Curating and Annotating a Collection of Traditional Irish flute Recordings to Facilitate Stylistic Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Chieftains 3 Album Download MQS Albums Download

the chieftains 3 album download MQS Albums Download. Mastering Quality Sound,Hi-Res Audio Download, 高解析音樂, 高音質の音楽. Van Morrison & The Chieftains – Irish Heartbeat (Remastered) (1988/2020) [FLAC 24bit/96kHz] Van Morrison & The Chieftains – Irish Heartbeat (Remastered) (1988/2020) FLAC (tracks) 24-bit/96 kHz | Time – 38:56 minutes | 815 MB | Genre: Rock Studio Master, Official Digital Download | Front Cover | © Legacy Recordings. “Irish Heartbeat”, a collaboration album with Van Morrison, was Van’s first attempt to reconcile his Celtic roots with his blues and soul music. It was also The Chieftains’ first full blown collaboration album. Although there were worries about working with a major rock star, the recording was a success, introducing elements of Van’s unique soul and jazz style singing to traditional songs and music. This was the beginning of an ongoing successful musical relationship between Van and The Chieftains. “Irish Heartbeat” was nominated for a Grammy Award in 1989, and there followed a tour of Europe and the UK. “On their wide musical journeys in the ’80s, the Chieftains decided to collaborate with Van Morrison, who had an artistic peak at the end of the decade. The result was a highlight in both of their ’80s productions: the traditional Irish Heartbeat, with Morrison on lead vocals and a guest appearance from the Mary Black. Morrisonand Moloney’s production puts the vocals up front with a sparse background, sometimes with a backdrop of intertwining strings and flutes, the same way Morrison would later use the Chieftains on his Hymns to the Silence. The arrangement and the artist’s engaged singing leads to a brilliant result, and these Irish classics are made very accessible without being transformed into pop songs. -

The Chieftains Boil the Breakfast Early Mp3, Flac, Wma

The Chieftains Boil The Breakfast Early mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Folk, World, & Country Album: Boil The Breakfast Early Country: US Style: Folk, Celtic MP3 version RAR size: 1255 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1271 mb WMA version RAR size: 1718 mb Rating: 4.2 Votes: 401 Other Formats: MP2 AHX DXD TTA MP1 APE VOX Tracklist 1 Boil The Breakfast Early 3:56 2 Mrs. Judge 3:43 3 March From Oscar And Malvina 4:16 4 When A Man's In Love 3:40 5 Bealach An Doirín 3:46 6 Ag Taisteal Na Blárnan 3:21 7 Carolan's Welcome 2:53 8 Up Against The Buachalawns 4:04 9 Gol Na Mban San Ár 4:20 Chase Around The Windmil (Medley) (5:01) 10.a Toss The Feathers 10.b Ballinasloe Fair 10.c Cailleach an Airgid 10.d Cuil Aodha Slide 10.e The Pretty Girl Companies, etc. Copyright (c) – CBS Records Inc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – Claddagh Records Ltd. Manufactured By – Columbia Records Recorded At – Windmill Lane Studios Mixed At – Windmill Lane Studios Credits Bagpipes [Uilleann Pipes], Tin Whistle – Paddy Moloney Bodhrán, Vocals – Kevin Conneff Cello – Jolyon Jackson Drums – The Rathcoole Pipe Band Drum Corps* Engineer – Brian Masterson Fiddle – Seán Keane* Fiddle, Bones – Martin Fay Flute, Tin Whistle – Matt Molloy Harp [Neo Irish Harp, Mediaval Harp], Dulcimer [Tiompan] – Derek Bell Liner Notes – Ciarán Mac Mathúna Producer – Paddy Moloney Notes Originally recorded in 1979. Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode: 0 7464 36401 2 Other (DADC Code): DIPD 071877 Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Boil The Breakfast -

