Merciful Justice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WALLACE, (Richard Horatio) Edgar Geboren: Greenwich, Londen, 1 April 1875

WALLACE, (Richard Horatio) Edgar Geboren: Greenwich, Londen, 1 april 1875. Overleden: Hollywood, USA, 10 februari 1932 Opleiding: St. Peter's School, Londen; kostschool, Camberwell, Londen, tot 12 jarige leeftijd. Carrière: Wallace was de onwettige zoon van een acteur, werd geadopteerd door een viskruier en ging op 12-jarige leeftijd van huis weg; werkte bij een drukkerij, in een schoen- winkel, rubberfabriek, als zeeman, stukadoor, melkbezorger, in Londen, 1886-1891; corres- pondent, Reuter's, Zuid Afrika, 1899-1902; correspondent, Zuid Afrika, London Daily Mail, 1900-1902 redacteur, Rand Daily News, Johannesburg, 1902-1903; keerde naar Londen terug: journalist, Daily Mail, 1903-1907 en Standard, 1910; redacteur paardenraces en later redacteur The Week-End, The Week-End Racing Supplement, 1910-1912; redacteur paardenraces en speciaal journalist, Evening News, 1910-1912; oprichter van de bladen voor paardenraces Bibury's Weekly en R.E. Walton's Weekly, redacteur, Ideas en The Story Journal, 1913; schrijver en later redacteur, Town Topics, 1913-1916; schreef regelmatig bijdragen voor de Birmingham Post, Thomson's Weekly News, Dundee; paardenraces columnist, The Star, 1927-1932, Daily Mail, 1930-1932; toneelcriticus, Morning Post, 1928; oprichter, The Bucks Mail, 1930; redacteur, Sunday News, 1931; voorzitter van de raad van directeuren en filmschrijver/regisseur, British Lion Film Corporation. Militaire dienst: Royal West Regiment, Engeland, 1893-1896; Medical Staff Corps, Zuid Afrika, 1896-1899; kocht zijn ontslag af in 1899; diende bij de Lincoln's Inn afdeling van de Special Constabulary en als speciaal ondervrager voor het War Office, gedurende de Eerste Wereldoorlog. Lid van: Press Club, Londen (voorzitter, 1923-1924). Familie: getrouwd met 1. -

Imagine Language & Literacy Leveled Books Grade 3 (All Printouts)

Reading Comprehension Leveled Books Guide About Leveled Books Imagine Learning’s Leveled Books provide literary and informational texts in a variety of genres at each reading level. Leveled books include narratives, myths, and plays, as well as biographies and informational texts that teach content from math, science, and social studies. Selections are paired: one text provides background knowledge for the other. Reading levels are determined by Lexile measures, and books are grouped into grades based on target Lexile measurements for each grade. The Leveled Book resources that support reading comprehension are: • Leveled Book Texts and Comprehension Questions • Graphic Organizers • Reading Response Journals Leveled Book Texts and Comprehension Questions Resource Overview Leveled Book Texts are printouts of the book cover and text. Each printout includes information for a thematically paired Leveled Book, Lexile measurement, and word count. Each Leveled Book text also includes an Oral Reading Fluency assessment box to evaluate students’ oral reading ability. Comprehension Question types for leveled books include literal, inferential, vocabulary, main idea, story map, author’s purpose, intertextual, cause/effect, compare/contrast, and problem/solution. Each Comprehension Question sheet also includes vocabulary and glossary words used in the books. Answers to questions are located in the Leveled Books Answer Key. How to Use This Resource in the Classroom Whole class or small group reading • Conduct a shared reading experience, inviting individual students to read segments of the story aloud. • After reading a selection together, call on volunteers to connect the story to a personal experience, comment on his or her favorite part, or share what he or she has learned from the reading. -

Lessons from the Cellblock: a Study of Prison Inmate Participants in an Alternatives to Violence Program

