Fall 1992 215 Agamemnon and Theatre Du Soleil

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sir Terence Rattigan, CBE 1911 – 1977

A Centenary Service of Celebration for the Life and Work of Sir Terence Rattigan, CBE 1911 – 1977 “God from afar looks graciously upon a gentle master.” St Paul’s Covent Garden Tuesday 22nd May 2012 11.00am Order of Service PRELUDE ‘O Soave Fanciulla’ from La Bohème by G. Puccini Organist: Simon Gutteridge THE WELCOME The Reverend Simon Grigg The Lord’s Prayer Our Father, who art in heaven, hallowed be thy name. Thy kingdom come, thy will be done, on earth as it is in heaven. Give us this day our daily bread; and forgive us our trespasses, as we forgive them that trespass against us. And lead us not into temptation, but deliver us from evil. For thine is the kingdom, the power and the glory, for ever and ever. Amen. TRIBUTE DAVID SUCHET, CBE written by Geoffrey Wansell 1 ARIA ‘O Mio Babbino Caro’ from Gianni Schicchi by G. Puccini CHARLOTTE PAGE HYMN And did those feet in ancient time Walk upon England's mountains green? And was the holy Lamb of God On England's pleasant pastures seen? And did the countenance divine Shine forth upon our clouded hills? And was Jerusalem builded here Among those dark satanic mills? Bring me my bow of burning gold! Bring me my arrows of desire! Bring me my spear! O clouds, unfold! Bring me my chariot of fire! I will not cease from mental fight, Nor shall my sword sleep in my hand, Till we have built Jerusalem In England's green and pleasant land. ADDRESS ‘The Final Test’ SIR RONALD HARWOOD, CBE 2 HYMN I vow to thee, my country, all earthly things above, Entire and whole and perfect, the service of my love: The love that asks no question, the love that stands the test, That lays upon the altar the dearest and the best; The love that never falters, the love that pays the price, The love that makes undaunted the final sacrifice. -

Ariane Mnouchkine

The Théâtre du Soleil Ariane Mnouchkine, born 3rd March 1939 at Boulogne-sur-Seine, is the director of theatre company, the Théâtre du Soleil, which she founded in 1964 with her fellows of the ATEP (The Theatre Association of the Students of Paris). In 1970, the Théâtre du Soleil created 1789 at the Piccolo Teatro in Milan, where Giorgio Strehler warmly welcomed the young company and gave them his support. The company then went on to choose its home at the Cartoucherie, a former bullet-making factory, in the Bois de Vincennes on the outskirts of Paris. The Cartoucherie enabled the troupe to expand on the notion of the theatre simply as architectural institution and allowed them to focus on the concept of the theatre being a place of haven rather than just complying with the traditional architectural notions of a theatre building, and all this at a time when urban change and development in France was transforming the place of man in the city and the place of theatre in the city. In the Cartoucherie, the Théâtre du Soleil found the necessary tool to create and present the type of popular yet high-quality theatre dreamed of by Antoine Vitez and Jean Vilar. The troupe invented new ways of working and privileged collectively devised work, its aim being to establish a new relationship with its audience and distinguishing itself from bourgeois theatre in order to create a high-quality theatre for the people. From the 1970s onwards, the troupe became one of France's major theatre companies, both because of the number of artists working in it (more than seventy people a year) and because of its glowing international reputation. -

