Hr 7, the ''Community Solutions Act of 2001'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Faith Voices Letter

In Support Of Keeping Houses Of Worship Nonpartisan August 16, 2017 Dear Senator: As a leader in my religious community, I am strongly opposed to any effort to repeal or weaken current law that protects houses of worship from becoming centers of partisan politics. Changing the law would threaten the integrity and independence of houses of worship. We must not allow our sacred spaces to be transformed into spaces used to endorse or oppose political candidates. Faith leaders are called to speak truth to power, and we cannot do so if we are merely cogs in partisan political machines. The prophetic role of faith communities necessitates that we retain our independent voice. Current law respects this independence and strikes the right balance: houses of worship that enjoy favored tax-exempt status may engage in advocacy to address moral and political issues, but they cannot tell people who to vote for or against. Nothing in current law, however, prohibits me from endorsing or opposing political candidates in my own personal capacity. Changing the law to repeal or weaken the “Johnson Amendment” – the section of the tax code that prevents tax-exempt nonprofit organizations from endorsing or opposing candidates – would harm houses of worship, which are not identified or divided by partisan lines. Particularly in today’s political climate, engaging in partisan politics and issuing endorsements would be highly divisive and have a detrimental impact on congregational unity and civil discourse. I therefore urge you to oppose any repeal or weakening of the Johnson Amendment, thereby protecting the independence and integrity of houses of worship and other religious organizations in the charitable sector. -

Chicago Neighborhood Resource Directory Contents Hgi

CHICAGO NEIGHBORHOOD [ RESOURCE DIRECTORY san serif is Univers light 45 serif is adobe garamond pro CHICAGO NEIGHBORHOOD RESOURCE DIRECTORY CONTENTS hgi 97 • CHICAGO RESOURCES 139 • GAGE PARK 184 • NORTH PARK 106 • ALBANY PARK 140 • GARFIELD RIDGE 185 • NORWOOD PARK 107 • ARCHER HEIGHTS 141 • GRAND BOULEVARD 186 • OAKLAND 108 • ARMOUR SQUARE 143 • GREATER GRAND CROSSING 187 • O’HARE 109 • ASHBURN 145 • HEGEWISCH 188 • PORTAGE PARK 110 • AUBURN GRESHAM 146 • HERMOSA 189 • PULLMAN 112 • AUSTIN 147 • HUMBOLDT PARK 190 • RIVERDALE 115 • AVALON PARK 149 • HYDE PARK 191 • ROGERS PARK 116 • AVONDALE 150 • IRVING PARK 192 • ROSELAND 117 • BELMONT CRAGIN 152 • JEFFERSON PARK 194 • SOUTH CHICAGO 118 • BEVERLY 153 • KENWOOD 196 • SOUTH DEERING 119 • BRIDGEPORT 154 • LAKE VIEW 197 • SOUTH LAWNDALE 120 • BRIGHTON PARK 156 • LINCOLN PARK 199 • SOUTH SHORE 121 • BURNSIDE 158 • LINCOLN SQUARE 201 • UPTOWN 122 • CALUMET HEIGHTS 160 • LOGAN SQUARE 204 • WASHINGTON HEIGHTS 123 • CHATHAM 162 • LOOP 205 • WASHINGTON PARK 124 • CHICAGO LAWN 165 • LOWER WEST SIDE 206 • WEST ELSDON 125 • CLEARING 167 • MCKINLEY PARK 207 • WEST ENGLEWOOD 126 • DOUGLAS PARK 168 • MONTCLARE 208 • WEST GARFIELD PARK 128 • DUNNING 169 • MORGAN PARK 210 • WEST LAWN 129 • EAST GARFIELD PARK 170 • MOUNT GREENWOOD 211 • WEST PULLMAN 131 • EAST SIDE 171 • NEAR NORTH SIDE 212 • WEST RIDGE 132 • EDGEWATER 173 • NEAR SOUTH SIDE 214 • WEST TOWN 134 • EDISON PARK 174 • NEAR WEST SIDE 217 • WOODLAWN 135 • ENGLEWOOD 178 • NEW CITY 219 • SOURCE LIST 137 • FOREST GLEN 180 • NORTH CENTER 138 • FULLER PARK 181 • NORTH LAWNDALE DEPARTMENT OF FAMILY & SUPPORT SERVICES NEIGHBORHOOD RESOURCE DIRECTORY WELCOME (eU& ...TO THE NEIGHBORHOOD RESOURCE DIRECTORY! This Directory has been compiled by the Chicago Department of Family and Support Services and Chapin Hall to assist Chicago families in connecting to available resources in their communities. -

