STAGES Also in This Issue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Joshua Anderson, CAS Production Sound Mixer

Joshua Anderson, CAS Production Sound Mixer Cinema Audio Society (CAS); I.A.T.S.E., local 695 (Los Angeles); I.A.T.S.E., local 52 (New York) Cell: 347.512.2157 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.productionsoundmixer.com IMDb: www.imdb.com/name/nm1220095 Television (Selected List) THE ORVILLE (Season 3) 20th Century Fox, Hulu (2021) Line Producer: Howard Griffith; UPM: Lillian Awa Cast: Seth MacFarlane, Adrianne Palicki, Penny Johnson Jerald, Scott Grimes WU-TANG: AN AMERICAN SAGA (Season 1) Imagine Television, Hulu (2019) Line Producer: Gail Barringer, Robert Ortiz; UPM: Ernesto Alcalde, Alyson Latz Cast: Ashton Sanders, Shameik Moore, Erika Alexander, Dave East, Siddiq Saunderson JESSICA JONES (Seasons 1, 2 & 3) ABC Studios, Marvel TV, Netflix (2015, 2018 & 2019) Line Producer: Tim Iacofano; UPM: Evan Perazzo, Jonathan Shoemaker Cast: Krysten Ritter, Carrie-Ann Moss, David Tenant, Janet McTeer, Rachel Taylor DAREDEVIL (Seasons 1 & 3) ABC Studios, Marvel TV, Netflix (2015 & 2018) Line Producer: Kati Johnston, Evan Perazzo; UPM: Jill Footlick, Jonathan Shoemaker Cast: Charlie Cox, Vincent D’Onofrio, Rosario Dawson, Elden Hensen, Deborah Ann Woll THE DEFENDERS (Mini Series) ABC Studios, Marvel TV, Netflix (2017) Line Producer: Evan Perazzo; UPM: Holly Rymon Cast: Charlie Cox, Krysten Ritter, Mike Colter, Finn Jones, Sigourney Weaver IRON FIST (Season 1) ABC Studios, Marvel TV, Netflix (2017) Line Producer: Evan Perazzo; UPM: Tyson Bidner, Holly Rymon Cast: Finn Jones, David Wenham, Jessica Henwick, Tom Pelfry, Rosario Dawson -

'COMEDY CENTRAL's Hot List' Debuting Sunday, December 5 at 10:00 P.M.*

What Winter Cold? These Comedians are Bringing the Heat! Check Out the World Premiere of 'COMEDY CENTRAL's Hot List' Debuting Sunday, December 5 at 10:00 p.m.* NEW YORK, Nov. 16, 2010 /PRNewswire via COMTEX/ -- COMEDY CENTRAL is unleashing a new "Hot List" of its star comics upon the world! See who makes the cut in the World Premiere of "COMEDY CENTRAL's Hot List," debuting Sunday, December 5 at 10:00 p.m. With the success of 2009's "Hot List," which included white-hot comedians Aziz Ansari, Donald Glover, Nick Kroll and Whitney Cummings, COMEDY CENTRAL is proving its prophetic prowess yet again by rolling out a bevy of break-through talent that audiences will soon have to reckon with. COMEDY CENTRAL has picked seven of the hottest comedians who have been on a hot streak in the clubs, on the Internet, in films and on television. This year's cream of the comedic crop includes Pete Holmes ("John Oliver's New York Stand-Up Show," "COMEDY CENTRAL Presents"), Reggie Watts ("Michael & Michael Have Issues"), Chelsea Peretti ("COMEDY CENTRAL Presents," "The Sarah Silverman Program"), Kurt Metzger ("Ugly Americans," "COMEDY CENTRAL Presents"), Kyle Kinane ("COMEDY CENTRAL Presents," "Last Call with Carson Daly"), Natasha Leggero ("COMEDY CENTRAL Presents," "Ugly Americans," "Last Comic Standing") and Owen Benjamin ("The House Bunny," "COMEDY CENTRAL Presents"). "COMEDY CENTRAL's Hot List" includes interviews with the comedians as well as clips from their various performances and day-in-the-life footage captured with a self-recorded flipcam. Tune in Sunday, December 5 at 10:00 p.m. -