Ariane Mnouchkine New York, July 22, 2005

This page intentionally left blank We are the first people who are leaving nothing for our children – and America is leading the charge.We are at war against our children. Ariane Mnouchkine New York, July 22, 2005 Frontispiece Ariane Mnouchkine and the Théâtre du Soleil at the Cartoucherie de Vincennes during the run of The Shakespeare Cycle, 1981 ARIANE MNOUCHKINE Routledge Performance Practitioners is a series of introductory guides to the key theater-makers of the last century. Each volume explains the background to and the work of one of the major influences on twentieth- and twenty-first-century performance. Ariane Mnouchkine, the most significant living French theater director, has devised over the last forty years a form of research and creation with her theater collective, Le Théâtre du Soleil, that is both engaged with contemporary history and committed to reinvigorating theater by foregrounding the centrality of the actor.This is the first book to combine: G an overview of Mnouchkine’s life, work and theatrical influences G an exploration of her key ideas on theater and the creative process G analysis of key productions, including her early and groundbreaking environmental political piece, 1789, and the later Asian-inspired play penned by Hélène Cixous, Drums on the Dam G practical exercises, including tips on mask work. As a first step toward critical understanding, and as an initial exploration before going on to further,primary research, Routledge Performance Practitioners are unbeatable value for today’s student. Judith G. Miller is Chair and Professor of French and Francophone Theatre in the Department of French at New York University. -

The Deep Blue Sea by Terence Rattigan

Director Sarah Esdaile Designer Ruari Murchison Lighting Designer Chris Davey Sound Designer Mic Pool Composer Simon Slater Casting Director Siobhan Bracke Voice Charmian Hoare Cast Ross Armstrong, Sam Cox, John Hollingworth, Maxine Peake, Ann Penfold John Ramm, Lex Shrapnel, Eleanor Wyld 18 February to 12 March By Terence Rattigan Teacher Resource Pack Introduction Welcome to the Resource Pack for West Yorkshire Playhouse’s production of The Deep Blue Sea by Terence Rattigan. In the pack you will find a host of information sheets to enhance your visit to the show and to aid your students’ exploration of this classic text. Contents: Page 2 Synopsis Pages 3 Terence Rattigan Timeline Page 5 The Rehearsal Process Page 10 Interview with Sarah Esdaile, Director and Maxine Peake, Hester Page 12 Interview with Suzi Cubbage, Production Manager Page 14 The Design The Deep Blue Sea By Terence Rattigan, Directed by Sarah Esdaile, Designed Ruari Murchison Hester left her husband for another man. Left the security of the well respected judge, for wild, unpredictable, sexy Freddie – an ex-fighter pilot. Now she’s reached the end of the line. Freddie’s raffish charm has worn thin and Hester is forced to face the reality of life with a man who doesn’t want to be with her. The simple act of a forgotten birthday pushes her to desperation point and to facing a future that offers no easy resolutions. Rattigan’s reputation was founded on his mastery of the ‘well made play’. Now, one hundred years after his birth, it is his skilful creation of troubled, emotional characters that has brought audiences and critics alike to re-visit his plays with renewed appreciation. -

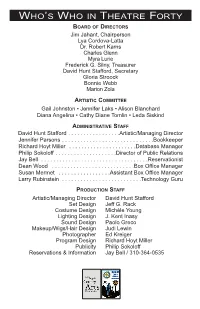

DIRECTED by JULES AARON PRODUCED by DAVID HUNT STAFFORD Set Designer

WHO’S WHO IN THEATRE FORTY BOARD OF DIRECTORS Jim Jahant, Chairperson Lya Cordova-Latta Dr. Robert Karns Charles Glenn Myra Lurie Frederick G. Silny, Treasurer David Hunt Stafford, Secretary Gloria Stroock Bonnie Webb Marion Zola ARTISTIC COMMITTEE Gail Johnston • Jennifer Laks • Alison Blanchard Diana Angelina • Cathy Diane Tomlin • Leda Siskind ADMINISTRATIVE STAFF David Hunt Stafford . .Artistic/Managing Director Jennifer Parsons . .Bookkeeper Richard Hoyt Miller . .Database Manager Philip Sokoloff . .Director of Public Relations Jay Bell . .Reservationist Dean Wood . .Box Office Manager Susan Mermet . .Assistant Box Office Manager Larry Rubinstein . .Technology Guru PRODUCTION STAFF Artistic/Managing Director David Hunt Stafford Set Design Jeff G. Rack Costume Design Michèle Young Lighting Design J. Kent Inasy Sound Design Paolo Greco Makeup/Wigs/Hair Desi gn Judi Lewin Photographer Ed Kreiger Program Design Richard Hoyt Miller Publicity Philip Sokoloff Reservations & Information Jay Bell / 310-364-0535 THEATRE FORTY PRESENTS The 6th Production of the 2016-2017 Season SeparateSeparate TablesTables BY TERENCE RATTIGAN DIRECTED BY JULES AARON PRODUCED BY DAVID HUNT STAFFORD Set Designer..............................................JEFF G. RACK Costume Designer................................MICHÈLE YOUNG Lighting Designer....................................J. KENT INASY Sound Designer ........................................PAOLO GRECO Makeup/Wigs/Hair Designer.....................JUDI LEWIN Stage Manager.........................................DON SOLOSAN Assistant Stage Manager ..................RICHARD CARNER Assistant Director.................................JORDAN HOXSIE PRODUCTION NOTES "Loneliness is a terrible thing, don't you agree." "Yes I do agree. A terrible thing." -- Separate Tables SPECIAL THANKS Theatre 40 would like to thank the BHUSD Board of Education and BH High School administration for their assistance and support in making Theatre 40’s season possible. Thanks to… HOWARD GOLDSTEIN LISA KORBATOV NOAH MARGO MEL SPITZ ISABEL HACKER DR. -

