Lean On Stevie Wonder - Higher Ground Eagles - Hotel California New Order Beck - Where It’s At Feist - 1,2,3,4 Mariah Carey - Always Be My Baby Stevie Wonder - I Believe (When I Fall In Love) ELO - Mr. -

PDF (V. 86:21, March 15, 1985)

COV\q(~UI~6)\SJ CCfl..'\~ THE ro.:h!\lrl-r0\1\S I K~r-lo.\. CALIFORNIA ::red \. VOLUME 86 PASADENA, CALIFORNIA / FRIDAY 15 MARCH 1985 NUMBER ~1 Admiral Gayler Speaks On The Way Out by Diana Foss destroyed just as easily by a gravi- Last Thursday, the Caltech ty bomb dropped from a plane as Distinguished Speakers Fund, the by a MIRVed ICBM. In fact, Caltech Y, and the Caltech World technology often has a highly Affairs Forum jointly sponsored a detrimental effect. Improved ac talk by Admiral Noel Gayler entitl- curacy of nuclear missles has led ed, "The Way Out: A General to the ability to target silos with Nuclear Settlement." The talk, pinpoint precision. This leads to the which was given in Baxter Lecture dangerous philosophy of "use Hall, drew about sixty people, them or lose them," with such mainly staff, faculty, and graduate manifestations as preemptive students, with a sprinkling of strikes and launch-on-warning undergraduates. President systems. Goldberger introduced Admiral While Gayler views as laudable 15' Gayler, who is a former Com- Reagan's attempts to find a more :tl mander in Chiefofthe Pacific Fleet "humane" policy than Mutually ~ and a former director of the Na- Assured Detruction, he sees the ~ tional Security Agency. Space Defense Initiative as a .s Gayler began his talk by em- fruitless attempt to use technology ~ phasizing the. threat of the huge to work impossible miracles, part -a nuclear stockpiles of the two super- of a general trend to make science I powers. The numbers themselves, an omnipotent god. -

Personal Structures Culture.Mind.Becoming La Biennale Di Venezia 2013

PERSONAL STRUCTURES CULTURE.MIND.BECOMING LA BIENNALE DI VENEZIA 2013 PALAZZO BEMBO . PALAZZO MORA . PALAZZO MARCELLO ColoPHON CONTENTS © 2013. Texts by the authors PERSONAL STRUCTURES 7 LAURA GURTON 94 DMITRY SHORIN 190 XU BINg 274 © If not otherwise mentioned, photos by Global Art Affairs Foundation PATRICK HAMILTON 96 NITIN SHROFF 192 YANG CHIHUNg 278 PERSONAL STRUCTURES: ANNE HERZBLUTh 98 SUH JEONG MIN 194 YE YONGQINg 282 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored THE ARTIsts 15 PER HESS 100 THE ICELANDIC YING TIANQI 284 in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, CHUL HYUN AHN 16 HIROFUMI ISOYA 104 LOVE CORPORATION 196 ZHANG FANGBAI 288 electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without YOSHITAKA AMANO 20 SAM JINKS 106 MONIKA THIELE 198 ZHANG GUOLONg 290 permission of the editor. ALICE ANDERSON 22 GRZEGORZ KLATKA 110 MICHELE TOMBOLINI 200 ZHANG HUAN 292 Jan-ERIK ANDERSSON 24 MEHdi-GeorGES LAHLOU 112 ŠtefAN TÓTh 202 ZHENG CHONGBIN 294 Print: Krüger Druck + Verlag, Germany AxEL ANKLAM 26 JAMES LAVADOUR 114 VALIE EXPORT 204 ZHOU CHUNYA 298 ATELIER MORALES 28 Edited by: Global Art Affairs Foundation HELMUT LEMKE 116 VITALY & ELENA VASIELIEV 208 INGRANDIMENTO 301 YIFAT BEZALEl 30 www.globalartaffairs.org ANNA LENZ 118 BEN VAUTIER 212 CHAILE TRAVEL 304 DJAWID BOROWER 34 LUCE 120 RAPHAEL VELLA 218 FAN ANGEl 308 FAIZA BUTT 38 Published by: Global Art Affairs Foundation ANDRÉ WAGNER 220 GENG YINI 310 GENIA CHEF 42 MICHELE MANZINI 122 in cooperation with Global Art Center -

