Annemieke+M.Kiers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Plant Propagation Protocol for [Agoseris Retrorsa] ESRM 412](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6182/plant-propagation-protocol-for-agoseris-retrorsa-esrm-412-96182.webp)

Plant Propagation Protocol for [Agoseris Retrorsa] ESRM 412

Plant Propagation Protocol for [Agoseris retrorsa] ESRM 412 – Native Plant Production Protocol URL: https://courses.washington.edu/esrm412/protocols/[USDASpeciesCode.pdf] North American Distribution Northwest Distribution Source oF Map Images: USDA PLANTS Database (1) TAXONOMY Plant Family ScientiFic Name Asteraceae / Compositae Common Name Aster Family Species ScientiFic Name ScientiFic Name Agoseris retrorsa Varieties N/A Sub-species N/A Cultivar N/A Common Synonym(s) Macrorhynchus retrorsus Microrhynchus angustifolius Troximon retrorsum (4) Common Name(s) Spearleaved agoseris Spearleaf agoseris (2) Spear-leaved mountain dandelion (6), (7) Species Code (as per USDA Plants AGRE database) GENERAL INFORMATION Geographical range Agoseris retrorsa is a perennial herb that is dominant and native to the western portion oF the United States. Specifically, it is native to California, Nevada, Idaho, Orgeon, Utah, and Washington (3). See map above. Ecological distribution Establishes in ecosystems such as scrub, chaparral and coniFerous forest (3). Climate and elevation range Ability to grow in dry habitat at low to high elevations (2). Specific elevation ideal for growth located at 400 to 2300m (4). Local habitat and abundance ( Agoseris retrorsa can be found in a range of habitats that contain slopes and ridges, and dry open woods. In Washington they are found along the eastern edges of the Cascade Mts. near Chelan County (2). Plant strategy type / successional Weedy/ Colonizer stage Plant characteristics Spearleaf agoseris is a forb. It is perennial wildFlower herb, which has a base of leaves about several of erect, thick, wool-coated inflorescences up to 2½ feet in height (2). PROPAGATION DETAILS Ecotype InFormation not available For speciFic plant Propagation Goal Plants Seed in spring, light soil cover no more than 1/8 inch (4) Propagation Method Seed (4) Product Type Container (plug) (4) Stock Type 5.5 cu. -

Genetic Resources Collections of Leafy Vegetables (Lettuce, Spinach, Chicory, Artichoke, Asparagus, Lamb's Lettuce, Rhubarb An

Genet Resour Crop Evol (2012) 59:981–997 DOI 10.1007/s10722-011-9738-x RESEARCH ARTICLE Genetic resources collections of leafy vegetables (lettuce, spinach, chicory, artichoke, asparagus, lamb’s lettuce, rhubarb and rocket salad): composition and gaps R. van Treuren • P. Coquin • U. Lohwasser Received: 11 January 2011 / Accepted: 21 July 2011 / Published online: 7 August 2011 Ó The Author(s) 2011. This article is published with open access at Springerlink.com Abstract Lettuce, spinach and chicory are gener- nl/cgn/pgr/LVintro/. Based on a literature study, an ally considered the main leafy vegetables, while a analysis of the gene pool structure of the crops was fourth group denoted by ‘minor leafy vegetables’ performed and an inventory was made of the distri- includes, amongst others, rocket salad, lamb’s lettuce, bution areas of the species involved. The results of asparagus, artichoke and rhubarb. Except in the case these surveys were related to the contents of the of lettuce, central crop databases of leafy vegetables newly established databases in order to identify the were lacking until recently. Here we report on the main collection gaps. Priorities are presented for update of the international Lactuca database and the future germplasm acquisition aimed at improving the development of three new central crop databases for coverage of the crop gene pools in ex situ collections. each of the other leafy vegetable crop groups. Requests for passport data of accessions available Keywords Chicory Á Crop database Á Germplasm to the user community were addressed to all known availability Á Lettuce Á Minor leafy vegetables Á European collection holders and to the main collec- Spinach tion holders located outside Europe. -

