Time, History, and Memory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

*For All Comprehensive Exam Sections, DO NOT Attempt Answering a Question Unless You Really Know the Answer

*For all comprehensive exam sections, DO NOT attempt answering a question unless you really know the answer. You will be much less likely to pass if you provide information that does not actually address a question (even if the information you provide is technically accurate, and could be used to answer another question). Also, most questions (except Statistics) will require you to cite original sources to support your arguments, but please do not cite a textbook. Cognition and Learning Section This exam is tied most directly to PSY 620 and 621. You are not allowed to attempt this exam until you have passed both of these courses. You will see questions covering such topics as (in no particular order of importance): perception, attention, working memory, episodic versus semantic versus procedural long- term memory, implicit versus explicit memory, automatic versus controlled processing, categorization, social cognition, metacognition, theories of learning and behavior, eyewitness memory, language, decision-making and problem-solving, expertise, and developmental/age issues concerning memory. By far the most important thing to study is an undergraduate textbook in cognitive psychology (e.g., Goldstein; Reisberg; Robinson-Riegler; Sternberg), as well as notes and materials from PSY 620. Below is an example question (no longer used) with a good student response. It will give you an idea of the level of detail needed for a good response, and how to cite original sources to support your statements. You are an eyewitness to a crime in which a man robs a liquor store. He does so in under 5 minutes while pointing a gun at the clerk, is not wearing a mask or anything else to hide his face, and he quickly runs away after the robbery. -

Geological Timeline

Geological Timeline In this pack you will find information and activities to help your class grasp the concept of geological time, just how old our planet is, and just how young we, as a species, are. Planet Earth is 4,600 million years old. We all know this is very old indeed, but big numbers like this are always difficult to get your head around. The activities in this pack will help your class to make visual representations of the age of the Earth to help them get to grips with the timescales involved. Important EvEnts In thE Earth’s hIstory 4600 mya (million years ago) – Planet Earth formed. Dust left over from the birth of the sun clumped together to form planet Earth. The other planets in our solar system were also formed in this way at about the same time. 4500 mya – Earth’s core and crust formed. Dense metals sank to the centre of the Earth and formed the core, while the outside layer cooled and solidified to form the Earth’s crust. 4400 mya – The Earth’s first oceans formed. Water vapour was released into the Earth’s atmosphere by volcanism. It then cooled, fell back down as rain, and formed the Earth’s first oceans. Some water may also have been brought to Earth by comets and asteroids. 3850 mya – The first life appeared on Earth. It was very simple single-celled organisms. Exactly how life first arose is a mystery. 1500 mya – Oxygen began to accumulate in the Earth’s atmosphere. Oxygen is made by cyanobacteria (blue-green algae) as a product of photosynthesis. -

Collective Memory from a Psychological Perspective

Review Collective Memory from a Psychological Perspective 1, 2 3 William Hirst, * Jeremy K. Yamashiro, and Alin Coman Social scientists have studied collective memory for almost a century, but psy- Highlights chological analyses have only recently emerged. Although no singular approach Collective memories can involve small communities, such as couples, to the psychological study of collective memory exists, research has largely: (i) families, or neighborhood associa- exploredthe social representations of history, including generational differences; tions, or large communities, such as nations, the world-wide congregation (ii) probed for the underlying cognitive processes leading to the formation of of Catholics, or terrorist groups such collective memories, adopting either a top-down or bottom-up approach; and (iii) as ISIS. They bear on the collective explored how people live in history and transmit personal memories of historical identity of the community. importance acrossgenerations.Here,wediscussthesedifferent approaches and Many studies focus on either the repre- highlight commonalities and connections between them. sentation of extant collective memories or the formation and retention of either extant or new collective memories. Memories Held Across a Community Members of a community often share similar memories: Germans know that their country Those interested in the formation of participated in the mass murder of Jews; Catholics, that Jesus fasted for 40 days; and a family, collective memories can approach ’ that grandfather immigrated from Ireland. Such collective memories can shape a community s the topic in a top-down or bottom- up fashion. ’ identity and its actions. Germany s struggles to come to terms with its troublesome past, for fi instance, de ne to a great extent how Germans see themselves today as Germans [1]. -

