Malcolm Rogers' Arizona Fieldwork, 1926–1956

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Lower Gila Region, Arizona

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR HUBERT WORK, Secretary UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY GEORGE OTIS SMITH, Director Water-Supply Paper 498 THE LOWER GILA REGION, ARIZONA A GEOGBAPHIC, GEOLOGIC, AND HTDBOLOGIC BECONNAISSANCE WITH A GUIDE TO DESEET WATEEING PIACES BY CLYDE P. ROSS WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1923 ADDITIONAL COPIES OF THIS PUBLICATION MAT BE PROCURED FROM THE SUPERINTENDENT OF DOCUMENTS GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON, D. C. AT 50 CENTS PEE COPY PURCHASER AGREES NOT TO RESELL OR DISTRIBUTE THIS COPT FOR PROFIT. PUB. RES. 57, APPROVED MAT 11, 1822 CONTENTS. I Page. Preface, by O. E. Melnzer_____________ __ xr Introduction_ _ ___ __ _ 1 Location and extent of the region_____._________ _ J. Scope of the report- 1 Plan _________________________________ 1 General chapters _ __ ___ _ '. , 1 ' Route'descriptions and logs ___ __ _ 2 Chapter on watering places _ , 3 Maps_____________,_______,_______._____ 3 Acknowledgments ______________'- __________,______ 4 General features of the region___ _ ______ _ ., _ _ 4 Climate__,_______________________________ 4 History _____'_____________________________,_ 7 Industrial development___ ____ _ _ _ __ _ 12 Mining __________________________________ 12 Agriculture__-_______'.____________________ 13 Stock raising __ 15 Flora _____________________________________ 15 Fauna _________________________ ,_________ 16 Topography . _ ___ _, 17 Geology_____________ _ _ '. ___ 19 Bock formations. _ _ '. __ '_ ----,----- 20 Basal complex___________, _____ 1 L __. 20 Tertiary lavas ___________________ _____ 21 Tertiary sedimentary formations___T_____1___,r 23 Quaternary sedimentary formations _'__ _ r- 24 > Quaternary basalt ______________._________ 27 Structure _______________________ ______ 27 Geologic history _____ _____________ _ _____ 28 Early pre-Cambrian time______________________ . -

Department of the Interior U.S

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR U.S. FISH AND WILDLIFE SERVICE REGION 2 DIVISION OF ENVIRONMENTAL CONTAMINANTS CONTAMINANTS IN BIGHORN SHEEP ON THE KOFA NATIONAL WIL DLIFE REFUGE, 2000-2001 By Carrie H. Marr, Anthony L. Velasco1, and Ron Kearns2 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Arizona Ecological Services Office 2321 W. Royal Palm Road, Suite 103 Phoenix, Arizona 85021 August 2004 2 ABSTRACT Soils of abandoned mines on the Kofa National Wildlife Refuge (KNWR) are contaminated with arsenic, barium, mercury, manganese, lead, and zinc. Previous studies have shown that trace element and metal concentrations in bats were elevated above threshold concentrations. High trace element and metal concentrations in bats suggested that bighorn sheep also may be exposed to these contaminants when using abandoned mines as resting areas. We found evidence of bighorn sheep use, bighorn sheep carcasses, and scat in several abandoned mines. To determine whether bighorn sheep are exposed to, and are accumulating hazardous levels of metals while using abandoned mines, we collected soil samples, as well as scat and bone samples when available. We compared mine soil concentrations to Arizona non-residential clean up levels. Hazard quotients were elevated in several mines and elevated for manganese in one Sheep Tank Mine sample. We analyzed bighorn sheep tissues for trace elements. We obtained blood, liver, and bone samples from hunter-harvested bighorn in 2000 and 2001. Arizona Game and Fish Department also collected blood from bighorn during a translocation operation in 2001. Iron and magnesium were elevated in tissues compared to reference literature concentrations in other species. Most often, domestic sheep baseline levels were used for comparison because of limited available data for bighorn sheep. -