Following Is a List of All 2019 Festival Jurors and Their Respective Categories

Following is a list of all 2019 Festival jurors and their respective categories: Feature Film Competition Categories The jurors for the 2019 U.S. Narrative Feature Competition section are: Jonathan Ames – Jonathan Ames is the author of nine books and the creator of two television shows, Bored to Death and Blunt Talk His novella, You Were Never Really Here, was recently adapted as a film, directed by Lynne Ramsay and starring Joaquin Phoenix. Cory Hardrict– Cory Hardrict has an impressive film career spanning over 10 years. He currently stars on the series The Oath for Crackle and will next be seen in the film The Outpostwith Scott Eastwood. He will star and produce the film. Dana Harris – Dana Harris is the editor-in-chief of IndieWire. Jenny Lumet – Jenny Lumet is the author of Rachel Getting Married for which she received the 2008 New York Film Critics Circle Award, 2008 Toronto Film Critics Association Award, and 2008 Washington D.C. Film Critics Association Award and NAACP Image Award. The jurors for the 2019 International Narrative Feature Competition section are: Angela Bassett – Actress (What’s Love Got to Do With It, Black Panther), director (Whitney,American Horror Story), executive producer (9-1-1 and Otherhood). Famke Janssen – Famke Janssen is an award-winning Dutch actress, director, screenwriter, and former fashion model, internationally known for her successful career in both feature films and on television. Baltasar Kormákur – Baltasar Kormákur is an Icelandic director and producer. His 2012 filmThe Deep was selected as the Icelandic entry for the Best Foreign Language Oscar at the 85th Academy Awards. -

Medical School Basic Science Clinical Other Total Albany Medical

Table 2: U.S. Medical School Faculty by Medical School and Department Type, 2020 The table below displays the number of full-time faculty at all U.S. medical schools as of December 31, 2020 by medical school and department type. Medical School Basic Science Clinical Other Total Albany Medical College 74 879 48 1,001 Albert Einstein College of Medicine 316 1,895 21 2,232 Baylor College of Medicine 389 3,643 35 4,067 Boston University School of Medicine 159 1,120 0 1,279 Brody School of Medicine at East Carolina University 92 349 0 441 CUNY School of Medicine 51 8 0 59 California Northstate University College of Medicine 5 13 0 18 California University of Science and Medicine-School of Medicine 26 299 0 325 Carle Illinois College of Medicine 133 252 0 385 Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine 416 2,409 0 2,825 Central Michigan University College of Medicine 21 59 0 80 Charles E. Schmidt College of Medicine at Florida Atlantic University 30 64 0 94 Chicago Medical School at Rosalind Franklin University of Medicine & Science 69 25 0 94 Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons 282 1,972 0 2,254 Cooper Medical School of Rowan University 78 608 0 686 Creighton University School of Medicine 52 263 13 328 Donald and Barbara Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell 88 2,560 9 2,657 Drexel University College of Medicine 98 384 0 482 Duke University School of Medicine 297 998 1 1,296 East Tennessee State University James H. -