How Big Is Human Memory, Or on Being Just Useful Enough

Downloaded from learnmem.cshlp.org on September 29, 2021 - Published by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press REVIEW Yadin Dudai How Big Is Human Memory, Department of Neur0bi010gy or On Being Just Useful Enough The Weizmann Institute of Science Reh0v0t 76100 Israel We are, in many respects, what we remember. But how much do we do? So far, science has provided only a very partial answer to this riddle. The magical number seven, plus or minus two, seems to constrain the capacity of our immediate memory (Miller 1956). But surely its constraints dissipate when memories settle in long-term stores. Yet how big are these stores? If we combine all of our factual knowledge and personal reminiscence, childhood scenes and memories of the past day, intimate experiences and professional expertisemhow many items are there, that, combined together, mold us into unique individuals? The answer is not simple, and neither is the question. For example, what is an item in long-term memory? And how can we measure it, being sure that we unveil memory capacity and not merely the occasional ability to tap it? Such theoretical and practical difficulties, no doubt, have contributed to the fact that the capacity of human memory is still an enigma. Yet, despite the inherent and undeniable complexities, the issue deserves to be retrieved, once in a while, from the oblivions of the collective memory of the scientific community. (For a selection of earlier discussions of the size of human long-term memory, see Galton 1879; Landauer 1986; Crovitz et al. 1991.) Folk Psychology and When confronted with the issue, many tend to provide an intuitive Early Views estimate of the size of their memory, based either on belief or introspection or both. -

Collective Memory from a Psychological Perspective

Int J Polit Cult Soc (2009) 22:125–141 DOI 10.1007/s10767-009-9057-9 Collective Memory from a Psychological Perspective Alin Coman & Adam D. Brown & Jonathan Koppel & William Hirst Published online: 26 May 2009 # Springer Science + Business Media, LLC 2009 Abstract The study of collective memory has burgeoned in the last 20 years, so much so that one can even detect a growing resistance to what some view as the imperialistic march of memory studies across the social sciences (e.g., Berliner 2005;Fabian1999). Yet despite its clear advance, one area that has remained on the sidelines is psychology. On the one hand, this disinterest is surprising, since memory is of central concern to psychologists. On the other hand, the relative absence of the study of collective memory within the discipline of psychology seems to suit both psychology and other disciplines of the social sciences, for reasons that will be made clear. This paper explores how psychology might step from the sidelines and contribute meaningfully to discussions of collective memory. It reviews aspects of the small literature on the psychology of collective memoryandconnectsthisworktothelargerscholarly community’sinterestincollectivememory. Keywords Social contagion . Memory restructuring . Collective memory . Collective forgetting General Comments Contextualizing the Study of Collective Memory Why not has psychology figured prominently in discussions of collective memory? For those in social science fields other than psychology, the methodological individualism of The first three authors contributed equally to this paper. The order in which they are listed reflects the throw of a die. A. Coman : J. Koppel : W. Hirst (*) The New School for Social Research, New York, NY 10011, USA e-mail: [email protected] A. -

Pioneers in Optics: Christiaan Huygens

Downloaded from Microscopy Pioneers https://www.cambridge.org/core Pioneers in Optics: Christiaan Huygens Eric Clark From the website Molecular Expressions created by the late Michael Davidson and now maintained by Eric Clark, National Magnetic Field Laboratory, Florida State University, Tallahassee, FL 32306 . IP address: [email protected] 170.106.33.22 Christiaan Huygens reliability and accuracy. The first watch using this principle (1629–1695) was finished in 1675, whereupon it was promptly presented , on Christiaan Huygens was a to his sponsor, King Louis XIV. 29 Sep 2021 at 16:11:10 brilliant Dutch mathematician, In 1681, Huygens returned to Holland where he began physicist, and astronomer who lived to construct optical lenses with extremely large focal lengths, during the seventeenth century, a which were eventually presented to the Royal Society of period sometimes referred to as the London, where they remain today. Continuing along this line Scientific Revolution. Huygens, a of work, Huygens perfected his skills in lens grinding and highly gifted theoretical and experi- subsequently invented the achromatic eyepiece that bears his , subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at mental scientist, is best known name and is still in widespread use today. for his work on the theories of Huygens left Holland in 1689, and ventured to London centrifugal force, the wave theory of where he became acquainted with Sir Isaac Newton and began light, and the pendulum clock. to study Newton’s theories on classical physics. Although it At an early age, Huygens began seems Huygens was duly impressed with Newton’s work, he work in advanced mathematics was still very skeptical about any theory that did not explain by attempting to disprove several theories established by gravitation by mechanical means. -