An Open Letter from Illinois Clergy and Faith Leaders on Marriage

for An Open Letter from Illinois Clergy and Faith Leaders on Marriage We represent people of faith from a variety of communities across our state, and we strongly support the Illinois Religious Freedom and Marriage Fairness Act. We dedicate our lives to fostering faith and compassion, and we work daily to promote justice and fairness for all. Standing on these beliefs, we think that it is morally just to grant equal opportunities and responsibilities to loving, committed same-sex couples. There can be no justification for the law treating people differently on the basis of sexual orientation or gender identity. We accept our gay and lesbian brothers and sisters and recognize that their families need equal recognition and protections. We believe all Illinois couples should have the same civil protections and urge our public officials to support measures to achieve equality. There are differences among our many religious traditions. Some recognize and bless same-sex unions, and some do not. The important thing is that the Religious Freedom and Marriage Fairness Act protects religious freedom and guarantees that all faiths will decide which marriages should be consecrated and solemnized within their tradition. The sacred writings and traditions that we follow carry the messages of love, justice and inclusion. The very basis of marriage is to protect the family, strengthen our communities and advocate compassion. No couple should be excluded from that. We want to promote the common good – that which is best for individuals, couples, families, children, and society. As people of faith and as citizens of Illinois, we ask you to stand for freedom for all of our citizens and support the freedom to marry. -

Elderberries 2020 Winter

www.uurmapa.org E lderberries Volume 36 Number 1 WINTER, 2020 Nationally Known UU Authors Step Out TWO RETIRED COLLEAGUES’ NEW ISSUES STIR READERSHIP Mystery and ministry: Insightful, compassionate a natural evolution of slices of life the power of the word? A new Skinner House book (Oct., 2019) In Time’s Shadow: Stories About JUDITH CAMPBELL, UU community minister, talked to Impermanence, offers a collection of Elderberries about her MARILYN SEWELL’s very short fiction longtime (12 books) Olympia (each about a page or less) on Brown and newer (2018, right) themes of loss and change. Viridienne Greene mysteries, her career(s), and the ongoing Marilyn is Minister Emerita of the First Unitarian ministry of her writing. Church of Portland, OR, where she served as Senior Minister for 17 years before she retired. Judith also presents writing workshops and ‘Writing as Through these compelling readings Spiritual Practice” sessions Marilyn reveals the cultural incongruities both nationally & internation- and inanities that crowd our lives. ally. When she's not traveling We love, we lose, we die, and we and teaching, she makes her might ask, “What’s it all about?” home in Plymouth, MA. “Ministry and murder are CONTINUED, PAGE 8 JUDITH: “Write what you know” is unlikely bedfellows,” said Judith time-honored advice for writers. It is the only way to speak in an authentic (in a Boston Globe interview). MARILYN SEWELL voice. So, what do I know? “But put them together and they From 30 years of college make for a good story and a professing, I know people. And good teaching tool.” Her self- from 20+ years in active ministry, I know the ins and outs and ups and given nicknames include sinister downs of this curious craft, including minister, irreverent reverend, the darker side of human nature. -

Congressional Record—House H2331

March 26, 2003 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — HOUSE H2331 postal carriers, the service responds to more There was no objection. Mr. DAVIS of Illinois. Mr. Speaker, I than 1,000 postal-related assaults and credit Mr. DUNCAN. Mr. Speaker, I yield yield myself such time as I might con- threats, 75,000 complaints of consumer mail myself such time as I may consume. sume. fraud, and it arrests 12,000 criminal suspects Mr. Speaker, it is a real honor and (Mr. DAVIS of Illinois asked and was for mail-related crimes each year. privilege for me to bring this par- given permission to revise and extend Today, my colleagues have a special oppor- ticular legislation to the floor at this his remarks.) tunity to honor the entire United States Postal time because Floyd Spence was a close, Mr. DAVIS of Illinois. Mr. Speaker, Service, by naming a postal facility after one personal friend of mine and one of the H.R. 917, which names a postal facility of their own heroes. With the passage of H.R. greatest Members this body has ever located at 1830 South Lake Drive in 825, The House of Representatives will re- seen. I had the privilege of traveling Lexington, South Carolina, after Floyd name the Moraine Valley, Illinois Post Office several different places with Congress- Spence, was introduced on February 25, the Michael J. Healy Post Office. man Spence and working with him on 2003, by the gentleman from South Finally, I would like to recognize Joan many different pieces of legislation. Carolina (Mr. WILSON). Healy, Michael’s mother, his brother David, H.R. -

