Metaphor, Analogy and the Brain in the Work of Thomas Willis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

History of Physics Group Newsletter No 21 January 2007

History of Physics Group Newsletter No 21 January 2007 Cover picture: Ludwig Boltzmann’s ‘Bicykel’ – a piece of apparatus designed by Boltzmann to demonstrate the effect of one electric circuit on another. This, and the picture of Boltzmann on page 27, are both reproduced by kind permission of Dr Wolfgang Kerber of the Österreichische Zentralbibliothek für Physik, Vienna. Contents Editorial 2 Group meetings AGM Report 3 AGM Lecture programme: ‘Life with Bragg’ by John Nye 6 ‘George Francis Fitzgerald (1851-1901) - Scientific Saint?’ by Denis Weaire 9 ‘Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790) - a brief biography by Peter Ford 15 Reports Oxford visit 24 EPS History of physics group meeting, Graz, Austria 27 European Society for the History of Science - 2nd International conference 30 Sir Joseph Rotblat conference, Liverpool 35 Features: ‘Did Einstein visit Bratislava or not?’ by Juraj Sebesta 39 ‘Wadham College, Oxford and the Experimental Tradition’ by Allan Chapman 44 Book reviews JD Bernal – The Sage of Science 54 Harwell – The Enigma Revealed 59 Web report 62 News 64 Next Group meeting 65 Committee and contacts 68 2 Editorial Browsing through a copy of the group’s ‘aims and objectives’, I notice that part of its aims are ‘to secure the written, oral and instrumental record of British physics and to foster a greater awareness concerning the history of physics among physicists’ and I think that over the years much has been achieved by the group in tackling this not inconsiderable challenge. One must remember, however, that the situation at the time this was written was very different from now. -

Virtual Mentor American Medical Association Journal of Ethics

Virtual Mentor American Medical Association Journal of Ethics November 2011, Volume 13, Number 11: 747-845. Health Reform and the Practicing Physician From the Editors Leading through Change 750 Educating for Professionalism Clinical Cases Political Discussions in the Exam Room 753 Commentary by Jack P. Freer Physician Involvement with Politics—Obligation or Avocation? 757 Commentary by Thomas S. Huddle and Kristina L. Maletz New Guidelines for Cancer Screening in Older Patients 765 Commentary by Lisa M. Gangarosa Medical Education Graduate Medical Education Financing and the Role of the Volunteer Educator 769 Thomas J. Nasca The Code Says The AMA Code of Medical Ethics’ Opinion on Pay-for-Performance Programs and Patients’ Interests 775 Journal Discussion The Effects of Congressional Budget Reconciliation on Health Care Reform 777 Eugene B. Cone The Physician Group Practice Demonstration—A Valuable Model for ACOs? 783 Todd Ferguson www.virtualmentor.org Virtual Mentor, November 2011—Vol 13 747 Law, Policy, and Society Health Law Constitutional Challenges to the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act—A Snapshot 787 Lizz Esfeld and Allan Loup Policy Forum Maine’s Medical Liability Demonstration Project— Linking Practice Guidelines to Liability Protection 792 Gordon H. Smith Aligning Values with Value 796 Audiey C. Kao American Medical Association Policy—The Individual Mandate and Individual Responsibility 799 Valarie Blake Medicine and Society Health Reform and the Future of Medical Practice 803 Randy Wexler History, Art, and Narrative History of Medicine How Medicare and Hospitals Have Shaped American Health Care 808 Robert Martensen Medical Narrative Inside the Senate—A Physician Congressional Fellow’s Experience with Health Care Reform 813 Scott M. -

