The Suit Maketh the Man: Masculinity and Social Class in Kingsman: the Secret Service (Vaughn, 2014)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

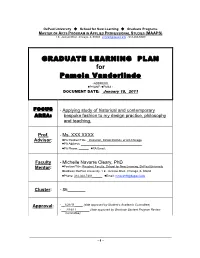

GRADUATE LEARNING PLAN for Pamela Vanderlinde

DePaul University School for New Learning Graduate Programs MASTER OF ARTS PROGRAM IN APPLIED PROFESSIONAL STUDIES (MAAPS) 1 E. Jackson Blvd., Chicago, IL 60604 [email protected] (312-362-8448) GRADUATE LEARNING PLAN for Pamela Vanderlinde •ADDRESS: •PHONE: •EMAIL: DOCUMENT DATE: January 18, 2011 FOCUS - Applying study of historical and contemporary AREA: bespoke fashion to my design practice, philosophy and teaching. Prof. - Ms. XXX XXXX Advisor: •PA Position/Title: _Instructor, Illinois Institute of Art-Chicago •PA Address: _____________________________________ •PA Phone: ______ •PA Email: Faculty - Michelle Navarre Cleary, PhD •Position/Title: Resident Faculty, School for New Learning, DePaul University Mentor: •Address: DePaul University, 1 E. Jackson Blvd., Chicago, IL 60604 •Phone: 312-362-7301______ •Email: [email protected] Cluster: - 86_______ - __1/21/11_____ (date approved by Student’s Academic Committee) Approval: - ___2/18/11________ (date approved by Graduate Student Program Review Committee) - 1 - PART I: Personal/Professional Background & Goals Directions: In Part I, the student provides a context for the Graduate Learning Plan and a rationale for both his/her career direction and choice of the MAAPS Program of study as a vehicle to assist movement in that direction. Specifically, Part I is to include three sections: A. a brief description of the student’s personal and professional history (including education, past/current positions, key interests, etc.); B. an explanation of the three or more years of experience (or equivalent) offered in support of the Graduate Focus Area; C. a brief description/explanation of the student’s personal and professional goals. A. Description of My Personal/Professional History: I have many passions in this world; fashion, teaching, travel, reading, yoga to name a few. -

The Secret Service - Kingsman Pdf, Epub, Ebook

THE SECRET SERVICE - KINGSMAN PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Mark Millar, Dave Gibbons | 160 pages | 24 Jan 2015 | Titan Books Ltd | 9781783293360 | English | London, United Kingdom The Secret Service - Kingsman PDF Book For assistance, contact your corporate administrator. Kingsman: The Secret Service. This site uses cookies. A spy organisation recruits a promising street kid into the agency's training program, while a global threat emerges from a twisted tech genius. Egerton does a capable job of keeping up with Firth, Caine and Jackson — no small feat. Bateman and Phillips worked closely to develop and source what would become both the on-screen costumes and eventual retail collection. After an entertaining but too-long series of sequences in which various candidates are weeded out, the real and really sick fun begins. Steve Persall. Bulls beat Rockets as veteran Otto Porter Jr. Harry is looking into the demise of another Kingsman, and the trail leads him to tech billionaire Valentine, a. By Tom Withers AP. A super-secret organization recruits an unrefined but promising street kid into the agency's ultra-competitive training program just as a dire global threat emerges from a twisted tech genius. Once you select Rent you'll have 14 days to start watching the movie and 24 hours to finish it. A phenomenal cast, including Colin Firth, Samuel L. Company Credits. Cookie banner We use cookies and other tracking technologies to improve your browsing experience on our site, show personalized content and targeted ads, analyze site traffic, and understand where our audiences come from. Harry may look and sound as though he spends more time at headquarters than in the field, but when a band of thugs tests his mettle in a British pub, Harry locks the doors, turns around, takes out his umbrella — and goon blood and goon teeth start flying. -

