The Mongolian and Oirat Translations of the Sutra of Golden Light

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Animal Release: the Dharma Being Staged Between Marketplace and Park

Cultural Diversity in China 2015; 1(2): 141–163 Research Article Open Access Der-Ruey Yang* Animal Release: The Dharma Being Staged between Marketplace and Park# DOI 10.1515/cdc-2015-0008 # This paper is an outcome of the research project “The Transmis- Received September 14, 2014 accepted January 1, 2015 sion and Acceptance of Religion: An Exploration of Cognitive Anth- ropology and Psychology (宗教的传习与接受—认知人类学与心理学 Abstract: Despite having been sharply criticized and 的探索)” (project no. 10YJA730016), funded by the Humanities and ridiculed on ecological and/or theological grounds by Social Science Foundation of the Ministry of Education of China. people both in and outside the Buddhist community for decades, fangsheng (animal release) is still one of the The booming of Buddhism in China since the end of most popular devotional acts among Chinese Buddhists, the Cultural Revolution has been evident for all to see. especially urban Buddhists. In fact, to the dismay of According to Ji (2012–13), probably the most up-to-date and those enlightened critics, this controversial practice may comprehensive synthesis of survey results about the growth well be one of the key factors that have made Buddhism of Buddhism in China in recent decades, the population of the fastest-growing religion in China in recent decades. self-identified Buddhist believers in China has increased This paper thus attempts to explain why Chinese urban from less than 70 million in 1997 to 100 million in 2005 and Buddhists persistently favor fangsheng. It begins with then to around 230 million (18.2 percent of the total Chinese a brief review of the process by which famous Buddhist population) in 2010. -

Golden Light Sutra for World Peace

Recite The Golden Light Sutra For World Peace Anybody who wants peace in the world should read The Golden Light Sutra (Ser.ö dam.päi do wang.gyi gyälpo). This is a very important practice to stop violence and wars in the world. The Golden Light Sutra is one of the most beneficial ways to bring peace. This is something that everyone can do, no matter how busy you are, even if you can read one page a day, or a few lines and in this way continually read The Golden Light Sutra. The holy Golden Light Sutra is the king of the sutras. It is extremely powerful and fulfills all one's wishes, as well as bringing peace and happiness for all sentient beings, up to enlightenment. It is also extremely powerful for world peace, for your own protection and for the protection of the country and the world. Also, it has great healing power for people in the country. For anyone who desires peace for themselves and for others this is the spiritual, or Dharma, way to bring peace that doesn't require you to harm others, doesn't require you to criticize others or even to demonstrate against others, yet can accomplish peace. Anyone can read this text, Buddhists and even non-Buddhists who desire world peace. This also protects individuals and the country from what are labeled natural disasters of the wind element, fire element, earth element and water element, such as earthquakes, floods, cyclones, fires, tornadoes, etc. They are not natural because they come from causes and conditions that make dangers happen. -

Recite the Sublime SUTRA of GOLDEN LIGHT, Especially

HOW TO PRACTICE WORLD PEACE? Recite the sublime SUTRA OF GOLDEN LIGHT, especially in groups Lama Zopa Rinpoche tells us that actions performed by a group have much greater karmic results than those performed alone. Consider reciting the Sutra of Golden Light by joining or organizing a group recitation. Group recitations can occur at any time. Consider scheduling recitations specifically for days of great merit. To create a group, people might gather at their center or join a distance recitation through yahoo.groups. Contact other dharma students and designate a time when everyone recites. Then, report the results, experiences and questions here: www.fpmt.org/golden_light_sutra/default.asp#report Why recite the exalted king of sutras, Sublime Golden Light? This is a powerful practice for world peace, purification of obscurations and accumulation of merit. Here are some ways to organize a group recitation. Please report what you do. For the Fifteen Days of Miracles, 2010, recitation of the sublime sutra was ongoing, both beginning at 6 a.m. at the Mahabodhi Stupa in Bodhgaya, hosted by Root Institute, and by distance world-wide. Participants onsite began with refuge prayers, bodhicitta motivation, and specific motivation for reciting the sutra. Chapter one was recited together, and then participants recited individually. All recited chapter 21 together, followed by dedication and long-life prayers. Lama Tsong Khapa Institute reports that often, when new people come to the Centre, they like to recite sutras together, and in particular, the Golden Light Sutra. This could be a way of welcoming new people into a centre’s activities and shared practices. -