Liberty City Guidebook

Liberty City Guidebook YOUR GUIDE TO: PLACES ENTERTAINMENT RESTAURANTS TABLE OF CONTENTS A very small percentage of individuals may experience epileptic seizures or blackouts when exposed to certain light patterns or flashing lights. Exposure to certain patterns or backgrounds on a television screen or when playing video games may trigger epileptic seizures or blackouts in these individuals. These conditions may trigger previously undetected epileptic symptoms or seizures in persons who have no history of prior seizures or epilepsy. If you, or anyone in your family, has an epileptic condition or has had seizures of any kind, consult your physician before playing. IMMEDIATELY DISCONTINUE use and consult your physician before resuming gameplay if you or your child experience any of the following health problems or symptoms: • dizziness • eye or muscle twitches • disorientation • any involuntary movement • altered vision • loss of awareness • seizures or convulsion. RESUME GAMEPLAY ONLY ON APPROVAL OF YOUR PHYSICIAN. _____________________________________________________________________________________________ Use and handling of video games to reduce the likelihood of a seizure • Use in a well-lit area and keep as far away as possible from the television screen. • Avoid large screen televisions. Use the smallest television screen available. • Avoid prolonged use of the PLAYSTATION®3 system. Take a 15-minute break during each hour of play. • Avoid playing when you are tired or need sleep. _____________________________________________________________________________________________ Stop using the system immediately if you experience any of the following symptoms: lightheadedness, nausea, or a sensation similar to motion sickness; discomfort or pain in the eyes, ears, hands, arms, or any other part of the body. If the condition persists, consult a doctor. -

MD Class of 2021 Commencement Program

Commencement2021 Sunday, the Second of May Two Thousand Twenty-One Mount Airy Casino Resort Mt. Pocono, Pennsylvania Geisinger Commonwealth School of Medicine celebrates the conferring of Doctor of Medicine degrees For the live-stream event recording and other commencement information, visit geisinger.edu/commencement. Commencement 2021 1 A message from the president and dean Today we confer Doctor of Medicine degrees upon our our past, but we are not afraid to evolve and embrace ninth class. Every year at commencement, I like to reflect innovation, change and our future. To me, this courage, on the ways in which each class is unique. The Class resilience and creative thinking have come to be of 2021 presents an interesting duality. It is the first of synonymous with a Geisinger Commonwealth School some things and also the last of many. Like the Roman of Medicine diploma — and I have received enough god Janus, this class is one that looks back on our past, feedback from fellow physicians, residency program but also forward to the future we envision for Geisinger directors and community members to know others Commonwealth School of Medicine. believe this, too. Every student who crosses the stage Janus was the god of doors and gates, of transitions today, through considerable personal effort, has earned and of beginnings and ends. It is an apt metaphor, the right to claim the privileges inherent in because in so many ways yours has been a transitional that diploma. class. You are the last class to be photographed on Best wishes, Class of 2021. I know that the experiences, the day of your White Coat Ceremony wearing jackets growth and knowledge bound up in your piece of emblazoned “TCMC.” You are also, however, the first parchment will serve you well and make us proud in the class offered the opportunity of admittance to the Abigail years to come. -

The-Vandal.Pdf

THE FLEA THEATER JIM SIMPSON artistic director CAROL OSTROW producing director BETH DEMBROW managing director presents the world premiere of THE VANDAL written by HAMISH LINKLATER directed by JIM SIMPSON DAVID M. BARBER set design BRIAN ALDOUS lighting design CLAUDIA BROWN costume design BRANDON WOLCOTT sound design and original music MICHELLE KELLEHER stage manager EDWARD HERMAN assistant stage manager CAST (IN ALPHABETICAL ORDER) Man...........................................................................................................................Zach Grenier Woman...............................................................................................................Deirdre O’Connell Boy...........................................................................................................................Noah Robbins CREATIVE TEAM Playwright...........................................................................................................Hamish Linklater Director.......................................................................................................................Jim Simpson Set Design..............................................................................................................David M. Barber Lighting Design.........................................................................................................Brian Aldous Costume Design......................................................................................................Claudia Brown Sound Design and Original -

