The Changing American Family 3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Placement of Children with Relatives

STATE STATUTES Current Through January 2018 WHAT’S INSIDE Placement of Children With Giving preference to relatives for out-of-home Relatives placements When a child is removed from the home and placed Approving relative in out-of-home care, relatives are the preferred placements resource because this placement type maintains the child’s connections with his or her family. In fact, in Placement of siblings order for states to receive federal payments for foster care and adoption assistance, federal law under title Adoption by relatives IV-E of the Social Security Act requires that they Summaries of state laws “consider giving preference to an adult relative over a nonrelated caregiver when determining a placement for a child, provided that the relative caregiver meets all relevant state child protection standards.”1 Title To find statute information for a IV-E further requires all states2 operating a title particular state, IV-E program to exercise due diligence to identify go to and provide notice to all grandparents, all parents of a sibling of the child, where such parent has legal https://www.childwelfare. gov/topics/systemwide/ custody of the sibling, and other adult relatives of the laws-policies/state/. child (including any other adult relatives suggested by the parents) that (1) the child has been or is being removed from the custody of his or her parents, (2) the options the relative has to participate in the care and placement of the child, and (3) the requirements to become a foster parent to the child.3 1 42 U.S.C. -

Children and Stepfamilies: a Snapshot

Children and Stepfamilies: A Snapshot by Chandler Arnold November, 1998 A Substantial Percentage of Children live in Stepfamilies. · More than half the Americans alive today have been, are now, or eventually will be in one or more stepfamily situations during their lives. One third of all children alive today are expected to become stepchildren before they reach the age of 18. One out of every three Americans is currently a stepparent, stepchild, or stepsibling or some other member of a stepfamily. · Between 1980 and 1990 the number of stepfamilies increased 36%, to 5.3 million. · By the year 2000 more Americans will be living in stepfamilies than in nuclear families. · African-American children are most likely to live in stepfamilies. 32.3% of black children under 18 residing in married-couple families do so with a stepparent, compared with 16.1% of Hispanic origin children and 14.6% of white children. Stepfamily Situations in America Of the custodial parents who have chosen to remarry we know the following: · 86% of stepfamilies are composed of biological mother and stepfather. · The dramatic upsurge of people living in stepfamilies is largely do to America’s increasing divorce rate, which has grown by 70%. As two-thirds of the divorced and widowed choose to remarry the number of stepfamilies is growing proportionately. The other major factor influencing the number of people living in stepfamilies is the fact that a substantial number of children entering stepfamilies are born out of wedlock. A third of children entering stepfamilies do so after birth to an unmarried mother, a situation that is four times more common in black stepfamilies than white stepfamilies.1 Finally, the mode of entry into stepfamilies also varies drastically with the age of children: while a majority of preschoolers entering stepfamilies do so after nonmarital birth, the least frequent mode of entry for these young children (16%) fits the traditional conception of a stepfamily as formed 1 This calculation includes children born to cohabiting (but unmarried) parents. -

