Admiralty, Shipping and Aviation Law 22

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The International Sports Law Journal 2003, No. 2

ISLJ 2003/2 Def 01-07-2004 10:13 Pagina A 2003/2 World Anti-Doping Code Kolpak Case Terror and Politics in Sport Sports Torts and Negligence Powers of USOC Dual Nature of Football Clubs Social Dialogue in European Football ISLJ 2003/2 Def 01-07-2004 10:13 Pagina B K LUWER C ONGRES *** Congres Sport & Recht Juridische actualiteiten en knelpunten op sportgebied Dinsdag 16 december 2003 • Meeting Plaza Olympisch Stadion, Amsterdam ■ Mondiale doping regelgeving: achtergrond, inhoud en praktische consequenties van de World Anti Doping Code ■ Recente uitspraken schadeaansprakelijkheid Spel en Sport (HR); deelnemers Sprekers onderling; aansprakelijkheid trainers / coaches; letselschade door paarden Mr. Fred Kollen Mr. Steven Teitler ■ Overheidssteun aan betaald voetbal; Nationale en Europese invalshoek Mr. Cor Hellingman Mr. Mark J.M. Boetekees Prof. mr. Heiko T. van Staveren ■ Verenigingsrechtelijke ontwikkelingen in de sport; bestuurlijk invulling van Mr. Hessel Schepen de tuchtrechtspraak; de positie van afdelingsverenigingen bij sportbonden en het duaal stelsel; mediation bij verenigingsrechtelijke conflicten Kosten € 575,- p.p. (excl. BTW) ■ Sportrecht bezien vanuit de rechterlijke macht Kluwer bundel 5 Sport & Recht 2003 Deze nieuwe uitgave ontvangt u bij deelname en is bij de prijs inbegrepen. ❑ Ja, ik ontvang graag meer informatie over het congres ‘Sport & Recht’ Antwoordkaart verzenden per fax of in ❑ Ja, ik wil deelnemen aan het congres ‘Sport & Recht’ open envelop zonder postzegel aan: Kluwer Opleidingen, Dhr./Mevr.: Antwoordnummer 424, 7400 VB Deventer Functie: T 0570 - 64 71 90 F 0570 - 63 69 41 Bedrijf: E [email protected] Aard van het bedrijf: W www.kluweropleidingen.nl Postbus/Straat: Kluwer legt uw gegevens vast voor de uitvoering van de overeenkomst. -

2.4 Nettleship V Weston

Law’s Fictions Reading Law as Literature Alexandra Reichelt A Thesis Presented to the Department of Literature, Area Studies, and European Languages University of Oslo In Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the MA Degree Spring 2016 I II III Law’s Fictions Reading Law as Literature Alexandra Reichelt IV © Alexandra Reichelt 2016 Law’s Fictions: Reading Law as Literature Alexandra Reichelt http://www.duo.uio.no Trykk: Reprosentralen, Universitetet i Oslo V VI Abstract This thesis seeks to explore how narrative functions in law, and how case law can be read as literature. The analysis is based on the close-reading of three central judgements in the field of negligence, a kind of tort law, in British common law. Applying narratology to law demands certain adaptations, such as the inclusion of the narrator into the implied author. There are also narratives structures that are particular to case law. The analysis focuses on three main aspects of case law as literature, in three judgements. The analysis of Donoghue v Stevenson concerns the frame narrative and the implied authors specially. The second judgement, Smith v Leech Brain, is centred around fact narratives, or statements of fact. Finally, the analysis of Nettleship v Weston focuses on competing narratives. Throughout this thesis is focused on the ethics of literature, as seen in the implied authors’ ethical standards. This thesis seeks to prove that literary analysis can be applied to case law, and that there are aspects of judgements that can only be unearthed through literary analysis. VII VIII Acknowledgements First, thank you to my supervisors, Tore Rem and Rebecca Scherr, for allowing me to explore my mad ideas and helping me do it. -

Gender Injustice in Compensating Injury to Autonomy in English and Singaporean Negligence Law

This is a repository copy of Gender injustice in compensating injury to autonomy in English and Singaporean negligence law. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/135195/ Version: Published Version Article: Keren-Paz, T. (2018) Gender injustice in compensating injury to autonomy in English and Singaporean negligence law. Feminist Legal Studies. ISSN 0966-3622 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10691-018-9390-3 Reuse This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) licence. This licence allows you to distribute, remix, tweak, and build upon the work, even commercially, as long as you credit the authors for the original work. More information and the full terms of the licence here: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Feminist Legal Studies https://doi.org/10.1007/s10691-018-9390-3 Gender Injustice in Compensating Injury to Autonomy in English and Singaporean Negligence Law Tsachi Keren‑Paz1 © The Author(s) 2018 Abstract The extent to which English law remedies injury to autonomy (ITA) as a stand-alone actionable damage in negligence is disputed. In this article I argue that the remedy available is not only partial and inconsistent (Keren-Paz in Med Law Rev, 2018) but also gendered and discriminatory against women. I irst situate the argument within the broader feminist critique of tort law as failing to appropriately remedy gendered harms, and of law more broadly as undervaluing women’s interest in reproductive autonomy. -