PACIFIC WORLD Journal of the Institute of Buddhist Studies

PACIFIC WORLD Journal of the Institute of Buddhist Studies Third Series Number 14 Fall 2012 FRONT COVER PACIFIC WORLD: Journal of the Institute of Buddhist Studies Third Series, Number 14 Fall 2012 SPINE PACIFIC WORLD Journal of the Institute of Buddhist Studies HALF-TITLE PAGE i REVERSE HALF TITLE ii PACIFIC WORLD Journal of the Institute of Buddhist Studies Third Series Number 14 Fall 2012 TITLE iii Pacific World is an annual journal in English devoted to the dissemination of his- torical, textual, critical, and interpretive articles on Buddhism generally and Shinshu Buddhism particularly to both academic and lay readerships. The journal is distributed free of charge. Articles for consideration by the Pacific World are welcomed and are to be submitted in English and addressed to the Editor, Pacific World, 2140 Durant Ave., Berkeley, CA 94704-1589, USA. Acknowledgment: This annual publication is made possible by the donation of BDK America of Berkeley, California. Guidelines for Authors: Manuscripts (approximately twenty standard pages) should be typed double-spaced with 1-inch margins. Notes are to be endnotes with full biblio- graphic information in the note first mentioning a work, i.e., no separate bibliography. See The Chicago Manual of Style (16th edition), University of Chicago Press, §16.3 ff. Authors are responsible for the accuracy of all quotations and for supplying complete references. Please e-mail electronic version in both formatted and plain text, if possible. Manuscripts should be submitted by February 1st. Foreign words should be underlined and marked with proper diacriticals, except for the following: bodhisattva, buddha/Buddha, karma, nirvana, samsara, sangha, yoga. -

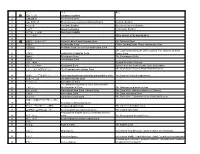

中文梵文英文1 佛釋迦牟尼佛sakyamuni Buddha 2 毘盧遮那佛

中文 梵文 英文 1 佛 釋迦牟尼佛 Sakyamuni Buddha 2 毘盧遮那佛 Vairocana Buddha 3 藥師璢璃光佛 Bhaiṣajya-guru-vaiḍūrya-prabhāṣa Buddha Medicine Buddha 4 阿彌陀佛 Amitābha Buddha Boundless radiance Buddha 5 不動佛 Akṣobhya Buddha Unshakable Buddha 6 然燈佛, 定光佛 Dipamkara Buddha 7 東方青龍佛 Azure Dragon of the East Buddha 8 9 經 金剛般若波羅密多經 Vajracchedika Prajñā Pāramitā Sutra The Diamond Sutra 10 華嚴經 Avataṃsaka Sutra Flower Garland Sutra; Flower Adornment Sutra 11 阿彌陀經 Amitābha Sutra; Shorter Sukhāvatīvyūha Sūtra The Lotus Sutra; Discourse of the Lotus of True Dharma; Dharma 12 法華經 Saddharma Puṇḍarīka Sutra Flower Sutra; 13 楞嚴經 Śūraṅgama Sutra The Shurangama Sutra 14 楞伽經 Lankāvatāra Sūtra 15 四十二章經 Sutra in Forty-two Sections 16 地藏菩薩本願經 Kṣitigarbha Sutra Sutra of the Past Vows of Earth Store Bodhisattva 17 心經 ; 般若波羅蜜多心經 The Prajnaparamita Hrdaya Sutra The Heart Sutra, Heart of Prajñā Pāramitā Sutra 18 圓覺經;大方广圆觉修多罗了义经 Mahāvaipulya pūrṇabuddhasūtra prassanārtha sūtra The Sutra of Perfect Enlightenment 19 維摩詰所說經 Vimalakīrti-nirdeśa sūtra 20 三摩地王经 Samadhi-raja Sutra The Mahā prajñā pāramitā-sūtra; Śatasāhasrikā 21 大般若經 Prajñāpāramitā Sūtra; The Maha prajna paramita sutras 22 大般涅槃經 Mahā parinirvāṇa Sutra, Nirvana Sutra The Sutra of the ultimate extinction of Dharma 23 梵網經 Brahmajāla Sutra The Sutra of Brahma's Net 24 解深密經 Sandhinirmocana Sutra The Sutra of the Explanation of the Profound Secrets 勝鬘経;勝鬘師子吼一乘大方便方 25 廣經 Śrīmālādevī Siṃhanāda Sūtra 26 佛说观无量寿佛经;十六觀經 Amitayur-dhyana Sutra The sixteen contemplate sutra 27 金光明經;金光明最勝王經 Suvarṇa-prabhāsa-uttamarāja Sutra The Golden-light Sutra -

