Fractional Identities: the Political Arithmetic of Aboriginal Victorians

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Twenty Fifth Report of the Central Board for the Protection of The

1889. VICTORIA. TWENTY-FIFTH REPORT OF THE BOARD TOR THE PROTECTION OF THE ABORIGINES IN THE COLONY OF VICTORIA. PRESENTED TO BOTH HOUSES OF PARLIAMENT BY HIS EXCELLENCY'S COMMAND By Authority: ROBT. S. BRAIN, GOVERNMENT PRINTER, MELBOURNE. No. 129.—[!•.]—17377. Digitised by AIATSIS Library, SF 25.3/1 - www.aiatsis.gov.au APPROXIMATE COST OF REPORT. Preparation— Not given, £ s. d. Printing (760 copies) ., .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 25 0 0 Digitised by AIATSIS Library, SF 25.3/1 - www.aiatsis.gov.au REPORT. 4th November, 1889. SIR, The Board for the Protection of the Aborigines have the honour to submit for Your Excellency's consideration their Twenty-fifth Report on the condition of the Aborigines of this colony, together with the reports from the managers of the stations, and other papers. 1. The Board have held two special and eight ordinary meetings during the past year. 2. The average numbers of Aborigines and half-castes who have resided on the various stations during the year are as follow:— Coranderrk, under the management of Mr. Shaw 78 Framlingham, „ „ Mr. Goodall 90 Lake Condah, „ „ Revd. J. H. Stable 84 Lake Wellington, „ „ Revd. F. A. Hagenauer 61 Lake Tyers, „ „ Revd. John Bulmer 60 Lake Hindmarsh, „ „ Revd. P. Bogisch 48 421 Others visit the stations and reside there during short periods of the year. 3. The number of half-castes, who, under the operation of the new Act for the merging of half-castes among the general population of the colony, are earning their living with some assistance from the Board is 113. 4. Rations and clothing are still supplied to those of the half-castes who, according to the " Amended Act," satisfy the Board of their necessitous circum stances. -

Koorie Heritage Trust Annual Report 2015 – 2016 Contents

Koorie Heritage Trust Annual Report 2015 – 2016 Contents Page 2 Wominjeka/Welcome: Vision and Purpose Page 5 Chairperson’s Report Page 6 Chief Executive Officer’s Report Page 12 Our Programs Koorie Family History Service Cultural Education Retail and Venue Hire Collections, Exhibitions and Public Programs Page 42 Activities Page 43 Donors and Supporters Page46 Governance Page 48 Staff Page 50 Financial Report www.koorieheritagetrust.com ABN 72 534 020 156 The Koorie Heritage Trust acknowledges and pays respect to the Traditional Custodians of Melbourne, on whose lands we are located. Warning: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders are advised that this document may contain the names and/or images of people who have passed away. Cover Image: Koorie Heritage Trust, view from level 2, Yarra Building. Photo James Murcia, 2015 Terminology Design: Darren Sylvester The term Koorie is commonly used to describe Aboriginal people of Southeast Australia; Editor: Virginia Fraser however, we recognise the diversity of Aboriginal people living throughout Victoria including Publication Co-ordinator: Giacomina Pradolin Koories and other Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander (ATSI) people from around Australia. We Text: Koorie Heritage Trust staff have used the term Aboriginal in parts of the report to include all people of ATSI descent. Wominjeka/Welcome: Vision and Purpose Our Vision To live in a society where Aboriginal culture and history are a fundamental part of Victorian life. Our Purpose To promote, support and celebrate the continuing journey of the Aboriginal people of South Eastern Australia. Our Motto Gnokan Danna Murra Kor-ki/Give me your hand my friend. Our Values Respect, honesty, reciprocity, curiosity. -

