Proquest Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Percussionist's Guide to Check Patterns Section Leader Program

350.00 The Mobile Percussion Seminar is designed to develop the A Percussionist’s Guide Tuition Only Balance Due COMMUTER mental and physical aspects of percussion performance and to Check Patterns leadership skills. Students will have a chance to work with Thom Hannum and his staff of specialists in the areas of From beginner to advanced marching percussion and mallet percussion. (PLEASE CHECK ONE) skill levels, Thom’s new book A Percussionist’s Guide to Thom Hannum, a Drum Corps International Hall of Fame Check Patterns, is designed member, is the Associate Band Director for the University of to help percussionists at Fee includes tee shirt and sticks / mallets Amount Enclosed Massachusetts Amherst Minuteman Marching Band and 550.00 any level perfect their craft. Sign up for our expanded SECTION LEADER TRACK Director of the Marimba Ensembles program. Thom is a RESIDENT worldv renowned percussion clinician and teacher and has Written for non-pitched percussion, Tuition/Room/Meals worked with the Cadets, the Star of Indiana and the Tony keyboard and drumset, the book provides a Award winning production Blast! Thom is currently the systematic approach to sticking rhythm patterns - ideal percussion arranger for Carolina Crown. for developing reading skills, coordination and syncopation control. The book is accompanied by a CD for rehearsal Features of the Seminar and individual practice and also includes a Vic Firth Check Patterns poster. M F • All battery percussion students will be assigned to a Students will work from both A Percussionist’s Guide to Sex group of their ability level Check Patterns and Thom’s other book, Championship ZIP ZIP • The Seminar offers a Leadership Training Track, Concepts for Marching Percussion, throughout the Seminar. -

Allan Goodwin CV

ALLAN F. GOODWIN Texas A&M University-Commerce Music Building 191 PO Box 3011 Commerce, TX 75429-3011 [email protected] (214) 529-5077 EDUCATION Master of Music Education (Conducting Emphasis) Tulsa, OK University of Tulsa – Henry Kendall College of Arts & Sciences School of Music 1997 Bachelor of Music (Music Education) Denton, TX University of North Texas – College of Music 1993 TEACHING EXPERIENCE Associate Director of Bands 2012 – Present Texas A&M University-Commerce (Commerce, TX) • Principal Conductor of the Symphonic Band o Ensemble consists of undergraduate and graduate music majors o Ensemble performs 3-4 times per year, headlining concerts with Concert Band o Recordings available upon request o Full listing of concert programs/repertoire available upon request • Principal Guest Conductor of the Concert Band o Ensemble consists of primarily undergraduate music majors o Coordinate literature selection with graduate conductors • Principal Guest Conductor of the Wind Ensemble o Notable recent guest conducting performances: • Texas Music Educators Association – Ira Hearshen Danish Bouquets (2013) • Chamber Ensemble Showcase – Michael Kamen Dectet (2016) • Mozarteum in Salzburg, Austria – Aaron Copland Old American Songs (2016) • Texas Music Educators Association – Petrov Trumpet Concerto (2018) • Participate in all recruiting activities for the Instrumental Division • Instruct Undergraduate Courses in Conducting, Secondary Music Education, Marching Band Techniques and Music Technology o MUS 310 – Music Education Technology -

Julia Gaines

JULIA GAINES EMPLOYMENT 1996 - University of Missouri School of Music Director – Fall 2014 Full Professor, Fall 2016 Associate Professor of Percussion – Fall 2010 Assistant Professor of Percussion – Fall 2002 Visiting/Resident Instructor of Percussion – Fall 1996 1996-1998 Central Methodist College Adjunct Percussion Instructor EDUCATION 1993-1999 UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA Doctor of Musical Arts in Performance Written Document Title: A Profile of the Perception of Instrumental Ensemble Directors in the States of Illinois, Missouri, and Wisconsin Regarding the Percussion Techniques Class Primary Instructor: Dr. Richard Gipson 1991-1993 EASTMAN SCHOOL OF MUSIC Master of Music in Performance and Literature Recipient of Performer’s Certificate Primary Instructor: John Beck 1987-1991 LAWRENCE CONSERVATORY OF MUSIC Bachelor of Music Performance, cum laude Primary Instructor: Dane Richeson Additional Instructors Mary Wells, Freelance Percussionist, Moscow, Idaho, 1980-1986 Dan Bukvich, University of Idaho, 1986-1987 Erik Forrester, Interlochen National Music Camp, 1986 Ralph Hardimon, Santa Clara Vanguard Drum Corps, 1989 Julia Gaines pg. 2 ADMINISTRATION Administration, 2014-present FUNDRAISING – over $23M $10 million building – 1 gift (2015) $2.1 and 2.4 M in programmatic composition-related funding – two gifts (2016, 2019) $6 million in additional building funding, many sources (2015-2019) $4 million estate gift – Center for American Music Studies (2019) $500,000 estate gift for Marching Mizzou (2019) $400,000 corporate sponsorships (MU Healthcare) for Marching Mizzou (2018) $70K annually Friends of Music LEADERSHIP DEVELOPMENT GMLC – 2018 participant, 2019 Board of Directors The Greater Missouri Leadership Challenge is an organization devoted to leadership development in Missouri. The Foundation arm of this group supports a year-long “challenge” for 40 women to visit four areas of Missouri to learn about all facets of the state. -