Suitability of Root and Rhizome Anatomy for Taxonomic

Scientia Pharmaceutica Article Suitability of Root and Rhizome Anatomy for Taxonomic Classification and Reconstruction of Phylogenetic Relationships in the Tribes Cardueae and Cichorieae (Asteraceae) Elisabeth Ginko 1,*, Christoph Dobeš 1,2,* and Johannes Saukel 1,* 1 Department of Pharmacognosy, Pharmacobotany, University of Vienna, Althanstrasse 14, Vienna A-1090, Austria 2 Department of Forest Genetics, Research Centre for Forests, Seckendorff-Gudent-Weg 8, Vienna A-1131, Austria * Correspondence: [email protected] (E.G.); [email protected] (C.D.); [email protected] (J.S.); Tel.: +43-1-878-38-1265 (C.D.); +43-1-4277-55273 (J.S.) Academic Editor: Reinhard Länger Received: 18 August 2015; Accepted: 27 May 2016; Published: 27 May 2016 Abstract: The value of root and rhizome anatomy for the taxonomic characterisation of 59 species classified into 34 genera and 12 subtribes from the Asteraceae tribes Cardueae and Cichorieae was assessed. In addition, the evolutionary history of anatomical characters was reconstructed using a nuclear ribosomal DNA sequence-based phylogeny of the Cichorieae. Taxa were selected with a focus on pharmaceutically relevant species. A binary decision tree was constructed and discriminant function analyses were performed to extract taxonomically relevant anatomical characters and to infer the separability of infratribal taxa, respectively. The binary decision tree distinguished 33 species and two subspecies, but only five of the genera (sampled for at least two species) by a unique combination of hierarchically arranged characters. Accessions were discriminated—except for one sample worthy of discussion—according to their subtribal affiliation in the discriminant function analyses (DFA). However, constantly expressed subtribe-specific characters were almost missing and even in combination, did not discriminate the subtribes. -

Pattern of Callose Deposition During the Course of Meiotic Diplospory in Chondrilla Juncea (Asteraceae, Cichorioideae)

Protoplasma DOI 10.1007/s00709-016-1039-y ORIGINAL ARTICLE Pattern of callose deposition during the course of meiotic diplospory in Chondrilla juncea (Asteraceae, Cichorioideae) Krystyna Musiał1 & Maria Kościńska-Pająk1 Received: 21 September 2016 /Accepted: 26 October 2016 # The Author(s) 2016. This article is published with open access at Springerlink.com Abstract Total absence of callose in the ovules of dip- Keywords Apomixis . Callose . Megasporogenesis . Ovule . losporous species has been previously suggested. This paper Chondrilla . Rush skeletonweed is the first description of callose events in the ovules of Chondrilla juncea, which exhibits meiotic diplospory of the Taraxacum type. We found the presence of callose in the Introduction megasporocyte wall and stated that the pattern of callose de- position is dynamically changing during megasporogenesis. Callose, a β-1,3-linked homopolymer of glucose containing At the premeiotic stage, no callose was observed in the ovules. some β-1,6 branches, may be considered as a histological Callose appeared at the micropylar pole of the cell entering marker for a preliminary identification of the reproduction prophase of the first meioticdivision restitution but did not mode in angiosperms. In the majority of sexually reproducing surround the megasporocyte. After the formation of a restitu- flowering plants, the isolation of the spore mother cell and the tion nucleus, a conspicuous callose micropylar cap and dis- tetrad by callose walls is a striking feature of both micro- and persed deposits of callose were detected in the megasporocyte megasporogenesis (Rodkiewicz 1970; Bhandari 1984; Bouman wall. During the formation of a diplodyad, the micropylar 1984; Lersten 2004). -