KIEPENHEUER-Katalog 2017

iepenheuer Bühnenvertrieb KATALOG 2017 GUSTAV KIEPENHEUER BÜHNENVERTRIEBS-GMBH Schweinfurthstraße 60, D-14195 Berlin (Dahlem) Telefon: 030-89 71 84 0 • Telefax: 030-823 39 11 [email protected] • www.kiepenheuer-medien.de Dieser Katalog enthält die Bühnenwerke der GUSTAV KIEPENHEUER BÜHNENVERTRIEBS- GMBH. Die Gustav Kiepenheuer Bühnenvertriebs-GmbH vertritt ferner im eigenen Namen oder im Subvertrieb den Non-Printmedien gegenüber Prosawerke, Hör- und Fernsehspiele sowie Filmdrehbücher von Herbert Asmodi Rasi Levinas Ilse Gräfin von Bredow Ulrich del Mestre Ferdinand Bruckner Simone Meyer Oliver Bukowski Benno Meyer-Wehlack Klaus Chatten Egon Monk Martina Döcker Alexander Pfeuffer Dina El-Nawab Anne Rabe Torsten Enders Kristo Šagor Kerstin Engel Bernd Sahling Oskar Maria Graf Anke Schenkluhn Günter Grass Silke Schwella Michael Haneke Anna Seghers Hugo Hartung Alexander Spoerl Kai Hensel Heinrich Spoerl Judith Herzberg Markus Stromiedel Peter Hirche George Tabori Hans-Joachim Hohberg Anne C. Voorhoeve Silvio Huonder Irena Vrkljan Claudia Kattanek Conny Walther Thorsten Klein Lida Winiewicz Victor Klemperer Christa Wolf Markus Köbeli Heinz Oskar Wuttig Simone Kollmorgen Matthias Zschokke Dirk Laucke u.a. sowie Werke des HERDER VERLAGES, Freiburg, des RAVENSBURGER BUCHVERLAGES OTTO MAIER, Ravensburg, des DEUTSCHEN TASCHENBUCHVERLAGES, München, und des Verlages KLAUS WAGENBACH, Berlin GUSTAV KIEPENHEUER Bühnenvertriebs-GmbH – Schweinfurth Str. 60 – 14195 Berlin Telefon: 030 / 89 71 84 0 – Fax: 030 / 823 39 11 – [email protected] www.kiepenheuer-medien.de WB = Klaus Wagenbach Verlag RB = Ravensburger Buchverlag Otto Maier GmbH U = Uraufführung DE = Deutschsprachige Erstaufführung Deutsche Erstaufführung E = Erstaufführung der Übersetzung/Bearbeitung D = Damenrolle(n) H = Herrenrolle(n) K = Kinderrolle(n) kl. R. = kleine Rolle(n) St. = Statist(en) Navigationshilfe A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P R S T U V W Y Z ACHARD, MARCEL JEAN DER TRÄUMER Deutsch von A. -