PASIC 2010 Program

201 PASIC November 10–13 • Indianapolis, IN PROGRAM PAS President’s Welcome 4 Special Thanks 6 Area Map and Restaurant Guide 8 Convention Center Map 10 Exhibitors by Name 12 Exhibit Hall Map 13 Exhibitors by Category 14 Exhibitor Company Descriptions 18 Artist Sponsors 34 Wednesday, November 10 Schedule of Events 42 Thursday, November 11 Schedule of Events 44 Friday, November 12 Schedule of Events 48 Saturday, November 13 Schedule of Events 52 Artists and Clinicians Bios 56 History of the Percussive Arts Society 90 PAS 2010 Awards 94 PASIC 2010 Advertisers 96 PAS President’s Welcome elcome 2010). On Friday (November 12, 2010) at Ten Drum Art Percussion Group from Wback to 1 P.M., Richard Cooke will lead a presen- Taiwan. This short presentation cer- Indianapolis tation on the acquisition and restora- emony provides us with an opportu- and our 35th tion of “Old Granddad,” Lou Harrison’s nity to honor and appreciate the hard Percussive unique gamelan that will include a short working people in our Society. Arts Society performance of this remarkable instru- This year’s PAS Hall of Fame recipi- International ment now on display in the plaza. Then, ents, Stanley Leonard, Walter Rosen- Convention! on Saturday (November 13, 2010) at berger and Jack DeJohnette will be We can now 1 P.M., PAS Historian James Strain will inducted on Friday evening at our Hall call Indy our home as we have dig into the PAS instrument collection of Fame Celebration. How exciting to settled nicely into our museum, office and showcase several rare and special add these great musicians to our very and convention space. -

Faculty Biographies Division Coordinators and Educational Consultants

2012 Summer Symposium, presented by Faculty Biographies Division Coordinators and Educational Consultants Mark Buselli Jazz Band Division Coordinator Mark Buselli is Director of Jazz Studies at Ball State University. Awards include a 2010-2011 BSU College of Fine Arts Dean’s Creative Arts Award, a Creative Renewal grant from the Indianapolis Arts Council in 2005, a teacher of the year award in 2004 at Butler University, a Creative Vision award from NUVO in May of 2007, a top 10 CD release of 2009 (December 2009) in JAZZIZ magazine for “An Old Soul,” and a top 100 CD of the decade (January 2010) in DownBeat magazine for the Buselli/Wallarab release of “Basically Baker.” Mr. Buselli has over 40 arrangements published for big bands, brass ensemble and piano/trumpet. He has nine recordings out as a leader on the Owlstudios and OA2 record labels. He has written/arranged/performed for numerous artists.Mr. Buselli currently serves as Education Director of the Buselli Wallarab Jazz Orchestra/Midcoast Swing Orchestra in Indianapolis, where he has created numerous educational opportunities for over 10,000 students. Mr. Buselli graduated from the Berklee School of Music in Boston and received his Master of Music degree in Jazz Studies from Indiana University. Thomas Caneva Concert Band Division Coordinator Dr. Thomas Caneva is Director of Bands, Professor of Music and Coordinator of Ensembles and Conducting at Ball State University. At Ball State, Dr. Caneva’s responsibilities include conducting the Wind Ensemble, coordinating the graduate wind conducting program, teaching undergraduate conducting and administering the entire band program. Under his direction, the Ball State University Wind Ensemble has performed at CBDNA Regional and National Conferences, the American Bandmasters Association Convention, and state and regional MENC conventions. -