DANDELION Taraxacum Officinale ERADICATE

OAK OPENINGS REGION BEST MANAGEMENT PRACTICES DANDELION Taraxacum officinale ERADICATE This Best Management Practice (BMP) document provides guidance for managing Dandelion in the Oak Openings Region of Northwest Ohio and Southeast Michigan. This BMP was developed by the Green Ribbon Initiative and its partners and uses available research and local experience to recommend environmentally safe control practices. INTRODUCTION AND IMPACTS— Dandelion (Taraxacum officinale) HABITAT—Dandelion prefers full sun and moist, loamy soil but can is native to Eurasia and was likely introduced to North America many grow anywhere with 3.5-110” inches of annual precipitation, an an- times. The earliest record of Dandelion in North America comes from nual mean temperature of 40-80°F, and light. It is tolerant of salt, 1672, but it may have arrived earlier. It has been used in medicine, pollutants, thin soils, and high elevations. In the OOR Dandelion has food and beverages, and stock feed. Dandelion is now widespread been found on sand dunes, in and at the top of floodplains, near across the planet, including OH and MI. vernal pools and ponds, and along roads, ditches, and streams. While the Midwest Invasive Species Information Net- IDENTIFICATION—Habit: Perennial herb. work (MISIN) has no specific reports of Dandelion in or within 5 miles of the Oak Openings Region (OOR, green line), the USDA Plants Database reports Dan- D A delion in all 7 counties of the OOR and most neighboring counties (black stripes). Dan- delion is ubiquitous in the OOR. It has demonstrated the ability to establish and MI spread in healthy and disturbed habitats of OH T © Lynn Sosnoskie © Steven Baskauf © Chris Evans the OOR and both the wet nutrient rich soils of wet prairies and floodplains as well Leaves: Highly variable in shape, color and hairiness in response to as sandy dunes and oak savannas. -

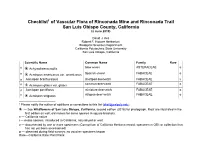

Rinconada Checklist-02Jun19

Checklist1 of Vascular Flora of Rinconada Mine and Rinconada Trail San Luis Obispo County, California (2 June 2019) David J. Keil Robert F. Hoover Herbarium Biological Sciences Department California Polytechnic State University San Luis Obispo, California Scientific Name Common Name Family Rare n ❀ Achyrachaena mollis blow wives ASTERACEAE o n ❀ Acmispon americanus var. americanus Spanish-clover FABACEAE o n Acmispon brachycarpus shortpod deervetch FABACEAE v n ❀ Acmispon glaber var. glaber common deerweed FABACEAE o n Acmispon parviflorus miniature deervetch FABACEAE o n ❀ Acmispon strigosus strigose deer-vetch FABACEAE o 1 Please notify the author of additions or corrections to this list ([email protected]). ❀ — See Wildflowers of San Luis Obispo, California, second edition (2018) for photograph. Most are illustrated in the first edition as well; old names for some species in square brackets. n — California native i — exotic species, introduced to California, naturalized or waif. v — documented by one or more specimens (Consortium of California Herbaria record; specimen in OBI; or collection that has not yet been accessioned) o — observed during field surveys; no voucher specimen known Rare—California Rare Plant Rank Scientific Name Common Name Family Rare n Acmispon wrangelianus California deervetch FABACEAE v n ❀ Acourtia microcephala sacapelote ASTERACEAE o n ❀ Adelinia grandis Pacific hound's tongue BORAGINACEAE v n ❀ Adenostoma fasciculatum var. chamise ROSACEAE o fasciculatum n Adiantum jordanii California maidenhair fern PTERIDACEAE o n Agastache urticifolia nettle-leaved horsemint LAMIACEAE v n ❀ Agoseris grandiflora var. grandiflora large-flowered mountain-dandelion ASTERACEAE v n Agoseris heterophylla var. cryptopleura annual mountain-dandelion ASTERACEAE v n Agoseris heterophylla var. heterophylla annual mountain-dandelion ASTERACEAE o i Aira caryophyllea silver hairgrass POACEAE o n Allium fimbriatum var. -

