The Missing Profits of Nations: Online Appendix

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Where to Spend the Next Million? Approaches to Addressing Constraints Faced by Developing Countries As They Seek to Benefit from the Gains from Trade

a “A welcome trend is emerging towards more clinical and thoughtful to Spend the Next Million? Where approaches to addressing constraints faced by developing countries as they seek to benefit from the gains from trade. But this evolving approach brings Where to Spend the Next with it formidable analytical challenges that we have yet to surmount. We need to know more about available options for evaluating Aid for Trade, Million? which interventions yield the highest returns, and whether experiences in one development area can be transplanted to another. These are some of the issues addressed in this excellent volume.” Applying Impact Evaluation to Pascal Lamy, Director-General, World Trade Organization Trade Assistance “Five years into the Aid for Trade project, we still need to learn much more about what works and what does not. Our initiatives offer excellent opportunities to evaluate impacts rigorously. That is the way to better connect aid to results. The collection of essays in this well-timed volume shows that the new approaches to evaluation that we are applying to Assistance Applyng Impact Evaluation to Trade education, poverty, or health programs can also be used to assess the results of policies to promote or assist trade. This book offers a valuable contribution to the drive to ensure value for aid money.” Robert Zoellick, President, The World Bank a THE WORLD BANK ISBN 978-1-907142-39-0 edited by Olivier Cadot, Ana M. Fernandes, Julien Gourdon and Aaditya Mattoo a THE WORLD BANK 9 781907 142390 WHERE TO SPEND THE NEXT MILLION? Where to Spend the Next Million? Applying Impact Evaluation to Trade Assistance Copyright © 2011 by The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank 1818 H Street, NW, Washington, DC 20433, USA ISBN: 978-1-907142-39-0 All rights reserved The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Executive Directors of the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank or the governments they represent. -

The Many Faces of Exclusion: 2018 End of Childhood Report

THE MANY FACES OF EXCLUSION END OF CHILDHOOD REPORT 2018 Six-year-old Arwa* and her family were displaced from their home by armed conflict in Iraq. CONTENTS 1 Introduction 3 End of Childhood Index Results 2017 vs. 2018 7 THREAT #1: Poverty 15 THREAT #2: Armed Conflict 21 THREAT #3: Discrimination Against Girls 27 Recommendations 31 End of Childhood Index Rankings 32 Complete End of Childhood Index 2018 36 Methodology and Research Notes 41 Endnotes 45 Acknowledgements * after a name indicates the name has been changed to protect identity. Published by Save the Children 501 Kings Highway East, Suite 400 Fairfield, Connecticut 06825 United States (800) 728-3843 www.SavetheChildren.org © Save the Children Federation, Inc. ISBN: 1-888393-34-3 Photo:## SAVE CJ ClarkeTHE CHILDREN / Save the Children INTRODUCTION The Many Faces of Exclusion Poverty, conflict and discrimination against girls are putting more than 1.2 billion children – over half of children worldwide – at risk for an early end to their childhood. Many of these at-risk children live in countries facing two or three of these grave threats at the same time. In fact, 153 million children are at extreme risk of missing out on childhood because they live in countries characterized by all three threats.1 In commemoration of International Children’s Day, Save the Children releases its second annual End of Childhood Index, taking a hard look at the events that rob children of their childhoods and prevent them from reaching their full potential. WHO ARE THE 1.2 BILLION Compared to last year, the index finds the overall situation CHILDREN AT RISK? for children appears more favorable in 95 of 175 countries. -