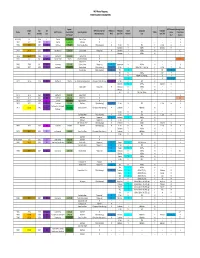

MS4 Route Mapping PRIORITIZATION PARAMETERS

MS4 Route Mapping PRIORITIZATION PARAMETERS Approx. ADOT Named or Average Annual Length Year Age OAW/Impaired/ Not‐ Within 1/4 Pollutants ADOT Designated Pollutants Route ADOT Districts Annual Traffic Receiving Waters TMDL? Given Precipitation (mi) Installed (yrs) Attaining Waters? Mile? (per EPA) Pollutant? Uses (per EPA) (Vehicles/yr) WLA? (inches) SR 24 (802) 1.0 2014 5 Central 11,513,195 Queen Creek N ‐‐ ‐‐ ‐‐ ‐‐ ‐‐ ‐‐ ‐‐ 6 SR 51 16.7 1987 32 Central 61,081,655 Salt River N ‐‐ ‐‐ ‐‐ ‐‐ ‐‐ ‐‐ ‐‐ 6 SR 61 76.51 1935 84 Northeast 775,260 Little Colorado River Y (Not attaining) N E. Coli N FBC Y E. Coli N 7 Sediment Y A&Wc Y Sediment N SR 64 108.31 1932 87 Northcentral 2,938,250 Colorado River Y (Impaired) N Sediment Y A&Wc N ‐‐ ‐‐ 8.5 Selenium Y A&Wc N ‐‐ ‐‐ SR 66 66.59 1984 35 Northwest 5,154,530 Truxton Wash N ‐‐ ‐‐ ‐‐ ‐‐ ‐‐ ‐‐ ‐‐ 7 SR 67 43.4 1941 78 Northcentral 39,055 House Rock Wash N ‐‐ ‐‐ ‐‐ ‐‐ ‐‐ ‐‐ ‐‐ 17 Kanab Creek N ‐‐ ‐‐ ‐‐ ‐‐ ‐‐ ‐‐ ‐‐ SR 68 27.88 1941 78 Northwest 5,557,490 Colorado River Y (Impaired) Y Temperature N A&Ww N ‐‐ ‐‐ 6 SR 69 33.87 1938 81 Northwest 17,037,470 Granite Creek Y (Not attaining) Y E. Coli N A&Wc, FBC, FC, AgI, AgL Y E. Coli Y 9.5 Watson Lake Y (Not attaining) Y TN Y ‐‐ Y TN Y DO N A&Ww Y DO Y pH N A&Ww, FBC, AgI, AgL Y pH Y TP Y ‐‐ Y TP Y SR 71 24.16 1936 83 Northwest 296,015 Sols Wash/Hassayampa River Y (Impaired, Not attaining) Y E. -

Geology of Cienega Mining District, Northwestern Yuma County, Arizona

Scholars' Mine Masters Theses Student Theses and Dissertations 1965 Geology of Cienega Mining District, Northwestern Yuma County, Arizona Elias Zambrano Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsmine.mst.edu/masters_theses Part of the Geology Commons Department: Recommended Citation Zambrano, Elias, "Geology of Cienega Mining District, Northwestern Yuma County, Arizona" (1965). Masters Theses. 7104. https://scholarsmine.mst.edu/masters_theses/7104 This thesis is brought to you by Scholars' Mine, a service of the Missouri S&T Library and Learning Resources. This work is protected by U. S. Copyright Law. Unauthorized use including reproduction for redistribution requires the permission of the copyright holder. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GEOLOGY OF CIENEGA MINING DISTRICT, NORTHWESTERN YUM.1\, COUNTY, ARIZONA BY ELIAS ZAMBRANO I J'i~& A THESIS submitted to the faculty of the UNIVERSITY OF MISSOURI AT ROLLA in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE IN GEOLOGY Rolla, Missouri 1965 ~!'Approved by ~2/~advisor) ~ ~·-~~ ii ABSTRACT In the mapped area three metamorphic units crop out: calc-silicates and marble, gneiss, and a conglomerate- schist section. The first one consists of a series of intercalations of calc-silicate rocks, local marbles, and greenschist. Quartzite appears in the upper part of the section. This section passes transitionally to the gneiss, which is believed to be of sedimentary origin. Features indicative of sedimentary origin include inter calation with marble, relic bedding which can be observed locally, intercalation of greenschist clearly of sedimentary origin, lack of homogeneity in composition with both lateral and vertical variation occurring, roundness of zircon grains, and lack of zoning in the feldspars. -