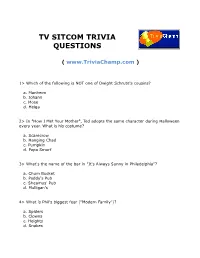

Tv Sitcom Trivia Questions

TV SITCOM TRIVIA QUESTIONS ( www.TriviaChamp.com ) 1> Which of the following is NOT one of Dwight Schrute's cousins? a. Manheim b. Johann c. Mose d. Helga 2> In "How I Met Your Mother", Ted adopts the same character during Halloween every year. What is his costume? a. Scarecrow b. Hanging Chad c. Pumpkin d. Papa Smurf 3> What's the name of the bar in "It's Always Sunny in Philadelphia"? a. Chum Bucket b. Paddy's Pub c. Sheamus' Pub d. Mulligan's 4> What is Phil's biggest fear ("Modern Family")? a. Spiders b. Clowns c. Heights d. Snakes 5> Who recorded the main music theme for "The Big Bang Theory"? a. Lazlo Bane b. They Might Be Giants c. The Barenaked Ladies d. Yukon Kornelius 6> Who is the main star of "Life's Too Short"? a. Steve Carell b. Ricky Gervais c. Warwick Davis d. Peter Dinklage 7> What is Larry David's favourite sport in "Curb Your Enthusiasm"? a. Chess b. Tennis c. Golf d. Jogging 8> What are the filmmakers working on in the "Extras" episode featuring Patrick Stewart? a. A sci-fi blockbuster b. Shakespeare's play c. Documentary with David Attenborough d. An epic historical movie 9> How much did Earl Hickey win in a lottery? a. $40000 b. $100000 c. $10000 d. $200000 10> Who plays Liz's ex-roommate in "30 Rock"? a. Jennifer Aniston b. Lisa Kudrov c. Salma Hayek d. Jaime Pressly 11> Where was Leslie Knope born ("Parks and Recreation")? a. Scranton b. Pawnee c. -

MTV Revisited After 20 Years

The Bronx Journal/September 2001 E N T E RTA I N M E N T A 11 MTV Revisited after 20 Years VIRGINIA ROHAN a description of the network’s influence that They seemed to wait for Europe to experi- still holds true: ence success with its “Real World” imita- or better or worse, the television “MTV has changed the video language,” tors before jumping into the reality fray. landscape in 2001 owes much of its said Herzog, who’s now president of USA The producers of “Big Brother” and its look and feel to MTV -- which cel- Network. current sequel may insist that it’s based on ebrates its 20th birthday this week, though “Whether it’s a movie or a TV show or an a Dutch show of the same name that has it's still a long way from acting like a stodgy advertisement, there’s a new way of telling conquered Europe, but the original inspira- TV grownup. stories, a new way of communicating that I tion was surely “Real World.” Hard to believe, but it's been two decades think has really evolved. Things are defi- The challenges of “Survivor” and shows since the birth of the cable network, offi- nitely happening faster, and [MTVis] clear- like “The Mole” and “Fear Factor” also cially known as Music Television. The his- ly part of that evolution.” clearly owe a debt to “Road Rules,” MTV’s toric first cablecast, on Aug. 1, 1981, actu- MTV has also introduced a number of “docu-adventure series,” which debuted in ally had a North Jersey connection: The television and movie personalities to July 1995. -

THIS ISSUE: Comedy

2014-2015 September ISSUE 1 scene. THE JOURNAL OF THE INTERNATIONAL SCHOOLS THEATRE ASSOCIATION THIS ISSUE: Comedy www.ista.co.uk WHO’S WHO @ ISTA… CONTENTS Patron 2 Connections Professor Jonothan Neelands, by Rebecca Kohler National Teaching Fellow, Chair of Drama and Theatre Education in the Institute of Education 3 Comedy d’un jour and Chair of Creative Education in the Warwick Business School (WBS) at the University of by Francois Zanini Warwick. 4 Learning through humour Board of trustees by Mike Pasternak Iain Stirling (chair), Scotland Formerly Superintendent, Advanced Learning Schools, Riyadh. Recently retired. 8 Desperately seeking the laughs Jen Tickle (vice chair), Jamaica by Peter Michael Marino Head of Visual & Performing Arts and Theory of Knowledge at The Hillel Academy, Jamaica. 9 “Chou” – the comic actor in Chinese opera Dinos Aristidou, UK by Chris Ng Freelance writer, director, consultant. 11 Directing comedy Alan Hayes, Belgium by Sacha Kyle Theatre teacher International School Brussels. Sherri Sutton, Switzerland 12 Videotape everything, change and be Comic, director and chief examiner for IB DP Theatre. Theatre teacher at La Chataigneraie. grateful Jess Thorpe, Scotland by Dorothy Bishop Co Artistic Director of Glas(s) Performance and award winning young people’s company 13 Seriously funny Junction 25. Visiting. Lecturer in the Arts in Social Justice at the Royal Conservatoire of Scotland. by Stephen Finegold Honorary life members 15 How I got the best job in the world! Dinos Aristidou, UK Being a clown, being a -