IAEA Nuclear Energy Series Managing the Unexpected in Decommissioning No

IAEA Nuclear Energy Series IAEA Nuclear No. NW-T-2.8 No. IAEA Nuclear Energy Series Managing the Unexpected in Decommissioning Managing the Unexpected No. NW-T-2.8 Basic Managing the Principles Unexpected in Decommissioning Objectives Guides Technical Reports INTERNATIONAL ATOMIC ENERGY AGENCY VIENNA ISBN 978–92–0–103615–5 ISSN 1995–7807 @ 15-40561_PUB1702_cover.indd 1,3 2016-03-30 10:56:45 IAEA Nuclear Energy Series IAEA Nuclear IAEA NUCLEAR ENERGY SERIES PUBLICATIONS STRUCTURE OF THE IAEA NUCLEAR ENERGY SERIES No. NW-T-2.8 No. Under the terms of Articles III.A and VIII.C of its Statute, the IAEA is authorized to foster the exchange of scientific and technical information on the peaceful uses of atomic energy. The publications in the IAEA Nuclear Energy Series provide information in the areas of nuclear power, nuclear fuel cycle, in Decommissioning Managing the Unexpected radioactive waste management and decommissioning, and on general issues that are relevant to all of the above mentioned areas. The structure of the IAEA Nuclear Energy Series comprises three levels: 1 — Basic Principles and Objectives; 2 — Guides; and 3 — Technical Reports. The Nuclear Energy Basic Principles publication describes the rationale and vision for the peaceful uses of nuclear energy. Nuclear Energy Series Objectives publications explain the expectations to be met in various areas at different stages of implementation. Nuclear Energy Series Guides provide high level guidance on how to achieve the objectives related to the various topics and areas involving the peaceful uses of nuclear energy. Nuclear Energy Series Technical Reports provide additional, more detailed information on activities related to the various areas dealt with in the IAEA Nuclear Energy Series. -

Child Mortalitymortality Estimationestimation

LevelsLevels && TrendsTrends inin ReportReport 20142019 ChildChild EstimatesEstimates Developeddeveloped byby thethe UNUN Inter-agencyInter-agency Group Group for for MortalityMortality ChildChild MortalityMortality EstimationEstimation United Nations This report was prepared at UNICEF headquarters by Lucia Hug, David Sharrow and Danzhen You, with support from Mark Hereward and Yanhong Zhang, on behalf of the United Nations Inter-agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation (UN IGME). Organizations and individuals involved in generating country-specific estimates of child mortality United Nations Children’s Fund Lucia Hug, Sinae Lee, David Sharrow, Danzhen You World Health Organization Bochen Cao, Jessica Ho, Wahyu Retno Mahanani, Kathleen Louise Strong World Bank Group Emi Suzuki United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division Kirill Andreev, Lina Bassarsky, Victor Gaigbe-Togbe, Patrick Gerland, Danan Gu, Sara Hertog, Nan Li, Thomas Spoorenberg, Philipp Ueffing, Mark Wheldon United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean, Population Division Guiomar Bay, Helena Cruz Castanheira Special thanks to the Technical Advisory Group of the UN IGME for providing technical guidance on methods for child mortality estimation Leontine Alkema, University of Massachusetts, Amherst Kenneth Hill (Chair), Stanton-Hill Research Robert Black, Johns Hopkins University Bruno Masquelier, University of Louvain Simon Cousens, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine Colin Mathers, University of Edinburgh Trevor Croft, The Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) Program, ICF Jon Pedersen, Fafo Michel Guillot, University of Pennsylvania and French Institute for Jon Wakefield, University of Washington Demographic Studies (INED) Neff Walker, Johns Hopkins University Special thanks to the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation for supporting UNICEF’s child mortality estimation work. -

New Horizons for Health Through Mobile Technologies

mHealth New horizons for health through mobile technologies Based on the findings of the second global survey on eHealth Global Observatory for eHealth series - Volume 3 WHO Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data mHealth: New horizons for health through mobile technologies: second global survey on eHealth. 1.Cellular phone - utilization. 2.Computers, Handheld - utilization. 3.Telemedicine. 4.Medical informatics. 5.Technology transfer. 6.Data collection. I.WHO Global Observatory for eHealth. ISBN 978 92 4 156425 0 (NLM classification: W 26.5) © World Health Organization 2011 All rights reserved. Publications of the World Health Organization are available on the WHO web site (www.who.int) or can be purchased from WHO Press, World Health Organization, 20 Avenue Appia, 1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland (tel.: +41 22 791 3264; fax: +41 22 791 4857; e-mail: [email protected]). Requests for permission to reproduce or translate WHO publications – whether for sale or for noncommercial distribution – should be addressed to WHO Press through the WHO web site (http://www.who.int/about/ licensing/copyright_form/en/index.html). The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted lines on maps represent approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement. The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers’ products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by the World Health Organization in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. -