The Maricopa County Wildlife Connectivity Assessment: Report on Stakeholder Input January 2012

The Maricopa County Wildlife Connectivity Assessment: Report on Stakeholder Input January 2012 (Photographs: Arizona Game and Fish Department) Arizona Game and Fish Department In partnership with the Arizona Wildlife Linkages Workgroup TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES ............................................................................................................................ i RECOMMENDED CITATION ........................................................................................................ ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ................................................................................................................. ii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................................ iii DEFINITIONS ................................................................................................................................ iv BACKGROUND ................................................................................................................................ 1 THE MARICOPA COUNTY WILDLIFE CONNECTIVITY ASSESSMENT ................................... 8 HOW TO USE THIS REPORT AND ASSOCIATED GIS DATA ................................................... 10 METHODS ..................................................................................................................................... 12 MASTER LIST OF WILDLIFE LINKAGES AND HABITAT BLOCKSAND BARRIERS ................ 16 REFERENCE MAPS ....................................................................................................................... -

Reintroduction of the Tarahumara Frog (Rana Tarahumarae) in Arizona: Lessons Learned

Herpetological Conservation and Biology 15(2):372–389. Submitted: 12 December 2019; Accepted: 11 June 2020; Published: 31 August 2020. REINTRODUCTION OF THE TARAHUMARA FROG (RANA TARAHUMARAE) IN ARIZONA: LESSONS LEARNED JAMES C. RORABAUGH1,8, AUDREY K. OWENS2, ABIGAIL KING3, STEPHEN F. HALE4, STEPHANE POULIN5, MICHAEL J. SREDL6, AND JULIO A. LEMOS-ESPINAL7 1Post Office Box 31, Saint David, Arizona 85630, USA 2Arizona Game and Fish Department, 5000 West Carefree Highway, Phoenix, Arizona 85086, USA 3Jack Creek Preserve Foundation, Post Office Box 3, Ennis, Montana 59716, USA 4EcoPlan Associates, Inc., 3610 North Prince Village Place, Suite 140, Tucson, Arizona 85719, USA 5Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum, 2021 North Kinney Road, Tucson, Arizona 85743, USA 6Arizona Game and Fish Department (retired), 5000 West Carefree Highway, Phoenix, Arizona 85086, USA 7Laboratorio de Ecología, Unidad de Biotecnología y Prototipos, Facultad de Estudios Superiores Iztacala, Avenida De Los Barrios No. 1, Colonia Los Reyes Iztacala, Tlalnepantla, Estado de México 54090, México 8Corresponding author, e-mail: [email protected] Abstract.—The Tarahumara Frog (Rana tarahumarae) disappeared from the northern edge of its range in south- central Arizona, USA, after observed declines and die-offs from 1974 to 1983. Similar declines were noted in Sonora, Mexico; however, the species still persists at many sites in Mexico. Chytridiomycosis was detected during some declines and implicated in others; however, airborne pollutants from copper smelters, predation, competition, and extreme weather may have also been contributing factors. We collected Tarahumara Frogs in Sonora for captive rearing and propagation beginning in 1999, and released frogs to two historical localities in Arizona, including Big Casa Blanca Canyon and vicinity, Santa Rita Mountains, and Sycamore Canyon, Atascosa Mountains. -

Strategic Long-Range Transportation Plan for the Colorado River Indian

2014 Strategic Long Range Transportation Plan for the Colorado River Indian Tribes Final Report Prepared by: Prepared for: COLORADO RIVER INDIAN TRIBES APRIL 2014 Project Management Team Arizona Department of Transportation Colorado River Indian Tribes 206 S. 17th Ave. 26600 Mohave Road Mail Drop: 310B Parker, Arizona 85344 Phoenix, AZ 85007 Don Sneed, ADOT Project Manager Greg Fisher, Tribal Project Manager Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Telephone: 602-712-6736 Telephone: (928) 669-1358 Mobile: (928) 515-9241 Tony Staffaroni, ADOT Community Relations Project Manager Email: [email protected] Phone: (602) 245-4051 Project Consultant Team Kimley-Horn and Associates, Inc. 333 East Wetmore Road, Suite 280 Tucson, AZ 85705 Mary Rodin, AICP Email: [email protected] Telephone: 520-352-8626 Mobile: 520-256-9832 Field Data Services of Arizona, Inc. 21636 N. Dietz Drive Maricopa, Arizona 85138 Sharon Morris, President Email: [email protected] Telephone: 520-316-6745 This report has been funded in part through financial assistance from the Federal Highway Administration, U.S. Department of Transportation. The contents of this report reflect the views of the authors, who are responsible for the facts and the accuracy of the data, and for the use or adaptation of previously published material, presented herein. The contents do not necessarily reflect the official views or policies of the Arizona Department of Transportation or the Federal Highway Administration, U.S. Department of Transportation. This report does not constitute a standard, specification, or regulation. Trade or manufacturers’ names that may appear herein are cited only because they are considered essential to the objectives of the report. -

