Bischoff and the Gascoigne House

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Surround/S—Poetry in Landscape Forms

JULY 2015 The Newsletter of Canberra Potters’ Society Inc. INSIDE: Surround/s Reviewed Soda Firing Report Juz Kitson Interview 40th Birthday Winter Fair Market Place...and more Greg Daly, Golden Light, 2014 Thrown, lustreglaze [silver] and brushwork, 140x430mm Image: the artist Surround/s—poetry Special Shorts Term 3 enrolements are open! Don’t miss out on our Special Shorts which in landscape forms include: Soft Slabs with Velda Hunter where you can explore working Review by Kathryn Wells with soft slabs to create quick, free flowing forms. A three day class over Curated by Patsy Hely and Sarah Rice The mountains surrounding Canberra two weekends Cooking With Gas where Chris Harford will skill you Watson Arts Centre are specifically referenced in many up on the gas kiln and includes a 2-26 July 2015, Opening 10 July 6 pm works: the leaves of Mount Majura pizza lunch on the last day. Finally Surround/s offers visitors the etched to highlight the tissue transfer join Cathy Franzi for an advanced opportunity to immerse themselves in on fine lustre porcelain by Patsy Payne, throwing class held over six Friday the poetry of landscape that defines the grassy box-gum woodlands of nights. Details on our website. the Canberra region. It is an exhibition Mount Ainslie and Red Hill with native that reveals a mastery with new grass Poa Labillaardieri growing in Great Prizes! forms and maturity of talent that has stoneware by Anne Langridge. Stepping Up fundraising raffle tickets the capacity to express this poetry Melinda Brouwer’s Border captures are available from CPS. -

Review Section

CSIRO PUBLISHING www.publish.csiro.au/journals/hras Historical Records of Australian Science, 2004, 15, 121–138 Review Section Compiled by Libby Robin Centre for Resource and Environmental Studies (CRES), Australian National University, Canberra, ACT, 0200, Australia. Email: [email protected] Tom Frame and Don Faulkner: Stromlo: loss of what he described as a ‘national an Australian observatory. Allen & Unwin: icon’. Sydney, 2003. xix + 363 pp., illus., ISBN 1 Institutional histories are often suffused 86508 659 2 (PB), $35. with a sense of inevitability. Looking back from the security of a firmly grounded present, the road seems straight and well marked. The journey that is reconstructed is one where the end point is always known, where uncertainties and diversions are forgotten — a journey that lands neatly on the institution’s front doorstep. Institu- tional histories are often burdened, too, by the expectation that they will not merely tell a story, but provide a record of achieve- ment. Written for the institution’s staff, as well as broader public, they can become bogged down in the details of personnel and projects. In this case, the fires of January 2003 add an unexpected final act Few institutional histories could boast such to what is a fairly traditional story of a dramatic conclusion as Stromlo: an Aus- growth and success. The force of nature tralian observatory. The manuscript was intervenes to remind us of the limits of substantially complete when a savage fire- inevitability, to fashion from the end point storm swept through the pine plantations another beginning. flanking Mount Stromlo, destroying all the The book is roughly divided into halves. -