Australian Aboriginal Verse 179 Viii Black Words White Page

Australia’s Fourth World Literature i BLACK WORDS WHITE PAGE ABORIGINAL LITERATURE 1929–1988 Australia’s Fourth World Literature iii BLACK WORDS WHITE PAGE ABORIGINAL LITERATURE 1929–1988 Adam Shoemaker THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY E PRESS iv Black Words White Page E PRESS Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] Web: http://epress.anu.edu.au Previously published by University of Queensland Press Box 42, St Lucia, Queensland 4067, Australia National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Black Words White Page Shoemaker, Adam, 1957- . Black words white page: Aboriginal literature 1929–1988. New ed. Bibliography. Includes index. ISBN 0 9751229 5 9 ISBN 0 9751229 6 7 (Online) 1. Australian literature – Aboriginal authors – History and criticism. 2. Australian literature – 20th century – History and criticism. I. Title. A820.989915 All rights reserved. You may download, display, print and reproduce this material in unaltered form only (retaining this notice) for your personal, non-commercial use or use within your organization. All electronic versions prepared by UIN, Melbourne Cover design by Brendon McKinley with an illustration by William Sandy, Emu Dreaming at Kanpi, 1989, acrylic on canvas, 122 x 117 cm. The Australian National University Art Collection First edition © 1989 Adam Shoemaker Second edition © 1992 Adam Shoemaker This edition © 2004 Adam Shoemaker Australia’s Fourth World Literature v To Johanna Dykgraaf, for her time and care -

'The Happiest Time of My Life …': Emotive Visitor Books and Early

‘The happiest time of my life …’: Emotive visitor books and early mission tourism to Victoria’s Aboriginal reserves1 Nikita Vanderbyl On the afternoon of 16 January 1895, a group of visitors to the Gippsland Lakes, Victoria, gathered to perform songs and hymns with the Aboriginal residents of Lake Tyers Aboriginal Mission. Several visitors from the nearby Lake Tyers House assisted with the preparations and an audience of Aboriginal mission residents and visitors spent a pleasant summer evening performing together and enjoying refreshments. The ‘program’ included an opening hymn by ‘the Aborigines’ followed by songs and hymns sung by friends of the mission, the missionary’s daughter and a duet by two Aboriginal women, Mrs E. O’Rourke and Mrs Jennings, who in particular received hearty applause for their performance of ‘Weary Gleaner’. The success of this shared performance is recorded by an anonymous hand in the Lake Tyers visitor book, noting that 9 pounds 6 shillings was collected from the enthusiastic audience.2 The missionary’s wife, Caroline Bulmer, was most likely responsible for this note celebrating the success of an event that stands out among the comments of visitors to Lake Tyers. One such visitor was a woman named Miss Florrie Powell who performed the song ‘The Old Countess’ after the duet by Mrs O’Rourke and Mrs Jennings. She wrote effusively in the visitor book that ‘to give you an idea 1 Florrie Powell 18 January 1895, Lake Tyers visitor book, MS 11934 Box 2478/5, State Library of Victoria. My thanks to Tracey Banivanua Mar, Diane Kirkby, Catherine Bishop, Lucy Davies and Kate Laing for their feedback on an earlier draft of this article, and to Richard White for mentoring as part of a 2015 Copyright Agency Limited Bursary. -

WISDOM MAN to the Future of My People the River Knows (Kuuyang

WISDOM MAN To the future of my people The River Knows (Kuuyang – Eel Song) Shane Howard, Neil Murray and Banjo Clarke Who’s going to save this country now? Who’ll protect its sacred power? Listen to the south-west wind Listen can you hear the spirits sing? See the wild birds fill the sky Hear the plover’s warning cry Feel the wind and feel the rain Falling on the river once again The river knows The river flows That old river knows Watch us come and go The south-west wind brings Autumn rain To fill the rivers once again The eels will make their journey now Longing for that salty water Down the Tuuram stones they slither In their thousands down the river Headed for the river mouth Fat and sleek and slowly moving south All the tribes will gather here Travel in from everywhere Food to share and things to trade Song and dance until it fades Hear the stories being told Handed down to young from old See the fires burning there Hear the voices echo through the air Listen can you hear their song? Singin’ as they move along? Movin’ through that country there All the stories gathered here The kuuyang* move into the ocean Restless motion Even though they go away The spirits all return to here again * Eels ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Camilla Chance and Banjo Clarke’s family would like to thank the following people for their help and support in making this book possible: above all, Elizabeth (Libby) Clarke, the historian among Banjo’s children and a greatly honoured keeper of traditional ways; Camilla is much indebted to her for her input into her father’s book. -

