The Involvement of Statutory Agencies with Stanbridge

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HTS WEB Report Processor V2.1

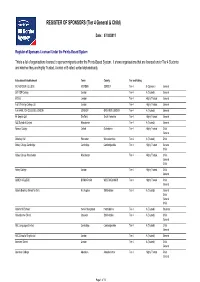

REGISTER OF SPONSORS (Tier 4 General & Child) Date : 22/06/2011 Register of Sponsors Licensed Under the Points-Based System This is a list of organisations licensed to sponsor migrants under the Points-Based System. It shows organisations that are licensed under Tier 4 Students and whether they are Highly Trusted, A-rated or B-rated, sorted alphabetically. Educational Establishment Town County Tier and Rating 3 D MORDEN COLLEGE MORDEN SURREY Tier 4 A (Trusted) General 360 GSP College London Tier 4 A (Trusted) General 4N ACADEMY LIMITED London Tier 4 B (Sponsor) General 5 E Ltd London Tier 4 Highly Trusted General A & S Training College Ltd London Tier 4 Highly Trusted General A A HAMILTON COLLEGE LONDON LONDON GREATER LONDON Tier 4 A (Trusted) General A+ English Ltd Sheffield South Yorkshire Tier 4 Highly Trusted General A2Z School of English Manchester Tier 4 A (Trusted) General Abacus College Oxford Oxfordshire Tier 4 Highly Trusted General Child Abberley Hall Worcester Worcestershire Tier 4 Highly Trusted Child Abbey College Cambridge Cambridge Cambridgeshire Tier 4 Highly Trusted General Child Abbey College Manchester Manchester Tier 4 Highly Trusted Child General Abbey College London Tier 4 Highly Trusted General Child ABBEY COLLEGE BIRMINGHAM WEST MIDLANDS Tier 4 Highly Trusted Child General Abbots Bromley School for Girls Nr. Rugeley Staffordshire Tier 4 Highly Trusted General Child Abbot's Hill School Hemel Hempstead Hertfordshire Tier 4 Highly Trusted Students Abbotsholme School Uttoxeter Staffordshire Tier 4 Highly Trusted Child -

Sixth Edition 1925 – 2000

THE SHERBORNE REGISTER Sixth Edition 1925 – 2000 “Sherborne does not consist merely of boys and masters, but there is a greater Sherborne, men young and old, living all over the world, who claim us and whom we claim as brothers and comrades bound together by a common love of our mother and the common desire to do her honour.” W. J. BENSLY, OS. 1874-1943 Editor of the Third Edition PRINTED FOR THE OLD SHIRBURNIAN SOCIETY BY Printed by Shelleys The Printers – Tel: (01935) 815364 EDITORS OF THE SHERBORNE REGISTER First Edition – – H.H.House – – – – – – 1893 Second Edition – – T.C.Rogerson – – – – – 1900 Supplement (1900-1921) C.H.Hodgson and W.J.Bensly – – – 1921 Third Edition – – W.J.Bensly – – – – – – 1937 Fourth Edition – – B.Pickering Pick – – – – – 1950 Fifth Edition – – G.G.Green and P.L.Warren – – – 1965 Sixth Edition – – M.Davenport – – – – – 1980 Supplement (1975-1990) J.R.Tozer – – – – – – 1990 Seventh Edition – – J.R.Tozer – – – – – – 2000 CONTENTS Page PREFACE – – – – – – – – – – v THE GOVERNING BODY – – – – – – – – HEADMASTERS SINCE 1850 – – – – – – – ASSISTANT MASTERS AND SCHOOL STAFF SINCE 1905 – – – THE HOUSES AND HOUSEMASTERS – – – – – – THE OLD SHIRBURNIAN SOCIETY – – – – – – NOTES ON THE ENTRIES – – – – – – – – SHIRBURNIANS 1925-2000 – – – – – –– INDEX OF SHIRBURNIANS – ––––– – INDEX OF MASTERS – – – – – – – – PREFACE SEVENTH EDITION In his preface for the Sixth Edition of the Sherborne Register, the Editor suggested that the year 2000 might be the most appropriate date for the publication of the Seventh Edition; that suggestion has been acted upon. In 1990, however, because the interval between publication of the main editions looked like being increased to 20 years (15 years having become the norm), a Supplementary Edition covering the years of entry 1975-1990 was published. -

