Page 1 1 R -~-~, • J 'A STUDY of QA~ARÏ-BRITISH RELAT.IONS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Significant Increase in Home-Based Businesses

BUSINESS | 21 SPORT | 27 MHPS to remain Dominant Djokovic Qatar's active wins Shanghai partner: Muyama Masters title Monday 15 October 2018 | 6 Safar I 1440 www.thepeninsula.qa Volume 23 | Number 7680 | 2 Riyals Significant increase in QU’s stellar performance in THE World University Rankings 2019 Total performance indicators home-based businesses used for comparison MOHAMMAD SHOEB The second edition edition, which witnessed the QU placed at THE PENINSULA QU ranked QU achieved in QU was of ‘Made at Home’ participation of 144 local home- 332nd place QS Top 50 under based businesses. The event tar- first in ranked 52 in exhibition will run International in QS World 50 ranking The Asia DOHA: The Minister of Admin- geted a variety of sectors which University among the best istrative Development, Labour were art crafts, technologies, Outlook University until October 20 at Rankings young and Social Affairs H E Dr Issa bin Doha Exhibition and food & beverage, jewelry with Indicator Rankings in Saad Al Jafali Al Nuaimi, who total sales reaching QR2.5m. The 2019 universities Feb 2018 formally inaugurated the second Convention Center. exhibition was attended by more edition of ‘Made at Home’ exhi- than 15,000 visitors across bition yesterday, said that the several nationalities. expo has witnessed a remarkable October 20 at Doha Exhibition The expo is being held under development in all sectors and and Convention Center (DECC), the patronage of H E Sheikha Al products, where over 185 partic- where local micro-businesses and Mayassabint Hamad bin Khalifa ipants are showcasing their home-based manufactures are Al Thani, Chairperson of Qatar products and services. -

Genomic Citizenship: Peoplehood and State in Israel and Qatar

Genomic Citizenship: Peoplehood and State in Israel and Qatar The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:40049986 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Genomic Citizenship: Peoplehood and State in Israel and Qatar A dissertation presented by Ian Vincent McGonigle to The Committee on Middle Eastern Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of Anthropology and Middle Eastern Studies Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts March 2018 © 2018 Ian Vincent McGonigle All rights reserved. Jean Comaroff and Steve Caton Ian Vincent McGonigle Genomic Citizenship: Peoplehood and State in Israel and Qatar Abstract This dissertation describes basic genetic research and biobanking of ethnic populations in Israel and Qatar. I track how biomedical research on ethnic populations relates to the political, economic, legal, and historical context of the states; to global trends in genetic medicine; and to the politics of identity in the context of global biomedical research. I describe the ways biology is becoming a site for negotiating identity in ethnic genetics, in discourse over rights to citizenship, in rare disease genetics, and in personalized medicine. The core focus of this work is the way the molecular realm is an emergent site for articulations of ethnonational identities in the contemporary Middle East. -

Cultural Heritages of Water the Cultural Heritages of Water in the Middle East and Maghreb ______

Cultural Heritages of Water The cultural heritages of water in the Middle East and Maghreb __________________________________________________________________________ Les patrimoines culturels de l’eau Les patrimoines culturels de l’eau au Moyen-Orient et au Maghreb THEMATIC STUDY | ÉTUDE THEMATIQUE Second edition | Deuxième édition Revised and expanded | Revue et augmentéé International Council on Monuments and Sites 11 rue du Séminaire de Conflans 94220 Charenton-le-Pont France © ICOMOS, 2017. All rights reserved ISBN 978-2-918086-21-5 ISBN 978-2-918086-22-2 (e-version) Cover (from left to right) Algérie - Vue aérienne des regards d’entretien d’une foggara (N.O Timimoune, Georges Steinmetz, 2007) Oman - Restored distributing point (UNESCO website, photo Jean-Jacques Gelbart) Iran - Shustar, Gargar Dam and the areas of mills (nomination file, SP of Iran, ICHHTO) Tunisie - Vue de l’aqueduc de Zaghouan-Carthage (M. Khanoussi) Turkey - The traverten pools in Pamukkale (ICOMOS National Committee of Turkey) Layout : Joana Arruda and Emeline Mousseh Acknowledgements In preparing The cultural heritages of water in the Middle East and Maghreb Thematic Study, ICOMOS would like to acknowledge the support and contribution of the Arab Regional Centre for World Heritage and in particular H.E. Sheikha Mai bint Mohammed AI Khalifa, Minister of Culture of the Kingdom of Bahrain; Pr. Michel Cotte, ICOMOS advisor; and Regina Durighello, Director of the World Heritage Unit. Remerciements En préparant cette étude thématique sur Les patrimoines culturels de l'eau au Moyen-Orient et au Maghreb, l’ICOMOS remercie pour son aide et sa contribution le Centre régional arabe pour le patrimoine mondial (ARC-WH) et plus particulièrement S. -