In the United States District Court for the District of Massachusetts

Case 1:20-cv-10015-DJC Document 29 Filed 07/08/20 Page 1 of 78 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF MASSACHUSETTS EQUAL MEANS EQUAL, THE YELLOW ROSES, KATHERINE WEITBRECHT, Plaintiffs, v. Civil Action No. 20-cv-10015-DJC DAVID S. FERRIERO, in his official Capacity as Archivist of the United States, Defendant. ______________________________________________________________________ AMICUS CURIAE BRIEF IN SUPPORT OF PLAINTIFFS The United States Conference of Mayors Equal Means ERA 38 Agree for Georgia LARatifyERA Jodi Siegel* Kristine L. Roberts Chelsea Dunn* Mass. BBO No. 651491 *Pro Hac Vice forthcoming SOUTHERN LEGAL COUNSEL, INC. BAKER, DONELSON, 1229 NW 12th Avenue BEARMAN, CALDWELL & Gainesville, FL 32601 BERKOWITZ, P.C. (305) 271-8890 165 Madison Avenue [email protected] First Tennessee Building [email protected] Suite 2000 Washington, D.C. 20001 (901) 526-2000 [email protected] Counsel for Amici Curiae Case 1:20-cv-10015-DJC Document 29 Filed 07/08/20 Page 2 of 78 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTERESTS OF THE AMICI ........................................................................................... 1 ARGUMENT .................................................................................................................... 3 I. INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................... 3 II. WITH THE RATIFICATION OF THE ERA, THE U.S. JOINS OTHER NATIONS IN GUARANTEEING EQUALITY FOR WOMEN ..................... 3 III. SEX DISCRIMINATION MAY BE -

Alcohol and Injuries Emergency Department Studies in an International Perspective

Alcohol And InjurIes Emergency Department Studies in an International Perspective Alcohol And InjurIes Emergency Department Studies in an International Perspective Editors: Cheryl J. Cherpitel, Guilherme Borges, Norman Giesbrecht, Daniel Hungerford, Margie Peden, Vladimir Poznyak, Robin Room, Tim Stockwell WHO Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data: Alcohol and injuries: emergency department studies in an international perspective. 1.Alcohol drinking - adverse effects. 2.Alcoholic intoxication - diagnosis. 3.Wounds and injuries - etiology. 4.Emergency service, Hospital. 5.Multicenter studies. I.World Health Organization. ISBN 978 92 4 154784 0 (NLM classification: WM 274) © World Health Organization 2009 All rights reserved. Publications of the World Health Organization can be obtained from WHO Press, World Health Organization, 20 Avenue Appia, 1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland (tel.: +41 22 791 3264; fax: +41 22 791 4857; e-mail: [email protected]). Requests for permission to reproduce or trans- late WHO publications – whether for sale or for noncommercial distribution – should be addressed to WHO Press, at the above address (fax: +41 22 791 4806; e-mail: [email protected]). The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization concern- ing the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted lines on maps represent approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement. The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers’ products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by the World Health Organization in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. -

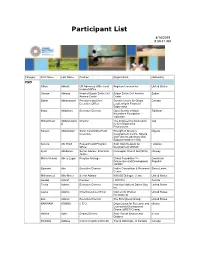

Participant List

Participant List 4/14/2019 8:59:41 AM Category First Name Last Name Position Organization Nationality CSO Jillian Abballe UN Advocacy Officer and Anglican Communion United States Head of Office Osman Abbass Head of Sudan Sickle Cell Sudan Sickle Cell Anemia Sudan Anemia Center Center Babak Abbaszadeh President and Chief Toronto Centre for Global Canada Executive Officer Leadership in Financial Supervision Ilhom Abdulloev Executive Director Open Society Institute Tajikistan Assistance Foundation - Tajikistan Mohammed Abdulmawjoo Director The Engineering Association Iraq d for Development & Environment Kassim Abdulsalam Zonal Coordinator/Field Strength in Diversity Nigeria Executive Development Centre, Nigeria and Farmers Advocacy and Support Initiative in Nig Serena Abi Khalil Research and Program Arab NGO Network for Lebanon Officer Development (ANND) Kjetil Abildsnes Senior Adviser, Economic Norwegian Church Aid (NCA) Norway Justice Maria Victoria Abreu Lugar Program Manager Global Foundation for Dominican Democracy and Development Republic (GFDD) Edmond Abu Executive Director Native Consortium & Research Sierra Leone Center Mohammed Abu-Nimer Senior Advisor KAICIID Dialogue Centre United States Aouadi Achraf Founder I WATCH Tunisia Terica Adams Executive Director Hamilton National Dance Day United States Inc. Laurel Adams Chief Executive Officer Women for Women United States International Zoë Adams Executive Director The Strongheart Group United States BAKINAM ADAMU C E O Organization for Research and Ghana Community Development Ghana -