Life Episode Guide Episodes 001–032

Life Episode Guide Episodes 001–032 Last episode aired Wednesday April 8, 2009 www.nbc.com c c 2009 www.tv.com c 2009 www.nbc.com The summaries and recaps of all the Life episodes were downloaded from http://www.tv.com and processed through a perl program to transform them in a LATEX file, for pretty printing. So, do not blame me for errors in the text ^¨ This booklet was LATEXed on December 31, 2011 by footstep11 with create_eps_guide v0.31 Contents Season 1 1 1 Merit Badge . .3 2 Tear Asunder . .7 3 Let Her Go . .9 4 What They Saw . 11 5 The Fallen Woman . 13 6 Powerless . 15 7 A Civil War . 17 8 Farthingale . 19 9 Serious Control Issues . 21 10 Dig a Hole . 23 11 Fill It Up . 25 Season 2 27 1 Find Your Happy Place . 29 2 Everything... All the Time . 31 3 The Business of Miracles . 35 4 Not For Nothing . 39 5 Crushed . 43 6 Did You Feel That? . 47 7 Jackpot . 51 8 Black Friday . 55 9 Badge Bunny . 59 10 Evil...and his brother Ziggy . 63 11 Canyon Flowers . 67 12 Trapdoor . 71 13 Re-Entry . 75 14 Mirror Ball . 79 15 I Heart Mom . 81 16 Hit Me Baby . 85 17 Shelf Life . 89 18 3Women ............................................ 93 19 5 Quarts . 97 20 Initiative 38 . 101 21 One ............................................... 105 Actor Appearances 109 Life Episode Guide II Season One Life Episode Guide Merit Badge Season 1 Episode Number: 1 Season Episode: 1 Originally aired: Wednesday September 26, 2007 on NBC Writer: Rand Ravich Director: David Semel Show Stars: Damian Lewis (Charlie Crews), Brooke Langton (Constance), Brent Sexton (Bobby Starks), Adam Arkin (Ted Early), Sarah Shahi (Dani Reese), Robin Weigert (Lt. -

HOLOPAW Your Pathway to FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY

NAME 2016 STUDENT ORIENTATION HOLOPAW Your Pathway to FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY dos.fsu.edu/newnole ORIENTATION CHECKLIST Get your FSUCard Attend all of your orientation sessions Check your financial aid application status Purchase your dining membership Check on your housing application status Take a tour of campus Verify receipt of Immunization/Health Records at University Health Services Verify compliance with the Mandatory Health Insurance Policy 1 WELCOME Dear Seminoles, Welcome to Orientation at Florida State University! We are very excited that you are here and look forward to spending this time with you. Orientation is designed to help students prepare for college and to assist family members in understanding their student’s transition. Over a two day period, you will be attending presentations and programs that have been specifically designed for students and families. The Holopaw, a Creek Indian word meaning “pathways”, is your guide to campus while at orientation and beyond. We believe that orientation will serve as the first step in your journey toward becoming part of the rich heritage that is Florida State University. In the following pages you will find your orientation schedule.Some of the programs are together with your family and guests, while others are not. We ask that you only attend sessions that are on your schedule. You will be given the same information throughout orientation and have plenty of time to speak with each other. Please remember that students are required to attend all of their orientation programs before they will be cleared for course registration and attendance will be carefully taken during sessions.