The Piper Survey: I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1. What Are the RA and DEC of Perseus Constellation? at What Time

1. What are the RA and DEC of Perseus constellation? At what time do you expect it to transit at Kharagpur on 23 January? Does the Sun ever visit this constellation? How high in the sky from the horizon, will this constellation appear? 2. Sketch the Orion constellation, and indicate the location of the Orion nebua. What is the Orion nebula? 3. Explain briefly why Earth’s rotation axis precesses. What is the rate of precession? 4. Verify that a(1 − e2) u−1 = r = 1+ e cos φ with a = −2GM/E and e = [1+2J 2E2/G2M 2]1/2 is acually a solution to the equation 2 1 du E = J 2 + J 2u2 − GMu 2 dφ! which governs the trajectory under the gravitational attraction of a massive object. 5. Show that 4π2 P 2 = a3 GM for a general elliptic orbit. 6. Assuming that the Earth has a rotational period of 24 hrs around its own axis and revolution period of 365.25 days around the Sun, what is the length of a Solar day? After what period do distant stars come back to the same position on the sky? 7. Given Comet Halley has period 75 yrs, determine the semimajor axis of its orbit? 8. Consider an orbit around the Sun with e = 0.3. What is the ratio of the speeds at apogee and perigee? 9. At what height from center of Earth do we have geostationary satellite orbits? 10. For a central force motion in a gravitational potential α/r, show that A~ = ~v × L~ + α~r/r is conserved. -

The Puzzling Nature of Dwarf-Sized Gas Poor Disk Galaxies

Dissertation submitted to the Department of Physics Combined Faculties of the Astronomy Division Natural Sciences and Mathematics University of Oulu Ruperto-Carola-University Oulu, Finland Heidelberg, Germany for the degree of Doctor of Natural Sciences Put forward by Joachim Janz born in: Heidelberg, Germany Public defense: January 25, 2013 in Oulu, Finland THE PUZZLING NATURE OF DWARF-SIZED GAS POOR DISK GALAXIES Preliminary examiners: Pekka Heinämäki Helmut Jerjen Opponent: Laura Ferrarese Joachim Janz: The puzzling nature of dwarf-sized gas poor disk galaxies, c 2012 advisors: Dr. Eija Laurikainen Dr. Thorsten Lisker Prof. Heikki Salo Oulu, 2012 ABSTRACT Early-type dwarf galaxies were originally described as elliptical feature-less galax- ies. However, later disk signatures were revealed in some of them. In fact, it is still disputed whether they follow photometric scaling relations similar to giant elliptical galaxies or whether they are rather formed in transformations of late- type galaxies induced by the galaxy cluster environment. The early-type dwarf galaxies are the most abundant galaxy type in clusters, and their low-mass make them susceptible to processes that let galaxies evolve. Therefore, they are well- suited as probes of galaxy evolution. In this thesis we explore possible relationships and evolutionary links of early- type dwarfs to other galaxy types. We observed a sample of 121 galaxies and obtained deep near-infrared images. For analyzing the morphology of these galaxies, we apply two-dimensional multicomponent fitting to the data. This is done for the first time for a large sample of early-type dwarfs. A large fraction of the galaxies is shown to have complex multicomponent structures. -

Naming the Extrasolar Planets

Naming the extrasolar planets W. Lyra Max Planck Institute for Astronomy, K¨onigstuhl 17, 69177, Heidelberg, Germany [email protected] Abstract and OGLE-TR-182 b, which does not help educators convey the message that these planets are quite similar to Jupiter. Extrasolar planets are not named and are referred to only In stark contrast, the sentence“planet Apollo is a gas giant by their assigned scientific designation. The reason given like Jupiter” is heavily - yet invisibly - coated with Coper- by the IAU to not name the planets is that it is consid- nicanism. ered impractical as planets are expected to be common. I One reason given by the IAU for not considering naming advance some reasons as to why this logic is flawed, and sug- the extrasolar planets is that it is a task deemed impractical. gest names for the 403 extrasolar planet candidates known One source is quoted as having said “if planets are found to as of Oct 2009. The names follow a scheme of association occur very frequently in the Universe, a system of individual with the constellation that the host star pertains to, and names for planets might well rapidly be found equally im- therefore are mostly drawn from Roman-Greek mythology. practicable as it is for stars, as planet discoveries progress.” Other mythologies may also be used given that a suitable 1. This leads to a second argument. It is indeed impractical association is established. to name all stars. But some stars are named nonetheless. In fact, all other classes of astronomical bodies are named. -