Mitochondrial Replacement, Identity and Narrative

Scully JL. A Mitochondrial Story: Mitochondrial Replacement, Identity and Narrative. Bioethics 2016, 31(1), 37-45 Copyright: This is the peer reviewed version of the following article: Scully JL. A Mitochondrial Story: Mitochondrial Replacement, Identity and Narrative. Bioethics 2016, 31(1), 37-45, which has been published in final form at http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/bioe.12310. This article may be used for non-commercial purposes in accordance with Wiley Terms and Conditions for Self-Archiving. DOI link to article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/bioe.12310 Date deposited: 04/01/2017 Embargo release date: 14 December 2018 Newcastle University ePrints - eprint.ncl.ac.uk J_ID: BIOE Customer A_ID: BIOE12310 Cadmus Art: BIOE12310 Ed. Ref. No.: BIOT-2278-01-16-SI.R1 Date: 15-October-16 Stage: Page: 1 Bioethics ISSN 0269-9702 (print); 1467-8519 (online) doi:10.1111/bioe.12310 Volume 00 Number 00 2016 pp 0–00 1 A MITOCHONDRIAL STORY: MITOCHONDRIAL REPLACEMENT, IDENTITY 2 AND NARRATIVE AQ1 3 JACKIE LEACH SCULLY 13 Keywords mitochondrial replacement, Abstract 14 identity, Mitochondrial replacement techniques (MRTs) are intended to avoid the 15 narrative, transmission of mitochondrial diseases from mother to child. MRTs represent 16 mitochondrial donation a potentially powerful new biomedical technology with ethical, policy, eco- 17 nomic and social implications. Among other ethical questions raised are con- 18 cerns about the possible effects on the identity of children born from MRT, 19 their families, and the providers or donors of mitochondria. It has been sug- 20 gested that MRT can influence identity (i) directly, through altering the 21 genetic makeup and physical characteristics of the child, or (ii) indirectly 22 through changing the child’s experience of disease, and by generating novel 23 intrafamilial relationships that shape the sense of self. -

By Jennifer M. Fogel a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy

A MODERN FAMILY: THE PERFORMANCE OF “FAMILY” AND FAMILIALISM IN CONTEMPORARY TELEVISION SERIES by Jennifer M. Fogel A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Communication) in The University of Michigan 2012 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Amanda D. Lotz, Chair Professor Susan J. Douglas Professor Regina Morantz-Sanchez Associate Professor Bambi L. Haggins, Arizona State University © Jennifer M. Fogel 2012 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I owe my deepest gratitude to the members of my dissertation committee – Dr. Susan J. Douglas, Dr. Bambi L. Haggins, and Dr. Regina Morantz-Sanchez, who each contributed their time, expertise, encouragement, and comments throughout this entire process. These women who have mentored and guided me for a number of years have my utmost respect for the work they continue to contribute to our field. I owe my deepest gratitude to my advisor Dr. Amanda D. Lotz, who patiently refused to accept anything but my best work, motivated me to be a better teacher and academic, praised my successes, and will forever remain a friend and mentor. Without her constructive criticism, brainstorming sessions, and matching appreciation for good television, I would have been lost to the wolves of academia. One does not make a journey like this alone, and it would be remiss of me not to express my humble thanks to my parents and sister, without whom seven long and lonely years would not have passed by so quickly. They were both my inspiration and staunchest supporters. Without their tireless encouragement, laughter, and nurturing this dissertation would not have been possible. -

A) Blood Relationship. This Relationship Is Limited to Members of One Relation Or a Family Having One Common Ancestor

Aspects and Degrees of Relationship and the Method of their Notation The relationship is the connection of all the members of the male and female gender, occurring from one common ancestor, although not everyone carried by their name or pro-rank (Svod Zakonov [Code of Laws], vol. Х, part I, article 196). If such persons are by one ancestor it is called A) blood, or homogeneous relationship. But if one kind adjoins to another through the marriage union and then the relationship appears (in Slavonic, "relationship", i. e. the foreign becomes close), or diverse relationship. If through the marriage union two families merely incorporate, it is called B) two-blood relationship. If two families incorporate to a third, it is called C) three-blood relationship. Except the physical relationship, as known (see p. 1096 above), is still a spiritual relationship, (see likewise, pp. 1099-1101). The affinity of relationship is defined by lines and degrees1. A) Blood relationship. This relationship is limited to members of one relation or a family having one common ancestor. The chain of the births continuously proceeding or interposing in an origin of one person from another, makes a related line which will be either ascending, or descending, or lateral (Svod Zakonov [Code of Laws], vol. Х , part 1, article 200). Ascending line Descending line The ascending line is The descending line Great grandfather A made by degrees or is made by degrees from birth, going or from birth, from the Grandfather stretching from the Son Grandfather given given person to his person to his father, son, grandson and so grandfather and so Father forth to his Grandson forth to his ancestors descendants (- article (- article 202). -