Rhythm Bones Player a Newsletter of the Rhythm Bones Society Volume 10, No

Rhythm Bones Player A Newsletter of the Rhythm Bones Society Volume 10, No. 3 2008 In this Issue The Chieftains Executive Director’s Column and Rhythm As Bones Fest XII approaches we are again to live and thrive in our modern world. It's a Bones faced with the glorious possibilities of a new chance too, for rhythm bone players in the central National Tradi- Bones Fest in a new location. In the thriving part of our country to experience the camaraderie tional Country metropolis of St. Louis, in the ‗Show Me‘ state of brother and sisterhood we have all come to Music Festival of Missouri, Bones Fest XII promises to be a expect of Bones Fests. Rhythm Bones great celebration of our nation's history, with But it also represents a bit of a gamble. We're Update the bones firmly in the center of attention. We betting that we can step outside the comfort zones have an opportunity like no other, to ride the where we have held bones fests in the past, into a Dennis Riedesel great Mississippi in a River Boat, and play the completely new area and environment, and you Reports on bones under the spectacular arch of St. Louis. the membership will respond with the fervor we NTCMA But this bones Fest represents more than just have come to know from Bones Fests. We're bet- another great party, with lots of bones playing ting that the rhythm bone players who live out in History of Bones opportunity, it's a chance for us bone players to Missouri, Kansas, Illinois, Oklahoma, and Ne- in the US, Part 4 relive a part of our own history, and show the braska will be as excited about our foray into their people of Missouri that rhythm bones continue (Continued on page 2) Russ Myers’ Me- morial Update Norris Frazier Bones and the Chieftains: a Musical Partnership Obituary What must surely be the most recognizable Paddy Maloney. -

Irish Bands of the 60S & 70S | Sample Answer

Irish Bands of the 60s & 70s | Sample answer Ceoltóiri Cualann was an Irish group formed by Sean O’Riada in 1961. O’Riada had the idea of forming Ceoltóiri Cualann following the success of a group he had put together to perform music for the play “The Song of the Anvil” in 1960. Ceoltóiri Cualann would be a group to play Irish traditional songs with accompaniment and traditional dance tunes and slow airs. All folk music recorded before that time had been highly orchestrated and done in a classical way. Another aim of O’Riada’s was to revitalise the work of harpist and composer Turlough O’Carolan. Ceoltóiri Cualann was launched during a festival in Dublin in 1960 at an event called Recaireacht an Riadaigh and was an immediate success in Dublin. The group mainly played the music of O’Carolan, sean nós style songs and Irish traditional tunes, and O’Riada introduced the bodhrán as a percussion instrument. Ceoltóiri Cualann had ceased playing with any regularity by 1969 but reunited to record “O’Riada” and “O’Riada Sa Gaiety” that year. “O’Riada Sa Gaiety” was not released until after O’Riada’s death in 1971. The members of Ceoltóiri Cualann, some of whom went on to form “The Chieftains” in 1963 were O’Riada (harpsichord and bodhrán), Martin Fay, John Kelly (both fiddle), Paddy Moloney (uilleann pipes), Michael Turbidy (flute), Sonny Brogan, Éamon de Buitléir (both accordian), Ronnie Mc Shane (bones), Peadar Mercer (bodhrán), Seán Ó Sé (tenor voice) and Darach Ó Cathain (sean nós singer. Some examples of their tunes are “O’ Carolan’s Concerto” and “Planxty Irwin”. -

Of ABBA 1 ABBA 1

Music the best of ABBA 1 ABBA 1. Waterloo (2:45) 7. Knowing Me, Knowing You (4:04) 2. S.O.S. (3:24) 8. The Name Of The Game (4:01) 3. I Do, I Do, I Do, I Do, I Do (3:17) 9. Take A Chance On Me (4:06) 4. Mamma Mia (3:34) 10. Chiquitita (5:29) 5. Fernando (4:15) 11. The Winner Takes It All (4:54) 6. Dancing Queen (3:53) Ad Vielle Que Pourra 2 Ad Vielle Que Pourra 1. Schottische du Stoc… (4:22) 7. Suite de Gavottes E… (4:38) 13. La Malfaissante (4:29) 2. Malloz ar Barz Koz … (3:12) 8. Bourrée Dans le Jar… (5:38) 3. Chupad Melen / Ha… (3:16) 9. Polkas Ratées (3:14) 4. L'Agacante / Valse … (5:03) 10. Valse des Coquelic… (1:44) 5. La Pucelle d'Ussel (2:42) 11. Fillettes des Campa… (2:37) 6. Les Filles de France (5:58) 12. An Dro Pitaouer / A… (5:22) Saint Hubert 3 The Agnostic Mountain Gospel Choir 1. Saint Hubert (2:39) 7. They Can Make It Rain Bombs (4:36) 2. Cool Drink Of Water (4:59) 8. Heart’s Not In It (4:09) 3. Motherless Child (2:56) 9. One Sin (2:25) 4. Don’t We All (3:54) 10. Fourteen Faces (2:45) 5. Stop And Listen (3:28) 11. Rolling Home (3:13) 6. Neighbourhood Butcher (3:22) Onze Danses Pour Combattre La Migraine. 4 Aksak Maboul 1. Mecredi Matin (0:22) 7. -