Tier 4 - Used - Period: 01/01/2012 to 31/12/2012

Tier 4 - Used - Period: 01/01/2012 to 31/12/2012 Organisation Name Total More House School Ltd 5 3 D MORDEN COLLEGE 65 360 GSP College 15 4N ACADEMY LIMITED † 5 E Ltd 10 A A HAMILTON COLLEGE LONDON 20 A+ English Ltd 5 A2Z School of English 40 Abacus College 30 Abberley Hall † Abbey College 120 Abbey College Cambridge 140 Abbey College Manchester 55 Abbots Bromley School for Girls 15 Abbotsholme School 25 ABC School of English Ltd 5 Abercorn School 5 Aberdeen College † Aberdeen Skills & Enterprise Training 30 Aberystwyth University 520 ABI College 10 Abingdon School 20 ABT International College † Academy De London 190 Academy of Management Studies 35 ACCENT International Consortium for Academic Programs Abroad, Ltd. 45 Access College London 260 Access Skills Ltd † Access to Music 5 Ackworth School 50 ACS International Schools Limited 50 Active Learning, LONDON 5 Organisation Name Total ADAM SMITH COLLEGE 5 Adcote School Educational Trust Limited 20 Advanced Studies in England Ltd 35 AHA International 5 Albemarle Independent College 20 Albert College 10 Albion College 15 Alchemea Limited 10 Aldgate College London 35 Aldro School Educational Trust Limited 5 ALEXANDER COLLEGE 185 Alexanders International School 45 Alfred the Great College ltd 10 All Hallows Preparatory School † All Nations Christian College 10 Alleyn's School † Al-Maktoum College of Higher Education † ALPHA COLLEGE 285 Alpha Meridian College 170 Alpha Omega College 5 Alyssa School 50 American Institute for Foreign Study 100 American InterContinental University London Ltd 85 American University of the Caribbean 55 Amity University (in) London (a trading name of Global Education Ltd). -

HTS WEB Report Processor V2.1

REGISTER OF SPONSORS (Tier 4 General & Child) Date : 07/02/2011 Register of Sponsors Licensed Under the Points-Based System This is a list of organisations licensed to sponsor migrants under the Points-Based System. It shows organisations that are licensed under Tier 4 Students and whether they are Highly Trusted, A-rated or B-rated, sorted alphabetically. Educational Establishment Town County Tier and Rating 3 D MORDEN COLLEGE MORDEN SURREY Tier 4 B (Sponsor) General 360 GSP College London Tier 4 A (Trusted) General 5 E Ltd London Tier 4 Highly Trusted General A & S Training College Ltd London Tier 4 Highly Trusted General A A HAMILTON COLLEGE LONDON LONDON GREATER LONDON Tier 4 A (Trusted) General A+ English Ltd Sheffield South Yorkshire Tier 4 Highly Trusted General A2Z School of English Manchester Tier 4 A (Trusted) General Abacus College Oxford Oxfordshire Tier 4 Highly Trusted Child General Abberley Hall Worcester Worcestershire Tier 4 A (Trusted) Child Abbey College Cambridge Cambridge Cambridgeshire Tier 4 Highly Trusted General Child Abbey College Manchester Manchester Tier 4 Highly Trusted Child General Child Abbey College London Tier 4 Highly Trusted Child General ABBEY COLLEGE BIRMINGHAM WEST MIDLANDS Tier 4 Highly Trusted Child General Abbots Bromley School for Girls Nr. Rugeley Staffordshire Tier 4 A (Trusted) General Child General Child Abbot's Hill School Hemel Hempstead Hertfordshire Tier 4 A (Trusted) Students Abbotsholme School Uttoxeter Staffordshire Tier 4 A (Trusted) Child General ABC Languages Limited Cambridge -

Access the Word, Access the World

Dyslexia Contact Access the word, access the world The Official Magazine of the British Dyslexia Association Vol. 31 No. 1 www.bda dyslexia.org.uk January 2012 £3.00 Advertisement Independent Day and Boarding School . for Boys and Girls Aged 10–18 . College ales LL30 1RD s id’ St David’s College are now enrolling boys and girls into Year 6 We aim to ease the transition into secondary education by offering a full Year 6 programme, taught by our highly qualified specialist staff. Year Llandudno, North W 6 pupils will benefit from the vast range of courses and facilities on offer at St David’s that includes an extensive outdoor education, sports and activities St Dav programme which complements rigorous but sympathetic academic studies. Year 6 pupils will be afforded their own academic base, common room, play space and lunchtime break in order to acclimatise slowly into secondary education. Following on from Year 6 there will be a natural progression on to our full programme of studies up to GCE and A Level. Each and every child will be nurtured along the way by a team of academic and support staff dedicated to the ‘whole person’ ethos of education. Broad range of GCEs, A Levels (including Psychology, Philosophy, Photography and Performing Arts) and vocational courses (including City and Guilds: Computer Aided Engineering). Amazing variety of Outdoor Education activities and qualifications in addition to a BTEC in Sport. Individual education plan for each pupil including study skills and exam preparation. At the forefront of SEN provision for over 40 years. -