WINTER 2015 “ Eeing One’S Nature, Becoming Enlightened, and Attaining S Buddhahood Are Open to Everyone

WINTER 2015 “ eeing one’s nature, becoming enlightened, and attaining S buddhahood are open to everyone. Believe it or not, you have come here to listen to a Dharma talk, so you will eventually attain buddhahood. This is worth being happy about. It’s not just I who is saying this: this is what the Buddhist scriptures tell us. Some might say, ‘But I haven’t taken refuge in the Three Jewels, so I’m not even a Buddhist. I just came to listen a little bit, and you say that I’ll attain buddhahood. I don’t believe it!’ But this is exactly what the sutras tell us. Fascicle 36 of the Mahaparinirvana Sutra says, ‘All sentient beings, without exception, have buddha-nature. Icchantikas [the most base and spiritually deluded of all beings], who defame the Mahayana teachings, commit the five heinous crimes, and violate the four grave prohibitions, will also certainly achieve the bodhi path.’ All sentient beings have buddha-nature, even if they don’t believe in the Buddha’s teachings, even if they defame the Buddhist sutras and perpetrate evils such as patricide, matricide, killing an arhat, disrupting the harmony of a monastic sangha, causing a buddha to bleed, killing people, sexual misconduct, theft and robbery, and telling serious lies, as long as they have heard the Buddha’s teaching of the Dharma, they will definitely become enlightened and attain buddhahood.” — Chan Master Sheng Yen excerpt from Key to Chan, 1995 Volume 35, Number 1 — Winter 2015 CHAN MAGAZINE PUBLISHED QUARTERLY BY Institute of Chung-Hwa Buddhist Culture Reading Sutras as a Spiritual Practice 4 Chan Meditation Center (CMC) by Chan Master Sheng Yen 90-56 Corona Avenue Elmhurst, NY 11373 The Arising of Conditioned Appearance 12 FOUNDER/TEACHER Chan Master Venerable Dr. -

GOLDEN LIGHT SUTRA Experiences and Dedications As of March, 2018

GOLDEN LIGHT SUTRA Experiences and Dedications As of March, 2018 GD: I dedicate this recitation to the fulfillment of Lama Zopa's Enlightened Activities and may my father, who has died and is traveling the bardo, receive the merit too, along with all beings in the intermediate state. May all beings suffering end and all their happiness never cease. CCS: I have read Golden Light Sutra aloud 3 times so far during Losar. Thanks to all the Venerable Masters & wonderful compassionate people with FPMT. MANY MANY THANKS AW: Recited the GLS today, the lunar eclipse and full moon day for world peace, long life of Lama Zopa Rinpoche, success of FPMT Dharma Education in the UK, especially at Jamyang London at this time, and for my sons to be successful in their relationships. EM: I have been thinking on complementing my altar with a sacred text.One night at Bodhgaya I woke up after realizing in my dream that the text on my altar should be the Golden Light Sutra. That seems perfect, in particular because my Guru HH Ayang Rinpoche was recognized as the reincarnation of a Terton whom, on Buddha’s time, was Bodhisattva Ruchiraketu (mentioned in this sutra) GB: First completed recitation was dedicated to the healing and long life of I. P. who had aggressive lymphoma, now in remission!! The second recitation was dedicated to the protection, healing and long life of Sogyal Rinpoche and stability in the Rigpa Sangha. AW: Dedicated to peace in the middle east, and the long life of Lama Zopa Rinpoche HK: Thank you for putting the Golden Light Sutra on the internet. -