(Cichorium Endivia, L.) Phenolic Extracts on Breast Cancer Cell Line: MCF7

E3 Journal of Biotechnology and Pharmaceutical Research Vol. 3(4), pp. 74-82, June 2012 Available online at http://www.e3journals.org/JBPR ISSN 2141-7474 © 2012 E3 Journals Full Length Research Paper Molecular and biochemical evaluation of anti- proliferative effect of (Cichorium endivia, L.) phenolic extracts on breast cancer cell line: MCF7 Ali Alshehri1* and Hafez E. Elsayed2 1King Khalid University, Faculty of Science, Department of Biology, Abha, Saudi Arabia. 2City for Scientific Research and Technology Applications, Alexandria, Egypt. Accepted 11 May, 2012 Medicinal plants are considered to be the most hopeful way for cancer treatment. The Cichorium endivia, L. plant materials were collected from Tanuma, Saudi Arabia. Methanol extraction for the phenolic compounds was carried out and the HPLC analysis showed that, the extract containing four main compounds with different concentrations. The anticancer activity of the root extract was examined on breast cancer cell line MFC7 compared with the anticancer 5 FU (5-fluorouracil). Cytotoxicity of the root extract against the MFC7 line was 401ug/mL but it was 0.67 ug/mL with the 5 FU. The gene expression for the DNA cancer markers; P53, Bcl2, TNF and interleukin IL-4, IL-6 and IL-2 were examined using real time PCR. The expression of the P53 and TNF was high both in cells treated with FU and root extract. Expression of Bcl2 was high in the cell line treated with root extract compared with the FU, yet this expression still was low compared with the control ones. The expression level of IL-2, IL-4 decreased in the examined cell lines treated with both root extract and with 5FU as well. -

The Vascular Flora of Rarău Massif (Eastern Carpathians, Romania). Note Ii

Memoirs of the Scientific Sections of the Romanian Academy Tome XXXVI, 2013 BIOLOGY THE VASCULAR FLORA OF RARĂU MASSIF (EASTERN CARPATHIANS, ROMANIA). NOTE II ADRIAN OPREA1 and CULIŢĂ SÎRBU2 1 “Anastasie Fătu” Botanical Garden, Str. Dumbrava Roşie, nr. 7-9, 700522–Iaşi, Romania 2 University of Agricultural Sciences and Veterinary Medicine Iaşi, Faculty of Agriculture, Str. Mihail Sadoveanu, nr. 3, 700490–Iaşi, Romania Corresponding author: [email protected] This second part of the paper about the vascular flora of Rarău Massif listed approximately half of the whole number of the species registered by the authors in their field trips or already included in literature on the same area. Other taxa have been added to the initial list of plants, so that, the total number of taxa registered by the authors in Rarău Massif amount to 1443 taxa (1133 species and 310 subspecies, varieties and forms). There was signaled out the alien taxa on the surveyed area (18 species) and those dubious presence of some taxa for the same area (17 species). Also, there were listed all the vascular plants, protected by various laws or regulations, both internal or international, existing in Rarău (i.e. 189 taxa). Finally, there has been assessed the degree of wild flora conservation, using several indicators introduced in literature by Nowak, as they are: conservation indicator (C), threat conservation indicator) (CK), sozophytisation indicator (W), and conservation effectiveness indicator (E). Key words: Vascular flora, Rarău Massif, Romania, conservation indicators. 1. INTRODUCTION A comprehensive analysis of Rarău flora, in terms of plant diversity, taxonomic structure, biological, ecological and phytogeographic characteristics, as well as in terms of the richness in endemics, relict or threatened plant species was published in our previous note (see Oprea & Sîrbu 2012). -