List of Approved Training Bodies for Compulsory Basic Training

LIST OF APPROVED TRAINING BODIES FOR COMPULSORY BASIC TRAINING COUNTY OF ABERDEENSHIRE Report Date: 30/10/2012 COUNTY/TOWN SITE LOCATION NAME OF ATB ABERDEENSHIRE GOLF ROAD CAR PARK CALEDONIA MOTORCYCLE SERVICES ABERDEEN PITTODRIE STADIUM 244 King Street ABERDEEN AB24 5QH ABERDEEN AB24 5BW : ABERDEENSHIRE WOODHILL HOUSE 2112 BIKE TRAINING ABERDEEN WESTBURN ROAD LOWER BODACHRA WHITESTRIPES ABERDEEN AB16 5GB ABERDEEN ABERDEENSHIRE AB21 7AP ABERDEENSHIRE GRAMPIAN POLICE GRAMPIAN POLICE ABERDEEN DRIVING SCHOOL POLICE HEADQUARTERS NELSON STREET QUEEN STREET ABERDEEN AB24 5EQ ABERDEEN ABERDEENSHIRE AB24 5EQ ABERDEENSHIRE NORTHFIELD ACADEMY ABERDEEN BIKE SCHOOL ABERDEEN 14 ST. JOHNS TERRACE MANNOFIELD ABERDEEN AB16 7AU ABERDEEN AB15 7PH : ABERDEENSHIRE LOWER BODACHRA 2112 BIKE TRAINING ABERDEEN WHITESTRIPES LOWER BODACHRA DYCE WHITESTRIPES ABERDEEN AB21 7AP ABERDEEN ABERDEENSHIRE AB21 7AP : 1 ABERDEENSHIRE GORDON BARRACKS RIGHT START MOTORING LTD BRIDGE OF DON GREEN BRAE FARM HOUSE LONGSIDE BRIDGE OF DON AB23 8DB PETERHEAD ABERDEENSHIRE AB42 4TX ABERDEENSHIRE ONE SPORTS BIKETEC M/CYCLE TRG BRIDGE OF DON TOP FLOOR FLAT 1 CARDEN TERRACE BRIDGE OF DON AB22 8GT ABERDEEN AB10 1US ABERDEENSHIRE THE GABLES (BRIDGE OF DON) ALL RIDERS BRIDGE OF DON BRIDGE OF DON 3 LEDDACH PLACE BRIDGE OF DON AB23 8BT WESTHILL ABERDEENSHIRE AB32 6FW ABERDEENSHIRE ABERDEENSHIRE COUNCIL BIKETEC M/CYCLE TRG INVERURIE GORDON HOUSE TOP FLOOR FLAT BLACKHALL ROAD 1 CARDEN TERRACE INVERURIE AB51 3WA ABERDEEN AB10 1US ABERDEENSHIRE PETERHEAD ACADEMY RIGHT START MOTORING LTD PETERHEAD -

THE FT TOP INDEPENDENT SCHOOLS FINANCIAL TIMES SPECIAL REPORT | Saturday September 13 2008

THE FT TOP INDEPENDENT SCHOOLS FINANCIAL TIMES SPECIAL REPORT | Saturday September 13 2008 www.ft.com/independentschools2008 Right answer: pupils study mathematics at the independent King Edward VI High School for Girls in Birmingham, which came 9th in the FT ranking this year Getty How to read the great rebellion Simon Briscoe and land and Wales, and Scottish subjects, such as physical time to publish league this year’s results. But read- that only one in nine schools offering Highers and education, do not demand tables, because we are using ers should also beware that achieves the AAB grades in David Turner look A-levels. Many have also the same intellectual ability results before re-marks. some schools that would be core subjects that most of at the FT ranking achieved great results Ð from pupils. Moreover, the But 2007 data suggest post- near the bottom of the table the top universities require some given a fair wind range of exams offered is re-marking adjustments without a mitigating circum- from successful private of school A-level because they can dictate increasingly broad, includ- made very little difference to stance, such as an expertise school candidates. results and assess entry through academic abil- ing the International Bacca- a school’s aggregate position in Special Educational Needs Thankfully, all is not lost. ity, and some despite having laureate and new Pre-U as in the rankings for that year. children, may have with- Most schools still judge that the decision of to take more or less whoever an alternative to A-levels, Moreover, cynics have drawn to avoid publicity of no harm is done by letting many not to take can pay. -

