Michael Daugherty's Bells for Stokowski: Historical Context & Comparative Analysis for Orchestra and Wind Band

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Program Notes

GENEVA CONCERTS presents Friday, November 9, 2012 • 7:30 p.m. Smith Opera House 1 GENEVA CONCERTS, INC. 2012-2013 SEASON Saturday, 13 October 2012, 7:30 p.m. Ballet Jörgen Swan Lake Friday, 9 November 2012, 7:30 p.m. Rochester Philharmonic Orchestra Jeff Tyzik, conductor Kenneth Grant, clarinet Michael Daugherty: Route 66 Jeff Tyzik: IMAGES: Musical Impressions of an Art Gallery Aaron Copland: Clarinet Concerto Leonard Bernstein: On the Waterfront Suite Friday, 25 January 2013, 7:30 p.m. Rochester Philharmonic Orchestra Arild Remmereit, conductor Mark Kellogg, trombone Jennifer Higdon: Machine Ludwig van Beethoven: Symphony No. 1 Lars-Erik Larsson: Concertino for Trombone W.A. Mozart: Symphony No. 40 Friday, 1 March 2013, 7:30 p.m. Swingle Singers Friday, 19 April 2013, 7:30 p.m. Rochester Philharmonic Orchestra Arild Remmereit, conductor Sergej Krylov, violin Margaret Brouwer: Remembrances Henryk Wieniawski: Violin Concerto No. 2 Ludwig van Beethoven: Symphony No. 3, “Eroica” Programs subject to change. Performed at the Smith Opera House 82 Seneca Street, Geneva, New York These concerts are made possible by the New York State Council on the Arts with the support of Governor Andrew Cuomo and the New York State Legislature, and a continuing subscription from Hobart and William Smith Colleges. 2 GENEVA CONCERTS, INC. Friday, November 9, 2012 at 7:30 p.m. Rochester Philharmonic Orchestra Jeff Tyzik, conductor Kenneth Grant, clarinet MICHAEL DAUGHERTY Route 66 JEFF TYZIK Images: Musical Impressions of an Art Museum 1. Convergence (Albert Paley: Convergence,1987) 2. Spirits of Tuol Sleng (Binh Dahn: Found Portraits Collection: from the Cambodian Killing Fields at Tuol Sleng, 2003) 3. -

Temple University Wind Symphony Patricia Cornett, Conductor

Temple University Wind Symphony Patricia Cornett, conductor November 13, 2020 Friday Presented Virtually 7:30 pm Program Mood Swings Interludes composed by members of Dr. Cynthia Folio’s Post-Tonal Theory Class. Performed by Allyson Starr, flute and Joshua Schairer, bassoon. Aria della battaglia (1590) Andrea Gabrieli (1532–1585) ed. Mark Davis Scatterday Love Letter in Miniature Marcos Acevedo-Arús Fratres (1977) Arvo Pärt (b. 1935) arr. Beat Briner Schyler Adkins, graduate student conductor Echoes Allyson Starr Motown Metal (1994) Michael Daugherty (b. 1954) Unmoved Joshua Schairer Petite Symphonie (1885) Charles Gounod (1818–1893) I. Adagio, Allegro II. Andante cantabile III. Scherzo: Allegro moderato IV. Finale: Allegretto Ninety-fourth performance of the 2020-2021 season. Bulls-Eye (2019) Viet Cuong (b. 1990) Musings Spicer W. Carr Drei Lustige Märsche, Op. 44 (1926) Ernst Krenek (1900–1991) Temple University Wind Symphony Patricia Cornett, conductor FLUTE TRUMPET Ruby Ecker-Wylie Maria Carvell Hyerin Kim Anthony Casella Jill Krikorian Daniel Hein Allyson Starr Jacob Springer Malinda Voell Justin Vargas OBOE TROMBONE Geoffrey Deemer Rachel Core Lexi Kroll Jeffrey Dever Brandon Lauffer Samuel Johnson Amanda Rearden Omeed Nyman Sarah Walsh Andrew Sedlacsick CLARINET EUPHONIUM Abbegail Atwater Jason Costello Wendy Bickford Veronica Laguna Samuel Brooks Cameron Harper TUBA Alyssa Kenney Mary Connor Will Klotsas Chris Liounis Alexander Phipps PERCUSSION BASSOON Emilyrose Ristine Rick Barrantes Joel Cammarota Noah Hall Jake Strovel Tracy Nguyen Milo Paperman Collin Odom Andrew Stern Joshua Schairer PIANO SAXOPHONE Madalina Danila Jocelyn Abrahamzon Ian McDaniel GRADUATE ASSISTANTS Sam Scarlett Schyler Adkins Kevin Vu Amanda Dumm HORN Isaac Duquette Kasey Friend MacAdams Danielle O’Hare Jordan Spivack Lucy Smith Program Notes Aria della battaglia Andrea Gabrieli A prominent figure in Renaissance Italy, Andrea Gabrieli acted as principal organist and composer at the St. -