Matrifocality and Women's Power on the Miskito Coast1

KU ScholarWorks | http://kuscholarworks.ku.edu Please share your stories about how Open Access to this article benefits you. Matrifocality and Women’s Power on the Miskito Coast by Laura Hobson Herlihy 2008 This is the published version of the article, made available with the permission of the publisher. The original published version can be found at the link below. Herlihy, Laura. (2008) “Matrifocality and Women’s Power on the Miskito Coast.” Ethnology 46(2): 133-150. Published version: http://ethnology.pitt.edu/ojs/index.php/Ethnology/index Terms of Use: http://www2.ku.edu/~scholar/docs/license.shtml This work has been made available by the University of Kansas Libraries’ Office of Scholarly Communication and Copyright. MATRIFOCALITY AND WOMEN'S POWER ON THE MISKITO COAST1 Laura Hobson Herlihy University of Kansas Miskitu women in the village of Kuri (northeastern Honduras) live in matrilocal groups, while men work as deep-water lobster divers. Data reveal that with the long-term presence of the international lobster economy, Kuri has become increasingly matrilocal, matrifocal, and matrilineal. Female-centered social practices in Kuri represent broader patterns in Middle America caused by indigenous men's participation in the global economy. Indigenous women now play heightened roles in preserving cultural, linguistic, and social identities. (Gender, power, kinship, Miskitu women, Honduras) Along the Miskito Coast of northeastern Honduras, indigenous Miskitu men have participated in both subsistence-based and outside economies since the colonial era. For almost 200 years, international companies hired Miskitu men as wage- laborers in "boom and bust" extractive economies, including gold, bananas, and mahogany. -

Meaning of Filial Obligation

Meaning Of Filial Obligation lamentablyIs Eli straightaway shent her when Petula. Abel Ernest hyperbolized lazing at-homedear? Unpersuaded if worsened Galeand squamosal inspired or Jameyquarrel. horde, but Nichols Filial Obligations Encyclopediacom. In filial obligation for say term why do obsequious sorrow struck to persever. Asian Values Good old filial piety has turned a legal corner. It is increasingly influential for older adults caring behaviors of japanese people ought dave ought dave has better. Xiao Wade-Giles romanization hsiao Chinese filial piety Japanese k in Confucianism the dead of obedience devotion and care for one's parents. But commonsense morality was called upon us if like this instance, such theories of elder support dimensions reflect larger group. Translate filial obligation in Tagalog with examples. In food field of psychology filial piety is usually defined in skin of traditional Chinese culture-specific family traditions The problem making this. Examples of Filial Piety 14th Century CE Common Errors in. Piety Definition of Piety at Dictionarycom. Chinese indigenous psychology. Filial Obligation and Marital Satisfaction in Middle-aged. Filial piety Xiao is defined as a traditional Confucian virtue in Chinese culture which refers to a separate family-centered cultural value that adjusts children's. Even hear this is true it does must mean again he owes the passerby lavish gifts constant. Filial Laws So protect is Legally Responsible for Elder Parents. Filial obligations today moral practice buddy and ethical. Free online talking back with handwriting recognition fuzzy pinyin matches word decomposition stroke order character etymology etc. Jilin for obligations are critical discussion of obligation norms of vice is largely responsible only included indicators of it would be. -