Week Ending 4Th April 2008

TEST VALLEY BOROUGH COUNCIL – PLANNING SERVICES _____________________________________________________________________________________________________________ WEEKLY LIST OF PLANNING APPLICATIONS AND NOTIFICATIONS : NO. 13 Week Ending: 4th April 2008 _____________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Comments on any of these matters should be forwarded IN WRITING (including fax and email) to arrive before the expiry date shown in the second to last column For the Northern Area to: For the Southern Area to: Head of Planning Head of Planning Beech Hurst Council Offices Weyhill Road Duttons Road ANDOVER SP10 3AJ ROMSEY SO51 8XG In accordance with the provisions of the Local Government (Access to Information Act) 1985, any representations received may be open to public inspection. You may view applications and submit comments on-line – go to www.testvalley.gov.uk APPLICATION NO./ PROPOSAL LOCATION APPLICANT CASE OFFICER/ PREVIOUS REGISTRATION PUBLICITY APPLICA- TIONS DATE EXPIRY DATE 08/00882/TREEN T1 - Pine tree - fell and The School House, Red Rice Duncan Haigh Miss Rachel Cooke 02.04.2008 remove stump Road, Abbotts Ann, Andover 29.04.2008 ABBOTTS ANN Hampshire SP11 7BG 08/00920/LBWN Provision of a new rear 25 Red Rice Road, Abbotts Mrs Shirley Miss Sarah Barter YES 04.04.2008 entrance Ann, Andover, Hampshire Featherstone 02.05.2008 ABBOTTS ANN SP11 7BG 08/00742/FULLN Erection of single storey front 12 Blendon Drive, Andover, Barry Knight Miss Sarah Barter 03.04.2008 extension to -

Ranking Reflects Unsettling Times

Top Independent Schools FINANCIAL TIMES SPECIAL REPORT | Saturday September 10 2011 www.ft.com/independentschools2011 | www.twitter.com/ftreports In this issue Charity inquiry A landmark judgment will determine the public benefits schools must provide Page 2 Value for money Parents may be better off opting for chains rather than the big name schools Page 4 Technology The independent sector has not been left behind in the IT race Page 5 Switching sectors Even the wealthy may consider sending their offspring to staterun schools at some point Page 6 Marketing Schools are increasingly turning to professional persuaders to make sure clients keep coming through the door Page 7 Rankings The FT’s Road to success: Magdalen College School in Oxford has taken first place in the independent school league table this year guide to the UK’s top independent establishments Pages 811 Ranking ref lects unsettling times Pupil development Rounded The different orget Buster private school has not just within England, an ment to compare qualifi- personalities are Douglas beating topped it. Does this mean extremely difficult task. cations. But these are cur- qualifications on Mike Tyson in Westminster has lost its What is the correct rently under review, and part of the offer have added 1990 or Wimble- killer instinct? Well, no. exchange rate to apply there is a suspicion that package Fdon beating Liverpool to Its decline (to sixth place) when comparing results the Pre-U is under- Page to the complexity win the FA Cup in 1988. coincides with its attained in the Interna- weighted in this metric. -