Man of the House

Walkthrough - - (7.30AM) breakfast talk with mom, for earn some points. - (8.30AM) Talk with Sis (Ashley) twice, and open new option. - For now MC only need talk with Veronica in the Kitchen (9.00 - 10.00AM) and open new option. - In the beggin MC need go in his Room and in the computer and have Online Course, do it till have the message that MC –have mastered completely - (8.00-12.00AM) - MC need go in the pizzeria and Work (12.00 -15.00AM) – doing this, MC can open new options, and get some itens. - (15.00PM) Teaching Sis in Her Bedroom, twice. - (18.00PM) Dinner with everyone. - (19.00) Talk with Mom in the kitchen, for earn some points. - (19.00 – 19.30PM) See movies with Sis. - (21,00PM) MC giving for Mom the -rub foot-, after –Try to move- (MC need give her some Wine) -Buy in the Supermarket - - - (22.00PM) MC need give Goodnight for Sis (Ashley) - (6.00AM) Go to the rooftop, see and talk with Mom. - - The Rooftop - - Advice: Walking or travel with bus, taxi or even going with Veronica’s car, is a random event but MC can find some itens and some advertising that open Pizzeria, Casino and maybe others location (in the next version). - And for open Health Club, MC need talk with Mom in the rooftop (6.00AM) - In the morning new event (7.00AM) MC need sleep and wake up at 7.00Am (before sleep need heard the phone in the Mom's bedroom, 22.00PM Mom and Aunt talking) - - Ashley - (8.30AM) - Breakfast - (15.00PM) - Teaching (Twice, till options are open) - (19.00PM) - See movies (When Horror movie are open, new option in the night) (19.30PM when MC talk with Mom) - (21.00PM) - Bathroom (New scenes with Sis) – You can alternate with Mom’s scenes – one day Sis, another Mom. -

Guide to the Hyde Park and Kenwood Interfaith Council Records 1911-1993

University of Chicago Library Guide to the Hyde Park and Kenwood Interfaith Council Records 1911-1993 © 2008 University of Chicago Library Table of Contents Acknowledgments 3 Descriptive Summary 3 Information on Use 3 Access 3 Citation 3 Historical Note 3 Scope Note 4 Related Resources 4 Subject Headings 4 INVENTORY 4 Descriptive Summary Identifier ICU.SPCL.HPKIC Title Hyde Park and Kenwood Interfaith Council. Records Size 6.5 linear feet (12 boxes) Repository Special Collections Research Center University of Chicago Library 1100 East 57th Street Chicago, Illinois 60637 U.S.A. Abstract This collection contains the records of the Hyde Park and Kenwood Interfaith Council, from 1911-1993. Included are administrative records such as minutes, correspondence, budgets and directories of membership. This collection also contains general subject files covering Council projects and affiliated institutions. Acknowledgments Preservation of this collection was supported with a generous gift from the University of Chicago Service League. Information on Use Access Open for research. No restrictions Citation When quoting material from this collection, the preferred citation is: Hyde Park and Kenwood Interfaith Council. Records, [Box #, Folder #], Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library Historical Note Founded in 1911, the Hyde Park and Kenwood Interfaith Council’s purpose has remained unchanged; they strive for “the increased efficiency of the spiritual forces of our community along cooperative lines.” The Council has evolved over the years to include a greater variety of religious traditions. It began in 1911 as “the Council of Hyde Park Churches.” In 1929, the name changed first to “The Council of Hyde Park and Kenwood Churches” and changed again in 1939 to “The Council of Hyde Park and Kenwood and Synagogues.” If finally became the Hyde Park and Kenwood Interfaith Council in 1984. -

