ED388177.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tourism Australia Update

Having trouble reading? version 29 July 2020 TOURISM AUSTRALIA UPDATE The tourism industry has had another tough week with interstate travel restrictions tightening and ongoing uncertainty around when the industry will see some return to normality. As frustrating as this is, we are also getting encouraging feedback about significant levels of pent up demand for domestic holidays – and a desire to have different types of holidays. So, while we continue to face some challenges, we can be confident, that when people are able to travel freely again, they will. Tourism Australia is continuing to develop its domestic campaign plans, more details of which we will be sharing this Friday 31 July at 11am in our next webinar. The webinar will include a consumer insights update from our Executive General Manager of Strategy & Research, Rob Dougan, and a marketing update from our Chief Marketing Officer, Susan Coghill. We will also be joined by Australia’s Tourism Minister, Simon Birmingham, who will give an update on Australia’s ongoing response to coronavirus. Register here. Also a reminder that over the past few weeks, Tourism Australia’s international teams have hosted a series of virtual market specific updates and you can watch recordings here. Phillipa Harrison LET YOUR CUSTOMERS KNOW YOUR BUSINESS IS COVID-SAFE While some tourism businesses are reopening across Australia and others continue to navigate tightening restrictions, implementing and communicating COVID-Safe measures to customers has never been more important. See some of the different approaches that businesses are taking here: Capricorn Enterprise Ovolo Hotels Questacon Perisher Mogo Zoo TOURISM AUSTRALIA ACTIVITY Australia included in Travel + Applications closing - Australia Leisure's World's Best Awards Marketplace Online Readers of Travel + Leisure have Applications for Australia ranked Tasmania and the Great Marketplace North America and Barrier Reef islands in the top 25 Australia Marketplace UK & World’s Best Islands category in Europe will close this Friday 31 the 2020 World's Best Awards. -

Ngaanyatjarra Central Ranges Indigenous Protected Area

PLAN OF MANAGEMENT for the NGAANYATJARRA LANDS INDIGENOUS PROTECTED AREA Ngaanyatjarra Council Land Management Unit August 2002 PLAN OF MANAGEMENT for the Ngaanyatjarra Lands Indigenous Protected Area Prepared by: Keith Noble People & Ecology on behalf of the: Ngaanyatjarra Land Management Unit August 2002 i Table of Contents Notes on Yarnangu Orthography .................................................................................................................................. iv Acknowledgements........................................................................................................................................................ v Cover photos .................................................................................................................................................................. v Abbreviations ................................................................................................................................................................. v Summary.................................................................................................................................................................................... 1 1 Introduction ....................................................................................................................................................................... 2 1.1 Background ............................................................................................................................................................... -

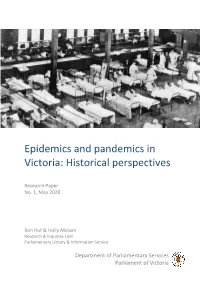

Epidemics and Pandemics in Victoria: Historical Perspectives

Epidemics and pandemics in Victoria: Historical perspectives Research Paper No. 1, May 2020 Ben Huf & Holly Mclean Research & Inquiries Unit Parliamentary Library & Information Service Department of Parliamentary Services Parliament of Victoria Acknowledgments The authors would like to thank Annie Wright, Caley Otter, Debra Reeves, Michael Mamouney, Terry Aquino and Sandra Beks for their help in the preparation of this paper. Cover image: Hospital Beds in Great Hall During Influenza Pandemic, Melbourne Exhibition Building, Carlton, Victoria, circa 1919, unknown photographer; Source: Museums Victoria. ISSN 2204-4752 (Print) 2204-4760 (Online) Research Paper: No. 1, May 2020 © 2020 Parliamentary Library & Information Service, Parliament of Victoria Research Papers produced by the Parliamentary Library & Information Service, Department of Parliamentary Services, Parliament of Victoria are released under a Creative Commons 3.0 Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivs licence. By using this Creative Commons licence, you are free to share - to copy, distribute and transmit the work under the following conditions: . Attribution - You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author or licensor (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Non-Commercial - You may not use this work for commercial purposes without our permission. No Derivative Works - You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work without our permission. The Creative Commons licence only applies to publications produced by the -