92Nd ACADEMY AWARDS® BALLOT

92nd ACADEMY AWARDS® BALLOT IMDb LIVE is covering the Academy Awards all evening long -- join us at IMDb.com on Feb. 9 at 7:30 p.m. ET/4:30 p.m. PT Name ¨ A B BEST ACHIEVEMENT ¨ A Marriage Story 8.1 14 Once Upon a Time... in Hollywood 7.7 Noah Baumbach IN COSTUME DESIGN Wylie Stateman A ¨ Once Upon a Time... in Hollywood 7.7 ¨ Jojo Rabbit A8.0 ¨ Star Wars: The Rise Of Skywalker A6.9 Total Correct Quentin Tarantino Mayes C. Rubeo Matthew Wood and David Acord A ¨ Parasite 8.6 ¨ Joker A8.6 /24 Bong Joon Ho and Jin Won Han Mark Bridges BEST ACHIEVEMENT 20 ¨ Little Women A8.1 IN VISUAL EFFECTS Jacqueline Durran BEST MOTION PICTURE BEST ADAPTED ¨ 1917 A8.5 01 08 A OF THE YEAR SCREENPLAY ¨ Once Upon a Time... in Hollywood 7.7 Guillaume Rocheron, Greg Butler, and A Arianne Phillips Dominic Tuohy ¨ 1917 A8.5 ¨ Jojo Rabbit 8.0 ¨ The Irishman A8.0 A Sam Mendes, Pippa Harris, Jayne-Ann Taika Waititi ¨ Avengers: Endgame 8.5 Christopher Peterson and Sandy Powell Tenggren, and Callum McDougall ¨ Joker A8.6 Dan DeLeeuw, Russell Earl, Matt Aitken, Todd Phillips and Scott Silver and Daniel Sudick ¨ Ford v Ferrari A8.2 A BEST ACHIEVEMENT IN ¨ A Peter Chernin, Jenno Topping, James Mangold ¨ Little Women 8.1 15 Star Wars: The Rise Of Skywalker 6.9 Greta Gerwig MAKEUP AND HAIRSTYLING Neal Scanlan, Patrick Tubach, Dominic Tuohy, ¨ Jojo Rabbit A8.0 and Roger Guyett Carthew Neal, Taika Waititi ¨ The Irishman A8.0 ¨ 1917 A8.5 Steven Zaillian ¨ The Irishman A8.0 ¨ Joker A8.6 Naomi Donne, Tristan Versluis, and Rebecca Cole Pablo Helman, Leandro Estebecorena, Todd Phillips, Bradley Cooper, Emma Tillinger ¨ The Two Popes A7.6 ¨ Bombshell A6.8 Nelson Sepulveda, and Stephane Grabli Koskoff Anthony McCarten Kazu Hiro, Anne Morgan, and Vivian Baker ¨ The Lion King A6.9 ¨ Little Women A8.1 ¨ Joker A8.6 Robert Legato, Adam Valdez, Andrew R. -

The Influence of Clothing on First Impressions: Rapid and Positive Responses

The influence of clothing on first impressions: Rapid and positive responses to minor changes in male attire Keywords: Clothing, first impressions, bespoke, influence, communication The influence of clothing on first impressions: Rapid and positive responses to minor changes in male attire. In a world that is becoming dominated by multimedia, the likelihood of people being judged on snapshots of their appearance is increasing. Social networking, dating websites and online profiles all feature people’s photographs, and subsequently convey a visual message to an audience. Whilst the salience of facial features is well documented, other factors, such as clothing, will also play a role in impression formation. Clothing can communicate an extensive and complex array of information about a person, without the observer having to meet or talk to the wearer. A person’s attire has been shown to convey qualities such as character, sociability, competence and intelligence (Damhorst, 1990), with first impressions being formed in a fraction of a second (Todorov, Pakrashi, and Oosterhof, 2009). This study empirically investigates how the manipulation of small details in clothing gives rise to different first impressions, even those formed very quickly. Damhorst (1990) states that ‘dress is a systematic means of transmission of information about the wearer’ (p. 1). A person’s choice of clothing can heavily influence the impression they transmit and is therefore a powerful communication tool. McCracken (1988) suggests that clothing carries cultural meaning and that this information is passed from the ‘culturally constructed world’ to clothing, through advertising and fashion. Clothes designers can, through branding and marketing, associate a new product or certain designs with an established cultural norm (McCracken, 1988). -