X-Ray and Gamma-Ray Variability of NGC 1275

galaxies Article X-ray and Gamma-ray Variability of NGC 1275 Varsha Chitnis 1,*,† , Amit Shukla 2,*,† , K. P. Singh 3 , Jayashree Roy 4 , Sudip Bhattacharyya 5, Sunil Chandra 6 and Gordon Stewart 7 1 Department of High Energy Physics, Tata Institute of Fundamental Research, Homi Bhabha Road, Mumbai 400005, India 2 Discipline of Astronomy, Astrophysics and Space Engineering, Indian Institute of Technology Indore, Khandwa Road, Simrol, Indore 453552, India 3 Indian Institute of Science Education and Research Mohali, Knowledge City, Sector 81, SAS Nagar, Manauli 140306, India; [email protected] 4 Inter-University Centre for Astronomy and Astrophysics, Ganeshkhind, Pune 411 007, India; [email protected] 5 Department of Astronomy and Astrophysics, Tata Institute of Fundamental Research, Homi Bhabha Road, Mumbai 400005, India; [email protected] 6 Centre for Space Research, North-West University, Potchefstroom 2520, South Africa; [email protected] 7 Department of Physics and Astronomy, The University of Leicester, University Road, Leicester LE1 7RH, UK; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] (V.C.); [email protected] (A.S.) † These authors contributed equally to this work. Received: 30 June 2020; Accepted: 24 August 2020; Published: 28 August 2020 Abstract: Gamma-ray emission from the bright radio source 3C 84, associated with the Perseus cluster, is ascribed to the radio galaxy NGC 1275 residing at the centre of the cluster. Study of the correlated X-ray/gamma-ray emission from this active galaxy, and investigation of the possible disk-jet connection, are hampered because the X-ray emission, particularly in the soft X-ray band (2–10 keV), is overwhelmed by the cluster emission. -

Books, Magazines and Organizations

Contents 1 Some Background ..................................................................................... 1 The Many Types of Objects ........................................................................ 2 Telescope and Observing Essentials ........................................................... 3 Binoculars or Telescopes? ....................................................................... 3 Magnification .......................................................................................... 5 Resolution ............................................................................................... 8 Limiting Magnitude ................................................................................ 10 Field of View ........................................................................................... 11 Atmospheric Effects ................................................................................ 12 Dark Adaption and Averted Vision ......................................................... 14 Clothing................................................................................................... 16 Recording Observations .......................................................................... 17 The Science of Astronomy .......................................................................... 17 Angular Measurements ........................................................................... 18 Date and Time ......................................................................................... 18 -

Wynyard Planetarium & Observatory a Autumn Observing Notes

Wynyard Planetarium & Observatory A Autumn Observing Notes Wynyard Planetarium & Observatory PUBLIC OBSERVING – Autumn Tour of the Sky with the Naked Eye CASSIOPEIA Look for the ‘W’ 4 shape 3 Polaris URSA MINOR Notice how the constellations swing around Polaris during the night Pherkad Kochab Is Kochab orange compared 2 to Polaris? Pointers Is Dubhe Dubhe yellowish compared to Merak? 1 Merak THE PLOUGH Figure 1: Sketch of the northern sky in autumn. © Rob Peeling, CaDAS, 2007 version 1.2 Wynyard Planetarium & Observatory PUBLIC OBSERVING – Autumn North 1. On leaving the planetarium, turn around and look northwards over the roof of the building. Close to the horizon is a group of stars like the outline of a saucepan with the handle stretching to your left. This is the Plough (also called the Big Dipper) and is part of the constellation Ursa Major, the Great Bear. The two right-hand stars are called the Pointers. Can you tell that the higher of the two, Dubhe is slightly yellowish compared to the lower, Merak? Check with binoculars. Not all stars are white. The colour shows that Dubhe is cooler than Merak in the same way that red-hot is cooler than white- hot. 2. Use the Pointers to guide you upwards to the next bright star. This is Polaris, the Pole (or North) Star. Note that it is not the brightest star in the sky, a common misconception. Below and to the left are two prominent but fainter stars. These are Kochab and Pherkad, the Guardians of the Pole. Look carefully and you will notice that Kochab is slightly orange when compared to Polaris. -