Inquiry Into Nature in Our City

INQUIRY INTO NATURE IN OUR CITY S TANDING C OMMITTEE ON E NVIRONMENT AND T RANSPORT AND C ITY S ERVICES F EBRUARY 2020 REPORT 10 I NQUIRY INTO N ATURE IN O UR C ITY THE COMMITTEE COMMITTEE MEMBERSHIP CURRENT MEMBERS Ms Tara Cheyne MLA Chair (from 23 August 2019) Miss Candice Burch MLA Member (from 15 Feb 2018) and Deputy Chair (from 28 Feb 2018) Mr James Milligan MLA Member (from 20 September 2018) PREVIOUS MEMBERS Mr Steve Doszpot MLA Deputy Chair (until 25 November 2017) Mr Mark Parton MLA Member (until 15 February 2018) Ms Tara Cheyne MLA Member (until 20 September 2018) Ms Nicole Lawder MLA Member (15 February 2018 to 20 September 2018) Ms Suzanne Orr MLA Chair (until 23 August 2019) SECRETARIAT Danton Leary Committee Secretary (from June 2019) Annemieke Jongsma Committee Secretary (April 2019 to June 2019) Brianna McGill Committee Secretary (May 2018 to April 2019) Frieda Scott Senior Research Officer Alice Houghton Senior Research Officer Lydia Chung Administration Michelle Atkins Administration CONTACT INFORMATION Telephone 02 6205 0124 Facsimile 02 6205 0432 Post GPO Box 1020, CANBERRA ACT 2601 Email [email protected] Website www.parliament.act.gov.au i S TANDING C OMMITTEE ON E NVIRONMENT AND T RANSPORT AND C ITY S ERVICES RESOLUTION OF APPOINTMENT The Legislative Assembly for the ACT (the Assembly) agreed by resolution on 13 December 2016 to establish legislative and general purpose standing committees to inquire into and report on matters referred to them by the Assembly or matters that are considered by -

A Walk with Dr Allan Sandage—Changing the History of Galaxy Morphology, Forever

Lessons from the Local Group Kenneth Freeman • Bruce Elmegreen David Block • Matthew Woolway Editors Lessons from the Local Group A Conference in honour of David Block and Bruce Elmegreen 2123 Editors Kenneth Freeman David Block Australian National University University of the Witwatersrand Canberra Johannesburg Australia South Africa Bruce Elmegreen Matthew Woolway IBM T.J. Watson Research Center University of the Witwatersrand Yorktown Heights, New York Johannesburg United States South Africa Cover Photo: Set within 120 hectares of land with luxuriant and rare vegetation in the Seychelles Archipelago, the Constance Ephelia Hotel was selected as the venue for the Block-Elmegreen Conference held in May 2014. Seen in our cover photograph are one of the restaurants frequented by delegates - the Corossol Restaurant. The restaurant is surrounded by pools of tranquil waters; lamps blaze forth before dinner, and their reflections in the sur- rounding waters are breathtaking. The color blue is everywhere: from the azure blue skies above, to the waters below. Above the Corossol Restaurant is placed a schematic of a spiral galaxy. From macrocosm to microcosm. Never before has an astronomy group of this size met in the Seychelles. The cover montage was especially designed for the Conference, by the IT-Department at the Constance Ephelia Hotel. ISBN 978-3-319-10613-7 ISBN 978-3-319-10614-4 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-10614-4 Springer Cham Heidelberg New York Dordrecht London Library of Congress Control Number: 2014953222 © Springer International Publishing Switzerland 2015 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. -

Thesis Title

Creating a Scene: The Role of Artists’ Groups in the Development of Brisbane’s Art World 1940-1970 Judith Rhylle Hamilton Bachelor of Arts (Hons) University of Queensland Bachelor of Education (Arts and Crafts) Melbourne State College A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2014 School of English, Media Studies and Art History ii Abstract This study offers an analysis of Brisbane‘s art world through the lens of artists‘ groups operating in the city between 1940 and 1970. It argues that in the absence of more extensive or well-developed art institutions, artists‘ groups played a crucial role in the growth of Brisbane‘s art world. Rather than focusing on an examination of ideas about art or assuming the inherently ‗philistine‘ and ‗provincial‘ nature of Brisbane‘s art world, the thesis examines the nature of the city‘s main art institutions, including facilities for art education, the art market, conservation and collection of art, and writing about art. Compared to the larger Australian cities, these dimensions of the art world remained relatively underdeveloped in Brisbane, and it is in this context that groups such as the Royal Queensland Art Society, the Half Dozen Group of Artists, the Younger Artists‘ Group, Miya Studios, St Mary‘s Studio, and the Contemporary Art Society Queensland Branch provided critical forms of institutional support for artists. Brisbane‘s art world began to take shape in 1887 when the Queensland Art Society was founded, and in 1940, as the Royal Queensland Art Society, it was still providing guidance for a small art world struggling to define itself within the wider network of Australian art. -