Commercially Harvested Macropods 2018-22

Commercially Harvested Macropods 2018–22 Prepared by: Industry and Development Assessment, Department of Environment and Heritage Protection © The State of Queensland (Department of Environment and Heritage Protection) 2017 Disclaimer This document has been prepared with all due diligence and care, based on the best available information at the time of publication. The department holds no responsibility for any errors or omissions within this document. Any decisions made by other parties based on this document are solely the responsibility of those parties. Information contained in this document is from a number of sources and, as such, does not necessarily represent government or departmental policy. If you need to access this document in a language other than English, please call the Translating and Interpreting Service (TIS National) on 131 450 and ask them to telephone Library Services on +61 7 3224 8412. This publication can be made available in an alternative format (e.g. large print or audiotape) on request for people with vision impairment; phone +61 7 3224 8412 or email <[email protected]>. March 2017 Definitions Carcase—the body of an animal slaughtered for meat, after removal of the offal. Note: from the Macquarie Dictionary. Dealer site—licensed site that enables the purchase of harvested macropods from a licensed harvester but does not allow the processing of the harvested macropod. Ecologically sustainable development—this plan employs the definition contained in the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999. In general this definition includes the precautionary principle, inter- generational equity, conservation of biological diversity and ecological integrity, and improved valuation of environmental factors. -

Federal Political Update

CCH Parliament Western Australian Political Update Issue: 6 of 2012 Date: 6 February 2012 For all CCH Parliament enquiries, contact: CCH Parliament Phone 02 6273 2070 Fax 02 6273 1129 A brand of CCH Australia, a Wolters Kluwer business. PO Box 4746 KINGSTON ACT 2604 Timely, Accurate, Relevant... CCH, The Professional's First Choice ISSN: 1442-7990 Western Australian Political Update A weekly summary report of political, government and legislative news Portfolio Index – please select: Aboriginal Affairs............................................................................................................................... 3 Education .......................................................................................................................................... 4 Energy............................................................................................................................................... 5 Environment...................................................................................................................................... 5 Food Industry .................................................................................................................................... 6 Foreign Affairs................................................................................................................................... 6 Health................................................................................................................................................ 6 Housing & Property.......................................................................................................................... -

The Importance of Boundaries

The importance of boundaries Colin Hughes Emeritus Professor of Politic Science, University of Queensland Research Paper 1 (November 2007) Democratic Audit of Australia Australian National University Canberra, ACT 0200 Australia http://democratic.audit.anu.edu.au The views expressed are the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Democratic Audit of Australia. If elections are to be thought fair, their outcomes should correspond as closely as possible to the inputs of voter preferences. A particular percentage of the votes counted for a party should produce close to the same percentage of the seats won by that party. Down that path lie the topics of partisan bias and proportional representation with multi-member electoral districts as the most common solution. But there is a second criterion of fairness which is that outcomes should correspond to the numbers of electors or people to be represented. That criterion is often called equality, and down that path lie the topics of malapportionment and enforced equality as a solution. The two criteria may not work in the same direction.1 In Australia the problem of equality has been debated mainly with respect to the dichotomy of town and country, ‘town’ usually meaning the State capital(s) which have been invariably by far the largest urban center in each State and ‘country’ the rest, though sometimes the larger provincial cities and towns get lumped in with their local metropolis. Should town voters have the same quantity of representation, measured by the number of electors in the electoral districts, as country voters? There has also been a sub-plot, which is what this paper is about, that concerns the existence of a small number of electoral districts spread over exceptionally large areas in which the population, and consequently the numbers of electors, is relatively thin on the ground and widely scattered. -