Sherlock Holmes

sunday monday tuesday wednesday thursday friday saturday KIDS MATINEE Sun 1:00! FEB 23 (7:00 & 9:00) FEB 24 & 25 (7:00 & 9:00) FEB 26 & 27 (3:00 & 7:00 & 9:15) KIDS MATINEE Sat 1:00! UP CLOUDY WITH A CHANCE OF MEATBALLS THE HURT LOCKER THE DAMNED PRECIOUS FEB 21 (3:00 & 7:00) Director: Kathryn Bigelow (USA, 2009, 131 mins; DVD, 14A) Based on the novel ‘Push’ by Sapphire FEB 22 (7:00 only) Cast: Jeremy Renner Anthony Mackie Brian Geraghty Ralph UNITED Director: Lee Daniels Fiennes Guy Pearce . (USA, 2009, 111 min; 14A) THE IMAGINARIUM OF “AN INSTANT CLASSIC!” –Wall Street Journal Director: Tom Hooper (UK, 2009, 98 min; PG) Cast: Michael Sheen, Cast: Gabourey Sidibe, Paula Patton, Mo’Nique, Mariah Timothy Spall, Colm Meaney, Jim Broadbent, Stephen Graham, Carey, Sherri Shepherd, and Lenny Kravitz “ENTERS THE PANTEHON and Peter McDonald DOCTOR PARNASSUS OF GREAT AMERICAN WAR BEST SUPPORTING ACTRESS MO’NIQUE FILMS!” –San Francisco “ONE OF THE BEST FILMS OF THE GENRE!” –Golden Globes, Screen Actors Guild Director: Terry Gilliam (UK/Canada/France, 2009, 123 min; PG) –San Francisco Chronicle Cast: Heath Ledger, Christopher Plummer, Tom Waits, Chronicle ####! The One of the most telling moments of this shockingly beautiful Lily Cole, Johnny Depp, Colin Farrell, and Jude Law Hurt Locker is about a bomb Can viewers who don’t know or care much about soccer be convinced film comes toward the end—the heroine glances at a mirror squad in present-day Iraq, to see Damned United? Those who give it a whirl will discover a and sees herself. -

Filmtemplate May2020 COMP

Our current favourite films Our recommended watch This feel-good, funny, escapist film from 1985 is exactly what we all need right now - whether we're watching it for the umpteenth or first Back To The Future time! The central character is Marty McFly, a 17 year old high school student, who accidentally travels thirty years into the past in a time- travelling DeLorean car, invented by his eccentric scientist friend Emmett "Doc" Brown. This is a wonderful classic for both adults and children. Action and Adventure Fantasy and Science Fiction Batman Avengers End Game Four Brothers Back to the Future Indiana Jones Blade Runner John Wick Guardians of the Galaxy True Romance Harry Potter Inception Lord of the Rings Crime and Suspense Planet of the Apes City of God X Men Godfather 2 Knives Out Limitless Historical - Drama Scarface Dead Poet’s Society The Accused Hidden Figures Trainspotting Madame x - Lana Turner The Blind Side (sport) The Favourite The Help Comedy - Romantic The King’s Speech 50 First dates The Lady in the Van About Time The Two Popes Amelie Gregory’s Girl Isn’t it Romantic Miss Congeniality Musical When Harry Met Sally A Star is Born (1976) Barbra Streisand (Classic) Beaches Chicago Dirty Dancing Classic) Comedy Grease Bad Boys 3 Kayote Ugly Saving Mr Banks Les Miserables The Green Book Mamma Mia The Kingsman Some like it Hot (Classic) West Side Story Yesterday Drama 10 Things I Hate About You Imagine Me & You Thrillers Shawshank redemption Shutter Island The Quiet American Silence of the Lambs Family Films Aladdin Beauty and the Beast (Musical) Chitty Chitty Bang Bang (musical) Christopher Robin Coco Django Home Alone Mary Poppins (Musical) Matilda (Musical) Oddball Paddington Secret Lives of Pets 2 The Lion King The Sound of Music (Musical) The Wizard of Oz (musical) Toy Story Up . -

Film Is GREAT, Edition 2, November 2016

©Blenheim Palace ©Blenheim Brought to you by A guide for international media The filming of James Bond’s Spectre, Blenheim Palace, Oxfordshire visitbritain.com/media Contents Film is GREAT …………………………………………………………........................................................................ 2 FILMED IN BRITAIN - British film through the decades ……………………………………………………………………………………….. 9 - Around the world in British film locations ……………………………………………….…………………........ 15 - Triple-take: Britain's busiest film locations …………………………………………………………………….... 18 - Places so beautiful you'd think they were CGI ……………………………………………………………….... 21 - Eight of the best: costume dramas shot in Britain ……………………………………………………….... 24 - Stay in a film set ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………...... 27 - Bollywood Britain …………………………………………………………………………………………………………….... 30 - King Arthur's Britain: locations of legend ……………………………………………………………………...... 33 - A galaxy far, far away: Star Wars in Britain .…………………………………………………………………..... 37 ICONIC BRITISH CHARACTERS - Be James Bond for the day …………………………………………………………………………………………….... 39 - Live the Bridget Jones lifestyle ……………………………………………………………………………………..... 42 - Reign like King Arthur (or be one of his knights) ………………………………………………………….... 44 - A muggles' guide to Harry Potter's Britain ……………………………………………………………………... 46 FAMILY-FRIENDLY - Eight of the best: family films shot in Britain ………………………………………………………………….. 48 - Family film and TV experiences …………………….………………………………………………………………….. 51 WATCHING FILM IN BRITAIN - Ten of the best: quirky -