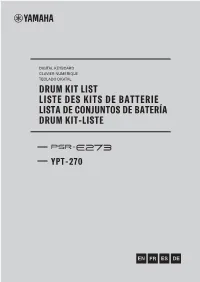

Drum Kit List

DRUM KIT LIST LISTE DES KITS DE BATTERIE LISTA DE CONJUNTOS DE BATERÍA DRUM KIT-LISTE Drum Kit List / Liste des kits de batterie/ Lista de conjuntos de batería / Drum Kit-Liste • Same as Standard Kit 1 • Comme pour Standard Kit 1 • No Sound • Absence de son • Each percussion voice uses one note. • Chaque sonorité de percussion utilise une note unique. Voice No. 117 118 119 120 121 122 Keyboard Standard Kit 1 Standard Kit 1 Indian Kit Arabic Kit SE Kit 1 SE Kit 2 Note# Note + Chinese Percussion C1 36 C 1 Seq Click H Baya ge Khaligi Clap 1 Cutting Noise 1 Phone Call C#1 37 C# 1Brush Tap Baya ke Arabic Zalgouta Open Cutting Noise 2 Door Squeak D1 38 D 1 Brush Swirl Baya ghe Khaligi Clap 2 Door Slam D#1 39 D# 1Brush Slap Baya ka Arabic Zalgouta Close String Slap Scratch Cut E1 40 E 1 Brush Tap Swirl Tabla na Arabic Hand Clap Scratch F1 41 F 1 Snare Roll Tabla tin Tabel Tak 1 Wind Chime F#1 42 F# 1Castanet Tablabaya dha Sagat 1 Telephone Ring G1 43 G 1 Snare Soft Dhol 1 Open Tabel Dom G#1 44 G# 1Sticks Dhol 1 Slap Sagat 2 A1 45 A 1 Bass Drum Soft Dhol 1 Mute Tabel Tak 2 A#1 46 A# 1 Open Rim Shot Dhol 1 Open Slap Sagat 3 B1 47 B 1 Bass Drum Hard Dhol 1 Roll Riq Tik 3 C2 48 C 2 Bass Drum Dandia Short Riq Tik 2 C#2 49 C# 2 Side Stick Dandia Long Riq Tik Hard 1 D2 50 D 2 Snare Chutki Riq Tik 1 D#2 51 D# 2 Hand Clap Chipri Riq Tik Hard 2 E2 52 E 2 Snare Tight Khanjira Open Riq Tik Hard 3 Flute Key Click Car Engine Ignition F2 53 F 2 Floor Tom L Khanjira Slap Riq Tish Car Tires Squeal F#2 54 F# 2 Hi-Hat Closed Khanjira Mute Riq Snouj 2 Car Passing -

June-July 1980

VOL. 4 NO. 3 FEATURES: CARL PALMER As a youngster, Carl Palmer exhibited tremendous drumming ability to audiences in his native England. Years later, he ex- hibited his ability to audiences world wide as one third of the legendary Emerson, Lake and Palmer. With the breakup of E.L.P., Palmer has expanded in new directions with the forma- tion of his own band, P.M. 12 BILL GOODWIN Bill Goodwin has played with a variety of musicians over the years, including Art Pepper, George Shearing, Mose Allison and currently with Phil Woods. Goodwin discusses the styles and demands of the various musicians he worked with. And though Goodwin is a renowned sideman, he is determined to branch out with some solo projects of his own. 22 DEREK PELLICCI Derek Pellicci of the successful Little River Band, speaks candidly about his responsibilities with the band versus his other love, session work. Pellicci is happiest creating under studio session pressure. The drummer also discusses the impor- tance of sound in regards to the drums and the care that must go into achieving the right sound. 28 THE GREAT JAZZ DRUMMERS: SHOP HOPPIN' AT DRUMS PART I 16 UNLIMITED 30 MD'S SECOND ANNUAL READERS POLL RESULTS 24 COLUMNS: EDITOR'S OVERVIEW 2 DRIVER'S SEAT Controlling the Band READER'S PLATFORM 5 by Mel Lewis 42 ASK A PRO 6 SHOP TALK Different Cymbals for Different Drummers IT'S QUESTIONABLE 8 by Bob Saydlowski, Jr 46 ROCK PERSPECTIVES SLIGHTLY OFFBEAT Odd Rock, Part 2 Pioneering Progressive Percussion by David Garibaldi 32 by Cheech Iero 50 JAZZ DRUMMER'S WORKSHOP DRUM -