Bulletin September 2011

SEPTEMBER 2011 Volume 96, Number 9 INSPIRING QUALITY: Highest Standards, Better Outcomes FEATURES Stephen J. Regnier Editor ACS launches Inspiring Quality tour in Chicago 6 Lynn Kahn Tony Peregrin Director, Division of Integrated Communications Hospital puts ACS NSQIP® to the test and improves patient safety 9 Scott J. Ellner, DO, MPH, Hartford, CT Tony Peregrin Senior Editor Is there a role for race in science and medicine? 12 Diane S. Schneidman Dani O. Gonzalez; Linda I. Suleiman; Gabriel D. Ivey; Contributing Editor and Clive O. Callender, MD, FACS Tina Woelke ACS eases the pain of providing palliative care 19 Graphic Design Specialist Diane S. Schneidman Charles D. Mabry, Accountable care organizations: A primer for surgeons 27 MD, FACS Ingrid Ganske, MD, MPA; Megan M. Abbott, MD, MPH; Leigh A. Neumayer, and John Meara, MD, DMD, FACS MD, FACS Marshall Z. Schwartz, MD, Governors’ Committee on Surgical Infections and Environmental Risks: FACS An update 36 Mark C. Weissler, Linwood R. Haith, Jr., MD, FACS, FCCM MD, FACS Editorial Advisors Tina Woelke Front cover design DEPARTMENTS Future meetings Looking forward 4 Editorial by David B. Hoyt, MD, FACS, ACS Executive Director Clinical Congress 2011 San Francisco, CA, HPRI data tracks 38 October 23-27 Geographic distribution of general surgeons: Comparisons across time and specialties Simon Neuwahl; Thomas C. Ricketts, PhD, MPH; and Kristie Thompson 2012 Chicago, IL, September 30– Socioeconomic tips 42 October 4 Coding hernia and other complex abdominal repairs 2013 Washington, DC, Christopher Senkowski, MD, FACS; and Jenny Jackson, MPH October 6–10 State STATs 45 Graduated driver licensing: Keeping teen drivers safe Letters to the Editor should be Alexis Macias sent with the writer’s name, ad- dress, e-mail address, and daytime telephone number via e-mail to [email protected], or via mail to Stephen J. -

Thomas Willis and the Fevers Literature of the Seventeenth Century

Medical History, Supplement No. 1, 1981: 45-70 THOMAS WILLIS AND THE FEVERS LITERATURE OF THE SEVENTEENTH CENTURY by DON G. BATES* WE NEED not take literally the "common Adagy Nemo sine febri moritur," even for seventeenth-century England.' Nor is it likely that Fevers put "a period to the lives of most men".2 Nevertheless, the prevalence and importance of this "sad, comfortless, truculent disease" in those times cannot be doubted. Thomas Willis thought that Fevers had accounted for about a third of the deaths of mankind up to his day, and his contemporary and compatriot, if not his friend, Thomas Sydenham, guessed that two- thirds of deaths which were not due to violence were the result of that "army of pestiferous diseases", Fevers.3 These estimates are, of course, based almost entirely on impressions.4 But such impressions form the subject of this paper, for it is the contemporary Fevers literature upon which I wish to focus attention, the literature covering little more than a century following the death of the influential Jean Fernel in 1558. In what follows, I shall poke around in, rather than survey, the site in which this literature rests, trying to stake out, however disjointedly and incompletely, something of the intellectual, social, and natural setting in which it was produced. In keeping with the spirit of this volume, this is no more than an exploratory essay of a vast territory and, even so, to make it manageable, I have restricted myself largely to *Don G. Bates, M.D., Ph.D., Department of Humanities and Social Studies in Medicine. -