This Represents the Title

PRIVACY, CONSTITUTIONS AND THE LAW OF TORTS: A COMPARATIVE AND THEORETICAL ANALYSIS OF PROTECTING PERSONAL INFORMATION AGAINST DISSEMINATION IN NEW ZEALAND, THE UK AND THE USA A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Law in the University of Canterbury by Martin Heite University of Canterbury 2008 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page TABLE OF CONTENTS ..................................................................................... I ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ...................................................................................IV ABSTRACT .......................................................................................................V CHAPTER ONE - INTRODUCTION .................................................................. 1 CHAPTER TWO - THE LAW OF THE USA .................................................... 11 1 Constitutional background of the speech-privacy conflict..............................................................13 1.1 Foundations of a constitutional ‘right to privacy’............................................................................13 1.2 First Amendment viability of the public disclosure of private facts ................................................17 1.2.1 Function and doctrinal framework of the First Amendment.....................................................18 1.2.2 Early implications for New Zealand and the UK......................................................................22 1.2.3 Constitutionalisation of private law ..........................................................................................25 -

Legal Fictions in Private Law

Deus ex Machina: Legal Fictions in Private Law Liron Shmilovits Downing College Faculty of Law University of Cambridge May 2018 This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy © Liron Shmilovits 2018 Printed by Cambridge Print Solutions 1 Ronald Rolph Court Wadloes Road, Cambridge CB5 8PX United Kingdom Bound by J S Wilson & Son (Bookbinders) Ltd Unit 17 Ronald Rolph Court Wadloes Road, Cambridge CB5 8PX United Kingdom ii ABSTRACT of the PhD dissertation entitled Deux ex Machina: Legal Fictions in Private Law by Liron Shmilovits of Downing College, University of Cambridge This PhD dissertation is about legal fictions in private law. A legal fiction, broadly, is a false assumption knowingly relied upon by the courts. The main aim of the dissertation is to formulate a test for which fictions should be accepted and which rejected. Subsidiary aims include a better understanding of the fiction as a device and of certain individual fictions, past and present. This research is undertaken, primarily, to establish a rigorous system for the treatment of fictions in English law – which is lacking. Secondarily, it is intended to settle some intractable disputes, which have plagued the scholarship. These theoretical debates have hindered progress on the practical matters which affect litigants in the real world. The dissertation is divided into four chapters. The first chapter is a historical study of common-law fictions. The conclusions drawn thereform are the foundation of the acceptance test for fictions. The second chapter deals with the theoretical problems surrounding the fiction. Chiefly, it seeks precisely to define ‘legal fiction’, a recurrent problem in the literature. -

English Law Studies Programme Level 1

ENGLISH LAW STUDIES (ELS) PROGRAMME (2016-2017) Appendix 1 LEVEL 1 October-June: 250 hrs.: 100 hrs. compulsory class attendance; 150 hrs. independent study time: = 10 ECTS/20 UK credits 1. INTRODUCTORY TOPICS [items listed below can be introduced at different points in Levels 1-4] 1.1 Welcome to the course: map, a training to provide advice on English law and related legal services, a fresh chip, ‘odious comparisons’ and ‘lost translations’, dual traininG for a global world 1.2 Course method explained: exploring the ‘pond’, black-letter law, practice competencies and transferable skills, continuinG assessment, the evaluations, the ‘cut’, pass marks 1.3 ‘Skyscrapers’, ‘hole in the ground’, ‘scales’ ‘pendulum’ (the Overton Window), ‘spider’s web’ 1.4 What makes us tick? 1.5 “Islands” 1.6 What need for law (social harmony or anarchy) 1.7 Around the camp fire: deciding the substantive rules, ensurinG procedures to ensure the fair application of substantive rules (procedure) 1.8 “Lady Justice”; scales, sword, blindfold; balancing social priorities and individual freedoms, balancing the conflictinG interests of individuals 1.9 The social contract: three playing fields for everyone: ‘must do or must not do (criminal Law), ‘should do or should not do’ (tort), ‘better do or not do’ (social codes), and a fourth playing field for some: ‘to agree to do or not to do’(contract) 1.10 Why courts and judGes, how to judGe: codified principles and their application (ascertaininG the facts, applying the principle); having special regard for previous stories -