Summits on the Air – ARM for the USA (W7A

Summits on the Air – ARM for the U.S.A (W7A - Arizona) Summits on the Air U.S.A. (W7A - Arizona) Association Reference Manual Document Reference S53.1 Issue number 5.0 Date of issue 31-October 2020 Participation start date 01-Aug 2010 Authorized Date: 31-October 2020 Association Manager Pete Scola, WA7JTM Summits-on-the-Air an original concept by G3WGV and developed with G3CWI Notice “Summits on the Air” SOTA and the SOTA logo are trademarks of the Programme. This document is copyright of the Programme. All other trademarks and copyrights referenced herein are acknowledged. Document S53.1 Page 1 of 15 Summits on the Air – ARM for the U.S.A (W7A - Arizona) TABLE OF CONTENTS CHANGE CONTROL....................................................................................................................................... 3 DISCLAIMER................................................................................................................................................. 4 1 ASSOCIATION REFERENCE DATA ........................................................................................................... 5 1.1 Program Derivation ...................................................................................................................................................................................... 6 1.2 General Information ..................................................................................................................................................................................... 6 1.3 Final Ascent -

Central Arizona Salinity Study --- Phase I

CENTRAL ARIZONA SALINITY STUDY --- PHASE I Technical Appendix D HYDROLOGIC REPORT ON THE GILA BEND BASIN Prepared for: United States Department of Interior Bureau of Reclamation Prepared by: Brown and Caldwell 201 East Washington Street, Suite 500 Phoenix, Arizona 85004 D-1 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE TABLE OF CONTENTS ................................................................................................................ 2 LIST OF TABLES .......................................................................................................................... 3 LIST OF FIGURES ........................................................................................................................ 3 1.0 INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................. 4 2.0 PHYSICAL SETTING ....................................................................................................... 5 3.0 GENERALIZED GEOLOGY ............................................................................................ 6 3.1 BEDROCK GEOLOGY ......................................................................................... 6 3.2 BASIN GEOLOGY ................................................................................................ 6 4.0 HYDROGEOLOGIC CONDITIONS ................................................................................ 8 4.1 GROUNDWATER OCCURRENCE AND MOVEMENT ................................... 8 4.2 GROUNDWATER QUALITY ............................................................................. -

Federal Register/Vol. 76, No. 87/Thursday, May 5, 2011/Rules

Federal Register / Vol. 76, No. 87 / Thursday, May 5, 2011 / Rules and Regulations 25593 DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Service’s Arizona Ecological Services or result in the destruction or adverse Office at 2321 W. Royal Palm Road, modification of designated critical Fish and Wildlife Service Suite 103, Phoenix, AZ 85021. habitat. Section 7 of the Act does not FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: affect activities undertaken on private or 50 CFR Part 17 Steve Spangle, Field Supervisor, other non-Federal land unless they are [Docket No. FWS–R2–ES–2009–0077; Arizona Ecological Services Office, 2321 authorized, funded, or carried out by a 92220–1113–0000; ABC Code: C3] W. Royal Palm Road, Suite 103, Federal agency. Phoenix, AZ 85021 (telephone 602– Under section 10(j) of the Act, the RIN 1018–AW63 242–0210, facsimile 602–242–2513). If Secretary of the Department of the Interior can reestablish populations Endangered and Threatened Wildlife you use a telecommunications device for the deaf (TDD), call the Federal outside the species’ current range and and Plants; Establishment of a designate them as ‘‘experimental.’’ With Nonessential Experimental Population Information Relay Service (FIRS) at 800–877–8339. the experimental population of Sonoran Pronghorn in designation, the relevant population is Southwestern Arizona SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION: treated as threatened for purposes of AGENCY: Fish and Wildlife Service, Background section 9 of the Act, regardless of the species’ designation elsewhere in its Interior. It is our intent to discuss only those ACTION: Final rule. range. Threatened designation allows us topics directly relevant to this final rule discretion in devising management establishing a Sonoran pronghorn SUMMARY: We, the U.S. -