Nthole Matela Skebza D 8 Nameless

namelessnameless IssueIssue 2 2 • • January January 2015 2015 NTHOLENTHOLE MATELAMATELA USINGUSING BEAUTY BEAUTY FOR FOR AA GOOD GOOD CAUSE CAUSE PlusPlus 88 MISTAKESMISTAKES TO TO AVOID AVOID ININ A A NE NEWW RELATIONSHIP RELATIONSHIP MONEY TALK: MONEYEscape TALK:the Rat Races SKEBZA D Escape the Rat Races SKEBZA D Romance at the Gym? REACTIONREACTION SHOCKED SHOCKED ME ME Romance at the Gym? CHILDCHILD CIRCUMCISION: CIRCUMCISION: IS IS IT IT W Worthorth THE THE pain pain AND AND health health RISKS RISKS MOM MOM AND AND dad dad?? Nameless Magazine • www.facebook.com/namelessmag • 1 Features 04 Nthole Matela Using beauty for a good cause. 08 Skebza D Fan reaction shocked me. 10 Financial Focus Escape the Rat race FROM THE EDITOR 12 Child Circumcision Editor In Chief Should parents make a lifetime decision for their A month in to the new year, resolutions still very much fresh in our Limpho Liphoto kids? minds as we chase different goals to become better human beings 14 Mafa Monyalotsa in all spheres of life. To keep the spirit going, we feature the current Writers A new member to the Nameless team, Civil face of Lesotho title holder, Miss Nthole Matela who is proof that Tiisetso Khants’e Monare Engineer and owner of Iris Images . dreams are possible with belief and action. She just came back from representing Lesotho at the Miss World 2014 competition. 16 Mahlape Moeletsi Tankiso Moea Just finding her feet in life and modeling January is a time that most people dread as far as finances are con- Poets 18 Project S.M.I.L.E Lives up to its name cerned, having enjoyed all the pleasures of life in the festive season Masako Lily Lekhanya Youth pushing for change . -

Adolescence: an Age of Opportunity of Age an Adolescence

THE STATE OF THE WORLD’S CHILDREN United Nations Children’s Fund 3 United Nations Plaza THE STATE OF THE WORLD’S CHILDREN 2011 New York, NY 10017, USA Email: [email protected] Website: www.unicef.org 2011 ADOLESCENCE: AN AGE OF OPPORTUNITY Adolescence US $25.00 ISBN: 978-92-806-4555-2 Sales no.: E.11.XX.1 An Age of Opportunity Scan this QR code or go to the © United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) UNICEF publications website February 2011 www.unicef.org/publications Photo Credits Chapter opening photos Chapter 3 – (pages 42–59)* Chapter 1: © UNICEF/NYHQ2009-2036/Sweeting © UNICEF/NYHQ2005-2242/Pirozzi Chapter 2: © UNICEF/BANA2006-01124/Munni © UNICEF/NYHQ2005-1781/Pirozzi Chapter 3: © UNICEF/NYHQ2009-2183/Pires © UNICEF/NYHQ2006-2506/Pirozzi Chapter 4: © UNICEF/MLIA2009-00317/Dicko © UNICEF/NYHQ2006-1440/Bito © UNICEF/AFGA2009-00958/Noorani Chapter 1 – (pages 2–15)* © UNICEF/NYHQ2009-1021/Noorani © UNICEF/NYHQ2009-1811/Markisz © UNICEF/NYHQ2004-0739/Holmes © UNICEF/NYHQ2009-1416/Markisz © UNICEF/NYHQ2010-0260/Noorani Chapter 4 – (pages 62–77)* © UNICEF/NYHQ2007-0359/Thomas © UNICEF/NYHQ2007-1753/Nesbitt © UNICEF/PAKA2008-1423/Pirozzi © UNICEF/NYHQ2004-1027/Pirozzi © UNICEF/NYHQ2009-0970/Caleo © UNICEF/NYHQ2008-0573/Dean © UNICEF/MENA00992/Pirozzi © UNICEF/NYHQ2005-1809/Pirozzi © US Fund for UNICEF/Discover the Journey Chapter 2 – (pages 18–39)* © UNICEF/NYHQ2007-2482/Noorani © UNICEF/NYHQ2009-2213/Khemka © UNICEF/NYHQ2006-0725/Brioni © UNICEF/NYHQ2009-2297/Holt © UNICEF México/Beláustegui *Photo credits are not included for Perspectives, Adolescent voices and Technology panels. © United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) United Nations Children’s Fund February 2011 3 United Nations Plaza UNICEF Offices UNICEF The Americas and Caribbean New York, NY 10017, USA Regional Office Permission to reproduce any part of this publication is required. -