American Academy of Arts and Letters

NEWS RELEASE American Academy of Arts and Letters Contact: Ardith Holmgrain 633 WEST 155 STREET, NEW YORK, NY 10032 [email protected] www.artsandletters.org (212) 368-5900 http://www.artsandletters.org/press_releases/2010music.php THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF ARTS AND LETTERS ANNOUNCES 2010 MUSIC AWARD WINNERS Sixteen Composers Receive Awards Totaling $170,000 New York, March 4, 2010—The American Academy of Arts and Letters announced today the sixteen recipients of this year's awards in music, which total $170,000. The winners were selected by a committee of Academy members: Robert Beaser (chairman), Bernard Rands, Gunther Schuller, Steven Stucky, and Yehudi Wyner. The awards will be presented at the Academy's annual Ceremonial in May. Candidates for music awards are nominated by the 250 members of the Academy. ACADEMY AWARDS IN MUSIC Four composers will each receive a $7500 Academy Award in Music, which honors outstanding artistic achievement and acknowledges the composer who has arrived at his or her own voice. Each will receive an additional $7500 toward the recording of one work. The winners are Daniel Asia, David Felder, Pierre Jalbert, and James Primosch. WLADIMIR AND RHODA LAKOND AWARD The Wladimir and Rhoda Lakond award of $10,000 is given to a promising mid-career composer. This year the award will go to James Lee III. GODDARD LIEBERSON FELLOWSHIPS Two Goddard Lieberson fellowships of $15,000, endowed in 1978 by the CBS Foundation, are given to mid-career composers of exceptional gifts. This year they will go to Philippe Bodin and Aaron J. Travers. WALTER HINRICHSEN AWARD Paula Matthusen will receive the Walter Hinrichsen Award for the publication of a work by a gifted composer. -

Broward Center for the Performing Arts 2018-19 Calendar Listings

July 27, 2018 Maria Pierson/Savannah Whaley Pierson Grant Public Relations 954.776.1999 ext. 225 Jan Goodheart, Broward Center for the Performing Arts 954.765.5814 Note: This season overview is being provided for your use in fall season previews which publish/post/broadcast on September 1 or later. Due to contractual arrangements, the announcement of one or more performances cannot be published by traditional or social media as of July 27, 2018. Embargo information is listed, in red, at the end of the briefs for those performances. Broward Center for the Performing Arts 2018-19 Calendar Listings BrowardCenter.org Facebook.com/BrowardCenter @BrowardCenter #BrowardCenter Instagram.com/BrowardCenter Youtube.com/user/BrowardCenter The Broward Center for the Performing Arts is located at 201 S.W. Fifth Avenue in Fort Lauderdale in the Riverwalk Arts & Entertainment District. Performances are presented in the Au-Rene Theater, Amaturo Theater, Abdo New River Room, Mary N. Porter Riverview Ballroom and the JM Family Studio Theater. Ticketmaster is the only official ticketing service of the Broward Center. Buy tickets online at BrowardCenter.org and Ticketmaster.com; by phone at 954.462.0222; and at the Broward Center’s AutoNation Box Office. Please note that not all shows scheduled for the 2018-19 season are currently on sale and additional performances will be added throughout the season. Print quality images of select performances from the upcoming season, representing all genres, may be downloaded at https://bit.ly/2AgZ45J. One of America’s premier performing arts venues, the Broward Center for the Performing Arts presents more than 700 performances each year to more than 700,000 patrons, showcasing a wide range of exciting cultural programming and events. -

College Orchestra Director Programming Decisions Regarding Classical Twentieth-Century Music Mark D