Syrphidae of Southern Illinois: Diversity, Floral Associations, and Preliminary Assessment of Their Efficacy As Pollinators

Biodiversity Data Journal 8: e57331 doi: 10.3897/BDJ.8.e57331 Research Article Syrphidae of Southern Illinois: Diversity, floral associations, and preliminary assessment of their efficacy as pollinators Jacob L Chisausky‡, Nathan M Soley§,‡, Leila Kassim ‡, Casey J Bryan‡, Gil Felipe Gonçalves Miranda|, Karla L Gage ¶,‡, Sedonia D Sipes‡ ‡ Southern Illinois University Carbondale, School of Biological Sciences, Carbondale, IL, United States of America § Iowa State University, Department of Ecology, Evolution, and Organismal Biology, Ames, IA, United States of America | Canadian National Collection of Insects, Arachnids and Nematodes, Ottawa, Canada ¶ Southern Illinois University Carbondale, College of Agricultural Sciences, Carbondale, IL, United States of America Corresponding author: Jacob L Chisausky ([email protected]) Academic editor: Torsten Dikow Received: 06 Aug 2020 | Accepted: 23 Sep 2020 | Published: 29 Oct 2020 Citation: Chisausky JL, Soley NM, Kassim L, Bryan CJ, Miranda GFG, Gage KL, Sipes SD (2020) Syrphidae of Southern Illinois: Diversity, floral associations, and preliminary assessment of their efficacy as pollinators. Biodiversity Data Journal 8: e57331. https://doi.org/10.3897/BDJ.8.e57331 Abstract Syrphid flies (Diptera: Syrphidae) are a cosmopolitan group of flower-visiting insects, though their diversity and importance as pollinators is understudied and often unappreciated. Data on 1,477 Syrphid occurrences and floral associations from three years of pollinator collection (2017-2019) in the Southern Illinois region of Illinois, United States, are here compiled and analyzed. We collected 69 species in 36 genera off of the flowers of 157 plant species. While a richness of 69 species is greater than most other families of flower-visiting insects in our region, a species accumulation curve and regional species pool estimators suggest that at least 33 species are yet uncollected. -

Establishment of in Vitro Root Culture of Cichorium Endivia Subsp, Pumelum L. –A Multipurpose Medicinal Plant

International Journal of ChemTech Research CODEN(USA): IJCRGG, ISSN: 0974-4290, ISSN(Online):2455-9555 Vol.9, No.12pp 141-149,2016 Establishment of in vitro root culture of Cichorium endivia subsp, pumelum L. –a multipurpose medicinal plant Ahmed Amer1, Mona Ibrahim1, Mohsen Askr2 1Plant Biotechnology Department, National Research Centre, Dokki, Cairo, Egypt. 2 Microbial Biotechnology Department, National Research Centre, Dokki, Cairo, Egypt. Abstract:There is a great interest in the production of biologically active substances from plant origin in today's world. Since chicory roots serve as the major source of valuable secondary metabolites, the aim of this study was to develop an efficient protocol for the in vitro root culture of chicory. Medium supplemented with 0.5mg/l NAA and 1mg/l IBA was found to respond maximum with 91% (leaf), 76% (hypocotyl) and 94% (root) for root induction. The maximum biomass accumulation obtained from leaf, hypocotyl and root derived adventitious culture (4.098g, 3.163g and 4.500g respectively) was obtained on the medium contained 0.5mg/l NAA and 0.8mg/l IBA. While a significant increase in rooting response percentage was recorded for leaf (17%), hypocotyl (15%) and root (8%) cultured on half-strength MS medium compared to that cultured on full-strength MS medium, there was no significant differences recorded for the accumulation of root biomass. There was stimulatory effect of total dark condition on root induction and production in all types of explants. A maximum amount of fresh root biomass (9fold) was produced 6 weeks after culture. Moreover, further analysis showed that inulin obtained from our protocol is closely similar to that obtained from open field cultivation in terms of quality and quantity. -

