How Monstrosity and Geography Were Used to Define the Other in Early Medieval Europe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Parish Apostolate: New Opportunities in the Local Church

IV. PARISH APOSTOLATE: NEW OPPORTUNITIES IN THE LOCAL CHURCH by John E. Rybolt, C.M. Beginning with the original contract establishing the Community, 17 April 1625, Vincentians have worked in parishes. At fIrst they merely assisted diocesan pastors, but with the foundation at Toul in 1635, the fIrst outside of Paris, they assumed local pastorates. Saint Vincent himself had been the pastor of Clichy-Ia-Garenne near Paris (1612-1625), and briefly (1617) of Buenans and Chatillon les-Dombes in the diocese of Lyons. Later, as superior general, he accepted eight parish foundations for his community. He did so with some misgiving, however, fearing the abandonment of the country poor. A letter of 1653 presents at least part of his outlook: ., .parishes are not our affair. We have very few, as you know, and those that we have have been given to us against our will, or by our founders or by their lordships the bishops, whom we cannot refuse in order not to be on bad terms with them, and perhaps the one in Brial is the last that we will ever accept, because the further along we go, the more we fmd ourselves embarrassed by such matters. l In the same spirit, the early assemblies of the Community insisted that parishes formed an exception to its usual works. The assembly of 1724 states what other Vincentian documents often said: Parishes should not ordinarily be accepted, but they may be accepted on the rare occasions when the superior general .. , [and] his consul tors judge it expedient in the Lord.2 229 Beginnings to 1830 The founding document of the Community's mission in the United States signed by Bishop Louis Dubourg, Fathers Domenico Sicardi and Felix De Andreis, spells out their attitude toward parishes in the new world, an attitude differing in some respects from that of the 1724 assembly. -

1. from the Beginnings to 1000 Ce

1. From the Beginnings to 1000 ce As the history of French wine was beginning, about twenty-five hundred years ago, both of the key elements were missing: there was no geographi- cal or political entity called France, and no wine was made on the territory that was to become France. As far as we know, the Celtic populations living there did not produce wine from any of the varieties of grapes that grew wild in many parts of their land, although they might well have eaten them fresh. They did cultivate barley, wheat, and other cereals to ferment into beer, which they drank, along with water, as part of their daily diet. They also fermented honey (for mead) and perhaps other produce. In cultural terms it was a far cry from the nineteenth century, when France had assumed a national identity and wine was not only integral to notions of French culture and civilization but held up as one of the impor- tant influences on the character of the French and the success of their nation. Two and a half thousand years before that, the arbiters of culture and civilization were Greece and Rome, and they looked upon beer- drinking peoples, such as the Celts of ancient France, as barbarians. Wine was part of the commercial and civilizing missions of the Greeks and Romans, who introduced it to their new colonies and later planted vine- yards in them. When they and the Etruscans brought wine and viticulture to the Celts of ancient France, they began the history of French wine. -

June 2021 E-Newsletter

This month marks the beginning of summer in Minnesota. June 20 is the summer solstice, when our planet is tilted so that the Sun shines on its northernmost point on Earth, the imaginary line known as the Tropic of Cancer, about 23° latitude north of the equator. We have longer hours of daylight than on any other day of the year. It is as if the northern hemisphere of the Earth has turned its face toward the Sun, welcoming its warmth and shining light. Certain plants and flowers also have a rhythm of turning toward the Sun, a phenomenon known as heliotropism. In the morning, young sunflowers are turned toward the east, anticipating the sunrise. Throughout the day, they follow the path the Sun traces in the sky, continually re-orienting and turning themselves toward the Sun’s shining light and warmth until sunset in the west. By constantly following the Sun, the young sunflower collects more energy for growing. If the Earth and even flowers turn toward the Sun, to whom do we turn? Saint Field of sunflowers facing the sun Benedict encourages us to open our eyes to the light that comes from God (Rule of Benedict, Prologue: 9). Imagine for a moment how you feel when you stand in a sunbeam, soaking in the warmth. “Look toward God and be radiant” (Paraphrase of Psalm 34:5). Benedictines strive to live the promise of conversatio, which is a constant turning of our hearts away from ourselves and towards God. This promise is our seeking to remain within God’s light in all that we say and do, and in all our being. -