Lessons from the Cellblock: A Study of Prison Inmate Participants in an Alternatives to Violence Program Stanton D. Sloane Submitted for: EDMP 615 Professor Paul Salipante Introduction This paper is a follow-on to preliminary research on the Quakers conducted in the fall of 2000. That inquiry looked at other-regarding principles in the Quaker religion and how they are applied in practice. Underlying Quakerism is a deep regard for all people. The Quakers believe that “God is in everyone.” They are strongly anti-violent, very receptive of people of other faiths, and generally very tolerant in their approach to life. Because of these principles, Quakers are frequently sought out as mediators, counselors, and leaders of organizations committed to non-violence. The strength of their beliefs about the goodness of all other people led me to the notion that this principle might be transferable and useful as a means of fostering cooperation. It seemed logical that the degree to which one person regards another would have a bearing on his or her willingness to cooperate. If other-regarding/other-valuing (I will use these terms together frequently throughout this paper) can be instilled and reinforced in people and their willingness to cooperate subsequently shown to increase, then we should be able to draw the conclusion that modifying these values produces a positive effect on cooperation. My theory is that it does, and I will present an analysis that supports this conclusion herein. A second, and more difficult question, is whether or not the other-regarding behavior can be generalized across a broader segment of the population (beyond the immediate group). -

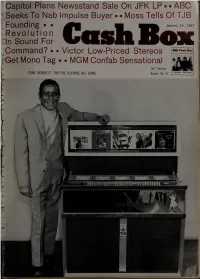

Command? • Victor Low-Priced Stereos Get Mono Tag • MGM Confab Sensational

Capitol Plans Newsstand Sale On JFK LP**ABC ' Seeks To Nab Impulse Buyer • • Moss Tells Of TJB Founding • • January 14, 1967 Revolution In Sound For Command? • Victor Low-Priced Stereos Get Mono Tag • MGM Confab Sensational Int’l Section TONY BENNETT: THEY’RE PLAYING HIS SONG Begins Pg. 47 Straight from the Byrds'mouths. “SoJou Want to Be ” ’n’RollStar aRocka w 4-43987 \Everybody’s Been Burned Wingding albums byThe Byrds... v rik. srAvtmAn COLUMBIA:® MARCAS REG. PRINTED IN US.A. * S te f e O J, EIGHT MILES * HIGH - so < *. , HEY JOE WHAT’S HAPPENING?)?! CAPTAIN SOUL AND MORE CL 2549/ CS 9349* Where the soaring action is. On COLUMBIA RECORDS® CashBox Vol. XXVI 1 1— Number 26 January 14, 1967 (Publication Office) 1780 Broadway New York, N. Y. 10019 (Phone: JUdson 6-2640) CABLE ADDRESS: CASHBOX, N. Y. JOE ORLECK Chairman of the Board GEORGE ALBERT President and Publisher NORMAN ORLECK Executive Vice President The Fast Start MARTY OSTROW Vice President LEON SCHUSTER Treasurer IRV LICHTMAN Editor in Chief EDITORIAL TOM McENTEE Associate Editor If a favorite business lunch part- can instill confidence on levels of the ALLAN DALE EDITORIAL ASSISTANTS ner begs off for a date-yet-to- business. Of course, the consumer MIKE MARTUCCI JERRY ORLECK be-announced; if a label exec’s secre- doesn’t really care what kind of year a BERNIE BLAKE label has had, is having or will have. Director oj Advertising tary informs you that “I’m sorry, he’s ACCOUNT EXECUTIVES He’ll be glad to oblige a label with suc- out of town,” don’t fret. -