James Madison University JMU Scholarly Commons Dissertations The Graduate School Summer 2017 College orchestra director programming decisions regarding classical twentieth-century music Mark D. Taylor James Madison University Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/diss201019 Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Taylor, Mark D., "College orchestra director programming decisions regarding classical twentieth-century music" (2017). Dissertations. 132. https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/diss201019/132 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the The Graduate School at JMU Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of JMU Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. College Orchestra Director Programming Decisions Regarding Classical Twentieth-Century Music Mark David Taylor A Doctor of Musical Arts Document submitted to the Graduate Faculty of JAMES MADISON UNIVERSITY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts School of Music August 2017 FACULTY COMMITTEE Committee Chair: Dr. Eric Guinivan Committee Members/ Readers: Dr. Mary Jean Speare Mr. Foster Beyers Acknowledgments Dr. Robert McCashin, former Director of Orchestras and Professor of Orchestral Conducting at James Madison University (JMU) as well as a co-founder of College Orchestra Directors Association (CODA), served as an important sounding-board as the study emerged. Dr. McCashin was particularly helpful in pointing out the challenges of undertaking such a study. I would have been delighted to have Dr. McCashin serve as the chair of my doctoral committee, but he retired from JMU before my study was completed. -

The-Piano-Teaching-Legacy-Of-Solomon-Mikowsky.Pdf

! " #$ % $%& $ '()*) & + & ! ! ' ,'* - .& " ' + ! / 0 # 1 2 3 0 ! 1 2 45 3 678 9 , :$, /; !! < <4 $ ! !! 6=>= < # * - / $ ? ?; ! " # $ !% ! & $ ' ' ($ ' # % %) %* % ' $ ' + " % & ' !# $, ( $ - . ! "- ( % . % % % % $ $ $ - - - - // $$$ 0 1"1"#23." 4& )*5/ +) * !6 !& 7!8%779:9& % ) - 2 ; ! * & < "-$=/-%# & # % %:>9? /- @:>9A4& )*5/ +) "3 " & :>9A 1 The Piano Teaching Legacy of Solomon Mikowsky by Kookhee Hong New York City, NY 2013 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface by Koohe Hong .......................................................3 Endorsements .......................................................................3 Comments ............................................................................5 Part I: Biography ................................................................12 Part II: Pedagogy................................................................71 Part III: Appendices .........................................................148 1. Student Tributes ....................................................149 2. Student Statements ................................................176 -

The GIA Historical Music Series

GIA Publications, Inc. 2018 2018 Music Education Catalog At GIA, we aspire to create innovative resources that communicate the joys of music making and music learning—that delve deeper into what it means to be musical. By working with leading authors who represent the very best the profession has to offer for all levels from preschool through college and beyond, GIA seeks to help music teachers communicate the joy, art, skill, complexity, and knowledge of musicianship. This year we again offer a wide range of new resources for early childhood through college. Scott Edgar explores Music Education and Social Emotional Learning (page 7); the legendary Teaching Music through Performance in Band series moves to Volume 11 (page 8); Scott Rush publishes Habits of a Significant Band Director (page 9) and together with Christopher Selby releases Habits of a Successful Middle Level Musician (pages 10-11). And there’s finally a Habits book for choir directors (page 12). James Jordan gives us four substantial new publications (pages 13-16). There’s also an Ultimate Guide to Creating a Quality Music Assessment Program (page 19). For general music teachers, there is a beautiful collection of folk songs from Bali (page 21), a best- selling book on combining John Feierabend’s First Steps in Music methodology with Orff Schulwerk (page 23), plus the new folk song picture book, Kitty Alone (page 24), just to start. All told, this catalog has 400 pages of resources to explore and enjoy! We’re happy to send single copies of the resources in this catalog on an “on approval” basis with full return privileges for 30 days. -

West Side Story” (Original Cast Recording) (1957) Added to the National Registry: 2008 Essay by Robert L

“West Side Story” (Original cast recording) (1957) Added to the National Registry: 2008 Essay by Robert L. McLaughlin (guest essay)* Original “West Side Story” cast members at recording session (from left: Elizabeth Taylor, Carmen Gutierrez, Marilyn Cooper, Carol Lawrence) “West Side Story” is among the best and most important of Broadway musicals. It was both a culmination of the Rodgers and Hammerstein integrated musical, bringing together music, dance, language and design in service of a powerful narrative, and an arrow pointing toward the future, creating new possibilities for what a musical can be and how it can work. Its cast recording preserves its score and the original performances. “West Side Story’s” journey to theater immortality was not easy. The show’s origins came in the late 1940s when director/choreographer Jerome Robbins, composer Leonard Bernstein, and playwright Arthur Laurents imagined an updated retelling of “Romeo and Juliet,” with the star- crossed lovers thwarted by their contentious Catholic and Jewish families. After some work, the men decided that such a musical would evoke “Abie’s Irish Rose” more than Shakespeare and so they set the project aside. A few years later, however, Bernstein and Laurents were struck by news reports of gang violence in New York and, with Robbins, reconceived the piece as a story of two lovers set against Caucasian and Puerto Rican gang warfare. The musical’s “Prologue” establishes the rivalry between the Jets, a gang of white teens, children mostly of immigrant parents and claimants of a block of turf on New York City’s west side, and the Sharks, a gang of Puerto Rican teens, recently come to the city and, as the play begins, finally numerous enough to challenge the Jets’ dominion. -