Virtual Mentor American Medical Association Journal of Ethics

Virtual Mentor American Medical Association Journal of Ethics November 2011, Volume 13, Number 11: 747-845. Health Reform and the Practicing Physician From the Editors Leading through Change 750 Educating for Professionalism Clinical Cases Political Discussions in the Exam Room 753 Commentary by Jack P. Freer Physician Involvement with Politics—Obligation or Avocation? 757 Commentary by Thomas S. Huddle and Kristina L. Maletz New Guidelines for Cancer Screening in Older Patients 765 Commentary by Lisa M. Gangarosa Medical Education Graduate Medical Education Financing and the Role of the Volunteer Educator 769 Thomas J. Nasca The Code Says The AMA Code of Medical Ethics’ Opinion on Pay-for-Performance Programs and Patients’ Interests 775 Journal Discussion The Effects of Congressional Budget Reconciliation on Health Care Reform 777 Eugene B. Cone The Physician Group Practice Demonstration—A Valuable Model for ACOs? 783 Todd Ferguson www.virtualmentor.org Virtual Mentor, November 2011—Vol 13 747 Law, Policy, and Society Health Law Constitutional Challenges to the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act—A Snapshot 787 Lizz Esfeld and Allan Loup Policy Forum Maine’s Medical Liability Demonstration Project— Linking Practice Guidelines to Liability Protection 792 Gordon H. Smith Aligning Values with Value 796 Audiey C. Kao American Medical Association Policy—The Individual Mandate and Individual Responsibility 799 Valarie Blake Medicine and Society Health Reform and the Future of Medical Practice 803 Randy Wexler History, Art, and Narrative History of Medicine How Medicare and Hospitals Have Shaped American Health Care 808 Robert Martensen Medical Narrative Inside the Senate—A Physician Congressional Fellow’s Experience with Health Care Reform 813 Scott M. -

Willis and the Virtuosi

Forum on Public Policy The Scientific Method through the Lens of Neuroscience; From Willis to Broad J. Lanier Burns, Professor, Research Professor of Theological Studies, Senior Professor of Systematic Theology, Dallas Theological Seminar Abstract: In an age of unprecedented scientific achievement, I argue that the neurosciences are poised to transform our perceptions about life on earth, and that collaboration is needed to exploit a vast body of knowledge for humanity’s benefit. The scientific method distinguishes science from the humanities and religion. It has evolved into a professional, specialized culture with a common language that has synthesized technological forces into an incomparable era in terms of power and potential to address persistent problems of life on earth. When Willis of Oxford initiated modern experimentation, ecclesial authorities held intellectuals accountable to traditional canons of belief. In our secularized age, science has ascended to dominance with its contributions to progress in virtually every field. I will develop this transition in three parts. First, modern experimentation on the brain emerged with Thomas Willis in the 17th Century. A conscientious Anglican, he postulated a “corporeal soul,” so that he could pursue cranial research. He belonged to a gifted circle of scientifically minded scholars, the Virtuosi, who assisted him with his Cerebri anatome. He coined a number of neurological terms, moved research from the traditional humoral theory to a structural emphasis, and has been remembered for the arterial structure at the base of the brain, the “Circle of Willis.” Second, the scientific method is briefly described as a foundation for understanding its development in neuroscience. -

NIH Clinical Center

August 2011 In this issue: Molecular Diagnostics CC Teen Retreat and Sibling Day Heart valve exhibit Clinical Center CC chosen as 2011 Maryland Works, Inc. Employer of the Year The Clinical Center was chosen as the 2011 Employer of the Year by Maryland Works, Inc., for its pilot NIH- Project SEARCH program. Maryland Works, Inc., is a statewide member- ship association that advocates for increasing employment and business ownership opportunities for people with disabilities or other barriers to employment. The NIH-Project SEARCH program graduated 12 young adults with disabilities from a 30-week unpaid internship at the CC in June. Project SEARCH works with hospitals and businesses in the United States, the United Kingdom, and Australia to provide opportunities for young adults Clinical Center Director Dr. John I. Gallin (center) connected with Dr. Seunghye Han (left), a clinical fellow in the Critical Care Medicine Department; and Dr. Henry Masur, Critical Care Medicine Department chief, with disabilities to learn employability at the reception for new clinical fellows hosted by the OCRTME on July 27. skills and gain work experience. “The success of this program is New NIH fellows receive warm reception both in the tangible work these indi- viduals have delivered and in the im- More than 70 clinical fellows were invited to welcome newcomers to the NIH team. pact they have had on the culture of to network with graduate medical educa- “Individuals are coming to the NIH the hospital,” said Denise Ford, chief tion training program directors, other NIH because they know that the value added of CC Hospitality Services, who led staff, institute and center scientifi c and to their training is in the area of research the pilot program. -