Fvie Year Bid Date Report

May 10, 2012 ARIZONA DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION PROGRAM & PROJECT MANAGEMENT SECTION 5-YEAR BID DATE REPORT This report contains the construction projects from the new 5-Year Program. The report is sorted 7 different ways; 1) by project name, 3) by bid date, route and beginning milepost, 4) by TRACS number, 5) by route, beginning milepost and TRACS 6) by engineering district, route, beginning milepost and TRACS number and 7) by CPSID. PROJECT CATEGORIES Several projects are on “special” status as indicated by a bid date in the year 2050. The special categories are listed below. STATUS PROJECT CATEGORY 02/25/2050 IGA/JPA PROJECTS WITHOUT SCHEDULE 05/25/2050 PROJECTS IN THE NEW 5-YEAR PROGRAM IN THE PROCESS OF BEING SCHEDULED. 06/25/2050 DESIGN PROJECTS IN THE 5-YEAR PROGRAM WITHOUT CORRESPONDING CONSTRUCTION PROJECT 08/25/2050 PROJECTS THAT ARE ON “HOLD” STATUS UNTIL THE PROBLEMS ARE RESOLVED AND A DECISION IS MADE ON RESCHEDULING. PROJECT DEVELOPMENT SHOULD CONTINUE IF POSSIBLE. 09/25/2050 PROJECTS THAT HAVE BEEN DELETED FROM THE CURRENT 5-YEAR CONSTRUCTION PROGRAM. WE WILL MAINTAIN THESE PROJECTS ON THE PRIMAVERA SYSTEM FOR RECORD. PROJECT DEVELOPMENT IS TERMINATED FOR THESE PROJECTS . DESIGN FIRM ABBREVIATIONS AMEC AMEC LSD Logan Simpson Design AZTC Aztec Engineering MB Michael Baker Jr., Inc. BN Burgess & Niple MBD1 Michael Baker/Design One BRW BRW MMLA MMLA, Inc. BSA Bulduc, Smiley & Associates. Inc. OLSN Olsson & Associates C&B Carter & Burgess PARS Parsons Transportation Group CANN Cannon & Associates PBQD PBQD - Parsons Brinkerhoff Quade & Douglas CDG Corral Dybas Group, Inc. PBSJ PBS&J CH2M CH2M Hill PREM Premier Engineering Corporation DIBL Dibble & Associates RBF RBF Consulting DMJM DMJM+Harris RPOW Ritoch Powell & Associates EEC EEC SCON Stanley Consultants ENTR Entranco STEC Stantec Consulting, Inc. -

Final Environmental Assessment for Reestablishment of Sonoran Pronghorn

Final Environmental Assessment for Reestablishment of Sonoran Pronghorn U.S. Department of the Interior Fish and Wildlife Service Region 2 6 October 2010 This page left blank intentionally 6 October 2010 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 PURPOSE OF AND NEED FOR ACTION............................................ 1 1.1 Proposed Action.............................................................. 2 1.2 Project Need................................................................. 6 1.3 Background Information on Sonoran Pronghorn . 9 1.3.1 Taxonomy.............................................................. 9 1.3.2 Historic Distribution and Abundance......................................... 9 1.3.3 Current Distribution and Abundance........................................ 10 1.3.4 Life History............................................................ 12 1.3.5 Habitat................................................................ 13 1.3.6 Food and Water......................................................... 18 1.3.7 Home Range, Movement, and Habitat Area Requirements . 18 1.4 Project Purpose ............................................................. 19 1.5 Decision to be Made.......................................................... 19 1.6 Compliance with Laws, Regulations, and Plans . 19 1.7 Permitting Requirements and Authorizations Needed . 21 1.8 Scoping Summary............................................................ 21 1.8.1 Internal Agency Scoping.................................................. 21 1.8.2 Public Scoping ........................................................