A. Requirements of a Tort: Claimant Must Have Suffered Recoverable Damage Arising from a Breach of Legal Duty Owed by Defendant

The Law of Negligence, Singapore SECTION 1 INTRODUCTION 20.1.1 In the more than eighty years since its inception as a distinct cause of action in Donoghue v Stevenson [1932] AC 562 (Donoghue), negligence has developed to become the pre-eminent tort, eclipsing older actions such as trespass, nuisance and breach of statutory duty. 20.1.2 The law of negligence in Singapore is based largely on English law, although there are areas in which the Singapore courts have chosen to depart from the principles espoused by the UK courts. While the law referred to here will, wherever possible, be that applied by the courts in Singapore (and occasionally Malaysia), reference will also be made to the jurisprudence of other jurisdictions – notably the UK and Australia – which have influenced, or are influencing, the development of the law of negligence in Singapore. A. Requirements of a tort: claimant must have suffered recoverable damage arising from a breach of legal duty owed by defendant 20.1.3 Negligence as a tort requires more than mere lack of care. A claimant who wishes to sue in negligence must show: that the defendant owed him a legal duty to take care; that there was a breach of this legal duty by the defendant; and that the breach caused him recoverable damage. SECTION 2 DUTY OF CARE: TESTS FOR ESTABLISHING DUTY A. Duty of care (1) Duty distinguishes situations in which a claim may be entertained from those where no action is possible 20.2.1 Duty is an artificial conceptual barrier which the claimant must overcome before his action can even be considered. -

What Is Tort?

CHAPTER ONE What is tort? SUMMARY The law of tort provides remedies in a wide variety of situations. Overall it has a rather tangled appearance. But there is some underlying order. This chapter tries to explain some of that order. It also reviews the main functions of the law of tort. These include deterring unsafe behaviour, giving a just response to wrongdoing, and spreading the cost of accidents broadly. The chapter then introduces two major institutions within the law of tort: the tort of negligence and the role played by statute law. Tort: Part of the law of civil wrongs 1.1 Where P sues D for a tort, P is complaining of a wrong suffered at D’s hands. The remedy P is claiming is usually a money payment. So proceedings in tort are different from criminal proceedings: in a criminal court, typically, it is not the victim of the wrong who starts the proceedings, but some official prosecutor. The remedy will also be different. A criminal court may decide that D should pay a sum of money, but if it does, the money will usually be forfeited to the state, rather than to P. (For this reason, some say that tort is about compensating P, whereas the criminal law is about punishing D. But as you will see, this begs various questions about what ‘punishment’ means; I will soon return to this issue.) 1 Style 3 (Demy).p65 1 1/10/2003, 8:12 PM → WHAT IS TORT? ← This is the most basic defining feature of tort. It is a civil, not a criminal, action. -

LEVEL 6 - UNIT 13 – Law of Tort SUGGESTED ANSWERS – June 2014

LEVEL 6 - UNIT 13 – Law of Tort SUGGESTED ANSWERS – June 2014 Note to Candidates and Tutors: The purpose of the suggested answers is to provide students and tutors with guidance as to the key points students should have included in their answers to the January 2015 examinations. The suggested answers set out a response that a good (merit/distinction) candidate would have provided. The suggested answers do not for all questions set out all the points which students may have included in their responses to the questions. Students will have received credit, where applicable, for other points not addressed by the suggested answers. Students and tutors should review the suggested answers in conjunction with the question papers and the Chief Examiners’ reports which provide feedback on student performance in the examination. SECTION A Question 1(a) In the tort of negligence ‘duty of care’ is a legal duty to take reasonable care not to harm another. It is an essential element in establishing an action in negligence. Whilst it may be possible to demonstrate that harm has been suffered as the result of carelessness, it is not possible to establish liability unless the claimant can show he was owed a duty of care. ‘A man is not liable for negligence in the air. The liability only arises where there is a duty to take care and where failure in that duty has caused damage’ per Lord Russell, Bourhill v Young (1943). The role of this requirement is to limit potential claims. Its purpose is to draw a line between those kinds of carelessness and injury for which the court considers compensation should be awarded and those for which it should not. -