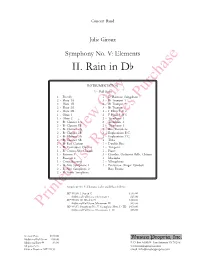

II. Rain in Db

Concert Band Julie Giroux Symphony No. V: Elements II. Rain in Db INSTRUMENTATION 1 - Full Score 1 - Piccolo 1-E Baritone Saxophone 2 - Flute 1A 3-B Trumpet 1 2 - Flute 1B 3-B Trumpet 2 2 - Flute 2A 3-B Trumpet 3 2 - Flute 2B 2 - F Horn 1 & 2 1 - Oboe 1 2 - F Horn 3 & 4 1 - Oboe 2 2 - Trombone 1 2-B Clarinet 1A 2 - Trombone 2 2-B Clarinet 1B 2 - Trombone 3 2-B Clarinet 2A 2 - Bass Trombone 2-B Clarinet 2B 2 - Euphonium B.C. 2-B Clarinet 3A 2 - Euphonium T.C. 2-B Clarinet 3B 4 - Tuba 2-B Bass Clarinet 1 - Double Bass 1-B Contrabass Clarinet 1 - Timpani 1-EPreview Contra Alto Clarinet 1Only - Piano 1 - Bassoon 1 3 - Crotales, Orchestra Bells, Chimes 1 - Bassoon 2 1 - Marimba 1 - Contrabassoon 1 - Vibraphone 2-E Alto Saxophone 1 2 - Percussion (Finger Cymbals, 2-E Alto Saxophone 2 Bass Drum) 2-B Tenor Saxophone Symphony No. V: Elements is also available as follows: MP 99158, I. Sun in C $135.00 Additional Full Score, Movement I $25.00 MP 99160, III. Wind in Eb $200.00 Additional Full Score, Movement III $45.00 PrintedMP 99157, Use Symphony No. RequiresV (Complete, Mvts. I - III) $410.00 Purchase Additional Full Score, Movements I - III $85.00 Score & Parts $140.00 Additional Full Score $30.00 Musica Propria, Inc. Additional Parts @ $3.00 P. O. Box 680006 San Antonio TX 78268 All prices U.S. www.musicapropria.com Edition Number: MP 99159 email: [email protected] About the Composer Julie Ann Giroux was born 1961 in Fairhaven, Massachusetts, and raised in Phoenix, Arizona and Monroe, Louisiana. -

Timeline: Music Evolved the Universe in 500 Songs

Timeline: Music Evolved the universe in 500 songs Year Name Artist Composer Album Genre 13.8 bya The Big Bang The Universe feat. John The Sound of the Big Unclassifiable Gleason Cramer Bang (WMAP) ~40,000 Nyangumarta Singing Male Nyangumarta Songs of Aboriginal World BC Singers Australia and Torres Strait ~40,000 Spontaneous Combustion Mark Atkins Dreamtime - Masters of World BC` the Didgeridoo ~5000 Thunder Drum Improvisation Drums of the World Traditional World Drums: African, World BC Samba, Taiko, Chinese and Middle Eastern Music ~5000 Pearls Dropping Onto The Jade Plate Anna Guo Chinese Traditional World BC Yang-Qin Music ~2800 HAt-a m rw nw tA sxmxt-ib aAt Peter Pringle World BC ~1400 Hurrian Hymn to Nikkal Tim Rayborn Qadim World BC ~128 BC First Delphic Hymn to Apollo Petros Tabouris The Hellenic Art of Music: World Music of Greek Antiquity ~0 AD Epitaph of Seikilos Petros Tabouris The Hellenic Art of Music: World Music of Greek Antiquity ~0 AD Magna Mater Synaulia Music from Ancient Classical Rome - Vol. 1 Wind Instruments ~ 30 AD Chahargan: Daramad-e Avval Arshad Tahmasbi Radif of Mirza Abdollah World ~??? Music for the Buma Dance Baka Pygmies Cameroon: Baka Pygmy World Music 100 The Overseer Solomon Siboni Ballads, Wedding Songs, World and Piyyutim of the Sephardic Jews of Tetuan and Tangier, Morocco Timeline: Music Evolved 2 500 AD Deep Singing Monk With Singing Bowl, Buddhist Monks of Maitri Spiritual Music of Tibet World Cymbals and Ganta Vihar Monastery ~500 AD Marilli (Yeji) Ghanian Traditional Ghana Ancient World Singers -