Complicated Meckel's Diverticulum and Therapeutic Management

Ulusal Cer Derg 2013; 29: 63-66 Original Investigation DOI: 10.5152/UCD.2013.36 Complicated Meckel's diverticulum and therapeutic management Varlık Erol, Tayfun Yoldaş, Samet Cin, Cemil Çalışkan, Erhan Akgün, Mustafa Korkut Objective: This study aimed to investigate the treatment options and compare patient management with the litera- ABSTRACT ture for patients operated on for an acute abdomen who had complications due to inflammation of the Meckel’s diverticulum at our clinics. Material and Methods: This study retrospectively evaluated 14 patients who had been operated on for acute abdo- men and had been diagnosed with Meckel’s diverticulitis (MD) in Ege University Medical Faculty Department of General Surgery, between October 2007 and October 2012. Results: Fourteen patients with a diagnosis of Meckel’s diverticulitis (MD) were retrospectively analyzed. Radiologi- cally, the abdominal computer tomography showed pathologies compatible with mechanical intestinal obstruction, Meckel’s diverticulitis and peridiverticular abscess, as well as detection of free air within the abdomen on direct abdominal X-ray. Among patients diagnosed with complicated Meckel’s diverticuli (obstruction, diverticulitis, perfo- ration) 10 patients had partial small bowel resection and end-to-end anastomosis (71.5%), three patients underwent diverticulum excision (21.4%), and one patient underwent right hemicolectomy+ileotransversostomy (7.1%). Conclusion: Meckel’s diverticulum is a vestigial remnant of an omphalomesenteric channel in the small bowel. It is a real congenital diverticular abnormality that contains all three layers of the small bowel. Surgical excision should be performed if Meckel’s diverticulum is detected in order to avoid incidental complications such as ulcer- ation, bleeding, bowel obstruction, diverticulitis or perforation. -

JUDITH MERRIL-PDF-Sep23-07.Pdf (368.7Kb)

JUDITH MERRIL: AN ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY AND GUIDE Compiled by Elizabeth Cummins Department of English and Technical Communication University of Missouri-Rolla Rolla, MO 65409-0560 College Station, TX The Center for the Bibliography of Science Fiction and Fantasy December 2006 Table of Contents Preface Judith Merril Chronology A. Books B. Short Fiction C. Nonfiction D. Poetry E. Other Media F. Editorial Credits G. Secondary Sources About Elizabeth Cummins PREFACE Scope and Purpose This Judith Merril bibliography includes both primary and secondary works, arranged in categories that are suitable for her career and that are, generally, common to the other bibliographies in the Center for Bibliographic Studies in Science Fiction. Works by Merril include a variety of types and modes—pieces she wrote at Morris High School in the Bronx, newsletters and fanzines she edited; sports, westerns, and detective fiction and non-fiction published in pulp magazines up to 1950; science fiction stories, novellas, and novels; book reviews; critical essays; edited anthologies; and both audio and video recordings of her fiction and non-fiction. Works about Merill cover over six decades, beginning shortly after her first science fiction story appeared (1948) and continuing after her death (1997), and in several modes— biography, news, critical commentary, tribute, visual and audio records. This new online bibliography updates and expands the primary bibliography I published in 2001 (Elizabeth Cummins, “Bibliography of Works by Judith Merril,” Extrapolation, vol. 42, 2001). It also adds a secondary bibliography. However, the reasons for producing a research- based Merril bibliography have been the same for both publications. Published bibliographies of Merril’s work have been incomplete and often inaccurate. -

The Cambridge Companion to Age of Constantine.Pdf

The Cambridge Companion to THE AGE OF CONSTANTINE S The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Constantine offers students a com- prehensive one-volume introduction to this pivotal emperor and his times. Richly illustrated and designed as a readable survey accessible to all audiences, it also achieves a level of scholarly sophistication and a freshness of interpretation that will be welcomed by the experts. The volume is divided into five sections that examine political history, reli- gion, social and economic history, art, and foreign relations during the reign of Constantine, a ruler who gains in importance because he steered the Roman Empire on a course parallel with his own personal develop- ment. Each chapter examines the intimate interplay between emperor and empire and between a powerful personality and his world. Collec- tively, the chapters show how both were mutually affected in ways that shaped the world of late antiquity and even affect our own world today. Noel Lenski is Associate Professor of Classics at the University of Colorado, Boulder. A specialist in the history of late antiquity, he is the author of numerous articles on military, political, cultural, and social history and the monograph Failure of Empire: Valens and the Roman State in the Fourth Century ad. Cambridge Collections Online © Cambridge University Press, 2007 Cambridge Collections Online © Cambridge University Press, 2007 The Cambridge Companion to THE AGE OF CONSTANTINE S Edited by Noel Lenski University of Colorado Cambridge Collections Online © Cambridge University Press, 2007 cambridge university press Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, Sao˜ Paulo Cambridge University Press 40 West 20th Street, New York, ny 10011-4211, usa www.cambridge.org Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9780521818384 c Cambridge University Press 2006 This publication is in copyright. -