The Mid-Infrared Extinction Law in the Ophiuchus, Perseus, and Serpens

The Mid-Infrared Extinction Law in the Ophiuchus, Perseus, and Serpens Molecular Clouds Nicholas L. Chapman1,2, Lee G. Mundy1, Shih-Ping Lai3, Neal J. Evans II4 ABSTRACT We compute the mid-infrared extinction law from 3.6−24µm in three molecu- lar clouds: Ophiuchus, Perseus, and Serpens, by combining data from the “Cores to Disks” Spitzer Legacy Science program with deep JHKs imaging. Using a new technique, we are able to calculate the line-of-sight extinction law towards each background star in our fields. With these line-of-sight measurements, we create, for the first time, maps of the χ2 deviation of the data from two extinc- tion law models. Because our χ2 maps have the same spatial resolution as our extinction maps, we can directly observe the changing extinction law as a func- tion of the total column density. In the Spitzer IRAC bands, 3.6 − 8 µm, we see evidence for grain growth. Below AKs =0.5, our extinction law is well-fit by the Weingartner & Draine (2001) RV = 3.1 diffuse interstellar medium dust model. As the extinction increases, our law gradually flattens, and for AKs ≥ 1, the data are more consistent with the Weingartner & Draine RV = 5.5 model that uses larger maximum dust grain sizes. At 24 µm, our extinction law is 2 − 4× higher than the values predicted by theoretical dust models, but is more consistent with the observational results of Flaherty et al. (2007). Lastly, from our χ2 maps we identify a region in Perseus where the IRAC extinction law is anomalously high considering its column density. -

A Basic Requirement for Studying the Heavens Is Determining Where In

Abasic requirement for studying the heavens is determining where in the sky things are. To specify sky positions, astronomers have developed several coordinate systems. Each uses a coordinate grid projected on to the celestial sphere, in analogy to the geographic coordinate system used on the surface of the Earth. The coordinate systems differ only in their choice of the fundamental plane, which divides the sky into two equal hemispheres along a great circle (the fundamental plane of the geographic system is the Earth's equator) . Each coordinate system is named for its choice of fundamental plane. The equatorial coordinate system is probably the most widely used celestial coordinate system. It is also the one most closely related to the geographic coordinate system, because they use the same fun damental plane and the same poles. The projection of the Earth's equator onto the celestial sphere is called the celestial equator. Similarly, projecting the geographic poles on to the celest ial sphere defines the north and south celestial poles. However, there is an important difference between the equatorial and geographic coordinate systems: the geographic system is fixed to the Earth; it rotates as the Earth does . The equatorial system is fixed to the stars, so it appears to rotate across the sky with the stars, but of course it's really the Earth rotating under the fixed sky. The latitudinal (latitude-like) angle of the equatorial system is called declination (Dec for short) . It measures the angle of an object above or below the celestial equator. The longitud inal angle is called the right ascension (RA for short). -

Fall 2005 ASTR 1120-001 General Astronomy: Stars & Galaxies

Fall 2005 ASTR 1120-001 General Astronomy: Stars & Galaxies. Problem Set 5. Due Th 17 Nov Your name: Your ID: Except for the tutorial, for which you should submit answers on line, please write your answers on this sheet, and make sure to show your working. Attach extra sheets if you need them. If you mess up, you can get another copy of the problem set at http://casa. colorado.edu/~ajsh/astr1120_05/prob.html. 1. Tutorial on Detecting Dark Matter in Spiral Galaxies Go to http://www.astronomyplace.com, press on the Cosmic Perspective 3rd Edition icon, log in. You should already have joined our class `cm651430', so that you can record your work and submit it for grade on line. Click on Tutorials, and do the tutorial on Detecting Dark Matter in Spiral Galaxies. You can redo the tutorial as often as you like, to improve your grade. Your score should be recorded automatically, but as a double check against your score disappearing into a black hole: My score was . If you like, you can comment here on the tutorial: 1 2. Recession velocity of Per A This is the observed spectrum (Kennicutt 1992) of NGC 1275, also known as Per A, the central galaxy in the Perseus cluster of galaxies. The name Per A is because it's the brightest radio source in the Perseus constellation. (a) Wavelength of Hα Measure, as accurately as you can, the wavelength of the Hα line (Hα is the leftmost of the two close prominent emission lines at the right of the graph). -

Herschel Observations of Extended Atomic Gas in the Core of the Perseus Cluster R