1 Asdatown: the Intersections of Classed Places and Identities. Dr. B

Asdatown: The intersections of classed places and identities. Dr. B. Gidley and Dr. Alison Rooke Dept of Sociology Goldsmiths Introduction This chapter will explore the intersections between classed places and identities, focusing on the UK and examining the ways in which the figures of the ‘chav’ and the ‘pikey’ have been represented in British popular culture and in official policy discourses. We will argue that these representations conflate the racialized identity of the Gypsy Traveller with white working class identities and draw on the presence or proximity of Irish or Gypsy Travellers to the white ‘underclass’ in order to metonymically racialize the white working class as a whole. The politics of space, we will argue, is central to this process. Existing sociological and cultural geography literature hints at the active role of the spatial imaginary in classing people (Charleworth 2000, Robson 2000, Haylett 2000, Hewitt 2005, Skeggs 2005). We will argue that particular spaces and places – housing estates, and places described as ‘chav towns’ – are used discursively as a way of fixing people in racialized class positions. In British culture, there is a long history of reading poverty and class spatially. Indeed, the roots of British empirical sociology can be found in a middle class preoccupation with the poor working class others who could be located in districts of the city. While the persistence of poverty is explained in policy discourse in terms of ‘cycles’ and ‘cultures’ of poverty entrenched in a regressive or ‘backwards’ working 1 class, we will argue that what is regressive – and tainted by its Victorian imperialist history – is the persistent classing gaze which fixes working class people in place. -

Designing for the Plus-Size Men: Towards a Better Fitting: a Case of Harare, Zimbabwe

Journal of Textile Engineering & Fashion Technology Research Article Open Access Designing for the plus-size men: towards a better fitting: a case of Harare, Zimbabwe Abstract Volume 6 Issue 3 - 2020 This study endeavours to foster an understanding and encourage manufacturers to Denford Fadzai Chisosa, Verity Muzenda incorporate the plus sizes in their production to combat the fitting challenges connected to Department, of Clothing and Textile Technology, Chinhoyi plus-sized men in Harare. The plus sized men were facing challenges in finding some fitting University of Technology, Zimbabwe and ready- to-wear clothes on the market because of size restriction in a market. The clothing manufacturing companies was mass producing these ready-to-wear clothes ostensibly for Correspondence: Fadzai Denford Chisosa, Department, all men, ironically leaving the plus-sized men disgruntled due to misfitting clothes and of Clothing and Textile Technology, Chinhoyi University of size restrictions. The study used critical postmodernism and the concurrent triangulation Technology, P. Bag 7724 Chinhoyi, Zimbabwe, approaches to determine scope for either any convergence, differences or combination. Email Data was collected using questionnaires, interviews, observations and documentary analysis from the twenty-four (24) purposively sampled participants. Recommendations Received: May 28, 2020 | Published: June 24, 2020 were made for the clothing companies to integrate the extreme and in-between sizes. This study offers insights on better sizing for different body types eliminating the emotional psychology disturbances. Keywords: plus-size, clothing, ready- made, read-to wear Background fashionable, and non-favored bodies. In today’s extremely competitive clothing manufacturing business, Anthrotech (2002) posits that competitiveness increases when local clothing companies are faced with the dilemma of mass- clothes are customized, where more accurate clothes are made producing fast-selling clothes where size and fit are not a priority. -