WS Folk Riot Booklet

1 playing “cover” songs as diverse and influential Meanwhile, due to our leftist leanings and omni- 10,000 Watts of Folk as the Statler Brothers’ “Flowers on the Wall,” presence in the Village, activist Abbie Hoffman 1. I AIN’T KISSING YOU (0:54) by Trixie A. Balm met with we three Squares and co-wrote a theme VANGUARD STUDIOS, NYC (aka Lauren Agnelli) Alas, that deal fell through. though the song for his new live radio show, “Radio Free September 1985 sessions remain, with Tom, Lauren, Bruce and Billy U.S.A.”: heard here for the first time since the playing “cover” songs as diverse and influential debut show back in 1986 at the Village Gate. By 1985, we Washington Squares, having worked, as the Statler Brothers’ “Flowers on the Wall,” Vanguard, an important folk label during the ‘50s sang and played our way through the ‘80’s Richard Hell’s “Love Comes in Spurts,” Lou Reed’s At last, in 1987, Gold Castle/Polydor records who and ‘60s was sold in 1985. Vanguard sold off their Greenwich Village folk scene fray, were ready to “Sweet Jane,” and Johnny Thunders’ “Chinese Rocks.” DID sign us to a deal found the perfect sound classical collection and reissued their folk and then record. The record company interest was there though producer Mitch Easter (of the group Let’s started looking for new acts. With a bunch of well and soon serious recording contracts would dangle Having somewhat mastered those formative nuggets, Active— he also recorded REM’s initial sessions) known original Vanguard producers in the control room: before our fresh (very fresh!) young smirks. -

LONG ISLAND WEEKLY Lpublished by Anton Mediai Group • Mwarch 23 - 29, 2016 Vol

1 LONG ISLAND WEEKLY LPublished by Anton MediaI Group • MWarch 23 - 29, 2016 Vol. 3, No. 11 $1.00 LongIslandWeekly.com EXCLUSIVE SouthernAmericana bard Lucinda Gothic Williams SEE OUR 2016 SPRING CAMPAIGN INSIDE ON THE BACK COVER. BROADWAY’S LOVE AFFAIR WITH PARIS GERMAN FOOD IS WUNDERBAR AT PLATTDUETSCHE SPECIAL SECTION: BANKING & FINANCE YEARS 4A ANTON MEDIA GROUP • MARCH 23 - 29, 2016 Visiting The Ghosts Of Highway 20 Lucinda Williams takes a musical trip into her past Lucinda Williams (Photo by David McClister) BY DAVE GIL DE RUBIO vocation as a visiting college professor— project. It’s particularly effective on music. It’s an exercise she did on the last [email protected] places like Vicksburg, MS, and Minden, character-driven fare like the sleepy record via the gorgeous acoustic opener LA—Williams has recorded 14 songs jazz arrangement that tells the tale of a “Compassion.” As she admits, transpos- In the 1968 song, “Salt of the Earth,” populated by the same kinds of blue junkie in “I Know All About It” and the ing from a poem to a song is an inexact the Rolling Stones once sang, “Let’s collar individuals she came to know bluesy “Doors of Heaven,” which finds science she’s getting the hang of. drink to the hard working people/ growing up in the Deep South. Williams taking on the world-weary “That’s the thing, when you’re Let’s think of the lowly of birth/Spare a The Louisiana native and her long- voice of a dying person ready to singing, the words kind of have to roll thought for the rag taggy people/Let’s time rhythm section of David Sutton move on. -