Global Employment Trends for Youth 2020

Global Employment Trends for Youth 2020 2020 for Youth Trends Employment Global – Technology and the future of jobs of future the and – Technology X Global Employment Trends for Youth 2020 Technology and the future of jobs X Global Employment Trends for Youth 2020 Technology and the future of jobs International Labour Office Geneva Copyright © International Labour Organization 2020 First published 2020 Publications of the International Labour Office enjoy copyright under Protocol 2 of the Universal Copyright Convention. Nevertheless, short excerpts from them may be reproduced without authorization, on condition that the source is indicated. For rights of reproduction or translation, application should be made to ILO Publications (Rights and Licensing), International Labour Office, CH-1211 Geneva 22, Switzerland, or by email: [email protected]. The International Labour Office welcomes such applications. Libraries, institutions and other users registered with reproduction rights organizations may make copies in accordance with the licences issued to them for this purpose. Visit www.ifrro.org to find the reproduction rights organization in your country. Global Employment Trends for Youth 2020: Technology and the future of jobs International Labour Office – Geneva: ILO, 2020 ISBN 978-92-2-133505-4 (print) ISBN 978-92-2-133506-1 (web pdf) youth employment / youth unemployment / labour market analysis / labour force participation / employment policy / developed countries / developing countries / future of work 13.01.3 The designations employed in ILO publications, which are in conformity with United Nations practice, and the presentation of material therein do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the International Labour Office concerning the legal status of any country, area or terri- tory or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers. -

Levels and Trends in Child Mortality (UN IGME), Report 2020

Levels & Trends in Report 2020 Child Estimates developed by the UN Inter-agency Group for Mortality Child Mortality Estimation United Nations This report was prepared at UNICEF headquarters by David Sharrow, Lucia Hug, Yang Liu, and Danzhen You on behalf of the United Nations Inter-agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation (UN IGME). Organizations and individuals involved in generating country-specific estimates of child mortality (Individual contributors are listed alphabetically.) United Nations Children’s Fund Lucia Hug, Sinae Lee, Yang Liu, Anupam Mishra, David Sharrow, Danzhen You World Health Organization Bochen Cao, Jessica Ho, Kathleen Louise Strong World Bank Group Emi Suzuki United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division Kirill Andreev, Lina Bassarsky, Victor Gaigbe-Togbe, Patrick Gerland, Danan Gu, Sara Hertog, Nan Li, Thomas Spoorenberg, Philipp Ueffing, Mark Wheldon United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean, Population Division Guiomar Bay, Helena Cruz Castanheira Special thanks to the Technical Advisory Group of the UN IGME for providing technical guidance on methods for child mortality estimation Leontine Alkema, University of Massachusetts, Amherst Kenneth Hill (Chair), Stanton-Hill Research Robert Black, Johns Hopkins University Bruno Masquelier, University of Louvain Simon Cousens, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine Colin Mathers, University of Edinburgh Trevor Croft, The Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) Program, ICF Jon Pedersen, Mikro! Michel Guillot, University of Pennsylvania and French Institute for Jon Wakefield, University of Washington Demographic Studies (INED) Neff Walker, Johns Hopkins University Special thanks to the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), including William Weiss and Robert Cohen, and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, including Kate Somers and Savitha Subramanian, for supporting UNICEF’s child mortality estimation work.