THE KOSCIUSZKO FOUNDATION CHOPIN PIANO COMPETITION HISTORICAL OVERVIEW in 1949, to Mark the Centennial of the Death of Fryderyk

THE KOSCIUSZKO FOUNDATION CHOPIN PIANO COMPETITION HISTORICAL OVERVIEW In 1949, to mark the centennial of the death of Fryderyk Chopin, the Kosciuszko Foundation’s Board of Trustees authorized a National Committee to encourage observance of the anniversary through concerts and programs throughout the United States. Howard Hansen, then Director of the Eastman School of Music, headed this Committee, which included, among others, Claudio Arrau, Vladimir Horowitz, Serge Koussevitzky, Claire Booth Luce, Eugene Ormandy, Artur Rodzinski, George Szell, and Bruno Walter. The Chopin Centennial was inaugurated by Witold Malcuzynski at Carnegie Hall on February 14, 1949. A repeat performance was presented by Malcuzynski eight days later, on Chopin’s birthday, in the Kosciuszko Foundation Gallery. Abram Chasins, composer, pianist, and music director of the New York Times radio stations WQXR and WQWQ, presided at the evening and opened it with the following remarks: In seeking to do justice to the memory of a musical genius, nothing is so eloquent as a presentation of the works through which he enriched our musical heritage. … In his greatest work, Chopin stands alone … Throughout the chaos, the dissonance of the world, Chopin’s music has been for many of us a sanctuary … It is entirely fitting that this event should take place at the Kosciuszko Foundation House. This Foundation is the only institution which we have in America which promotes cultural relations between Poland and America on a non-political basis. It has helped to understand the debt which mankind owes to Poland’s men of genius. At the Chopin evening at the Foundation, two contributions were made. -

We Have Liftoff! the Rocket City in Space SATURDAY, FEBRUARY 29, 2020 • 7:30 P.M

POPS FOUR We Have Liftoff! The Rocket City in Space SATURDAY, FEBRUARY 29, 2020 • 7:30 p.m. • MARK C. SMITH CONCERT HALL, VON BRAUN CENTER Huntsville Symphony Orchestra • C. DAVID RAGSDALE, Guest Conductor • GREGORY VAJDA, Music Director One of the nation’s major aerospace hubs, Huntsville—the “Rocket City”—has been heavily invested in the industry since Operation Paperclip brought more than 1,600 German scientists to the United States between 1945 and 1959. The Army Ballistic Missile Agency arrived at Redstone Arsenal in 1956, and Eisenhower opened NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in 1960 with Dr. Wernher von Braun as Director. The Redstone and Saturn rockets, the “Moon Buggy” (Lunar Roving Vehicle), Skylab, the Space Shuttle Program, and the Hubble Space Telescope are just a few of the many projects led or assisted by Huntsville. Tonight’s concert celebrates our community’s vital contributions to rocketry and space exploration, at the most opportune of celestial conjunctions: July 2019 marked the 50th anniversary of the Apollo 11 moon-landing mission, and 2020 brings the 50th anniversary of the U.S. Space and Rocket Center, America’s leading aerospace museum and Alabama’s largest tourist attraction. S3, Inc. Pops Series Concert Sponsors: HOMECHOICE WINDOWS AND DOORS REGIONS BANK Guest Conductor Sponsor: LORETTA SPENCER 56 • HSO SEASON 65 • SPRING musical selections from 2001: A Space Odyssey Richard Strauss Fanfare from Thus Spake Zarathustra, op. 30 Johann Strauss, Jr. On the Beautiful Blue Danube, op. 314 Gustav Holst from The Planets, op. 32 Mars, the Bringer of War Venus, the Bringer of Peace Mercury, the Winged Messenger Jupiter, the Bringer of Jollity INTERMISSION Mason Bates Mothership (2010, commissioned by the YouTube Symphony) John Williams Excerpts from Close Encounters of the Third Kind Alexander Courage Star Trek Through the Years Dennis McCarthy Jay Chattaway Jerry Goldsmith arr.