Download Complete List of References

LIST OF REFERENCES Latest update 29/09/2021 LIST OF REFERENCES Index Shopping Malls 3 Convention Centers 16 Sport Centers 21 Corporate 25 Hospitals 34 Metro and Train Networks 41 Universities 45 Airports 52 Others 57 Tunnels 69 Logistics Centers 70 Hospitality 72 LDA Audio Tech. Severo Ochoa, 31, 29590 Málaga. Tel. +34 952 028 805. [email protected] Latest update 29/09/2021 2 LIST OF REFERENCES Shopping Malls Madaba City Mall REFERENCE: CLIENT: Madaba city mall PLACE: Madaba, Jordan DATE: 2020 Madaba City Mall is the first and largest mall in the Governorate of Madaba, which is designed with the latest sophisticated engineering style, and contains many well-known brands and international restaurants. This Mall is strategically located between hotels, the commercial market and archaeological areas. In order to provide the best audio solution, our partner FIRE EXPERTS used more than 400 speakers alongside a NEO8060 and a NEO Extension. Read more Al Faisaliah Mall REFERENCE: CLIENT: Al Khozama Management Company PLACE: Riyadh, Saudi Arabia DATE: 2019 Riyadh is the capital and the largest city of Saudi Arabia, an attractive tourist and business destination that has become the most important economic center in the Middle East. Al Faisaliah Mall was built in 2000 and introduced a new concept of high-level shopping in the area. Read more LDA Audio Tech. Severo Ochoa, 31, 29590 Málaga. Tel. +34 952 028 805. [email protected] Latest update 29/09/2021 3 LIST OF REFERENCES El Corte Inglés parking Valladolid REFERENCE: CLIENT: El Corte Inglés PLACE: Valladolid, Spain DATE: 2018 The Zorrilla mall is a large five-storey building located in one of the main commercial streets of Valladolid (Spain) with an El Corte Inglés shopping center that includes fashion and accessories, electronics, home and decoration, culture, sports and supermarket departments. -

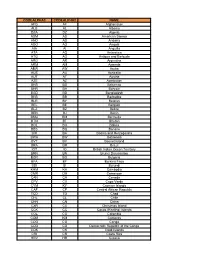

CODEALPHA3 CODEALPHA2 NAME AFG AF Afghanistan ALB AL

CODEALPHA3 CODEALPHA2 NAME AFG AF Afghanistan ALB AL Albania DZA DZ Algeria ASM AS American Samoa AND AD Andorra AGO AO Angola AIA AI Anguilla ATA AQ Antarctica ATG AG Antigua and Barbuda ARG AR Argentina ARM AM Armenia ABW AW Aruba AUS AU Australia AUT AT Austria AZE AZ Azerbaijan BHS BS Bahamas BHR BH Bahrain BGD BD Bangladesh BRB BB Barbados BLR BY Belarus BEL BE Belgium BLZ BZ Belize BEN BJ Benin BMU BM Bermuda BTN BT Bhutan BOL BO Bolivia BES BQ Bonaire BIH BA Bosnia and Herzegovina BWA BW Botswana BVT BV Bouvet Island BRA BR Brazil IOT IO British Indian Ocean Territory BRN BN Brunei Darussalam BGR BG Bulgaria BFA BF Burkina Faso BDI BI Burundi KHM KH Cambodia CMR CM Cameroon CAN CA Canada CPV CV Cape Verde CYM KY Cayman Islands CAF CF Central African Republic TCD TD Chad CHL CL Chile CHN CN China CXR CX Christmas Island CCK CC Cocos (Keeling) Islands COL CO Colombia COM KM Comoros COG CG Congo COD CD Democratic Republic of the Congo COK CK Cook Islands CRI CR Costa Rica HRV HR Croatia CUB CU Cuba CUW CW Cura?§ao CYP CY Cyprus CZE CZ Czech Republic DNK DK Denmark DJI DJ Djibouti DMA DM Dominica DOM DO Dominican Republic TLS TL Timor-Leste ECU EC Ecuador EGY EG Egypt SLV SV El Salvador GNQ GQ Equatorial Guinea ERI ER Eritrea EST EE Estonia ETH ET Ethiopia FLK FK Falkland Islands (Malvinas) FRO FO Faroe Islands FJI FJ Fiji FIN FI Finland FRA FR France GUF GF French Guiana PYF PF French Polynesia ATF TF French Southern Territories GAB GA Gabon GMB GM Gambia GEO GE Georgia DEU DE Germany GHA GH Ghana GIB GI Gibraltar GRC GR Greece GRL -