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Physics and Astronomy Faculty Publications Physics and Astronomy 2012 Herschel Observations of Extended Atomic Gas in the Core of the Perseus Cluster R. Mittal Rochester Institute of Technology J. B. R. Oonk Netherlands Institute for Radio Astronomy, Netherlands Gary J. Ferland University of Kentucky, [email protected] A. C. Edge Durham University, UK C. P. O'Dea Rochester Institute of Technology See next page for additional authors Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits oy u. Follow this and additional works at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/physastron_facpub Part of the Astrophysics and Astronomy Commons, and the Physics Commons Repository Citation Mittal, R.; Oonk, J. B. R.; Ferland, Gary J.; Edge, A. C.; O'Dea, C. P.; Baum, S. A.; Whelan, J. T.; Johnstone, R. M.; Combes, F.; Salomé, P.; Fabian, A. C.; Tremblay, G. R.; Donahue, M.; and H., Russell H., "Herschel Observations of Extended Atomic Gas in the Core of the Perseus Cluster" (2012). Physics and Astronomy Faculty Publications. 29. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/physastron_facpub/29 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Physics and Astronomy at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Physics and Astronomy Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Authors R. Mittal, J. B. R. Oonk, Gary J. Ferland, A. C. Edge, C. P. O'Dea, S. A. Baum, J. T. Whelan, R. M. Johnstone, F. Combes, P. Salomé, A. C. -

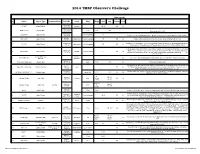

2014 Observers Challenge List

2014 TMSP Observer's Challenge Atlas page #s # Object Object Type Common Name RA, DEC Const Mag Mag.2 Size Sep. U2000 PSA 18h31m25s 1 IC 1287 Bright Nebula Scutum 20'.0 295 67 -10°47'45" 18h31m25s SAO 161569 Double Star 5.77 9.31 12.3” -10°47'45" Near center of IC 1287 18h33m28s NGC 6649 Open Cluster 8.9m Integrated 5' -10°24'10" Can be seen in 3/4d FOV with above. Brightest star is 13.2m. Approx 50 stars visible in Binos 18h28m 2 NGC 6633 Open Cluster Ophiuchus 4.6m integrated 27' 205 65 Visible in Binos and is about the size of a full Moon, brightest star is 7.6m +06°34' 17h46m18s 2x diameter of a full Moon. Try to view this cluster with your naked eye, binos, and a small scope. 3 IC 4665 Open Cluster Ophiuchus 4.2m Integrated 60' 203 65 +05º 43' Also check out “Tweedle-dee and Tweedle-dum to the east (IC 4756 and NGC 6633) A loose open cluster with a faint concentration of stars in a rich field, contains about 15-20 stars. 19h53m27s Brightest star is 9.8m, 5 stars 9-11m, remainder about 12-13m. This is a challenge obJect to 4 Harvard 20 Open Cluster Sagitta 7.7m integrated 6' 162 64 +18°19'12" improve your observation skills. Can you locate the miniature coathanger close by at 19h 37m 27s +19d? Constellation star Corona 5 Corona Borealis 55 Trace the 7 stars making up this constellation, observe and list the colors of each star asterism Borealis 15H 32' 55” Theta Corona Borealis Double Star 4.2m 6.6m .97” 55 Theta requires about 200x +31° 21' 32” The direction our Sun travels in our galaxy. -

Long-Term Study of a Gamma-Ray Emitting Radio Galaxy NGC 1275

Long-term study of a gamma-ray emitting radio galaxy NGC 1275 Yasushi Fukazawa (Hiroshima University) 8th Fermi Symposium @ Baltimore 1 Multi-wavelength variability of a gamma- ray emitting radio galaxy NGC 1275 Yasushi Fukazawa (Hiroshima University) 8th Fermi Symposium @ Baltimore 2 Outline Introduction GeV/gamma-ray and TeV studies Radio and gamma-ray connection X-ray and gamma-ray connection Optical/UV and gamma-ray connection Summary and future prospective Papers on NGC 1275 X-ray/gamma-ray studies in 2015-2018 Nustar view of the central region of the Perseus cluster; Rani+18 Gamma-ray flaring activity of NGC1275 in 2016-2017 measured by MAGIC; Magic+18 The Origins of the Gamma-Ray Flux Variations of NGC 1275 Based on Eight Years of Fermi-LAT Observations; Tanada+18 X-ray and GeV gamma-ray variability of the radio galaxy NGC 1275; Fukazawa+18 Hitomi observation of radio galaxy NGC 1275: The first X-ray microcalorimeter spectroscopy of Fe-Kα line emission from an active galactic nucleus; Hitomi+18 Rapid Gamma-Ray Variability of NGC 1275; Baghmanyan+17 Deep observation of the NGC 1275 region with MAGIC: search of diffuse γ-ray emission from cosmic rays in the Perseus cluster; Fabian+15 More papers on radio/optical observations NGC 1275 Interesting and important object for time-domain and multi-wavelength astrophysics Radio galaxies Parent population of Blazars Unlike blazars, their jet is not aligned to the line of sight, beaming is weaker. EGRET: Cen A detection and a hint of a few radio galaxies 3EG catalog: Hartman et al.