Black Cosmopolitans

BLACK COSMOPOLITANS BLACK COSMOPOLITANS Race, Religion, and Republicanism in an Age of Revolution Christine Levecq university of virginia press Charlottesville and London University of Virginia Press © 2019 by the Rector and Visitors of the University of Virginia All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper First published 2019 ISBN 978-0-8139-4218-6 (cloth) ISBN 978-0-8139-4219-3 (e-book) 1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2 Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data is available for this title. Cover art: Jean-Baptiste Belley. Portrait by Anne Louis Girodet de Roussy- Trioson, 1797, oil on canvas. (Château de Versailles, France) To Steve and Angie CONTENTS Acknowledgments ix Introduction 1 1. Jacobus Capitein and the Radical Possibilities of Calvinism 19 2. Jean- Baptiste Belley and French Republicanism 75 3. John Marrant: From Methodism to Freemasonry 160 Notes 237 Works Cited 263 Index 281 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This book has been ten years in the making. One reason is that I wanted to explore the African diaspora more broadly than I had before, and my knowledge of English, French, and Dutch naturally led me to expand my research to several national contexts. Another is that I wanted this project to be interdisciplinary, combining history and biography with textual criticism. It has been an amazing journey, which was made pos- sible by the many excellent scholars this book relies on. Part of the pleasure in writing this book came from the people and institutions that provided access to both the primary and the second- ary material. -

Joseph Hippolyte Cloquet

Article Clinical & Translational Neuroscience January–June 2018: 1–10 ª The Author(s) 2018 Joseph Hippolyte Cloquet (1787–1840)— Reprints and permissions: sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav DOI: 10.1177/2514183X17738406 Physiology of smell: Portrait of a pioneer journals.sagepub.com/home/ctn Olivier Walusinski1 Abstract While the physiology, histology and stem cell biology of smell are active fields of contemporary research, smell is probably the sense that physicians knew the least about prior to the 20th century. Joseph-Hippolyte Cloquet (1787–1840) was an anatomist who, in 1815, defended a singular doctoral thesis—On odours, the sense of olfaction and the olfactory organs—then went on to publish, in 1821, the first complete treatise on rhinology. In our biographical sketch, we focus on Cloquet’s significant contributions to olfactory anatomy and physiology. His realization that odours are chemical and molecular in nature led him to formulate an accurate functional theory of the olfactory mucosa. Following a historical introduction, we review contemporary literature on the anatomical–functional understanding of olfaction and propose a (possibly deba- table) theory for the lexical deficits one encounters when trying to describe the sense of smell. Keywords Neurophysiology of olfaction, history of neurology, cloquet, smell, language ‘Olfaction can be seen at every turn of the labyrinth’. To olfactory nerve is the first pair of nerves that leave the skull explain the purpose of his doctoral thesis, Joseph Hippolyte and project to the olfactory mucosa. It has a great number of Cloquet (1787–1840) (Figure 1) used this clever expres- nervous filaments’. Le Cat, like all philosophers, took an sion, thereby linking three of our five senses: sight, smell interest in perception (our interactions with objects and the and hearing. -

Arianism and Political Power in the Vandal and Ostrogothic Kingdoms

Western Washington University Western CEDAR WWU Graduate School Collection WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship 2012 Reign of heretics: Arianism and political power in the Vandal and Ostrogothic kingdoms Christopher J. (Christopher James) Nofziger Western Washington University Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwuet Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Nofziger, Christopher J. (Christopher James), "Reign of heretics: Arianism and political power in the Vandal and Ostrogothic kingdoms" (2012). WWU Graduate School Collection. 244. https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwuet/244 This Masters Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in WWU Graduate School Collection by an authorized administrator of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Reign of Heretics: Arianism and Political Power in the Vandal and Ostrogothic Kingdoms By Christopher James Nofziger Accepted in Partial Completion Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts Kathleen L. Kitto, Dean of the Graduate School Advisory Committee Chair, Dr. Peter Diehl Dr. Amanda Eurich Dr. Sean Murphy MASTER’S THESIS In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a master’s degree at Western Washington University, I grant to Western Washington University the non- exclusive royalty-free right to archive, reproduce, and display the thesis in any and all forms, including electronic format, via any digital library mechanisms maintained by WWU. I represent and warrant this is my original work, and does not infringe or violate any rights of others. I warrant that I have obtained written permissions from the owner of any third party copyrighted material included in these files. -