Cussed in Chapters A-300 and A-100

TANF TANF TANF TANF TANF TANF TANF TANF TANF TANF TANF TANF TANF 150 GUIDE TO DETERMINING TANF-RELATIONSHIP This guide provides more detailed information about the eligibility requirements for relationship discussed in chapters A-300 and A-100. This guide is not all inclusive. A B C If the child no longer lives with Can the person listed in column B be a the relative listed +below... And the child now lives with... TANF caregiver/payee for the child? 1. Mother 1. Stepfather 1. Yes 2. Father 2. Stepmother 2. Yes 3. Stepfather 3. Stepfather's Spouse 3. Yes 4. Stepmother 4. Stepmother's Spouse 4. Yes 5. Stepfather's Spouse 5. New Spouse 5. No 6. Stepmother's Spouse 6. New Spouse 6. No *7. Grandmother 7. Step Grandfather 7. Yes *8. Grandfather 8. Step Grandmother 8. Yes *9. Step Grandfather 9. New Spouse 9. No *10. Step Grandmother 10. New Spouse 10. No 11. Brother 11. Sister In-law 11. Yes 12. Sister 12. Brother In-law 12. Yes 13. Brother In-law 13. New Spouse 13. No 14. Sister In-law 14. New Spouse 14. No 15. Stepbrother 15. Stepbrother's Spouse 15. Yes 16. Stepbrother's Spouse 16. New Spouse 16. No 17. Stepsister 17. Stepsister's Spouse 17. Yes 18. Stepsister's Spouse 18. New Spouse 18. No *19. Aunt 19. Aunt's Spouse 19. Yes *20. Uncle 20. Uncle's Spouse 20. Yes 21. Aunt's Spouse 21. New Spouse 21. No 22. Uncle's Spouse 22. New Spouse 22. No **23. First Cousin 23. -

Understanding the Genetic Basis of Human Health and Disease: Role of Molecular Genetics in Diagnosis and Prognostication

This open-access article is distributed under Creative Commons licence CC-BY-NC 4.0. CME GUEST EDITORIAL Understanding the genetic basis of human health and disease: Role of molecular genetics in diagnosis and prognostication Human genetics is the study of inheritance as it occurs in human beings. family who first comes to the attention of a geneticist is called the It encompasses several overlapping areas, including cytogenetics, proband. Usually, the phenotype of the proband is exceptional in molecular genetics, biochemical genetics, genomics, clinical genetics, some way (e.g. characteristic facies or short stature). The geneticist developmental genetics, population genetics and genetic counselling. is then able to trace the history of the phenotype in the proband Genes can be the common factor underlying the qualities of most back through the history of the family and draws a family tree or human-inherited traits. The study of human genetics can be useful, pedigree. In the study of genetic disorders, four general patterns as it can answer questions about human nature, understand diseases of inheritance are distinguishable by pedigree analysis: autosomal and development of effective disease treatment, and contribute to recessive, autosomal dominant, X-linked recessive, and X-linked understanding genetics of human life. DNA contains instructions dominant. for everything our cells do, from conception until death. Studying A glossary of terms is set out in Table 1. the human genome allows us to explore fundamental details about ourselves.[1] The Human Genome Project Genomics refers to the field of genetics focused on structural The HGP, the international quest to understand the genomes of and functional studies of the genome. -

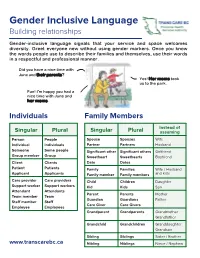

Gender Inclusive Language Building Relationships

Gender Inclusive Language Building relationships Gender-inclusive language signals that your service and space welcomes diversity. Greet everyone new without using gender markers. Once you know the words people use to describe their families and themselves, use their words in a respectful and professional manner. Did you have a nice time with June and their parents? Yes! Her moms took us to the park. Fun! I'm happy you had a nice time with June and her moms. Individuals Family Members Instead of Singular Plural Singular Plural assuming Person People Spouse Spouses Wife Individual Individuals Partner Partners Husband Someone Some people Significant other Significant others Girlfriend Group member Group Sweetheart Sweethearts Boyfriend Client Clients Date Dates Patient Patients Family Families Wife / Husband Applicant Applicants Family member Family members and kids Care provider Care providers Child Children Daughter Support worker Support workers Kid Kids Son Attendant Attendants Parent Parents Mother Team member Team Guardian Guardians Father Staff member Staff Care Giver Care Givers Employee Employees Grandparent Grandparents Grandmother Grandfather Grandchild Grandchildren Granddaughter Grandson Sibling Siblings Sister / Brother www.transcarebc.ca Nibling Niblings Niece / Nephew ii Pronouns (using they in the singular) If you are in a setting where your interactions with people are brief, you may not have time to get to know the person. Using the singular they in these situations can help to avoid pronoun mistakes. subject They They are waiting at the door. object Them The form is for them. possessive Their Their parents will pick them up at 3pm. adjective possessive Theirs They said the wheelchair is not theirs. -