CA Activities Update - January 18, 2014

CA Activities Update - January 18, 2014 Lifestyle Department January 18, 2014 Click here to access the CA Activities Calendar Onsite • The Studebakers, January 22, 6 - 8 p.m., SCB, $11 • Red Alert – Rock N Roll Dance, January 24, 7 - 10 p.m., $11 pp • Mars Curiosity: Amazing Mission, January 28, 1 p.m., SCB, $5 pp Outings • 3 Laps in a Lamborghini, February 21, $172 pp • "Spurs Nation" Basketball, February 26, $100 pp • Celtic Music - The Chieftains at The Riverbend Centre, February 26, $92 pp • The Olympics of the Violin & Dinner at BRIO, Saturday, March 1, $110 pp Extended Travel • The Gardens of London • New York City • Canadian Rockies by Train • Royal Caribbean Alaska Cruise Tour • Scenic Switzerland by Train • Trains of the Colorado Rockies • Colorado Springs Getaway • Fall Foliage Cruise Onsite The Studebakers – Performance Wednesday, January 22, 6 - 8 p.m., SCB, $11 Open Seating Cabaret Style Harmonizing since 1993, The Studebakers are influenced by The Andrews Sisters, The Boswell Sister, The Chenille Sister, Glenn Miller, Tommy Dorsey and The Manhattan Transfer. Jill Montgomery started the group, wanting to bring back the marvelous melodies and lyrics of the songs from the ’20s, ’30s and ’40s and deliver them with the clarity and close harmony that made them such big favorites. The band consists of five members: Jill Montgomery, Becky Cavanaugh and Sharon Maner are the core trio, singing tunes made famous by the Andrews Sisters and Boswell Sisters among others; Randy Seybold plays virtuoso bass and guitar and sings baritone; and Marilyn Rucker joins in on keyboards and vocals. -

Concert & Dance Listings • Cd Reviews • Free Events

CONCERT & DANCE LISTINGS • CD REVIEWS • FREE EVENTS FREE BI-MONTHLY Volume 4 Number 6 Nov-Dec 2004 THESOURCE FOR FOLK/TRADITIONAL MUSIC, DANCE, STORYTELLING & OTHER RELATED FOLK ARTS IN THE GREATER LOS ANGELES AREA “Don’t you know that Folk Music is illegal in Los Angeles?” — WARREN C ASEY of the Wicked Tinkers Music and Poetry Quench the Thirst of Our Soul FESTIVAL IN THE DESERT BY ENRICO DEL ZOTTO usic and poetry rarely cross paths with war. For desert dwellers, poetry has long been another way of making war, just as their sword dances are a choreographic represen- M tation of real conflict. Just as the mastery of insideinside thisthis issue:issue: space and territory has always depended on the control of wells and water resources, words have been constantly fed and nourished with metaphors SomeThe Thoughts Cradle onof and elegies. It’s as if life in this desolate immensity forces you to quench two thirsts rather than one; that of the body and that KoreanCante Folk Flamenco Music of the soul. The Annual Festival in the Desert quenches our thirst of the spirit…Francis Dordor The Los Angeles The annual Festival in the Desert has been held on the edge Put On Your of the Sahara in Mali since January 2001. Based on the tradi- tional gatherings of the Touareg (or Tuareg) people of Mali, KlezmerDancing SceneShoes this 3-day event brings together participants from not only the Tuareg tradition, but from throughout Africa and the world. Past performers have included Habib Koité, Manu Chao, Robert Plant, Ali Farka Toure, and Blackfire, a Navajo band PLUS:PLUS: from Arizona. -