Atomic Thunder: the Maralinga Story

ABORIGINAL HISTORY Volume forty-one 2017 ABORIGINAL HISTORY Volume forty-one 2017 Published by ANU Press and Aboriginal History Inc. The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at press.anu.edu.au All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Aboriginal History Incorporated Aboriginal History Inc. is a part of the Australian Centre for Indigenous History, Research School of Social Sciences, The Australian National University, and gratefully acknowledges the support of the School of History and the National Centre for Indigenous Studies, The Australian National University. Aboriginal History Inc. is administered by an Editorial Board which is responsible for all unsigned material. Views and opinions expressed by the author are not necessarily shared by Board members. Members of the Editorial Board Maria Nugent (Chair), Tikka Wilson (Secretary), Rob Paton (Treasurer/Public Officer), Ingereth Macfarlane (Co-Editor), Liz Conor (Co-Editor), Luise Hercus (Review Editor), Annemarie McLaren (Associate Review Editor), Rani Kerin (Monograph Editor), Brian Egloff, Karen Fox, Sam Furphy, Niel Gunson, Geoff Hunt, Dave Johnston, Shino Konishi, Harold Koch, Ann McGrath, Ewen Maidment, Isabel McBryde, Peter Read, Julia Torpey, Lawrence Bamblett. Editors: Ingereth Macfarlane and Liz Conor; Book Review Editors: Luise Hercus and Annemarie McLaren; Copyeditor: Geoff Hunt. About Aboriginal History Aboriginal History is a refereed journal that presents articles and information in Australian ethnohistory and contact and post-contact history of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. -

Performing Aboriginality: Desiring Pre-Contact Aboriginality in Victoria, 1886–1901

This is a peer-reviewed, post-print (final draft post-refereeing) version of the following published document: Peck, Julia ORCID: 0000-0001-5134-2471 (2010) Performing Aboriginality: Desiring Pre-contact Aboriginality in Victoria, 1886–1901. History of Photography, 34 (3). pp. 214-233. doi:10.1080/03087291003765802 Official URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03087291003765802 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03087291003765802 EPrint URI: http://eprints.glos.ac.uk/id/eprint/3277 Disclaimer The University of Gloucestershire has obtained warranties from all depositors as to their title in the material deposited and as to their right to deposit such material. The University of Gloucestershire makes no representation or warranties of commercial utility, title, or fitness for a particular purpose or any other warranty, express or implied in respect of any material deposited. The University of Gloucestershire makes no representation that the use of the materials will not infringe any patent, copyright, trademark or other property or proprietary rights. The University of Gloucestershire accepts no liability for any infringement of intellectual property rights in any material deposited but will remove such material from public view pending investigation in the event of an allegation of any such infringement. PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR TEXT. This is a peer-reviewed, post-print (final draft post-refereeing) version of the following published document: Peck, Julia (2010). Performing Aboriginality: Desiring Pre-contact Aboriginality in Victoria, 1886– 1901.History of Photography, 34 (3), 214-233. ISSN 0308-7298 Published in History of Photography, and available online at: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/03087291003765802 We recommend you cite the published (post-print) version. -