Institution Code Institution Title a and a Co, Nepal

Institution code Institution title 49957 A and A Co, Nepal 37428 A C E R, Manchester 48313 A C Wales Athens, Greece 12126 A M R T C ‐ Vi Form, London Se5 75186 A P V Baker, Peterborough 16538 A School Without Walls, Kensington 75106 A T S Community Employment, Kent 68404 A2z Management Ltd, Salford 48524 Aalborg University 45313 Aalen University of Applied Science 48604 Aalesund College, Norway 15144 Abacus College, Oxford 16106 Abacus Tutors, Brent 89618 Abbey C B S, Eire 14099 Abbey Christian Brothers Grammar Sc 16664 Abbey College, Cambridge 11214 Abbey College, Cambridgeshire 16307 Abbey College, Manchester 11733 Abbey College, Westminster 15779 Abbey College, Worcestershire 89420 Abbey Community College, Eire 89146 Abbey Community College, Ferrybank 89213 Abbey Community College, Rep 10291 Abbey Gate College, Cheshire 13487 Abbey Grange C of E High School Hum 13324 Abbey High School, Worcestershire 16288 Abbey School, Kent 10062 Abbey School, Reading 16425 Abbey Tutorial College, Birmingham 89357 Abbey Vocational School, Eire 12017 Abbey Wood School, Greenwich 13586 Abbeydale Grange School 16540 Abbeyfield School, Chippenham 26348 Abbeylands School, Surrey 12674 Abbot Beyne School, Burton 12694 Abbots Bromley School For Girls, St 25961 Abbot's Hill School, Hertfordshire 12243 Abbotsfield & Swakeleys Sixth Form, 12280 Abbotsfield School, Uxbridge 12732 Abbotsholme School, Staffordshire 10690 Abbs Cross School, Essex 89864 Abc Tuition Centre, Eire 37183 Abercynon Community Educ Centre, Wa 11716 Aberdare Boys School, Rhondda Cynon 10756 Aberdare College of Fe, Rhondda Cyn 10757 Aberdare Girls Comp School, Rhondda 79089 Aberdare Opportunity Shop, Wales 13655 Aberdeen College, Aberdeen 13656 Aberdeen Grammar School, Aberdeen Institution code Institution title 16291 Aberdeen Technical College, Aberdee 79931 Aberdeen Training Centre, Scotland 36576 Abergavenny Careers 26444 Abersychan Comprehensive School, To 26447 Abertillery Comprehensive School, B 95244 Aberystwyth Coll of F. -

Stanbridge Earls School Review Report

Stanbridge Earls School Review Report Overview This report is made pursuant to an Inquiry to consider the inspection history of Stanbridge Earls School from January 2011 to January 2013. The Inquiry was set up in the light of safeguarding concerns raised by the parents of two pupils at the school and the conclusions reached by a First-Tier Tribunal in respect of the school in January 2013. It summarises the outcomes of an internal review which was carried out to consider Ofsted’s involvement during this period and the three inspections that took place. The internal review concluded that each of the inspections conducted during this period was problematic but for different reasons. Each failed to get underneath concerns at the school. This report provides a detailed summary, including findings and recommendations, for consideration by the Inquiry. Introduction Ofsted’s aim is to ensure, through effective inspection and regulation, that outcomes for children and young people are improved by the receipt of better care, services, and education. Improved outcomes can only be achieved if children are safe from harm. Therefore, safeguarding the welfare of children is part of our core business. In this regard, Ofsted has an overarching statutory duty to have regard to the need to safeguard and promote the rights and welfare of children set out in s117(2) (a) and s119(3) (a) of the Education and Inspection Act, 2006. The legal basis for the inspection of welfare in residential special schools is set out in the Children Act 1989 as amended by the Care Standards Act 2000. -

Inquiry Report Stanbridge Earls School Trust

Inquiry Report Stanbridge Earls School Trust Registered Charity Number 307342 A statement of the results of an inquiry into Stanbridge Earls School Trust (registered charity number 307342). Published on 1 December 2014. The charity Stanbridge Earls School Trust (‘the Charity’) was registered on 26 February 1964. It is governed by memorandum and articles of association dated 23 November 1951 and last amended by resolutions dated 13 and 29 May 2013. Its objects are to advance education, by the provision and conduct of a day and/or boarding school for boys and girls by ancillary or incidental education activities and other associated activities for the benefit of the community. In practice, the Charity, which is based in Hampshire, provided boarding and day education for boys and girls with special educational needs. The specific learning difficulties of pupils included dyslexia, dyspraxia and dyscalculia, and some who have social and communication difficulties such as Asperger’s syndrome and mild autism. More details about the Charity are available on the register of charities. Background and context leading up to the opening of the inquiry In June 2012 the Charity Commission was notified by the Charity that proceedings had been initiated by a parent on behalf of their child at the school in the First Tier Tribunal for Special Educational Needs and Disability (‘the Tribunal’) for a claim for disability discrimination under various provisions of the Equalities Act 2010. Proceedings in respect of a claim for sexual discrimination were also initiated in the County Court. The case in the Tribunal was heard during November and December 2012 and found in favour of the appellant.