Management Plan for the Commercial Harvest of Kangaroos in Western

Management Plan for the Commercial Harvest of Kangaroos in Western Australia 2014–2018 Effective for the period: 1 April 2014 – 31 December 2018 Management Plan for the Commercial Harvest of Kangaroos in WA 2014–2018 i Published by: Department of Parks and Wildlife Locked Bag 104 BENTLEY DELIVERY CENTRE WA 6983 Phone: (08) 9219 9000 Fax: (08) 9334 0498 email: [email protected] Web : www.dpaw.wa.gov.au September 2013 Cover photo: Babs and Bert Wells/DPaW Management Plan for the Commercial Harvest of Kangaroos in WA 2014–2018 ii CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................... 1 2. LEGISLATIVE FRAMEWORK ............................................................................... 2 2.1 Commonwealth ............................................................................................ 2 2.2 Western Australia ......................................................................................... 3 3. BIOLOGY, ECOLOGY AND CONSERVATION OF KANGAROOS .................... 10 3.1 Introduction ................................................................................................. 10 3.2 Biology and Ecology ................................................................................... 10 3.3 Conservation Status ................................................................................... 16 3.4 Threats, Issues and Assessment of Impacts .............................................. 16 4. GOALS AND AIMS ............................................................................................. -

National Native Title Tribunal

NATIONAL NATIVE TITLE TRIBUNAL ANNUAL REPORT 1996/97 ANNUAL REPORT 1996/97 CONTENTS Letter to Attorney-General 1 Table of contents 3 Introduction – President’s Report 5 Tribunal values, mission, vision 9 Corporate overview – Registrar’s Report 10 Corporate goals Goal One: Increase community and stakeholder knowledge of the Tribunal and its processes. 19 Goal Two: Promote effective participation by parties involved in native title applications. 25 Goal Three: Promote practical and innovative resolution of native title applications. 30 Goal Four: Achieve recognition as an organisation that is committed to addressing the cultural and customary concerns of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. 44 Goal Five: Manage the Tribunal’s human, financial, physical and information resources efficiently and effectively. 47 Goal Six: Manage the process for authorising future acts effectively. 53 Regional Overviews 59 Appendices Appendix I: Corporate Directory 82 Appendix II: Other Relevant Legislation 84 Appendix III: Publications and Papers 85 Appendix IV: Staffing 89 Appendix V: Consultants 91 Appendix VI: Freedom of Information 92 Appendix VII: Internal and External Scrutiny, Social Justice and Equity 94 Appendix VIII: Audit Report & Notes to the Financial Statements 97 Appendix IX: Glossary 119 Appendix X: Compliance index 123 Index 124 National Native Title Tribunal 3 ANNUAL REPORT 1996/97 © Commonwealth of Australia 1997 ISSN 1324-9991 This work is copyright. It may be reproduced in whole or in part for study or training purposes if an acknowledgment of the source is included. Such use must not be for the purposes of sale or commercial exploitation. Subject to the Copyright Act, reproduction, storage in a retrieval system or transmission in any form by any means of any part of the work other than for the purposes above is not permitted without written permission. -

DEW Annual Report 2017-18

Department for Environment and Water 2017-18 Annual Report Department for Environment and Water 81-95 Waymouth Street, Adelaide SA 5000 GPO Box 1047, Adelaide SA 5001 www.environment.sa.gov.au Contact phone number +61 8 8204 1910 Contact email [email protected] ISSN 2202-6673 Date presented to Minister: 28 September 2018 Public – I2 – A1 2017-18 ANNUAL REPORT for the DEPARTMENT FOR ENVIRONMENT AND WATER Contents Contents .................................................................................................................... 3 Section A: Reporting required under the Public Sector Act 2009, the Public Sector Regulations 2010 and the Public Finance and Audit Act 1987 ................. 4 Agency purpose or role ..................................................................................................... 4 Objectives ......................................................................................................................... 4 Key strategies and their relationship to SA Government objectives ................................... 4 Agency programs and initiatives and their effectiveness and efficiency ............................. 6 Legislation administered by the agency ........................................................................... 27 Organisation of the agency .............................................................................................. 28 Other agencies related to this agency (within the Minister’s area/s of responsibility) ....... 28 Employment opportunity programs -