Port Na Bpúcaí Title Code 1 Altan 25Th Anniversary Celebration with The

Port na bPúcaí Title Code Aberlour's Save the last drop 9,95 1 Abbey Ceili Band Bruach at StSuiain 9,95 1 Afro Celt Sound System POD (CD & DVD) CDRW 116 18,95 Afro Celt Sound System Vol 1 - Sound Magic CDRW61 14,95 Afro Celt Sound System Vol 2 - Release CDRW76 14,95 1 Afro Celt Sound System Vol 3 - Further in time CDRW96 14,95 Afro Celt Sound System Anatomic CDRW133 16,95 Afro Celt Sound System Seed CDRWG111 Altan 25th Anniversary Celebration with the ALT001 16,95 2 RTE concert orchestra Altan Altan ( Frankie & Mairead ) GLCD 1078 16,95 Altan another sky... 724384883829 12,95 Altan Best of, The (2CDs) GLCD 1177 16,95 1 Altan The best of Altan - The Songs 7, 24354E+11 9,95 Altan Blackwater CDV2796 12,95 Altan Blue Idol, The CDVE961/ 8119552 16,95 Altan Finest, The CCCD100 8,95 Altan First ten years 1986-1995, The GLCD 1153 14,95 Altan Glen Nimhe - The Poison Glen COM4571 16,95 Altan harvest storm GLCD 1117 16,95 Altan horse with a heart GLCD 1095 16,95 Altan island angel GLCD 1137 16,95 1 Altan Local ground VERTCD069 19,95 Altan Runaway sunday CDV2836 12,95 Altan Red crow, The GLCD 1109 16,95 Altan The widening gyre 16,95 1 Ancient voice of Ireland Haunting Irish melodies 9,95 2 Anúna Anúna DANU21 9,95 1 Anúna Deep dead blue DANU020 14,95 Anúna Illumination DANU029 Anúna Invocation DANU015 14,95 Anúna Sanctus DANU025 14,95 Anúna Winter Songs DANU 16 14,95 Arcade Fire The subburbs 6,95 5 Arcady After the ball.. -

The Chieftains

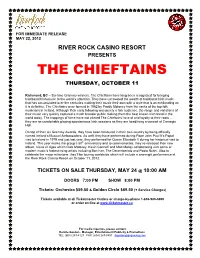

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE MAY 22, 2012 RIVER ROCK CASINO RESORT PRESENTS THE CHIEFTAINS THURSDAY, OCTOBER 11 Richmond, BC – Six-time Grammy winners, The Chieftains have long been recognized for bringing traditional Irish music to the world’s attention. They have uncovered the wealth of traditional Irish music that has accumulated over the centuries making their music their own with a style that is as exhilarating as it is definitive. The Chieftains were formed in 1962 by Paddy Moloney from the ranks of the top folk musicians in Ireland. Although their early following was purely a folk audience, the range and variations of their music very quickly captured a much broader public making them the best known Irish band in the world today. The trappings of fame have not altered The Chieftains’ love of and loyalty to their roots … they are as comfortable playing spontaneous Irish sessions as they are headlining a concert at Carnegie Hall. On top of their six Grammy Awards, they have been honoured in their own country by being officially named Ireland’s Musical Ambassadors. As well, they have performed during Pope John Paul II’s Papal visit to Ireland in 1979 and just last year, they performed for Queen Elizabeth II during her historical visit to Ireland. This year marks the group’s 50th anniversary and to commemorate, they’ve released their new album, Voice of Ages which finds Moloney, Kevin Conneff and Matt Molloy collaborating with some of modern music’s fastest rising artists including Bon Iver, The Decemberists and Paolo Nutini. Also to celebrate the major milestone, they’ll be touring worldwide which will include a one-night performance at the River Rock Casino Resort on October 11, 2012. -

![[Title of the Collection]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5213/title-of-the-collection-2045213.webp)

[Title of the Collection]

Archives of Irish America, Tamiment Library, New York University Mick Moloney Collection of Irish American Music and Popular Culture AIA31.2 Series A: Interviews & Private Performances (including practice & recording sessions) Folder Date Baker, Duck (guitar). Recording session and interview in Philadelphia, PA for the Jul 23, 1978 1979 Kicking Mule release, ―Irish Reels, Jigs, Hornpipes and Airs.‖ (Two CDs – Total length: 00:13:57) Brittingham, Frank (pub owner). Interview recorded in Brittingham’s Irish Pub and May 15, 1991 Restaurant, Lafayette Hill, PA. Brittingham discusses his personal history and his pub, a venue for Irish music in the Philadelphia area. (Two CDs – Total length: 01:04:17) Britton, Tim (uilleann pipes). Recording session at Mick Moloney’s home, 5321 Jan 29, 1977 Germantown Ave., Philadelphia, PA. for the 1979 Rounder release, ―Light Through the Leaves‖. (One CD – Length: 00:18:36) Britton, Tim (uilleann pipes). Recording session and interview in Philadelphia, PA. Jan 3, 1980 (Four CDs – Total length: 00:42:28) Burke, Joe ―Banjo‖ (banjo and voice, b. 1946, Johnstown, Co. Kilkenny, d. Dec, Feb 18, 1977 2003, Albany, New York). Interview at the Bunratty Pub, Bronx, NY. Burke provides biographical and musical information for the sleeve notes of his 1977 Shanachie recording with fiddler Johnny Cronin. (One CD – Length: 00:19:53) Byrne, Tom (flute, b. May 28, 1920, Co.Sligo). Interview in Cleveland, OH. Byrne Apr 27, 1980 discusses his personal and musical experiences in Ireland and Cleveland. (One CD – Length: 00:52:10) Byrne, Tom (flute, b. May 28, 1920, Co.Sligo), McCaffrey, Tom (fiddle, b. -