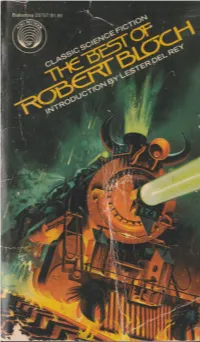

Bloch the Best of Edmond Hamilton Introduction by Leigh Brackett the Best of Leigh Brackett Introduction by Edmond Hamilton *The Best of L

THE STALKING DEAD The lights went out. Somebody giggled. I heard footsteps in the darkness. Mutter- ings. A hand brushed my face. Absurd, standing here in the dark with a group of tipsy fools, egged on by an obsessed Englishman. And yet there was real terror here . Jack the Ripper had prowled in dark ness like this, with a knife, a madman's brain and a madman's purpose. But Jack the Ripper was dead and dust these many years—by every human law . Hollis shrieked; there was a grisly thud. The lights went on. Everybody screamed. Sir Guy Hollis lay sprawled on the floor in the center of the room—Hollis, who had moments before told of his crack-brained belief that the Ripper still stalked the earth . The Critically Acclaimed Series of Classic Science Fiction NOW AVAILABLE: The Best of Stanley G. Weinbaum Introduction by Isaac Asimov The Best of Fritz Leiber Introduction by Poul Anderson The Best of Frederik Pohl Introduction by Lester del Rey The Best of Henry Kuttne'r Introduction by Ray Bradbury The Best of Cordwainer Smith Introduction by J. J. Pierce The Best of C. L. Moore Introduction by Lester del Rey The Best of John W. Campbell Introduction by Lester del Rey The Best of C. M. Kornbluth Introduction by Frederik Pohl The Best of Philip K. Dick Introduction by John Brunner The Best of Fredric Brown Introduction by Robert Bloch The Best of Edmond Hamilton Introduction by Leigh Brackett The Best of Leigh Brackett Introduction by Edmond Hamilton *The Best of L. -

The Emergence of Archival Records at Rome in the Fourth Century BCE

Foundations of History: The Emergence of Archival Records at Rome in the Fourth Century BCE by Zachary B. Hallock A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Greek and Roman History) in the University of Michigan 2018 Doctoral Committee: Professor David Potter, Chair Associate Professor Benjamin Fortson Assistant Professor Brendan Haug Professor Nicola Terrenato Zachary B. Hallock [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0003-0337-0181 © 2018 by Zachary B. Hallock To my parents for their endless love and support ii Acknowledgements I would like to thank Rackham Graduate School and the Departments of Classics and History for providing me with the resources and support that made my time as a graduate student comfortable and enjoyable. I would also like to express my gratitude to the professors of these departments who made themselves and their expertise abundantly available. Their mentoring and guidance proved invaluable and have shaped my approach to solving the problems of the past. I am an immensely better thinker and teacher through their efforts. I would also like to express my appreciation to my committee, whose diligence and attention made this project possible. I will be forever in their debt for the time they committed to reading and discussing my work. I would particularly like to thank my chair, David Potter, who has acted as a mentor and guide throughout my time at Michigan and has had the greatest role in making me the scholar that I am today. Finally, I would like to thank my wife, Andrea, who has been and will always be my greatest interlocutor. -

Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection

Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection 2016–2017 Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection Annual Report 2016–2017 © 2017 Dumbarton Oaks Trustees for Harvard University, Washington, D.C. ISSN 0197-9159 Cover photograph: The Byzantine Courtyard for the reopening of the museum in April 2017. Frontispiece: The Music Room after the installation of new LED lighting. www.doaks.org/about/annual-reports Contents From the Director 7 Director’s Office 13 Academic Programs 19 Fellowship Reports 35 Byzantine Studies 59 Garden and Landscape Studies 69 Pre-Columbian Studies 85 Library 93 Publications 99 Museum 113 Gardens 121 Friends of Music 125 Facilities, Finance, Human Resources, and Information Technology 129 Administration and Staff 135 From the Director A Year of Collaboration Even just within the walls and fencing of our sixteen acres, too much has happened over the past year for a full accounting. Attempting to cover all twelve months would be hopeless. Instead, a couple of happenings in May exemplify the trajectory on which Dumbarton Oaks is hurtling forward and upward. The place was founded for advanced research. No one who respects strong and solid tradi- tions would wrench it from the scholarship enshrined in its library, archives, and research collections; at the same time, it was designed to welcome a larger public. These two events give tribute to this broader engagement. To serve the greater good, Dumbarton Oaks now cooperates vigorously with local schools. It is electrifying to watch postdoc- toral and postgraduate fellows help students enjoy and learn from our gardens and museum collections. On May 16, we hosted a gath- ering with delegates from the DC Collaborative.