July-September 2010, Volume 37(PDF)

July-Sept. 2010 Vol. 37 DHARMA WORLD for Living Buddhism and Interfaith Dialogue CONTENTS Tackling the Question "What Is the Lotus Sutra?" The International Lotus Sutra Seminar by Gene Reeves 2 Cover image: Abinitio Design. Groping Through the Maze of the Lotus Sutra by Miriam Levering 5 The International Lotus Sutra Seminar 2 A Phenomenological Answer to the Question "What Is the Lotus Sutra?" by Donald W. Mitchell 9 DHARMA WORLD presents Buddhism as The Materiality of the Lotus Sutra: Scripture, Relic, a practical living religion and promotes and Buried Treasure by D. Max Moerman 15 interreligious dialogue for world peace. It espouses views that emphasize the dignity oflife, seeks to rediscover our inner nature The Lotus Sutra Eludes Easy Definition: A Report and bring our lives more in accord with it, on the Fourteenth International Lotus Sutra Seminar and investigates causes of human suffering. by Joseph M. Logan 23 It tries to show how religious principles help solve problems in daily life and how Groping Through the Maze of the least application of such principles has the Lotus Sutra 5 wholesome effects on the world around us. Reflections It seeks to demonstrate truths that are fun Like the Lotus Blossom by Nichiko Niwano 31 damental to all religions, truths on which all people can act. The Buddha's Teachings Affect All of Humankind by Nikkyo Niwano 47 Niwano Peace Prize Women, Work, and Peace by Ela Ramesh Bhatt 32 Publisher: Moriyasu Okabe The Materiality of Executive Director: Jun'ichi Nakazawa the Lotus Sutra 15 Director: Kazumasa Murase Interview Editor: Kazumasa Osaka True to Self and Open to Others Editorial Advisors: An interview with Rev. -

Sutra of Golden Light Oral Transmission by Kirti Tsenshab Rinpoche

Sutra of Golden Light Oral Transmission by Kirti Tsenshab Rinpoche A Transcript of the Commentary Preliminary Teaching Day One Please listen to the teachings by generating the motivation in accordance with the tradition from the lineage lamas, thinking that I must attain the unsurpassable, fully completed state of the peerless enlightenment for the benefit of all sentient beings that pervades the infinitude of space. In order to accomplish this, I am going to listen to these pure dharma teachings. Taking a quotation from that of Lama Tsong Khapa who says that, “ Of all the Buddha’s activities, that which is most supreme of all those activities is the activity of the speech”. You have the miraculous activities of the holy body and that of the holy mind and that of the holy speech. You have in general the twelve deeds, as we know of, and then also a slightly more elaborate version which is presented as the twelve-fold different activities of the Buddha. The most elaborate version is the 100 deeds of the Buddha. In reflecting upon the kindness of the Buddha, cherishing the kindness of the Buddha, remembering the kindness of the Buddha, there are six different ways one can reflect upon these remembrances. One is remembrance of the Buddha, remembrance of the Dharma, remembrance of the Sangha, remembrance of the Deity, remembrance of the Emptiness and - Lama Zopa: “ remembrance on Charity” - remembrance of Charity. These are the six forms of remembrances. In remembering the Buddha, you can remember the extensive deeds of the Buddha, the much extensive deeds of the Buddha and amongst these extensive deeds, the one we cherish most above all is the Buddha’s activities of the holy speech. -