An Overview of the Law of Tort Chapter 1

Page 1 CHAPTER 1 AN OVERVIEW OF THE LAW OF TORT The aim of this chapter is to consider the definition, objectives and scope of the law of tort, and to take an overview of the subject. Tort law has developed over many centuries and has its origins in an agricultural society and largely rural economy of the middle ages in Britain. It is sometimes regarded as the area of common law which remains after all the other causes of action, such as contract or breach of fiduciary duty have been subtracted. As this area of law has developed it has proved to be infinitely adaptable, but it has not developed in isolation. Other areas of law have evolved alongside tort. 1.1 WHAT IS TORT? The word ‘tort’ is derived from the Latin tortus, meaning ‘twisted’. It came to mean ‘wrong’ and it is still so used in French: ‘J’ai tort’; ‘I am wrong’. In English, the word ‘tort’ has a purely technical legal meaning – a legal wrong for which the law provides a remedy. Academics have attempted to define the law of tort, but a glance at all the leading textbooks on the subject will quickly reveal that it is extremely difficult to arrive at a satisfactory, all-embracing definition. Each writer has a different formulation, and each states that the definition is unsatisfactory. In order to understand what tort law involves, it is necessary to distinguish tort from other branches of the law, and in so doing to discover how the aims of tort differ from the aims of other areas of law such as contract law or criminal law. -

WJEC/Eduqas a Level Law Book 1 Answers

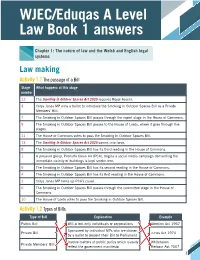

WJEC/Eduqas A Level Law Book 1 answers Chapter 1: The nature of law and the Welsh and English legal systems Law making Activity 1.1 The passage of a Bill Stage What happens at this stage number 12 The Smoking in Outdoor Spaces Act 2025 receives Royal Assent. 3 Cerys Jones MP wins a ballot to introduce the Smoking in Outdoor Spaces Bill as a Private Members’ Bill. 7 The Smoking in Outdoor Spaces Bill passes through the report stage in the House of Commons. 9 The Smoking in Outdoor Spaces Bill passes to the House of Lords, where it goes through five stages. 11 The House of Commons votes to pass the Smoking in Outdoor Spaces Bill. 13 The Smoking in Outdoor Spaces Act 2025 comes into force. 8 The Smoking in Outdoor Spaces Bill has its third reading in the House of Commons. 1 A pressure group, Promote Clean Air (PCA), begins a social media campaign demanding the immediate vicinity of buildings is kept smoke free. 5 The Smoking in Outdoor Spaces Bill has its second reading in the House of Commons. 4 The Smoking in Outdoor Spaces Bill has its first reading in the House of Commons. 2 Cerys Jones MP takes up PCA’s cause. 6 The Smoking in Outdoor Spaces Bill passes through the committee stage in the House of Commons. 10 The House of Lords votes to pass the Smoking in Outdoor Spaces Bill. Activity 1.2 Types of Bills Type of Bill Explanation Example Public Bill Will affect only individuals or corporations Abortion Act 1967 Sponsored by individual MPs who are chosen Private Bill Juries Act 1974 by a ballot to present their Bill to Parliament Involve matters of public policy which usually Whitehaven Private Members’ Bill reflect the government manifesto Harbour Act 2007 1 WJEC/Eduqas A Level Law Book 1 answers Activity 1.3 Theorist Fakebook Profiles could include the following content. -

Eastern Caribbean Supreme Court Personal Injury Cases Digest 2000-2017

EASTERN CARIBBEAN SUPREME COURT PERSONAL INJURY CASES DIGEST 2000-2017 Compiled by IMPACT JUSTICE PROJECT Caribbean Law Institute Centre The University of the West Indies Cave Hill Campus St. Michael Barbados November 2018 © Government of Canada PREFACE This volume contains digests of most of the personal injury decisions of the Eastern Caribbean Supreme Court for the period 2000 to 2017. It is one of several publications produced by IMPACT Justice (Improved Access to Justice in the CARICOM Region), a civil society justice sector project funded by the Government of Canada under an agreement with the Cave Hill Campus of the University of the West Indies. The Project focuses on improving access to justice in the CARICOM region for women, men, boys and girls by working with governments and civil society organisations to draft model laws; training legislative drafters to enhance the ability of governments to formulate their policies; promoting continuing legal education for attorneys-at-law, conducting training and encouraging the use of Alternative Dispute Resolution to build relationships and lead to peaceful solutions to issues at all levels in society and increasing knowledge of the law through a public legal education programme. Its cross cutting themes are gender equality, the environment, good governance and human rights. The digests in this volume are organized under the parts of the body which were injured and for which compensation was sought through the courts. They are intended to be a quick reference tool for use by the judiciary and other members of the legal profession in the States and Overseas Territories served by the Eastern Caribbean Supreme Court.