San Diego Health & Exercise Survey

THIS SURVEY SHOULD BE COMPLETELY FILLED OUT BY THE FOLLOWING PERSON, WHO MUST BE I' AT LEAST 18 YEARS OLD: D The lady of the house. If the lady of D The man of the house. If the man of the house is not available, then the the house is not available, then the man of the house should fill it out. lady of the house should 'fill it out. o Check here if you want a free 2 week pass to Family Fitness Center. Please read each question carefully and answer it to the best of your ability. Do not spend too much time on any question. Your answers will be kept in strictest confidence. SAN DIEGO HEALTH & EXERCISE SURVEY 1. How is your health? (PLEASE CHECK ONE) VERY GOOD_l GOOD 2 AVERAGE _3 POOR _4 VERY POOR_5 2. Do you need to limit your physical activity because of an illness, NO 1 injury or handicap? YES, BECAUSE OF TEMPORARY ILLNESS _ 2 (CHECK ONE) YES, BECAUSE OF LONG-TERM ILLNESS _ 3 YES, BECAUSE OF TEMPORARY INJURY _ 4 YES, BECAUSE OF LONG-TERM INJURY . OR HANDICAP. _ 5 3. Are you being treated by a doctor for any medical condition? NO _1 If yes, please explain _ YES _2 4. Have either of your parents ever had a heart attack or stroke before NO 1 they were 55 years old? YES _2 DON'T KNOW _3 5. How often do you eat the following foods? (MARK ONE NUMBER FOR EACH ITEM) Never or Several Few Times About Once Times Few Times Almost a Year a Month a Month a Week ~ 1. -

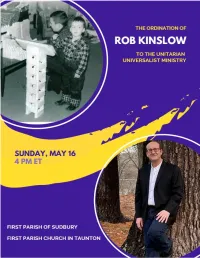

Robk Ordination OOS FINAL Rev2

ORDER OF SERVICE Processional All Creatures of the Earth and Sky Words: Attributed to St. Francis of Assisi Music: Ralph Vaughan Williams Performed by the First Parish of Sudbury Choir Welcome Rev. Dr. Marjorie Matty Call to Worship Rev. Christana Wille McKnight Chalice Lighting Jay Kinslow Dan Kinslow Stephanie Deerwester Invitation to Generosity Rev. Tera Klein Offertory Sure on This Shining Night Words: James Agee Music: Morten Lauridsen Performed by the First Parish of Sudbury Choir Prayer Sarah Donnell Emily Drummond Li Kynvi Lauren Levwood Amanda Schuber Reading Rev. Beverly Waring Musical Response The River Words and music: Coco Love Alcorn Performed by the First Parish Church in Taunton Ensemble Homily Rev. Andrea Greenwood and Rev. Mark W. Harris Musical Response Swimming to the Other Side Words and music: Pat Humphries Performed by the First Parish Church in Taunton Ensemble Act of Ordination Valerie Tratnyek Mary Vaeni ACT OF ORDINATION With microphones remaining muted, please join in these words as directed: Members of First Parish of Sudbury: We, the members of First Parish of Sudbury, of Sudbury, Massachusetts … Members of First Parish Church in Taunton: We, the members of the First Parish Church in Taunton, of Taunton, Massachusetts … All members of both congregations: By the authority of our living tradition, we joyfully ordain you, Reverend Robert Patrick Kinslow, to the Unitarian Universalist ministry. Live into this call. May you minister from your whole self: heart and mind, body and spirit. May you always speak the truth as you know it with courage and wisdom, demonstrate grace, gentleness and good humor, celebrate the mystery and wonder of life, share in the joys and sorrows of our human condition, embody the living tradition of our faith, and above all, serve the world with compassion and love. -

Honoring Who've Made a Difference

honoring Who’ve Made a 4Difference Business and Professional People for the Public Interest 4o Who’ve Made a Difference Awards Business and Professional People for the Public Interest 4oth Anniversary Celebration The Fairmont Chicago May 1, 2oo9 INTRODUCTION As our 40th Anniversary approached, BPI’s Board of It is BPI’s privilege to introduce our 40 Who’ve Made Directors decided to focus our celebration on the a Difference—a stunning kaleidoscope of vision and amazing range and richness of public interest work in accomplishment by a diverse group of individuals our region by shining a spotlight on people whose representing many different fields of endeavor— civil leadership, vision and courage have made a significant rights, education, law, housing, the arts, healthcare. difference in the lives of others—people whose efforts We honor their individual commitment and achievement derive from and contribute to the social justice values as we are inspired by their collective contribution to to which BPI has been dedicated for four decades. the people of the Chicago region. BPI issued an open Call for Nominations and convened How to estimate the impact of their efforts? As you read a Selection Committee of respected leaders from various through these brief narratives, you might consider what fields. The Committee faced a difficult challenge in life here would be like without their work. There would fulfilling its mandate of choosing “40 Who’ve Made a be significantly less equality of opportunity in housing, Difference” from scores of exceptional nominees. education and healthcare…less cultural vitality and After hours of research, review and deliberation, the opportunity to experience it…less access to justice.. -