Nº 11 Junio 2021 I.S.S.N

CONSERVATORIO SUPERIOR DE MÚSICA “ANDRÉS DE VANDELVIRA” DE JAÉN AV Notas AV Notas REVISTA DE INVESTIGACIÓN MUSICAL Nº 11 Junio 2021 I.S.S.N. 2529-8577 Catalogación y estudio de las obras de Henry Purcell en las que se incluye a la trompeta: la saga inglesa de los trompetistas de la familia de los Shore Música para una izquierda latinoamericana: el Concierto de Santiago de Mario Kuri-Aldana Trascendencia para el futuro profesional de "improvisar" con la improvisación Cinq Incantations pour flûte seule de André Jolivet. Un estudio interpretativo a través de la segunda Incantation, Pour que l’enfant qui va naître soit un fils Euphory Concerto de Adam Wesolowsi: música para nuevos tiempos Guía para el percusionista rudimental Maurice Ravel: Valses nobles et sentimentales. Estudio interpretativo AV Notas, Revista de investigación musical y artística del Conservatorio Superior de Música “Andrés de Vandelvira” de Jaén. Dirección: Calle Compañía nº 1. 23001 Jaén. Teléfono: 953 365610 Dirección Web: www.csmjaen.com Director del centro: Pedro Pablo Gordillo Castro Equipo de la revista Dirección: Sonia Segura Jerez Subcomité editorial, Nº 11: • Julia Baena Reigal • Luis Báez Cervantes • Jorge Javier Giner Gutiérrez • Sonia Segura Jerez Dirección Web: http: publicaciones.csmjaen.es Administrador del sitio web: Ángel Damián Sevilla González Contacto: [email protected] Plataforma editorial: OJS, Open Journal System ISSN: 2529-8577 Indexación: Dialnet, Latindex Catálogo 2.0, DOAJ, CiteFactor, PKP Index, OAIndex, Electra (Publicaciones Andaluzas en la Red. Biblioteca de Andalucía), Repositorio de publicaciones de Averroes. 3 4 Consejo Editorial • Dña. Elsa Calero Carramolino. Universidad de Granada • D. Albano García Sánchez, Universidad de Córdoba • Dña. -

Toto's Shannon Forrest

WORTH WIN A TAMA/MEINL PACKAGE MORE THAN $6,000 THE WORLD’S #1 DRUM MAGAZINE 25 GR E AT ’80s DRUM TRACKS Toto’s Shannon ForrestThe Quest For Excellence NEW GEAR REVIEWED! BOSPHORUS • ROLAND • TURKISH OCTOBER 2016 + PLUS + STEVEN WOLF • CHARLES HAYNES • NAVENE KOPERWEIS WILL KENNEDY • BUN E. CARLOS • TERENCE HIGGINS PURE PURPLEHEARTTM 12 Modern Drummer June 2014 CALIFORNIA CUSTOM SHOP Purpleheart Snare Ad - 6-2016 (MD).indd 1 7/22/16 2:33 PM ILL SURPRISE YOU & ILITY W THE F SAT UN VER WIL HE L IN T SP IR E Y OU 18" AA SICK HATS New Big & Ugly Big & Ugly is all about sonic Thin and very dry overall, 18" AA Sick Hats are 18" AA Sick Hats versatility, tonal complexity − surprisingly controllable. 28 holes allow them 14" XSR Monarch Hats and huge fun. Learn more. to breathe in ways other Hats simply cannot. 18" XSR Monarch With virtually no airlock, you’ll hear everything. 20" XSR Monarch 14" AA Apollo Hats Want more body, less air in your face, and 16" AA Apollo Hats the ability to play patterns without the holes 18" AA Apollo getting in your way? Just flip ‘em over! 20" AA Apollo SABIAN.COM/BIGUGLY Advertisement: New Big & Ugly Ad · Publication: Modern Drummer · Trim Size: 7.875" x 10.75" · Date: 2015 Contact: Luis Cardoso · Tel: (506) 272.1238 · Fax: (506) 272.1265 · Email: [email protected] SABIAN Ltd., 219 Main St., Meductic, NB, CANADA, E6H 2L5 YOUR BEST PERFORMANCE STARTS AT THE CORE At the core of every great performance is Carl Palmer's confidence—Confidence in your ability, your SIGNATURE 20" DUO RIDE preparation & your equipment. -