Proquest Dissertations

Performance Insights Site-specific theatre and performance with special reference to Deborah Warner, Peter Brook and Ariane Mnouchkine William Joseph McEvoy PhD. University College London September 2003 ProQuest Number: U642828 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest. ProQuest U642828 Published by ProQuest LLC(2016). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Abstract This thesis aims to develop a critical vocabulary for dealing with site-specific performances. It focuses on their association with dereliction and decay and assesses the implications of this. A central claim is that these performance modes are best understood in terms of their critical reception. I argue that site-specific performances redefine the language of criticism while profoundly questioning theatre’s cultural location. Even in the cases of site-specific performances that flagrantly negate traditional theatre forms, the theatre text and critical frameworks, these return in said performances as fragmented, spectral or unconscious. The thesis divides into two parts. Part 1 deals with the emergence of site- specific performance at the intersection of trends in art and theatre in the 1960s. -

Au Soleil Même La Nuit

Au Soleil même la nuit Un film de Eric Darmon et Catherine Vilpoux production : Agat Films & Cie coproduction : Théâtre du Soleil et la Sept Arte, avec le soutien du Centre national de la cinématographie, 1997 162', Couleur Générique image : Eric Darmon montage : Catherine Vilpoux assistée de Valérie Meffre, Stéphanie Langlois et Sylvie Renaud musique : Jean-Jacques Lemêtre chargées de production : Marie Balducchi et Isabelle Pailles assistante de production : Adeline Mouillet effets spéciaux : Emeline Le Mezo mixage : Philippe Escanetrabe montage son : Vincent Delorme et Chrystel Alepee "A travers le suivi des répétitions de Tartuffe par la troupe du Théâtre du Soleil, de la vie quotidienne de celle-ci, des ateliers de construction de décors, des réunions de travail et des divers registres d'intervention d'Ariane Mnouchkine dans son théâtre, ce film rend compte du sens même du théâtre pour l'un des plus grands metteurs en scène français." (présentation Arte) TARTUFFE de Molière par le Théâtre du Soleil Avec Mise en scène. Ariane Mnouchkine Dorine. Juliana Carneiro Da Cunha Elmire. Nirupama Nityanandan Mariane. Renata Ramos-Maza Valère. Martial Jacques Flippe et Pote. Valérie Crouzet et Marie-Paule Ramo-Guinard Damis. Hélène Cinque Cléante. Duccio Bellugi Vannuccini Mme Pernelle. Myriam Azencot Orgon. Brontis Jodorowsky Tartuffe . Shahrokh Meshkin Ghalam M. Loyal . Laurent Clauwaert L'Exempt. Nicolas Sotnikoff Laurent. Jocelyn Lagarrigue Décor. Guy-Claude François Masques. Erhard Stiefel Costumes. Nathalie Thomas, Marie-Hélène Bouvet et Annie Tran Lumières. Jean-Michel Bauer, Cécile Allegoedi, Carlos Obregon et Jacques Poirot Régie son. Rodrigo Bachler Klein Musique. Cheb Hasni 02 Présentation Ce film est exceptionnel à plus d'un titre. -

Violence Tragique Et Guerres Antiques Au Miroir Du Théâtre Et Du Cinéma E E (XVII -XXI Siècles)