Walks and Social Program

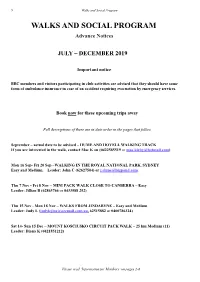

9 Walks and Social Program WALKS AND SOCIAL PROGRAM Advance Notices JULY – DECEMBER 2019 Important notice BBC members and visitors participating in club activities are advised that they should have some form of ambulance insurance in case of an accident requiring evacuation by emergency services. Book now for these upcoming trips away Full descriptions of these are in date order in the pages that follow September – actual date to be advised – HUME AND HOVELL WALKING TRACK If you are interested in the walk, contact Mac K on (0422585519 or [email protected]) Mon 16 Sep- Fri 20 Sep –WALKING IN THE ROYAL NATIONAL PARK, SYDNEY Easy and Medium. Leader: John C (62627504) or [email protected]. Thu 7 Nov - Fri 8 Nov – MINI PACK WALK CLOSE TO CANBERRA – Easy Leader: Jillian B (62863766 or 0433588 252) Thu 15 Nov - Mon 18 Nov – WALKS FROM JINDABYNE – Easy and Medium Leader: Judy L ([email protected], 62515882 or 0400786324) Sat 14- Sun 15 Dec – MOUNT KOSCIUSKO CIRCUIT PACK WALK – 25 km Medium (11) Leader: Diana K (0421851212) Please read ‘Information for Members’ on pages 2-8 10 Walks and Social Program Wed 3 Jul – SHORT WEDNESDAY WALK – Easy Contact: Robyn K (62880449) or Colleen F (62883153) or email [email protected] Wed 3 Jul – EASY/MEDIUM WEDNESDAY WALK (BBC) – Walks graded at the upper level of ‘Easy’ or the lower level of ‘Medium’. Leader: David W (62861573) Wed 3 Jul – MEDIUM/HARD WEDNESDAY WALK (BBC) – Medium to Hard graded walks. Leader: Peter D (0414363255) Sat 6 Jul – CENTENARY TRAIL– O’CONNOR TO ARBORETUM – 11 km Easy (7) Leader: Peter B (0413378684). -

Scientists' Houses in Canberra 1950–1970

EXPERIMENTS IN MODERN LIVING SCIENTISTS’ HOUSES IN CANBERRA 1950–1970 EXPERIMENTS IN MODERN LIVING SCIENTISTS’ HOUSES IN CANBERRA 1950–1970 MILTON CAMERON Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://epress.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: Cameron, Milton. Title: Experiments in modern living : scientists’ houses in Canberra, 1950 - 1970 / Milton Cameron. ISBN: 9781921862694 (pbk.) 9781921862700 (ebook) Notes: Includes bibliographical references and index. Subjects: Scientists--Homes and haunts--Australian Capital Territority--Canberra. Architecture, Modern Architecture--Australian Capital Territority--Canberra. Canberra (A.C.T.)--Buildings, structures, etc Dewey Number: 720.99471 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design by Sarah Evans. Front cover photograph of Fenner House by Ben Wrigley, 2012. Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2012 ANU E Press; revised August 2012 Contents Acknowledgments . vii Illustrations . xi Abbreviations . xv Introduction: Domestic Voyeurism . 1 1. Age of the Masters: Establishing a scientific and intellectual community in Canberra, 1946–1968 . 7 2 . Paradigm Shift: Boyd and the Fenner House . 43 3 . Promoting the New Paradigm: Seidler and the Zwar House . 77 4 . Form Follows Formula: Grounds, Boyd and the Philip House . 101 5 . Where Science Meets Art: Bischoff and the Gascoigne House . 131 6 . The Origins of Form: Grounds, Bischoff and the Frankel House . 161 Afterword: Before and After Science . -