Book, International Mo- Tion Picture Almanac, the Television Almanac Will Continue to Serve a Vital Need

eA11801ad 0 swoisnoaasn N3HMXIddtfN c:,-) 0% ineneh 04 ' C) 40z GEM ) %.0 4Pt 10 PRIORITY® etzw tfiea.0 ot ce. ct *MAIL* COM I'MUNITEDPOSTAL SERVICE® STATES PRIORITy®*MAIL* USPSDATE TRACKINGTMOF DELIVERY INCLUDED* SPECIFIED" $ INSURANCEPICKUP AVAILABLE INCLUDED + HOLLYWOOD TECHNICOLOR PLANT 20.The new Technicolor laboratorydevoted exclusively to film processing of television shows andcommercials.Roundthe clock service geared to your air dates. TECHNICOLOR VIDTRONICS.Transfer of color or black and white video tape to film with Technicolor quality. The uniqueTechnicolor combination of electronic image transfer and imbibition printmanufacture provide filmsof top television quality. Vidtronics Division, 823 NorthSeward, Hollywood, California. OVERSEAS TECHNICOLOR LTD. Technicolorprecisionservicesare available overseas through the facilitiesofTechnicolor Limited, Bath Road, Harmondsworth, West Drayton, Middlesex, England. TELEVISIONTechnicolc:sr® HOLLYWOOD LONDON The Greatest Name in Color Television 2 c 0 C 0 mC -a z > --1 0 > Z 331. < n n 0"n > m x m 2 E 5 03 n o rr -4 m rn c z 23 rn n 0 1- ° _ .,.,IT O u rn "n O m * 0 ,?,,f% "till I, .14 1;-- ; -dc f - Virtually all prime -time TV isnow in color. Stations and sponsors want their feature films in color, too. So, shoot in color for greater impact in the theater today and for greater TV potentialtomorrow. Shoot in color... you'll show a greater profit. For excellence in color, look to Eastman Kodak experience, always and immediately availablethrough the Eastman sales and engineeringrepresentatives. Motion Picture and Education Markets Division EASTMAN KODAK COMPANY New York: 200 Park Ave. 212 MU 7.7080 Chicago: 130 East Randolph Dr 312.236-7234 Hollywood: 15677 Santa Monica Blvd. -

Revolutionary Letters © 1971, 1974, 1979, 2005 Diane Di Prima

Last Gasp of San Francisco 2005 Revolutionary Letters © 1971, 1974, 1979, 2005 Diane di Prima Published and Distributed by Last Gasp of San Francisco 777 Florida Street San Francisco, CA 94110 www.lastgasp.com email: [email protected] ISBN 0-86719-538-X Fifth expanded edition, September 2005 Printed in Hong Kong Cover Design by Tara Marlowe Thank you to Sara Larsen for her assistance. World Rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, xerography, scanning, or any information storage or retrieval system, without the prior permission in writing of the author or publisher. The REVOLUTIONARY LETTERS are dedicated to Bob Dylan; and to my grandfather, Domenico Mallozzi, friend of the great anarchist dreamers of his time, who read me Dante at the age of four & named my mother after Emma Goldman. 5 APRIL FOOL BIRTHDAY POEM FOR GRANDPA Today is your birthday and I have tried writing these things before, but now in the gathering madness, I want to thank you for telling me what to expect for pulling no punches, back there in that scrubbed Bronx parlor thank you for honestly weeping in time to innumerable heartbreaking italian operas for pulling my hair when I pulled the leaves off the trees so I’d know how it feels, we are involved in it now, revolution, up to our knees and the tide is rising, I embrace strangers on the street, filled with their love and mine, the love you told us had to come or we die, told them all in that Bronx -

Complete Dissertation.Pdf

VU Research Portal God Remembers Pakpahan, B.J. 2011 document version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication in VU Research Portal citation for published version (APA) Pakpahan, B. J. (2011). God Remembers: Towards a Theology of Remembrance as a Basis of Reconciliation in Communal Conflict. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. E-mail address: [email protected] Download date: 01. Oct. 2021 VRIJE UNIVERSITEIT God Remembers Towards a Theology of Remembrance as a Basis of Reconciliation in Communal Conflict ACADEMISCH PROEFSCHRIFT ter verkrijging van de graad Doctor aan de Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, op gezag van de rector magnificus prof.dr. L.M. Bouter, in het openbaar te verdedigen ten overstaan van de promotiecommissie van de faculteit der Godgeleerdheid op dinsdag 20 december 2011 om 11.45 uur in de aula van de universiteit, De Boelelaan 1105 door Binsar Jonathan Pakpahan geboren te Medan, Indonesië promotoren: prof.dr. -