The Aesthetics of Mainstream Androgyny

The Aesthetics of Mainstream Androgyny: A Feminist Analysis of a Fashion Trend Rosa Crepax Goldsmiths, University of London Thesis submitted for the degree of Ph.D. in Sociology May 2016 1 I confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Rosa Crepax Acknowledgements I would like to thank Bev Skeggs for making me fall in love with sociology as an undergraduate student, for supervising my MA dissertation and encouraging me to pursue a PhD. For her illuminating guidance over the years, her infectious enthusiasm and the constant inspiration. Beckie Coleman for her ongoing intellectual and moral support, all the suggestions, advice and the many invaluable insights. Nirmal Puwar, my upgrade examiner, for the helpful feedback. All the women who participated in my fieldwork for their time, patience and interest. Francesca Mazzucchi for joining me during my fieldwork and helping me shape my methodology. Silvia Pezzati for always providing me with sunshine. Laura Martinelli for always being there when I needed, and Martina Galli, Laura Satta and Miriam Barbato for their friendship, despite the distance. My family, and, in particular, my mum for the support and the unpaid editorial services. And finally, Goldsmiths and everyone I met there for creating an engaging and stimulating environment. Thank you. Abstract Since 2010, androgyny has entered the mainstream to become one of the most widespread trends in Western fashion. Contemporary androgynous fashion is generally regarded as giving a new positive visibility to alternative identities, and signalling their wider acceptance. But what is its significance for our understanding of gender relations and living configurations of gender and sexuality? And how does it affect ordinary people's relationship with style in everyday life? Combining feminist theory and an aesthetics that contrasts Kantian notions of beauty to bridge matters of ideology and affect, my research investigates the sociological implications of this phenomenon. -

Cineplex Store

Creative & Production Services, 100 Yonge St., 5th Floor, Toronto ON, M5C 2W1 File: AD Advice+ E 8x10.5 0920 Publication: Cineplex Mag Trim: 8” x 10.5” Deadline: September 2020 Bleed: 0.125” Safety: 7.5” x 10” Colours: CMYK In Market: September 2020 Notes: Designer: KB A simple conversation plus a tailored plan. Introducing Advice+ is an easier way to create a plan together that keeps you heading in the right direction. Talk to an Advisor about Advice+ today, only from Scotiabank. ® Registered trademark of The Bank of Nova Scotia. AD Advice+ E 8x10.5 0920.indd 1 2020-09-17 12:48 PM HOLIDAY 2020 CONTENTS VOLUME 21 #5 ↑ 2021 Movie Preview’s Ghostbusters: Afterlife COVER STORY 16 20 26 31 PLUS HOLIDAY SPECIAL GUY ALL THE 2021 MOVIE GIFT GUIDE We catch up with KING’S MEN PREVIEW Stressed about Canada’s most Writer-director Bring on 2021! It’s going 04 EDITOR’S Holiday gift-giving? lovable action star Matthew Vaughn and to be an epic year of NOTE Relax, whether you’re Ryan Reynolds to find star Ralph Fiennes moviegoing jam-packed shopping online or out how he’s spending tell us about making with 2020 holdovers 06 CLICK! in stores we’ve got his downtime. Hint: their action-packed and exciting new titles. you covered with an It includes spreading spy pic The King’s Man, Here we put the spotlight 12 SPOTLIGHT awesome collection of goodwill and talking a more dramatic on must-see pics like CANADA last-minute presents about next year’s prequel to the super- Top Gun: Maverick, sure to please action-comedy Free Guy fun Kingsman films F9, Black Widow -

Basque Soccer Madness a Dissertation Submitted in Partial

University of Nevada, Reno Sport, Nation, Gender: Basque Soccer Madness A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Basque Studies (Anthropology) by Mariann Vaczi Dr. Joseba Zulaika/Dissertation Advisor May, 2013 Copyright by Mariann Vaczi All Rights Reserved THE GRADUATE SCHOOL We recommend that the dissertation prepared under our supervision by Mariann Vaczi entitled Sport, Nation, Gender: Basque Soccer Madness be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Joseba Zulaika, Advisor Sandra Ott, Committee Member Pello Salaburu, Committee Member Robert Winzeler, Committee Member Eleanor Nevins, Graduate School Representative Marsha H. Read, Ph. D., Dean, Graduate School May, 2013 i Abstract A centenarian Basque soccer club, Athletic Club (Bilbao) is the ethnographic locus of this dissertation. From a center of the Industrial Revolution, a major European port of capitalism and the birthplace of Basque nationalism and political violence, Bilbao turned into a post-Fordist paradigm of globalization and gentrification. Beyond traditional axes of identification that create social divisions, what unites Basques in Bizkaia province is a soccer team with a philosophy unique in the world of professional sports: Athletic only recruits local Basque players. Playing local becomes an important source of subjectivization and collective identity in one of the best soccer leagues (Spanish) of the most globalized game of the world. This dissertation takes soccer for a cultural performance that reveals relevant anthropological and sociological information about Bilbao, the province of Bizkaia, and the Basques. Early in the twentieth century, soccer was established as the hegemonic sports culture in Spain and in the Basque Country; it has become a multi- billion business, and it serves as a powerful political apparatus and symbolic capital.