Qatar Cultural Field Guide

FOR OffICIAL USE ONLY QATAR CULTURAL FIELD GUIDE Dissemination and use of this publication is restricted to official military and government personnel from the United States of America, United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, and other countries as required and desig- nated for support of coalition operations. The photos and text reproduced herein have been extracted solely for re- search, comment, and information reporting, and are intended for fair use by designated personnel in their official duties, including local reproduc- tion for training. Further dissemination of copyrighted material contained in this docu ment, to include excerpts and graphics, is strictly prohibited under Title 17, U.S. Code. Published: August 2010 Prepared by: Marine Corps Intelligence Activity, 2033 Barnett Avenue, Quantico, VA 22134-5103 Comments and Suggestions: [email protected] To order additional copies of this field guide, call (703) 784-6167, DSN: 278-6167. DOD-2634-QAT-016-10 FOR OffICIAL USE ONLY Foreword The Qatar Cultural Field Guide is designed to provide deploying military personnel an overview of Qatar’s cultural terrain. In this field guide, Qatar’s cultural history has been synopsized to capture the more significant aspects of the country’s cultural environment, with emphasis on factors having the greatest potential to impact operations. The field guide presents background information to show the Qatar mind-set through its history, language, and religion. It also con- tains practical sections on lifestyle, customs and habits. For those seeking more extensive information, MCIA produces a series of cultural intelligence studies on Qatar that explore the dynamics of Qatar culture at a deeper level. -

Saudi Arabia, Yemen, Oman, United Arab Emirates, Qatar, Bahrain

International Council on Monuments and Sites 11 rue du Séminaire de Conflans 94220 Charenton-le-Pont France © ICOMOS, 2015. All rights reserved ISBN 978-2-918086-17-8 (e-version) Cover (from left to right) Algérie - Vue aérienne des regards d’entretien d’une foggara (N.O Timimoune, Georges Steinmetz, 2007) Oman - Restored distributing point (UNESCO website, photo Jean-Jacques Gelbart) Iran - Shushtar, Gargar Dam and the areas of mills (nomination file, SP of Iran, ICHHTO) Tunisie - Vue de l’aqueduc de Zaghouan-Carthage (M. Khanoussi) Turkey - The traverten pools in Pamukkale (ICOMOS National Committee of Turkey) Layout: Trina Moine Acknowledgements In preparing The cultural heritages of water in the Middle East and Maghreb Thematic Study, ICOMOS would like to acknowledge the support and contribution of the Arab Regional Centre for World Heritage and in particular H.E. Sheikha Mai bint Mohammed AI Khalifa, Minister of Culture of the Kingdom of Bahrain; Pr. Michel Cotte, ICOMOS advisor; and Regina Durighello, Director of the World Heritage Unit. Remerciements En préparant cette étude thématique sur Les patrimoines culturels de l'eau au Moyen-Orient et au Maghreb, l’ICOMOS remercie pour son aide et sa contribution le Centre régional arabe pour le patrimoine mondial (ARC-WH) et plus particulièrement S. Exc. Mme Sheikha Mai bint Mohammed AI Khalifa, Ministre de la culture, Royaume de Bahreïn, le Pr. Michel Cotte, conseiller de l’ICOMOS et Regina Durighello, directeur de l’Unité du patrimoine mondial. Table of contents ⏐ Table des matières -