European Influences in the Fine Arts: Melbourne 1940-1960

INTERSECTING CULTURES European Influences in the Fine Arts: Melbourne 1940-1960 Sheridan Palmer Bull Submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements of the degree ofDoctor ofPhilosophy December 2004 School of Art History, Cinema, Classics and Archaeology and The Australian Centre The University ofMelbourne Produced on acid-free paper. Abstract The development of modern European scholarship and art, more marked.in Austria and Germany, had produced by the early part of the twentieth century challenging innovations in art and the principles of art historical scholarship. Art history, in its quest to explicate the connections between art and mind, time and place, became a discipline that combined or connected various fields of enquiry to other historical moments. Hitler's accession to power in 1933 resulted in a major diaspora of Europeans, mostly German Jews, and one of the most critical dispersions of intellectuals ever recorded. Their relocation to many western countries, including Australia, resulted in major intellectual and cultural developments within those societies. By investigating selected case studies, this research illuminates the important contributions made by these individuals to the academic and cultural studies in Melbourne. Dr Ursula Hoff, a German art scholar, exiled from Hamburg, arrived in Melbourne via London in December 1939. After a brief period as a secretary at the Women's College at the University of Melbourne, she became the first qualified art historian to work within an Australian state gallery as well as one of the foundation lecturers at the School of Fine Arts at the University of Melbourne. While her legacy at the National Gallery of Victoria rests mostly on an internationally recognised Department of Prints and Drawings, her concern and dedication extended to the Gallery as a whole. -

The Old Sheep Camp on Mount Majura

The Old Sheep Camp on Mount Majura Research on the history of the site and a management plan for its rehabilitation. By William Mudford Venturer Scout at Majura Mountain Scouts Research assisted by Waltraud Pix Co-ordinator of Friends of Mount Majura Park Care Group William Mudford’s Queen Scout Environment Project on Mount Majura Sheep Camp: Page 1 Introduction Mount Majura is located in the North of the Australian Capital Territory. A majority of Mount Majura is currently run as a Nature Reserve. Many parts of the reserve have infestations of non- indigenous plants, or weeds, because of prior land use and farming practices. One particular site, at the top of the Casuarina trail, on the saddle between Mount Majura and Mount Ainslie, known as the “Old Sheep Camp” is particularly infested with weeds. In my project I investigated the history of the site, the reasons for the weed infestation and the methods of rehabilitation the local park care group have available to them, and are utilising. This project seeks to answer the following questions about the site: 1. Who owned and managed the area and how was it used before it became a Nature Reserve? 2. What are the reasons for the heavy weed infestation on the site? 3. What processes and procedures can the local environment group use to rehabilitate the area? William Mudford’s Queen Scout Environment Project on Mount Majura Sheep Camp: Page 2 Contents Part 1 – The history of the area Page 4 Part 2 – The reasons for the infestation of non-indigenous flora at the Sheep Camp site. -

Artists Statement for Me the Nature of Colour Is the Colour of Nature

David Aspden Born Bolton, England, arrived Australia 1950 1935 - 2005 COLLECTIONS Aspden is represented in National Gallery of Australia, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Art Gallery of Western Australia, Museums and Galleries of the Northern Territory, National Gallery of Victoria, Art Gallery of South Australia, and other state galleries. His work is found in regional galleries including Bathurst, Newcastle, Wollongong, Gold Coast, Orange, Armidale, Ballarat, Benalla, Muswellbrook, Manly, Stanthorpe and Geelong. Aspden’s paintings are hung in New Parliament House, Canberra and the NSW State Parliament. His work is in the collections of Artbank, Heide, Tarrawarra Museum of Art, Macquarie University, National Bank of Australia, Macquarie Bank, St George Bank, The Australian Club, Festival Hall Adelaide, Allens Arthur Robinson, Clayton Utz, Melbourne Casino, Fairfax, News Limited, University of Western Australia, Monash University, Beljourno Group, Shell Company of Australia Limited, and numerous corporate and private collections. Individual Exhibitions 1965 Watters Gallery, Sydney 1966 Watters Gallery, Sydney - March and November 1967 Watters Gallery, Sydney Strines Gallery, Melbourne 1968 Farmers' Blaxland Gallery, Sydney Gallery A, Melbourne 1970 Rudy Komon Art Gallery, Sydney 1971 Rudy Komon Art Gallery, Sydney 1973 Rudy Komon Art Gallery, Sydney 1974 Rudy Komon Art Gallery, Sydney 1975 Solander Gallery, Canberra 1976 Monash University, Victoria Rudy Komon Art Gallery, Sydney 1977 Rudy Komon Art Gallery, Sydney 1981 Rudy Komon Art Gallery, -