Library Exhibition

LIBRARY EXHIBITION DRAMATIS PERSONAE William Cole (1635-1716): Physician in Henry Sampson (1629-1700): Historian of the Worcester. Author of a treatise on the se- dissenters and physician to non- cretions of animals. conformists in London. Contributor to the Sir John Floyer (1649-1734): Physician in Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society. Lichfield. Author of works on asthma, John Wilkins (1614-1672): A cadaver. Once therapeutic bathing, and enthusiast for tak- Bishop of Chester. Founder member of the ing a patient’s pulse. Royal Society. Popularizer of Galileo. Crea- Richard Higgs (ca. 1632-1690): A physician in tor of a universal language. Coventry. Supplier to the pesthouse there. Thomas Willis (1621-1675): Physician in Ox- Richard Lower (1631-1691): Physician in ford. Associate of Messrs Boyle, Wren, London. Author of a major work on the Locke, Hooke. Writer of pioneering work heart and circulatory system, performed the on the brain. Sedleian Professor of Natural first successful blood-transfusion on two Philosophy at Oxford. dogs. Walter Needham (1631?-1691?): Anatomical lecturer to the Company of Surgeons. Au- thor of a work on foetal anatomy. The Medical Correspondence of Richard Higgs Gathered together in a single album kept here in the Library are a selection of letters from numerous key figures of the late 17th century flowering of scientific and medical thought and discovery that took place in Oxford. All of these letters are addressed to Dr Richard Higgs, and yet, for an associate of such illustrious figures, Higgs himself is elusive in the historical record. Originally from Gloucestershire, he appears to have matriculated at Queen’s College in Oxford in 1642 at around the age of 17, before embarking on medical training at Hart Hall, to graduate DM in 1659. -

Dr. Thomas Willis and His 'Circle' in the Brain

Historical Vignette Nepal Journal of Neuroscience 2:77-79, 2005 Dr. Thomas Willis and his ‘Circle’ in the Brain PVS Rana, MD, DM Department of Medicine With the advances in microneurosurgery and the ability to tackle (Neurology) diseases of the intracranial arteries at the base of the brain (often Manipal Teaching Hospital referred to as the Circle of Willis) surgically more effectively, accurate Manipal College of Medical Sciences knowledge of the intracranial vascular anatomy is increasingly Pokhara, Nepal important. Although Dr. Thomas Willis is best remembered for the Address for correspondence: accurate description of arterial anastomosis at the baseof the brain, PVS Rana, MD, DM his contribution to neuroanatomy, physiology and medical science in Department of Medicine general is vast, and several diseases bear his name. In this article an (Neurology) attempt has been made to review the life of Dr. Willis followed by a Manipal Teaching Hospital short description of the “Circle of Willis.” manipal College of Medical Sciences Pokhara, Nepal Key Words: anatomy, Circle of Willis, Dr. Thomas Willis Email: [email protected] Received, December 18, 2004 Accepted, December 30, 2004 “Anne Green was a 22- year-old woman who had been employed as a housemaid by Sir Thomas Read in Oxfordshire. She was probably seduced by his grandson, who turned her down when she became pregnant. The unlucky girl gave birth to a premature child whom she concealed. The dead boy was found, however, and Anne Green was accused of the murder of her own child. She was sentenced to die by hanging and the execution took place on December 14, 1650. -

Thomas Willis

NeuroQuantology 2005|Issue 4|Page 296-297 296 NQ-Biography, Thomas Willis NQ-Biography Thomas Willis Thomas Willis (1621-1673) was an English physician who played an important part in the history of the science of anatomy, was a co-founder of the Royal Society (1662) and is often considered the 'father of neurology'. Willis worked as a physician in Westminster, London, and from 1660 until his death was Sedleian Professor of Natural Philosophy at Oxford. He was a pioneer in research into the anatomy of the brain, nervous system and muscles. The "circle of Willis", a part of the brain's vascular system, was his discovery. His anatomy of the brain and nerves, as described in his Cerebri anatomi of 1664, is so minute and elaborate, and abounds so much in new information, that it presents an enormous contrast with the vague and meagre efforts of his predecessors. This work was not the result of his own personal and unaided exertions; he acknowledged his debt to Sir Christopher Wren and Thomas Millington, and his fellow-anatomist Richard Lower. Wren was the illustrator of the magnificent figures in the book. Willis was the first natural philosopher to use the term "reflex action" to describe elemental acts of the nervous system. He also wrote Pathologiae Cerebri et Nervosi Generis Specimen, 1667 (An Essay of the Pathology of the Brain and Nervous Stock) and of De Anima Brutorum, 1672 (Discourses Concerning the Souls of Brutes). Willis was the first to number the cranial nerves in the order in which they are now usually enumerated by anatomists. -