Peter Halley

PETER HALLEY BIOGRAPHY 1953 Born in New York City 1971 Graduates from Phillips Academy, Andover, Massachusetts 1975 Studies at Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut 1976 Moves to New Orleans 1978 Studies at University of New Orleans 1980 Moves to New York City 1981 Publishes ‘Beat, Minimalism, New Wave, and Robert Smithson’, the first of six essays to appear in Arts Magazine, New York 1985 Solo exhibition at International with Monument, New York 1989 Solo exhibition at the Museum Haus Esters, Krefeld, Germany 1991 Retrospective at CAPC Musée d’art contemporain, Bordeaux. Exhibition tours to FAE Musée d’art contemporain, Pully/Lausanne, the Reina Sofía, Madrid, and the Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam 1995 First large-scale installation at the Dallas Museum of Art 1996 Founds index, a bi-monthly magazine covering independent culture. Publishes index until 2005 1996-99 Serves as Adjunct Professor, U.C.L.A., School of Art and Architecture, Los Angeles 1997 New Concepts of Printmaking 1: Peter Halley at the Museum of Modern Art, New York 1999 Appointed Senior Lecturer in Painting, Yale University, School of Art, New Haven, Connecticut 2000 Begins teaching as Adjunct Professor, Columbia University, New York City 2001 Receives the annual Frank Jewett Mather Award for published art criticism from the College Art Association 2002 Appointed Director of Graduate Studies in Painting and Printmaking at the Yale University School of Art, until 2011 Permanent installation of wall-size digital prints at the public library in Usera, Spain, commissioned -

Peter Halley Paintings of the 1980S the Catalogue Raisonné Cara Jordan Table of Contents

Peter Halley Paintings of the 1980s The Catalogue Raisonné Cara Jordan Table of Contents Introduction 4 Cara Jordan Facts Are Useless in Emergencies 6 Paul Pieroni Guide to the Catalogue Raisonné 11 Catalogue Raisonné Peter Halley in front of his first New York studio at 128 East 7th Street, 1985 1980 13 1981 23 1982 37 1983 47 1984 59 1985 67 1986 93 1987 125 1988 147 1989 167 Appendix Biography 187 Solo Exhibitions 1980–1989 188 Group Exhibitions 1980–1989 190 Introduction Cara Jordan The publication of this catalogue raisonné of Peter Halley’s through a diagrammatic representation of space. His paintings French Post-Structuralist theorists such as Michel Foucault and and SCHAUWERK Sindelfingen; and the numerous galleries paintings from the 1980s offers a significant opportunity to reflect transformed the paradigmatic square of abstract art into refer- Jean Baudrillard to the North American art world—emphatically and art dealers who have supported Halley’s work throughout on the early works and career of one of the most well-known en tial icons that he labeled “prisons” and “cells,” and linked them refuted the traditional humanist and spiritual aspirations of art.1 the years, including Thomas Ammann Fine Art AG, Galerie artists of the Neo-Conceptualist generation. It was during these by means of straight lines he called “conduits.” Through this His writings described the shifting relationship between the Bruno Bischofberger, Galerie Andrea Caratsch, Greene Naftali years that Halley developed the hallmark iconography and formal simple icono graphy, which remains the basis of Halley’s visual individual and larger social structures triggered by technology Gallery, Margo Leavin Gallery, Galería Javier López & Fer language of his paintings, which connected the tradition of language, he created a compartmentalized space connected by and the digital revolution, leading critic Paul Taylor to name Francés, Maruani Mercier Gallery, and Sonnabend Gallery. -

Research on the Characteristics of Abstract Painting

2020 8th International Education, Economics, Social Science, Arts, Sports and Management Engineering Conference (IEESASM 2020) Research on the Characteristics of Abstract Painting Luomin Pan Graduate School of Namseoul University, Cheonan 31020, Korea [email protected] Keywords: Abstract painting, Light and color, Music, Space Abstract: This article analyzes the painting works of the representative artists of the AbstractSchool and the New AbstractSchool, and conducts an Expandability research on the characteristics of Abstractpainting. The first part, “The Confusion of Light and Color”, is to understand the color of “multi-personality” from a new perspective. Color does not have immutable meanings forever. The signs of color depend on the artist's creative intentions. The second part, “The Musical Sense of AbstractPainting”, analyzes the musicality of painting through points, lines and surfaces. The musicality of painting allows us to think about more possibilities in the parallel world of painting and music. The third part “Reconstruction of Space” analyzes the multi-dimensional space of Abstractpainting, the indifferent two-dimensional space between two-dimensional and three-dimensional, the multi-dimensional space in two-dimensional and the new space. The study of painting space is an important proposition of Abstractpainting. The author hopes to explore the characteristics of Abstractpainting to inspire us how to deal with old things and old topics, to make new thinking, and to provide more templates for artistic creation and thinking on easel. 1. Introduction The light and color in painting is a basic concept. Only when there is light, there is color. The color we are discussing here refers to the color of painting, and light is the premise of its appearance. -