N°6 |2017 Violence tragique et guerres antiques au miroir du théâtre et du cinéma e e (XVII -XXI siècles) sous la direction de Tiphaine Karsenti & Lucie Thévenet http://atlantide.univ-nantes.fr Université de Nantes Table des matières ~ Avant-propos Ŕ CHRISTIAN BIET & FIONA MACINTOSH .............................................. 3 Introduction Ŕ TIPHAINE KARSENTI & LUCIE THÉVENET ............................................ 5 Le théâtre grec : un modèle ambigu TIPHAINE KARSENTI................................................................................................. 10 Ancient Tragedy Violence in the French Translations of Greek Tragedies (1692-1785) GÉRALDINE PRÉVOT ................................................................................................ 21 The So-called “Vogue” for Outdoor Theatre around the Time of the First World War: Meanings and Political Ambiguities of the Reference to Greek Theatre La violence contemporaine en question CHARITINI TSIKOURA .............................................................................................. 32 Aeschylus‟ Persians to Denounce Modern Greek Politics CLAIRE LECHEVALIER .............................................................................................. 42 Ancient Drama and Contemporary Wars: the City Laid Waste? SOFIA FRADE ........................................................................................................... 50 War, Revolution and Drama: Staging Greek Tragedy in Contemporary Portugal Logiques de l‟analogie ESTELLE BAUDOU -

Proquest Dissertations

Contemporary directing approaches to the classical Athenian chorus: The blood of Atreus Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Grittner, Michael Curtis Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 25/09/2021 15:19:58 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/278695 INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. in the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overiaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographlcally In this copy. -

Lucia Bensasson 1968 and Collaborative Creation at the Théâtre Du Soleil

Lucia Bensasson 1968 and Collaborative Creation at the Théâtre du Soleil The Creation of the Théâtre du Soleil as a Co-operative When I joined the Théâtre du Soleil in January 1968 for its production of Shakespeare’s A Midsummer’s Night Dream, the company had already celebrated its fourth anniversary and staged several plays. It would be even more accurate to say that the group who would found the Théâtre du Soleil had met several years before in the context of theatre at university. After Ariane Mnouchkine had travelled for over a year in Asia, the group was reunited and in May 1964 established the Théâtre du Soleil. The group of nine wanted to set up a collaborative theatre company right from its inception, and after listening to several recommendations decided to create the company as a collaborative workers’ production, where the rights and duties of each member would be the same. They believed that this is what suited them best. Each of the nine founders paid their share of the annuity – which amounted to 900 francs (£119.86) – to subsidise the co- operative. They continued their activities during the day (as a salesperson, student, photographer, model maker, teacher, sports teacher, and so forth). Ariane Films, a French film company co-founded by Ariane’s father, provided the group with a small office on the Champs-Elysée, which remained the registered office for the Théâtre du Soleil until the company’s permanent relocation at the Cartoucherie. The Co-operative The associates did not receive any salary (their troupe had since increased from nine to thirteen). -

The Example of French Translation of Shakespeare1 Leanore Lieblein

FALL 1990 SI Translation and Mise-en-Scène: The Example of French Translation of Shakespeare1 Leanore Lieblein The 1982 meeting of the Société Française Shakespeare contained a round table discussion on translating Shakespeare's plays. In it Jean-Michel Déprats tried to suggest that, theoretically at least, there need not be a difference between the translation of a dramatic text destined to be read and one destined to be performed, since the potential for performance inscribed in Shakespeare's text must be preserved in the process of translation: Traduit-on différemment selon que Von destine une traduction à la lecture ou à la scène? En droit cette distinction nya pas lieu d'être. Une traduction impraticable sur une scène, régie par une poétique de récrit, méconnaît une dimension essentielle du texte shakespearien, tout entier tendu vers la représentation.2 But others took issue. According to Michel Grivelet: "La traduction pour la lecture et la traduction pour la scène sont deux choses différentes. La traduction pour le théâtre est immédiatement subordonnée à la conception de la mise en scène" And Jean-Pierre Villequin agreed: "Les traductions pour le théâtre vieillissent vite et mal. Chaque nouvelle mise en scène demande une nouvelle traduction." For theatre directors of Shakespeare, too, at least in the period beginning with Peter Brook's Timon d'Athènes in 1974, theatrical translations were felt to reflect the language and sensibility of a given moment of reception and thus to narrow the range of possibility implicit in the original: "Pour Peter Brook le projet même de travailler sur Shakespeare supposait comme prémice la mise à jour du texte, selon une équation stricte: sans nouveau texte, pas de nouvelle mise en scène."2 Interviews with directors led Leanore Lieblein is Associate Professor of English at McGill University, Montreal.