COMPLETE FILM NOIR (1940 Thru 1965)

COMPLETE FILM NOIR (1940 thru 1965) Page 1 of 15 CONSENSUS FILM NOIR (1940 thru 1959) (1960-1965) The idea for a COMPLETE FILM NOIR LIST came to me when I realized that I was “wearing out” a then recently purchased copy of the Film Noir Encyclopedia, 3rd edition. My initial plan was to make just a list of the titles listed in this reference so I could better plan my film noir viewing on AMC (American Movie Classics). Realizing that this plan was going to take some keyboard time, I thought of doing a search on the Internet Movie DataBase (here after referred to as the IMDB). By using the extended search with selected criteria, I could produce a list for importing to a text editor. Since that initial list was compiled over ten years ago, I have added additional reference sources, marked titles released on NTSC laserdisc and NTSC Region 1 DVD formats. When a close friend complained about the length of the list as it passed 600 titles, the idea of producing a subset list of CONSENSUS FILM NOIR was born. Several years ago, a DVD producer wrote me as follows: “I'd caution you not to put too much faith in the film noir guides, since it's not as if there's some Film Noir Licensing Board that reviews films and hands out Certificates of Authenticity. The authors of those books are just people, limited by their own knowledge of and access to films for review, so guidebooks on noir are naturally weighted towards the more readily available studio pictures, like Double Indemnity or Kiss Me Deadly or The Big Sleep, since the many low-budget B noirs from indie producers or overseas have mostly fallen into obscurity.” There is truth in what the producer says, but if writers of (film noir) guides haven’t seen the films, what chance does an ordinary enthusiast have. -

Supplementary Materials: the Magic Drum, the Squire's Bride, the Fool of the World and the Flying Ship; the Cat Who Walked by Himself, the Story of Keesh

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 075 852 24 CS 200 510 TITLE Drama Curriculum--V and VI [Grades Five anal Six], Teacher's Guides; Supplementary Materials: The Magic Drum, The Squire's Bride, The Fool of the World and The Flying Ship; The Cat Who Walked by Himself, The Story of Keesh. INSTITUTION Oregon Univ., Eugene. Oregon Elementary English Project. SPONS AGENCY Office of Education (DREW), Washington, D.C. Bureau of Research. BUREAU NO BR-8-0143 PUB DATE 71 CONTRACT OEC-0-8-080143-3701 NOTE 240p. AVAILABLE FROMAccompanying reel-to-reel tapes only available on loan by written request from ERIC Clearinghouse on Reading and Communication Skills, NCTE, 1111 Kenyon Rd., Urbana, Ill. 61801, Attention Documents Coordinator EDRS PRICE MF-$0.65 HC-$9.87 DESCRIPTORS Acting; Composition (Literary); *Curriculum Guides; *Drama; *Dramatic Play; Dramatics; Elementary Education; English; *Grade 5: *Grade 6; Literary Analysis; Pantomime; Playwr"ting; Sensory Experience; Skits; Theater Arts IDENTIFIERS *Oregon Elementary English Project ABSTRACT These curriculum guides are designed to introduce drama to students at the fifth and sixth grade level. The teacher's guide for each of the two grade levels presents 41 lessons. Each lesson includes a description of objectives and various exercises, including movement warm-ups, concentration warm-ups, descriptions of the character type to be acted, pantomime exercises, composition exercises, and other activities designed to meet the objectives. Some of the lessons require various physical objects and other materials, such as a prop box, a tape recorder, play scripts, ox music. Suggested plays for class discussion and dramatization included with the teacher's guides are: "The Cat That Walked by Himself," "The Story of Keesh," "The Magic Drum," "The Squire's Bride," and "The Fool of the World." Eight demonstration tapes to accompany' nine of the lessons are included.