13 November 1985 COUNCIL 875

j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j VICTORIA PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) FORTY-NINTH PARLIAMENT SPRING SESSION 1985 Legislative Council VOL. CCCLXXX [From October 30,1985, to November 28, 1985} MELBOURNE: F. D. ATKINSON, GOVERNMENT PRINTER j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j The Governor *His Excellency Rear-Admiral SIR BRIAN STEWART MURRAY, KCMG, AO The Lieutenant-Governor The Honourable SIR JOHN McINTOSH YOUNG, KCMG The Ministry Premier The Hon. John Cain, MP Deputy Premier, and Minister for The Hon. R. C. Fordham, MP Industry, Technology and Resources Minister for Agriculture and Rural The Hon. E. H. Walker, MLC Affairs, and Minister for Planning and Environment Minister for Health The Hon. D. R. White, MLC Minister for Education The Hon. I. R. Cathie, MP Minister for Employment and Industrial The Hon. S. M. Crabb, MP Affairs . Minister for Community Services The Hon. C. J. Hogg, MLC Treasurer The Hon. R. A. Jolly, MP Attorney-General .. The Hon. J. H. Kennan, MLC Minister for Conservation, Forests and The Hon. -

New Online Pre-Approval Process for Travel Into South Australia From

Tuesday 30 June 2020 16:57 pm New online pre-approval process for travel into South Australia From tomorrow 1 July 2020, a new online cross-border travel process will be in place for travellers entering South Australia from interstate. While border restrictions have been eased for people entering South Australia directly from Queensland, Western Australia, Tasmania and Northern Territory, all workers inbound to South Australia (including workers returning from rosters interstate) should complete an online form that will be available from midnight tonight at this web page. Travellers are required to complete an online questionnaire and upload the supporting letter previously used to enable border crossings. The traveller will then receive an email containing a unique code that will have to be shown at the border to ensure entry into South Australia. Importantly, there are no other changes to the Cross Border Travel Direction. While there will be an adjustment period in the transition to the new system this week, SA Police are committed to ensuring this roll-out does not adversely impact on existing essential worker movements for industry. Any issues will be managed pragmatically as they have been to date. Cross-border movements by workers should continue as planned – those moving tonight and early tomorrow will simply need to complete the process on arrival, with all others subsequently crossing the border required to complete the online process as soon as it is available. Once fully operational, this process will streamline the cross-border process and provide further operating certainty to all companies working across borders. Voluntary asymptomatic testing Given concern about community transmission of Covid-19 in Victoria, SA Pathology has seen an increase in contact from companies regarding the opportunity to have inbound workers tested, particularly those arriving from Victoria, in order to mitigate risk to their operations and reputation. -

Retrieving Woomera's Heritage: Recovering Lost Examples of the Material Culture of Australian Space Activities

Kerrie Dougherty Retrieving Woomera's heritage: recovering lost examples of the material culture of Australian space activities Introduction Woomera Rocket Range. Once it was a name to conjure with, carrying all the mystique of Cold War secrecy coupled with the excitement of space exploration. Yet today, the site where Australia joined the 'space club', where both Britain and Europe made their first attempts at developing an independent launch capability, is largely abandoned and virtually forgotten by younger generations ofAustralians, who associate Woomera only with a controversial US military tracking stationI and, most recently, an equally controversial detention centre for illegal immigrants.2 Established in 1947 as the long-range weapons test facility of the Anglo-Australian Joint Project, Woomera was born out of Britain's Cold War desire to develop its own missile systems and nuclear deterrent. Unable to test such weapons adequately within the narrow confines of the United Kingdom and its surrounding waters, Britain sought a secure test range within the Commonwealth and ultimately selected a location in the remote outback of South Australia which offered huge tracts of virtually uninhabited desert over which to fly missiles, drop bombs and, later (though this was not immediately in the minds of the initial developers), launch rockets into space. Woomera, at its greatest extent, was the largest overland weapons test range in the Western world, and - at one point - the busiest. Over the lifetime of the Joint Project (1947-80)3 more than 4000 British, European, American and Australian missiles and rockets and 3000 bombs and other weapons4 were launched and tested there, for both military and civilian purposes (Figure 1).