Provenance 2008

Provenance 2008 Issue 7, 2008 ISSN: 1832-2522 Index About Provenance 2 Editorial 4 Refereed articles 6 Lyn Payne The Curious Case of the Wollaston Affair 7 Victoria Haskins ‘Give to us the People we would Love to be amongst us’: The Aboriginal Campaign against Caroline Bulmer’s Eviction from Lake Tyers Aboriginal Station, 1913-14 19 Robyn Ballinger Landscapes of Abundance and Scarcity on the Northern Plains of Victoria 28 Belinda Robson From Mental Hygiene to Community Mental Health: Psychiatrists and Victorian Public Administration from the 1940s to 1990s 36 Annamaria Davine Italian Speakers on the Walhalla Goldfield: A Micro-History Approach 48 Forum articles 58 Karin Derkley ‘The present depression has brought me down to zero’: Northcote High School during the 1930s 59 Ruth Dwyer A Jewellery Manufactory in Melbourne: Rosenthal, Aronson & Company 65 Dawn Peel Colac 1857: Snapshot of a Colonial Settlement 73 Jenny Carter Wanted! Honourable Gentlemen: Select Applicants for the Position of Deputy Registrar for Collingwood in 1864 82 Peter Davies ‘A lonely, narrow valley’: Teaching at an Otways Outpost 89 Brienne Callahan The ‘Monster Petition’ and the Women of Davis Street 96 1 About Provenance The journal of Public Record Office Victoria Provenance is a free journal published online by Editorial Board Public Record Office Victoria. The journal features peer- reviewed articles, as well as other written contributions, The editorial board includes representatives of: that contain research drawing on records in the state • Public Record Office Victoria access services; archives holdings. • the peak bodies of PROV’s major user and stakeholder Provenance is available online at www.prov.vic.gov.au groups; The purpose of Provenance is to foster access to PROV’s • and the archives, records and information archival holdings and broaden its relevance to the wider management professions. -

A Brief History of the Lake Tyers Aboriginal Community; the Lake Tyers Aboriginal Community Has Had a Controversial History Since Being Set up in 1861

A brief history of the Lake Tyers Aboriginal community; The Lake Tyers Aboriginal community has had a controversial history since being set up in 1861. Waters, Jeff . ABC Premium News ; Sydney [Sydney]21 Dec 2013. ProQuest document link ABSTRACT (ABSTRACT) Nine years later, Victoria's Aboriginal protection board voted for a policy of concentrating all 'full-blood' and 'half- caste' Aboriginal people on the Lake Tyers Station. In an interview she told ABC Gippsland her childhood as one of 11 children at Lake Tyers was "happy and carefree", but that all changed when her family was pressured to leave the mission. According to the ABC's Mission Beats website: "Between 1956 and 1965, the residents requested, protested and petitioned for Lake Tyers Mission Station to become an independent, Aboriginal run farming cooperative. This campaign received support and assistance from the Melbourne-based Aborigines Advancement League (AAL), with Pastor Sir Doug Nichols providing a much-needed voice among Melbourne's bureaucrats. When the Board moved to close Lake Tyers in February 1963, Nichols resigned his position on the Board in protest." FULL TEXT The traditional owners of the land which includes what is now called Lake Tyers in East Gippsland are the Krowathunkooloong clan - one of five forming the Gunaikurnai nation, who largely resisted white settlement in the area. In 1861 the Lake Tyers Mission Station was established by the Church of England missionary Reverend John Bulmer, to house some of the Gunaikurnai survivors of the conflict. The peninsula, which has a lake on each side, was known to its traditional owners as Bung Yarnda. -

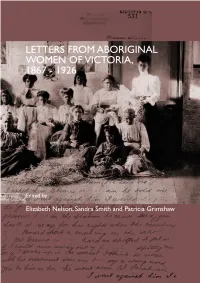

Letters from Aboriginal Women of Victoria, 1867-1926, Edited by Elizabeth Nelson, Sandra Smith and Patricia Grimshaw (2002)

LETTERS FROM ABORIGINAL WOMEN OF VICTORIA, 1867 - 1926 LETTERS FROM ABORIGINAL WOMEN OF VICTORIA, 1867 - 1926 Edited by Elizabeth Nelson, Sandra Smith and Patricia Grimshaw History Department The University of Melbourne 2002 © 2002 Copyright is held on individual letters by the individual contributors or their descendants. No reproduction without permission. All rights reserved. Published in 2002 by The History Department The University of Melbourne Melbourne, Australia The National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry: Letters from aboriginal women in Victoria, 1867-1926. ISBN 0 7340 2160 7. 1. Aborigines, Australian - Women - Victoria - Correspondence. 2. Aborigines, Australian - Women - Victoria - Social conditions. 3. Aborigines, Australian - Government policy - Victoria. 4. Victoria - History. I. Grimshaw, Patricia, 1938- . II. Nelson, Elizabeth, 1972- . III. Smith, Sandra, 1945- . IV. University of Melbourne. Dept. of History. (Series : University of Melbourne history research series ; 11). 305.8991509945 Front cover details: ‘Raffia workers at Coranderrk’ Museum of Victoria Photographic Collection Reproduced courtesy Museum Victoria Layout and cover design by Design Space TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements 7 Map 9 Introduction 11 Notes on Editors 21 The Letters: Children and family 25 Land and housing 123 Asserting personal freedom 145 Regarding missionaries and station managers 193 Religion 229 Sustenance and material assistance 239 Biographical details of the letter writers 315 Endnotes 331 Publications 357 Letters from Aboriginal Women of Victoria, 1867 - 1926 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We have been helped to pursue this project by many people to whom we express gratitude. Patricia Grimshaw acknowledges the University of Melbourne Small ARC Grant for the year 2000 which enabled transcripts of the letters to be made. -