Federico Selvi a Critical Checklist of the Vascular Flora of Tuscan Maremma

Federico Selvi A critical checklist of the vascular flora of Tuscan Maremma (Grosseto province, Italy) Abstract Selvi, F.: A critical checklist of the vascular flora of Tuscan Maremma (Grosseto province, Italy). — Fl. Medit. 20: 47-139. 2010. — ISSN 1120-4052. The Tuscan Maremma is a historical region of central western Italy of remarkable ecological and landscape value, with a surface of about 4.420 km2 largely corresponding to the province of Grosseto. A critical inventory of the native and naturalized vascular plant species growing in this territory is here presented, based on over twenty years of author's collections and study of relevant herbarium materials and literature. The checklist includes 2.056 species and subspecies (excluding orchid hybrids), of which, however, 49 should be excluded, 67 need confirmation and 15 have most probably desappeared during the last century. Considering the 1.925 con- firmed taxa only, this area is home of about 25% of the Italian flora though representing only 1.5% of the national surface. The main phytogeographical features in terms of life-form distri- bution, chorological types, endemic species and taxa of particular conservation relevance are presented. Species not previously recorded from Tuscany are: Anthoxanthum ovatum Lag., Cardamine amporitana Sennen & Pau, Hieracium glaucinum Jord., H. maranzae (Murr & Zahn) Prain (H. neoplatyphyllum Gottschl.), H. murorum subsp. tenuiflorum (A.-T.) Schinz & R. Keller, H. vasconicum Martrin-Donos, Onobrychis arenaria (Kit.) DC., Typha domingensis (Pers.) Steud., Vicia loiseleurii (M. Bieb) Litv. and the exotic Oenothera speciosa Nutt. Key words: Flora, Phytogeography, Taxonomy, Tuscan Maremma. Introduction Inhabited by man since millennia and cradle of the Etruscan civilization, Maremma is a historical region of central-western Italy that stretches, in its broadest sense, from south- ern Tuscany to northern Latium in the provinces of Pisa, Livorno, Grosseto and Viterbo. -

Field Release of the Hoverfly Cheilosia Urbana (Diptera: Syrphidae)

USDA iiillllllllll United States Department of Field release of the hoverfly Agriculture Cheilosia urbana (Diptera: Marketing and Regulatory Syrphidae) for biological Programs control of invasive Pilosella species hawkweeds (Asteraceae) in the contiguous United States. Environmental Assessment, July 2019 Field release of the hoverfly Cheilosia urbana (Diptera: Syrphidae) for biological control of invasive Pilosella species hawkweeds (Asteraceae) in the contiguous United States. Environmental Assessment, July 2019 Agency Contact: Colin D. Stewart, Assistant Director Pests, Pathogens, and Biocontrol Permits Plant Protection and Quarantine Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service U.S. Department of Agriculture 4700 River Rd., Unit 133 Riverdale, MD 20737 Non-Discrimination Policy The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination against its customers, employees, and applicants for employment on the bases of race, color, national origin, age, disability, sex, gender identity, religion, reprisal, and where applicable, political beliefs, marital status, familial or parental status, sexual orientation, or all or part of an individual's income is derived from any public assistance program, or protected genetic information in employment or in any program or activity conducted or funded by the Department. (Not all prohibited bases will apply to all programs and/or employment activities.) To File an Employment Complaint If you wish to file an employment complaint, you must contact your agency's EEO Counselor (PDF) within 45 days of the date of the alleged discriminatory act, event, or in the case of a personnel action. Additional information can be found online at http://www.ascr.usda.gov/complaint_filing_file.html. To File a Program Complaint If you wish to file a Civil Rights program complaint of discrimination, complete the USDA Program Discrimination Complaint Form (PDF), found online at http://www.ascr.usda.gov/complaint_filing_cust.html, or at any USDA office, or call (866) 632-9992 to request the form.