Fred Williams

FRED WILLIAMS Born: 1927, Melbourne, Australia Died: 1982 SELECTED EXHIBITIONS 1947 Figure And Portrait Exhibition, Victorian Artists Society, Melbourne 1951 Ian Armstrong, Fred Williams, Harry Rosengrave, Stanley Coe Galleries, Melbourne Australian Arts Association Exhibition, Royal Watercolour Society Gallery, London. 1952 Group Exhibition, Australian Artists' Association 1957 Fred Williams, Oil Painting And Gouache, Australian Galleries, Melbourne Fred Williams, Etchings, Gallery Of Contemporary Art, Melbourne 1958 Fred Williams, Landscapes, Australian Galleries, Melbourne Fred Williams - Etchings, Gallery Of Contemporary Art, Melbourne May Day Art Show, Lower Town Hall, Melbourne A Critic's Choice, Selected By Alan Mcculloch, Australian Galleries, Melbourne 2nd Anniversary Exhibition, Australian Galleries, Melbourne Crouch Prize, Ballarat Art Gallery, Victoria 1959 Fred Williams, Recent Landscapes And Still Life, Australian Galleries, Melbourne 18 Recent Acquisitions..., Museum Of Modern Art, Melbourne 1960 Fred Williams, Australian Galleries, Melbourne Helena Rubenstein Travelling Art Scholarship, (By Invitation), National Gallery Of Victoria, Melbourne Drawings And Prints, Australian Galleries, Melbourne 1960 Perth Art Prize, Art Gallery Society, Western Australia, Art Gallery Of W.A., Perth Mccaughey Memorial Art Prize, National Gallery Of Victoria, Melbourne Drawings, Paintings And Prints Up To 45 Gns, Australian Galleries, Melbourne 1961 Fred Williams, Paintings, Australian Galleries, Melbourne Fred Williams, The Bonython Art -

Attachment A

ATTACHMENT A Original Referral, October 2019 LIST OF ATTACHMENTS ATTACHMENT DESCRIPTION STATUS Submission, October 2019 Included A Action Area Location Plan Included B Action Area Site Plan and Disturbance Areas Included C Indigenous Consultation Summary (Redacted) Superseded by ATTACHMENT S of the Final Preliminary Documentation September 2020 Resubmission D Stakeholder Engagement and Consultation Report Superseded by ATTACHMENT S of the Final Preliminary Documentation September 2020 Resubmission E AWM Redevelopment HIA Superseded by ATTACHMENT D of the Final Preliminary Documentation September 2020 Resubmission F Mitigation Measures Included G ACT Standard Construction Environmental Management Plan Included H Energy and Environmental Policy, May 2019 Included I National Collection Environmental Management Plan Included (NCEMP) EPBC Act referral Note: PDF may contain fields not relevant to your application. These fields will appear blank or unticked. Please disregard these fields. Title of proposal 2019/8574 - Australian War Memorial Redevelopment Section 1 Summary of your proposed action 1.1 Project industry type Commonwealth 1.2 Provide a detailed description of the proposed action, including all proposed activities Overview The proposed action is the redevelopment of the Australian War Memorial (the Memorial), specifically the Southern Entrance, Parade Ground Anzac Hall and new glazed courtyard. The Project is being undertaken to address current constraints in available display space (including future provision) and visitor amenity, enabling the Memorial to fulfil its role of telling the story of Australian’s experience in conflicts, peacekeeping and humanitarian operations. The action proposed is consistent with the Project’s Detailed Business Case (DBC) as announced by the Commonwealth Government in November 2018 and funded in the Mid-Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook 2018-19 (Ref.