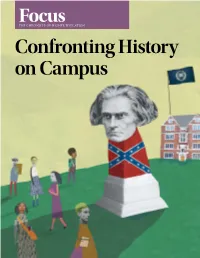

Confronting History on Campus

CHRONICLEFocusFocus THE CHRONICLE OF HIGHER EDUCATION Confronting History on Campus As a Chronicle of Higher Education individual subscriber, you receive premium, unrestricted access to the entire Chronicle Focus collection. Curated by our newsroom, these booklets compile the most popular and relevant higher-education news to provide you with in-depth looks at topics affecting campuses today. The Chronicle Focus collection explores student alcohol abuse, racial tension on campuses, and other emerging trends that have a significant impact on higher education. ©2016 by The Chronicle of Higher Education Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, forwarded (even for internal use), hosted online, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other noncommercial uses permitted by copyright law. For bulk orders or special requests, contact The Chronicle at [email protected] ©2016 THE CHRONICLE OF HIGHER EDUCATION INC. TABLE OF CONTENTS OODROW WILSON at Princeton, John Calhoun at Yale, Jefferson Davis at the University of Texas at Austin: Students, campus officials, and historians are all asking the question, What’sW in a name? And what is a university’s responsibil- ity when the name on a statue, building, or program on campus is a painful reminder of harm to a specific racial group? Universities have been grappling anew with those questions, and trying different approaches to resolve them. Colleges Struggle Over Context for Confederate Symbols 4 The University of Mississippi adds a plaque to a soldier’s statue to explain its place there. -

Richard Dawkins

RICHARD DAWKINS HOW A SCIENTIST CHANGED THE WAY WE THINK Reflections by scientists, writers, and philosophers Edited by ALAN GRAFEN AND MARK RIDLEY 1 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford ox2 6dp Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries Published in the United States by Oxford University Press Inc., New York © Oxford University Press 2006 with the exception of To Rise Above © Marek Kohn 2006 and Every Indication of Inadvertent Solicitude © Philip Pullman 2006 The moral rights of the authors have been asserted Database right Oxford University Press (maker) First published 2006 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should -

The Spindle Assembly Checkpoint and Speciation

The spindle assembly checkpoint and speciation Robert C. Jackson1 and Hitesh B. Mistry2 1 Pharmacometrics Ltd., Cambridge, United Kingdom 2 Division of Pharmacy, University of Manchester, Manchester, United Kingdom ABSTRACT A mechanism is proposed by which speciation may occur without the need to postulate geographical isolation of the diverging populations. Closely related species that occupy overlapping or adjacent ecological niches often have an almost identical genome but differ by chromosomal rearrangements that result in reproductive isolation. The mitotic spindle assembly checkpoint normally functions to prevent gametes with non-identical karyotypes from forming viable zygotes. Unless gametes from two individuals happen to undergo the same chromosomal rearrangement at the same place and time, a most improbable situation, there has been no satisfactory explanation of how such rearrange- ments can propagate. Consideration of the dynamics of the spindle assembly checkpoint suggest that chromosomal fission or fusion events may occur that allow formation of viable heterozygotes between the rearranged and parental karyotypes, albeit with decreased fertility. Evolutionary dynamics calculations suggest that if the resulting heterozygous organisms have a selective advantage in an adjoining or overlapping ecological niche from that of the parental strain, despite the reproductive disadvantage of the population carrying the altered karyotype, it may accumulate sufficiently that homozygotes begin to emerge. At this point the reproductive disadvantage of the rearranged karyotype disappears, and a single population has been replaced by two populations that are partially reproductively isolated. This definition of species as populations that differ from other, closely related, species by karyotypic changes is consistent with the classical definition of a species as a population that is capable of interbreeding to produce fertile progeny. -