Aboriginal History Journal: Volume 1

Aboriginal History Volume one 1977 ABORIGINAL HISTORY Editorial Board and Management Committee 1977 Diane Barwick and Robert Reece (Editors) Andrew Markus (Review Editor) Niel Gunson (Chairman) Peter Grimshaw (Treasurer) Peter Corris Luise Hercus Hank Nelson Charles Rowley Ann Curthoys Isabel McBryde Nicolas Peterson Lyndall Ryan National Committee for 1977 Jeremy Beckett Mervyn Hartwig F.D. McCarthy Henry Reynolds Peter Biskup George Harwood John Mulvaney John Summers Greg Dening Ron Lampert Charles Perkins James Urry A.P. Elkin M.E. Lofgren Marie Reay Jo Woolmington Aboriginal History aims to present articles and information in the field of Australian ethnohistory, particularly the post-contact history of the Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders. Historical studies based on anthro pological, archaeological, linguistic and sociological research, including comparative studies of other ethnic groups such as Pacific Islanders in Australia, will be welcomed. Future issues will include recorded oral traditions and biographies, vernacular narratives with translations, pre viously unpublished manuscript accounts, resumes of current events, archival and bibliographical articles, and book reviews. Aboriginal History is administered by an Editorial Board which is respon sible for all unsigned material in the journal. Views and opinions expressed by the authors of signed articles and reviews are not necessarily shared by Board members. The editors invite contributions for consideration; reviews will be commissioned by the review editor. Contributions, correspondence and enquiries concerning price and availa bility should be sent to: The Editors, Aboriginal History Board, c/- Research School of Pacific Studies, The Australian National University, GPO Box 4, Canberra, A.C.T. 2600, Australia. Reprinted 1988. ABORIGINAL HISTORY VOLUME ONE 1977 PART 1 CONTENTS ARTICLES W. -

Special List Index for GRG52/90

Special List GRG52/90 Newspaper cuttings relating to aboriginal matters This series contains seven volumes of newspaper clippings, predominantly from metropolitan and regional South Australian newspapers although some interstate and national newspapers are also included, especially in later years. Articles relate to individuals as well as a wide range of issues affecting Aboriginals including citizenship, achievement, sport, art, culture, education, assimilation, living conditions, pay equality, discrimination, crime, and Aboriginal rights. Language used within articles reflects attitudes of the time. Please note that the newspaper clippings contain names and images of deceased persons which some readers may find distressing. Series date range 1918 to 1970 Index date range 1918 to 1970 Series contents Newspaper cuttings, arranged chronologically Index contents Arranged chronologically Special List | GRG52/90 | 12 April 2021 | Page 1 How to view the records Use the index to locate an article that you are interested in reading. At this stage you may like to check whether a digitised copy of the article is available to view through Trove. Articles post-1954 are unlikely to be found online via Trove. If you would like to view the record(s) in our Research Centre, please visit our Research Centre web page to book an appointment and order the records. You may also request a digital copy (fees may apply) through our Online Enquiry Form. Agency responsible: Aboriginal Affairs and Reconciliation Access Determination: Open Note: While every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of special lists, some errors may have occurred during the transcription and conversion processes. It is best to both search and browse the lists as surnames and first names may also have been recorded in the registers using a range of spellings.