Rethinking Japan's Earliest Written Narratives: Early-Heian Kundokugo

Rethinking Japan’s Earliest Written Narratives Title : Early-Heian Kundokugo Translations of Chinese Buddhist Texts Author(s) Bundschuh, John Citation 越境文化研究イニシアティヴ論集. 3 P.43-P.63 Issue Date 2020-03-31 Text Version publisher URL http://hdl.handle.net/11094/75561 DOI rights Note Osaka University Knowledge Archive : OUKA https://ir.library.osaka-u.ac.jp/ Osaka University Rethinking Japan’s Earliest Written Narratives Rethinking Japan’s Earliest Written Narratives: Early-Heian Kundokugo Translations of Chinese Buddhist Texts JOHN BUNDSCHUH* 1 Introduction The earliest examples of fully-formed written Japanese come from the poetry and imperial edicts of the Nara period (710–794 C.E.). However, examples of extended narrative prose do not appear until the Heian period (794–1185 C.E.). While Taketori Monogatari ( The Tale of the Bamboo Cutter) is often cited as the earliest Japanese narrative, even the oldest estimates of its origin place it in the latter half of the ninth century. Thus Taketori Monogatari was predated by early-ninth-century Japanese translations of Buddhist sutras that include full narratives in the form of parables and didactic tales of past reincarnations of the Buddha. These tales were read in kundokugo ( ), the linguistic variety that arose from transposing and reciting Chinese texts in Japanese, which is as old as the act of reading itself in Japan. The religious and political classes who learned, copied, and propagated Buddhist sutras during the Heian period used kundokugo when reciting them in Japanese. In the Nara period, Emperor Shōmu created a network of Kokubunji temples and ordered monks throughout the country to copy and recite the Golden Light Sutra ( Konkōmyō Saishō Ōkyō) in order for the imperial household and the realm to gain divine protection. -

Celebrate the Buddha's Enlightenment

MAY/JUN 2015 MCI (P) 078/02/2015 1 Celebrate the Buddha’s Enlightenment The Best Way to Amitabha Buddhist Centre is a centre Celebrate Vesak Day for the study and practice of Mahayana Buddhism, based on the tradition of Lama Tsong Khapa, in the lineage of Lama Thubten Yeshe and our Spiritual Director, Kyabje Lama Zopa Rinpoche. Vesak Day falls on 1st June this year. What is the significance of Vesak and what is the most OUR VISION To all TASHI DELEK readers and meaningful way to celebrate the day? Here is how Khen Rinpoche Geshe Chonyi explained Learn to Be Happy ABC members and friends: “The Significance of Vesak Day” at Vesak Celebration 2014. Courage to cherish all Wisdom to see the truth May your celebration of the Buddha’s day Faith in Buddha’s peace of birth, enlightenment and parinirvana be oday is Vesak Day, the day remember that this is the best way to therefore Buddha said do not create Follow Our Four-fold Path Inspire blessed and wish fulfilling! Buddha came to this world. celebrate Vesak Day. It is the best way any negative action. Whatever we Connect TToday is the Buddha’s birthday. to repay the Buddha’s kindness. It is suffer, unhappiness, suffering, pain, Learn Today is the day Buddha became the best way to repay your parents’ everything, sickness, comes from our Practise fully enlightened. Also, today is the kindness. If you like Buddha then own negative actions in the past. day Buddha showed passing into always remember the advice. Buddha th hether it is Vesak Day or the Saka Dawa 15 as observed on the parinirvana. -

Performing the Jeweled Pagoda Mandalas: Relics, Reliquaries, and a Realm of Text

The Art Bulletin ISSN: 0004-3079 (Print) 1559-6478 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rcab20 Performing the Jeweled Pagoda Mandalas: Relics, Reliquaries, and a Realm of Text Halle O'Neal To cite this article: Halle O'Neal (2015) Performing the Jeweled Pagoda Mandalas: Relics, Reliquaries, and a Realm of Text, The Art Bulletin, 97:3, 279-300, DOI: 10.1080/00043079.2015.1009326 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/00043079.2015.1009326 View supplementary material Published online: 23 Sep 2015. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 723 View Crossmark data Citing articles: 1 View citing articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rcab20 Performing the Jeweled Pagoda Mandalas: Relics, Reliquaries, and a Realm of Text Halle O’Neal At first glance, the characters swirl around, haphazard and Mimi Yiengpruksawan have discussed the mandalas in any tiny (Fig. 1–3). Picking out a few familiar words provides tem- real detail. In her book Paintings of the Lotus Sutra,Tanabe porary stability, but a moment later the viewer is lost again considered the Tanzan Shrine and Ryuhonji mandalas as in a sea of shining script at once accessible and remote. Nei- examples of the twelfth-century trend that emphasized ther legible nor completely illegible, these discombobulating narrative description of sutra content in the art of the and intriguing characters are specifically alegible. This vision Lotus Sutra.8 She saw the jeweled