40 Drum Rudiments with Video Examples

Drum rudiment 1 Drum rudiment In percussion music, a rudiment is one of the basic patterns used in rudimental drumming. These patterns of drum strokes can be combined in many ways to create music. History The origin of snare rudiments can be traced back to Swiss mercenaries armed with long polearms. The use of pikes in close formation required a great deal of coordination. The sound of the tabor was used to set the tempo and communicate commands with distinct drumming patterns. These drumming patterns became the basis of the snare drum rudiments. The first written rudiment goes back to the year 1612 in Basel, Switzerland.[1] The cradle of rudimental drumming is said to be France, where professional drummers became part of the King's honour guard in the 17th and 18th centuries. The craft was perfected during the reign of Napoleon I. Le Rigodon is one of the cornerstones of modern rudimental drumming.[1] There have been many attempts to formalize a standard list of snare drum rudiments. The National Association of Rudimental Drummers, an organization established to promote rudimental drumming, put forward a list of 13 essential rudiments, and later a second set of 13 to form the original 26. The Percussive Arts Society reorganized the first 26 and added another 14 to form the current 40 International Drum Rudiments. Currently, the International Association of Traditional Drummers is working to once again promote the original 26 rudiments. Today there are four main Rudimental Drumming cultures: Swiss Basler Trommeln, Scottish Pipe Drumming, American Ancient Drumming, and American Modern Drumming. -

PDF: 300 Pages, 5.2 MB

The Bay Area Council Economic Institute wishes to thank the sponsors of this report, whose support was critical to its production: The Economic Institute also wishes to acknowledge the valuable project support provided in India by: The Bay Area Council Economic Institute wishes to thank the sponsors of this report, whose support was critical to its production: The Economic Institute also wishes to acknowledge the valuable project support provided in India by: Global Reach Emerging Ties Between the San Francisco Bay Area and India A Bay Area Council Economic Institute Report by R. Sean Randolph President & CEO Bay Area Council Economic Institute and Niels Erich Global Business/Transportation Consulting November 2009 Bay Area Council Economic Institute 201 California Street, Suite 1450 San Francisco, CA 94111 (415) 981-7117 (415) 981-6408 Fax [email protected] www.bayareaeconomy.org Rangoli Designs Note The geometric drawings used in the pages of this report, as decorations at the beginnings of paragraphs and repeated in side panels, are grayscale examples of rangoli, an Indian folk art. Traditional rangoli designs are often created on the ground in front of the entrances to homes, using finely ground powders in vivid colors. This ancient art form is believed to have originated from the Indian state of Maharashtra, and it is known by different names, such as kolam or aripana, in other states. Rangoli de- signs are considered to be symbols of good luck and welcome, and are created, usually by women, for special occasions such as festivals (espe- cially Diwali), marriages, and birth ceremonies. Cover Note The cover photo collage depicts the view through a “doorway” defined by the section of a carved doorframe from a Hindu temple that appears on the left. -

056-065, Chapter 6.Pdf

Chapter 6 parts played in units. To illustrate how serious the unison, and for competition had become, prizes for best g e g e d by Rick Beckham d the technological individual drummer included gold-tipped advancement of drum sticks, a set of dueling pistols, a safety v v n The rudiments and styles of n the instruments bike, a rocking chair and a set of silver loving n n i 3 i drum and bugle corps field i and implements of cups, none of which were cheap items. percussion may never have been i field music The growth of competitions continued a t a invented if not for the drum’s t competition. and, in 1885, the Connecticut Fifers and functional use in war. Drill moves i Martial music Drummers Association was established to i that armies developed -- such as m foster expansion and improvement. Annual m competition began t the phalanx (box), echelon and t less than a decade field day musters for this association h front -- were done to the beat of h following the Civil continue to this day and the individual snare the drum, which could carry up to War, birthed in and bass drum winners have been recorded e t e t m a quarter mile. m Less than 10 years after the p Civil War, fife and drum corps p u u w organized and held competitions. w These hard-fought comparisons r brought standardization and r o o m growth, to the point that, half a m century later, the technical and d d r arrangement achievements of the r o o “standstill” corps would shape the g l g drum and bugle corps percussion l c c foundation as they traded players , a and instructors.