“9” Just Short of a Perfect 10

6 AQUINAS THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 17, 2009 7 Arts & Life Editor Joe Wolfe Brand New’s darker “Daisy” VMAs still full Campus Comment COMMentarY BY Arts Life Nicholas Chinman Dervela O’BRIEN of surprises & Staff Writer In the aftermath of the West Fans of the alternative-rock COMMentarY BY incident, Swift stunned the audi- band, Brand New, are anxiously TIM SIMpsON ence with her live performance. Download awaiting the release of the band’s Staff Writer She sang her award winning “9” just short of a perfect 10 fourth album entitled “Daisy,” single “You Belong with Me” in a which is scheduled to be released On September 13, the 2009 crowded New York City subway of the September 22. After almost three MTV Video Music Awards took COMMentarY BY with fans providing the back- years of touring and writing new place at Radio City Music Hall ground vocals to her tune. She JEREMY Evans material since their well-received in New York City. For the sec- week glowed with enthusiasm while Staff Writer “The Devil and God Are Raging ond consecutive year, the event spinning around in circles, danc- Inside Me,” the Long Island native was hosted by comedian Russell ing on the seats and involving In 2005, Shane Acker created band has worked hard to put to- Brand. several members of the crowd an animated short as a student “Pale Blue gether their latest album, which is The night began with a heart- in her upbeat performance. Af- project. He crafted a fascinating sure to surprise its listeners. felt speech delivered by Madon- ter leaving the subway, she and world, one which caught the at- “Daisy” follows many of the na in honor of her late friend Mi- PHOTO BY BRAND NEW MYSPACE PAGE her fans ran to the front of Radio tention of many in the film-mak- Eyes” same dark philosophical themes chael Jackson. -

The Velvet Underground By: Kao-Ying Chen Shengsheng Xu Makenna Borg Sundeep Dhanju Sarah Lindholm Group Introduction

The Velvet Underground By: Kao-Ying Chen Shengsheng Xu Makenna Borg Sundeep Dhanju Sarah Lindholm Group Introduction The Velvet Underground helped create one of the first proto-punk songs and paved the path for future songs alike. Our group chose this group because it is one of those groups many people do not pay attention to very often and they are very unique and should be one that people should learn about. Shengsheng Biography The Velvet Underground was an American rock band formed in New York City in 1964. They are also known as The Warlocks and The Falling Spikes. Best-known members: Lou Reed and John Cale. 1967 debut album, “The Velvet Underground & Nico” was named the 13th Greatest Album of All Time, and the “most prophetic rock album ever http://t2.gstatic.com/images?q=tbn:ANd9GcTpZBIJzRM1H- made” by Rolling Stone in 2003. GhQN6gcpQ10MWXGlqkK03oo543ZbNUefuLNAvVRA Ranked #19 on the “100 Greatest Artists of All Time” by Rolling Stone. Shengsheng Biography From 1964-1965: Lou Reed (worked as a songwriter) met John Cale (Welshman who came to United States to study classical music) and they formed, The Primitives. Reed and Cale recruited Sterling Morrison to play the guitar (college classmate of Reed’s) as a replacement for Walter De Maria. Angus MacLise joined as a percussionist to form a group of four. And this quartet was first named The Warlocks, then The Falling Spikes. Introduced by Michael Leigh, the name “The Velvet Underground” was finally adopted by the group in Nov 1965. Shengsheng Biography From 1965-1966: Andy Warhol became the group’s manager.