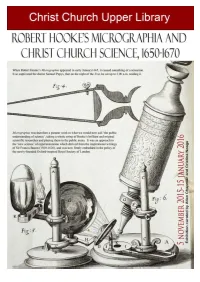

Robert Hooke's Micrographia

Robert Hooke's Micrographia and Christ Church Science, 1650-1670 is curated by Allan Chapman and Cristina Neagu, and will be open from 5 November 2015 to 15 January 2016. An exhibition to mark the 350th anniversary of the publication of Robert Hooke's Micrographia, the first book of microscopy. The event is organized at Christ Church, where Hooke was an undergraduate from 1653 to 1658, and includes a lecture (on Monday 30 November at 5:15 pm in the Upper Library) by the science historian Professor Allan Chapman. Visiting hours: Monday: 2.00 pm - 4.30 pm; Tuesday - Thursday: 10.00 am - 1.00 pm; 2.00 pm - 4.00 pm; Friday: 10.00 am - 1.00 pm Article on Robert Hooke and Early science at Christ Church by Allan Chapman Scientific equipment on loan from Allan Chapman Photography Alina Nachescu Exhibition catalogue and poster by Cristina Neagu Robert Hooke's Micrographia and Early Science at Christ Church, 1660-1670 Micrographia, Scheme 11, detail of cells in cork. Contents Robert Hooke's Micrographia and Christ Church Science, 1650-1670 Exhibition Catalogue Exhibits and Captions Title-page of the first edition of Micrographia, published in 1665. Robert Hooke’s Micrographia and Christ Church Science, 1650-1670 When Robert Hooke’s Micrographia: or Some Physiological Descriptions of Minute Bodies Made by Magnifying Glasses with Observations and Inquiries thereupon appeared in early January 1665, it caused something of a sensation. It so captivated the diarist Samuel Pepys, that on the night of the 21st, he sat up to 2.00 a.m. -

Annual Report to the Community Thank You All So Very Much for the Support and Care Given to Our Mother and Family Over the Last Several Months

2010 Annual Report to the Community Thank you all so very much for the support and care given to our mother and family over the last several months. We were so blessed to have such a loving and professional team by our side through this most difficult time. Your genuine concern and care will never be forgotten. – A grateful family Now I have graduated Full Circle I want to thank you for your continued support with the monthly bereavement mailings. I find them most helpful. I appreciate the care and concern you have given my family especially when we needed it. I support all the good works you do. – A grateful bereavement client Hospice Savannah, Inc., a not-for-profit organization, provides our community the best services and resources on living with a life-limiting illness, dying, death, grief and loss. – Hospice Savannah Mission Statement 2 2010 - 2011 BOARD OF DIRECTORS FOUNDATION TRUSTEES Fran Kaminsky, Chair Elizabeth Oxnard, Chair Holden Hayes, Vice Chair Samuel Adams, Vice Chair Floyd Adams, Jr., Secretary Myron Kaminsky, Secretary/Treasurer Bruce Barragan, Treasurer Kacey Ratterree, Member-at-large William A. Baker, Jr. Christopher E. Klein, Past Chair Randall K. Bart E. B. (Zeke) Gaines, III William A. Baker, Jr. Martin Greenberg, M.D. Jean Beltramini Holden Hayes Kathleen DeLoach Benton Myron Kaminsky Sister Maureen Connolly Christopher E. Klein Roenia DeLoach, Ph.D. Carolyn Luck Virginia A. Edwards Heys McMath, III E. B. (Zeke) Gaines, III Caroline Nusloch Theodora (T.) Gongaware, M.D. Myra J. Phillips Martin Greenberg, M.D. James Toby Roberts, Sr. R. Vincent Martin, III Joseph R.