Congressional Record-·House

1900. CONGRESSIONAL RECORD-·HOUSE. 189 By Mr. HOFFECKER: A bill (H. R.12507) granting an increase By Mr. ROBINSON of Indiana: Petition of Advance Grange, of pension to Ezekiel Dawson-to the Committee on Invalid Pen No. 2100, Patrons of Husbandry, of Fremont, Ind., favoring pure sions. food legislation-to the Committee on Agriculture. By Mr. RANSDELL: A bill (H. R. 12508) for the relief of John By Mr. RYAN of New York: Petition of Rev. George B. New McDonnell-to the Committee on Military Affairs. comb and others, of Buffalo, N. Y., in favor of the anti-polygamy By Mr. KLEBERG: A bill (H. R. 12509) for the relief of Maria. amendment to the Constitution-to the Committee on the Judi Thornton, residuary legatee of Richard Miller, deceased-to the ciary. Committee on War Claims. By Mr. SHACKLEFORD: Petition of the estate of John W. Livesay, deceased, of Missouri, for reference of war claim to the Court of Claims-to the Committee on War Claims. PETITIONS, ETC. By Mr. SIBL.EY: Petitions of druggists of Warren County, Pa., Under clause 1 of Rule XXII, the following petitions and papers for the repeal of the special tax on proprietary medicines-to the were laid on the Clerk's desk and referred as follows: Committee on Ways and Means. By Mr. ACHESON: Petition of J. D. Moffat and other citizens Also, petition of citizens of Warren, Pa., in favor of the anti of Washington County, Pa., in favor of an amendment to the polygamy amendment to the Constitution-to the Committee on Constitution against polygamy-to the Committee on the Judi the Judiciary. -

Hartford Public Library DVD Title List

Hartford Public Library DVD Title List # 24 Season 1 (7 Discs) 2 Family Movies: Family Time: Adventures 24 Season 2 (7 Discs) of Gallant Bess & The Pied Piper of 24 Season 3 (7 Discs) Hamelin 24 Season 4 (7 Discs) 3:10 to Yuma 24 Season 5 (7 Discs) 30 Minutes or Less 24 Season 6 (7 Discs) 300 24 Season 7 (6 Discs) 3-Way 24 Season 8 (6 Discs) 4 Cult Horror Movies (2 Discs) 24: Redemption 2 Discs 4 Film Favorites: The Matrix Collection- 27 Dresses (4 Discs) 40 Year Old Virgin, The 4 Movies With Soul 50 Icons of Comedy 4 Peliculas! Accion Exploxiva VI (2 Discs) 150 Cartoon Classics (4 Discs) 400 Years of the Telescope 5 Action Movies A 5 Great Movies Rated G A.I. Artificial Intelligence (2 Discs) 5th Wave, The A.R.C.H.I.E. 6 Family Movies(2 Discs) Abduction 8 Family Movies (2 Discs) About Schmidt 8 Mile Abraham Lincoln Vampire Hunter 10 Bible Stories for the Whole Family Absolute Power 10 Minute Solution: Pilates Accountant, The 10 Movie Adventure Pack (2 Discs) Act of Valor 10,000 BC Action Films (2 Discs) 102 Minutes That Changed America Action Pack Volume 6 10th Kingdom, The (3 Discs) Adventure of Sherlock Holmes’ Smarter 11:14 Brother, The 12 Angry Men Adventures in Babysitting 12 Years a Slave Adventures in Zambezia 13 Hours Adventures of Elmo in Grouchland, The 13 Towns of Huron County, The: A 150 Year Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad Heritage Adventures of Mickey Matson and the 16 Blocks Copperhead Treasure, The 17th Annual Lane Automotive Car Show Adventures of Milo and Otis, The 2005 Adventures of Pepper & Paula, The 20 Movie