Education for a New Era

THE ARTS This PDF document was made available CHILD POLICY from www.rand.org as a public service of CIVIL JUSTICE the RAND Corporation. EDUCATION ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT Jump down to document6 HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit NATIONAL SECURITY research organization providing POPULATION AND AGING PUBLIC SAFETY objective analysis and effective SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY solutions that address the challenges SUBSTANCE ABUSE facing the public and private sectors TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY around the world. TRANSPORTATION AND INFRASTRUCTURE WORKFORCE AND WORKPLACE Support RAND Purchase this document Browse Books & Publications Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore RAND-Qatar Policy Institute View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non- commercial use only. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents. This product is part of the RAND Corporation monograph series. RAND monographs present major research findings that address the challenges facing the public and private sectors. All RAND mono- graphs undergo rigorous peer review to ensure high standards for research quality and objectivity. Education for a New Era Design and Implementation of K–12 Education Reform in Qatar Dominic J. Brewer • Catherine H. Augustine • Gail L. Zellman • Gery Ryan Charles A. Goldman • Cathleen Stasz • Louay Constant Prepared for the Supreme Education Council Approved for public release, distribution unlimited The research described in this report was prepared for the Supreme Education Council and conducted within RAND Education and the RAND-Qatar Policy Institute, programs of the RAND Corporation. -

Al Shamal Municipality Vision and Development Strategy

Al Shamal Municipality Vision and Development Strategy Volume 1 of the Al Shamal Municipality Spatial Development Plan JUNE 2014 QAT AR NATIONAL MASTER PLAN Contents 1.0 General Requirements and Procedures ...................................................................... 2 1.1 Al Shamal Municipality Spatial Development Plan ...................................................... 2 1.2 Purpose and Effect of the MSDP ................................................................................ 2 1.3 Management of Development ..................................................................................... 2 1.4 QNDF Context ............................................................................................................. 3 2.0 Al Shamal Municipality ................................................................................................ 4 2.1 Location and Description ............................................................................................. 4 2.2 Population and Employment Growth Expectations 2010 – 2032 ................................ 4 2.3 Key Planning Issues .................................................................................................... 5 2.4 Municipality Planning Objectives ................................................................................. 5 3.0 Vision and Development Strategy ............................................................................. 10 3.1 Vision 2032 ............................................................................................................... -

Travel to CNA-Qatar College of the North Atlantic–Qatar Campus Map

Travel to CNA-Qatar College of the North Atlantic–Qatar Campus Map Overflow Parking and Sports Fields 1 Gate Overflow Parking for Bldgs 19, 20 Tennis Parking and Court Sports Field Sports Field Building 17 Building 19, 20 Female Rec Cen. HEALTH SCIENCE Bldg 18 Building 13 Male ehouse TY Cafeteria Rec r Building 16 Centre Wa Parking for Gate 3 Bldgs Building 10 es 10, 11, 12 Building 12 Offic Building 5 ENGINEERING INFO Building 11 BUSINESS & SECURI TECH re Inner 6 Building 8 Parking for Bldgs Oil & Gas 9, 14, 18 Courtyard Bldg 2 Booksto Building 7 Offices Plant Gate Building 5 Building 1 Building 3 AUDITORIUM ADMINISTRATION, FINANCE, ACADEMICS MARKETING Parking for Bldgs 5, 7 Parking for Bldgs 1, 2 Administration & Visitor Building 3 Staff Parking Table of Contents Welcome-Marhaba! . 2 Before You Leave Canada . 2 Arrival . 3 Civic Addresses of Living Communities . 3 Accommodations for CNA-Q Employees . 4 State of Qatar . 4 Time . 6 Language . 6 Population . 6 Working Days and Hours . 6 Qatar Flag . 7 Currency . 7 Weather . 7 Doha International Airport (DOH) Temperature Chart . 8 Personal Safety in Qatar . 8 Skills That Make a Difference . 10 Banking . 10 Telephone/Internet Services . 11 Shopping . 12 Malls and Centres . 12 Souqs and Markets . 13 Grocery Stores . 13 Newspapers . 13 Dining Out in Qatar . 14 Appropriate Behaviour and Dress . 15 Behaviour Guidelines . 15 Dress Guidelines . 16 “Workout” Clothes . 16 International Travel Checklist - Qatar . 17 Trip Preparation Check list . 17 Personal Items . 18 First Aid . 18 Food . 18 Electrical devices . 18 Advice from Foreign Affairs and International Trade Canada .