Blas International Summer School of Irish Traditional Music and Dance

Blas International Summer School of Iris h Traditional Music and Dance Iris h World Academy of Music and Dance University of Limerick FIDDLE TUTORS JOHN CARTY John Carty is one of Ireland’s finest traditional musicians having been awarded the Irish Television station, TG4’s Traditional Musician of the Year in 2003. He joins previous acclaimed winners Matt Molloy (Chieftains flautist), Tommy Peoples (Master Fiddler), Mary Bergin (whistle player, Dordan), Máire Ní Chathasaigh (Harpist) and Paddy Keenan (Uilleann Piper), all of whom are considered to be the leading exponents of their instruments within the Irish tradition. Carty already has three solo fiddle albums, two banjo albums, two group albums and a sprinkling of recorded tenor guitar and flute music recordings under his belt so it’s little wonder he should have joined such elusive ranks. John is a tutor at the Irish World Academy. www.johncartymusic.com Blas International Summer School of Iris h Traditional Music and Dance Iris h World Academy of Music and Dance University of Limerick EILEEN O’BRIEN Eileen is the bearer of a musical dynasty which can be traced back through generations on both sides of her family, the legendary, O’Brien family from Newtown, Nenagh and her mother’s family, the Seerys from Dublin who were founder members of C.C.E. Eileen’s father, Paddy O’Brien established the B/C accordion-playing style in the 1950’s. His innovative style both as a musician and a prolific composer continues to have a profound influence on Irish traditional music. Eileen carries this musical tradition forward through performance, teaching and composition. -

October 1982 Crgnsas (Itts Music Ani 'F.Jntertainment ~Wsfafer Issue 22 · Hac · , Chieftains to Th E Irl~ Re Omlng

BULK RATE u.s. POSTAGE PAID Permit No. 2419 K.C.,MO ;~~KC PITCtI FREE October 1982 CRgnsas (itts Music ani 'f.Jntertainment ~wsfafer Issue 22 · hAC · , Chieftains to Th e Irl~ re omlng. View Stockyards? Bijou & Fine Arts Calendars .................. p. 8, 9,10 Beyond the Beaver ...................... p.ll Juvenile Delinquency Film Festival ...................... p.ll Hollywood Hoopla inKC The Chieftains. Seated are Dereck Bell and Paddll;MQlQ~"~~•• will plQY at The Lyric Theater October 20. Blue Riddim Band ,~...... .J __ ~0m,Qjj~~IH.:!la:!JSH~df Westport and through Rockhurst College Ticket Information Center, 926-4127. by DWight Frizzell Stones on more than one occasion during the Chieftains play, an audience that broke A Sunsplash Smash their last tour. At the historic concert at Slain all pr~vious attendance records set by the Castle in Dublin, Kevin Conneff presented Rolling Stones, the Beatles and the Bee Willi Me What Irish group has performed with the Rolling Stones drummer Charley Watts with Gees. Paddy Maloney modestly told the Rolling Stones, Paul McCartney and a a bodhran. What followed was an impromp Pitch, "It wasn't our gig. The Pope was the Chinese tradition music ensemble, has work Montego Bay, Jamaica. Kansas City's tu jam backstage, after which Watts promis headliner." ed with Stanley Kubrick, holds the world own reggae aficionados, The Blue Riddim ed that he would play the bodhran on at least The Chieftains achieved yet another first record for playing before the largest live au Band, did their bit to ensure themselves a when they played with a traditional Chinese dience, performed for Pope John Paul II and page in musical history.