The Selfish Gene by Richard Dawkins Is Another

BOOKS & ARTS COMMENT ooks about science tend to fall into two categories: those that explain it to lay people in the hope of cultivat- Bing a wide readership, and those that try to persuade fellow scientists to support a new theory, usually with equations. Books that achieve both — changing science and reach- ing the public — are rare. Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species (1859) was one. The Selfish Gene by Richard Dawkins is another. From the moment of its publication 40 years ago, it has been a sparkling best-seller and a TERRY SMITH/THE LIFE IMAGES COLLECTION/GETTY SMITH/THE LIFE IMAGES TERRY scientific game-changer. The gene-centred view of evolution that Dawkins championed and crystallized is now central both to evolutionary theoriz- ing and to lay commentaries on natural history such as wildlife documentaries. A bird or a bee risks its life and health to bring its offspring into the world not to help itself, and certainly not to help its species — the prevailing, lazy thinking of the 1960s, even among luminaries of evolution such as Julian Huxley and Konrad Lorenz — but (uncon- sciously) so that its genes go on. Genes that cause birds and bees to breed survive at the expense of other genes. No other explana- tion makes sense, although some insist that there are other ways to tell the story (see K. Laland et al. Nature 514, 161–164; 2014). What stood out was Dawkins’s radical insistence that the digital information in a gene is effectively immortal and must be the primary unit of selection. -

The God Delusion: a Worldview Analysis Bill Martin Cornerstone Church of Lakewood Ranch - August 6, 2008

The God Delusion: A Worldview Analysis Bill Martin Cornerstone Church of Lakewood Ranch - August 6, 2008 Richard Dawkins, Charles Simonyi Professor of the Public Understanding of Science at Oxford University “The God Delusion really marked the point where Dawkins transformed from the professor holding the Charles Simonyi Chair for the Public Understanding of Science to the celebrity fundamentalist atheist.” - Carl Packman, “An Evangelical Atheist” in New Statesman, 8.5.08 The Selfish Gene, Oxford University Press, 1976 The Extended Phenotype, Oxford University Press, 1982 The Blind Watchmaker, W. W. Norton & Company, 1986 River out of Eden, Basic Books, 1995 Climbing Mount Improbable, New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1996 Unweaving the Rainbow, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1998 A Devil's Chaplain, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2003 The Ancestor's Tale, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2004 The God Delusion, Bantam Books, 2006 / Bill’s edition: Mariner Books; 1 edition (January 16, 2008) Ad hominem - attacking an opponent's character rather than answering his argument Outline of Bill’s Talking Points 1. General Summary 2. Two Worldview Presuppositions 3. Personal Reflections and Lessons Resources: Books and Journals Aikman, David. The Delusion of Disbelief. Nashville: Tyndale House, 2008. McGrath, Alister. The Dawkins Delusion? Downers Grove: InterVarsity Press, 2007. _______. Dawkins’ God: Genes, Memes and the Meaning of Life. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2005. Ganssle, Gregory E. “Dawkins’s Best Argument: The Case against God in The God Delusion,” Philosophia Christi , 2008,Volume 10, Number 1, pp. 39-56. Plantinga, Alvin. “The Dawkins Confusion,” Books & Culture, March/April 2007, Vol. 13, No. 2, Page 21. The Duomo Pieta (Florence, Italy) Reviews of The God Delusion “dogmatic, rambling and self-contradictory” - Andrew Brown in Prospect “he risks destroying a larger target”- Jim Holt in The New York Times “I'm forced, after reading his new book, to conclude he's actually more an amateur.” - H. -

Memory in Mind and Culture

This page intentionally left blank Memory in Mind and Culture This text introduces students, scholars, and interested educated readers to the issues of human memory broadly considered, encompassing individual mem- ory, collective remembering by societies, and the construction of history. The book is organized around several major questions: How do memories construct our past? How do we build shared collective memories? How does memory shape history? This volume presents a special perspective, emphasizing the role of memory processes in the construction of self-identity, of shared cultural norms and concepts, and of historical awareness. Although the results are fairly new and the techniques suitably modern, the vision itself is of course related to the work of such precursors as Frederic Bartlett and Aleksandr Luria, who in very different ways represent the starting point of a serious psychology of human culture. Pascal Boyer is Henry Luce Professor of Individual and Collective Memory, departments of psychology and anthropology, at Washington University in St. Louis. He studied philosophy and anthropology at the universities of Paris and Cambridge, where he did his graduate work with Professor Jack Goody, on memory constraints on the transmission of oral literature. He has done anthro- pological fieldwork in Cameroon on the transmission of the Fang oral epics and on Fang traditional religion. Since then, he has worked mostly on the experi- mental study of cognitive capacities underlying cultural transmission. After teaching in Cambridge, San Diego, Lyon, and Santa Barbara, Boyer moved to his present position at the departments of anthropology and psychology at Washington University, St. Louis. James V.