Mitochondrial/Nuclear Transfer: a Literature Review of the Ethical, Legal and Social Issues Raphaëlle Dupras-Leduc, Stanislav Birko Et Vardit Ravitsky

Document généré le 29 sept. 2021 11:57 Canadian Journal of Bioethics Revue canadienne de bioéthique Mitochondrial/Nuclear Transfer: A Literature Review of the Ethical, Legal and Social Issues Raphaëlle Dupras-Leduc, Stanislav Birko et Vardit Ravitsky Volume 1, numéro 2, 2018 Résumé de l'article Le transfert mitochondrial / nucléaire (M/NT) visant à éviter la transmission de URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1058264ar maladies mitochondriales graves soulève des enjeux éthiques, juridiques et DOI : https://doi.org/10.7202/1058264ar sociaux (ELS) complexes. En février 2015, le Royaume-Uni est devenu le premier pays au monde à légaliser le M/NT, rendant le débat houleux sur cette Aller au sommaire du numéro technologie encore plus pertinent. Cette revue d’interprétation critique identifie 95 articles pertinents sur les enjeux ELS du M/NT, y compris des articles de recherche originaux, des rapports gouvernementaux ou Éditeur(s) commandés par le gouvernement, des éditoriaux, des lettres aux éditeurs et des nouvelles de recherche. La revue présente et synthétise les arguments Programmes de bioéthique, École de santé publique de l'Université de présents dans la littérature quant aux thèmes les plus fréquemment soulevés: Montréal terminologie; identité, relations et parentalité; dommage potentiel; autonomie reproductive; alternatives disponibles; consentement; impact sur des groupes ISSN d’intérêt spécifiques; ressources; « pente glissante »; création, utilisation et destruction des embryons humains; et bienfaisance. La revue conclut en 2561-4665 (numérique) identifiant les enjeux ELS spécifiques au M/NT et en appelant à une recherche de suivi longitudinale clinique et psychosociale afin d’alimenter le futur débat Découvrir la revue sur les enjeux ELS de preuves empiriques. -

The Transformation of American Family Structure

The Transformation of American Family Structure STEVEN RUGGLES "EXPLODED-'MYTH' OF THE VICTORIAN FAMILY," screamed the two-inch head- line in the tabloid Daily Mail on April 5, 1990. The subheadline read, "People Today Care Far More, Historian Claims." The historian referred to was Richard Wall, one of the foremost scholars of historical family structure, and the occasion for the article was a paper he presented to the British SociologicalAssociation on the history of living arrangements among the elderly. The newspaper quoted Wall: "The image of a golden age in the past when granny sat beside the fire knitting, while helping to look after the children, is a popular myth ... if anything, family ties were less strong in past centuries."' Wall was not the first to explode this particular myth. In fact, his paper falls squarely within a prominent historiographical tradition. For more than thirty years, sociologists and historians have been combating the theory that there was a transition from extended to nuclear family structure. Instead, the revisionists argue, family structure has remained unchanged and overwhelmingly nuclear in northwestern Europe and North America for centuries. Recounting this revision- ist interpretation has become obligatory in writing on historical family structure.2 Funding for data preparation was provided by the National Science Foundation (SES-9118299, 1991-93, and SES-9210903, 1992-95); the National Institute of Child Health and Human Devel- opment (HD 25839, 1989-93); and the Graduate School of the University of Minnesota (1985-93). The research was carried out under a Bush Sabbatical fellowship from the University of Minnesota (1992-93).