Nutrition; *Planning; Tab' 7Ta); *Technological Adtancement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

OPERATION MANUAL ® BROASTER 1600 and 1800 PRESSURE FRYER W/SMART TOUCH CONTROL

OPERATION MANUAL ® BROASTER 1600 AND 1800 PRESSURE FRYER w/SMART TOUCH CONTROL Be sure ALL installers read, understand, and have access to this manual at all times. 1600 1800 Genuine Broaster Chicken®, Broasted®, Broaster Chicken®, Broaster Foods®. and Broasterie® are registered trademarks. Usage is available only to licensed operators with written authorization from The Broaster Company. Broaster Company 2855 Cranston Road, Beloit, WI 53511-3991 608/365-0193 broaster.com Design Certified By: 1600: CSA, NSF and UL © 2014 The Broaster Company 1800: CSA (AGA & CGA), NSF and UL Manual #17269 8/13 Rev 12/14 Printed in U.S.A. FOR YOUR SAFETY Do not use or store gasoline or other flammable vapors or liquids in the vicinity of this or any other appliance. Improper installation, adjustments, alteration, service or maintenance can cause property damage, injury or death. Read the installation, operating and maintenance instructions thoroughly before installing or servicing this equipment. For the sake of safety and clarity, the following words used in this manual are defined as follows: Indicates an imminently hazardous situation which, if not avoided, could result in serious injury or death. Indicates a potentially hazardous situation which, if not avoided, could result in serious injury or death. Indicates a potentially hazardous situation which, if not avoided, could result in minor injury, property damage or both. All adjustments and repairs shall be made If at any time the controller by an authorized Broaster Company repre- stays on when the power sentative. switch is moved to the OFF position, dis- connect the power to the unit and contact If there is a power failure, turn cook/filter your local Broaster Company representative switch OFF. -

View Newsletter

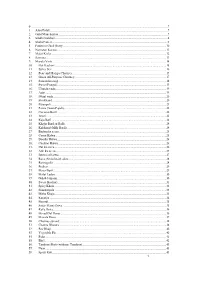

0. ..........................................................................................................................................................................................7 1. Aloo Palak.................................................................................................................................................................7 2. Gobi Manchurian.....................................................................................................................................................7 3. Sindhi Saibhaji..........................................................................................................................................................8 4. Shahi Paneer .............................................................................................................................................................9 5. Potato in Curd Gravy.............................................................................................................................................10 6. Navratan Korma .....................................................................................................................................................11 7. Malai Kofta.............................................................................................................................................................12 8. Samosa.....................................................................................................................................................................13 -

OK Industries

+91-8048761961 OK Industries https://www.indiamart.com/okinds/ We are one of the leading Manufacturer and Exporter of Non Stick Cookware, Stainless Steel Pressure Cooker, Hard Anodised Cookware. An ISO - 9001:2008 certified company, OK Industries has grown consistently over the last 59 years. About Us Established in 1956 by Shri Om Prakash Kapur, OK Industries is a leading Manufacturer and Exporter of Non Stick Cookware, Stainless Steel Pressure Cooker, Hard Anodised Cookware, Non Stick Gift Sets, Marble Coated Cookware, Stainless Steel Gift Set, Vacuum Bottle in the country. OK Industries is an ISO - 9001:2000 certified company and has grown consistently over the last 65 years. The company is also one of the few authorized licensee of the prestigious Teflon Coating by Du Pont Co. of USA. As of now, OK Industries offer a large variety of non-stick cookware, hard anodized cookware. Quality is of utmost importance to us and thus our products go through a series of stringent quality checks before they are ready to be used by the consumer. Our non-stick cookware bear ISI mark IS: 1660 Part-I and are manufactured from virgin aluminium metal. Our high quality products have been certified by the Bureau of Indian Standards. The company is equipped with latest machinery for production and quality control. We as a company encourage our distributors and dealers to perform better by offering them with attractive incentives. Getting repeat orders from overseas buyers has become a trend. For more information, please visit https://www.indiamart.com/okinds/profile.html -

Download a 27-Page PDF of the 2016

1966 • NRN celebrates 50 years of industry leadership • 2016 WWW.NRN.COM APRIL 4, 2016 CONSUMER PICKS THE DEFINITIVE ANNUAL RANKING OF TOP RESTAURANT BRANDS, PAGE 10 TM ove. It isn’t a word often used in businesses, but it is a word often used about businesses. Whether a customer loves your brand, loves your menu, loves your servers or loves your culture translates into whether your business will thrive. Love is a word businesses should get comfortable with. The annual Consumer Picks special report from Nation’s Restau- rant News and WD Partners is a measure of restaurant brand success from the eyes of their guests. Surveying customers to the tune of 37,339 ratings, Lincluding specific data points on 10 restaurant brand attributes like Cleanliness, Value, Service and Craveability, Consumer Picks ranks 173 chains on whether or not their guests are feeling the love. In this year’s report, starting on page 10, there is valuable analysis on top strat- egies to win over the customer, from the simplicity of cleaning the restaurant to the more complex undertaking of introducing an app to provide guests access to quick mobile payment options. Some winning brands relaunched menus and oth- ers redesigned restaurants. It is very clear through this report’s data and operator insights that to satisfy today’s demanding consumer, a holistic approach to your brand — who you are, what you stand for, the menu items you serve, the style in which you serve it and the atmosphere you provide to your guest — is required. This isn’t anything new. -

I UG Food Preservation

Dr Ambedkar Government Arts College , Vyasarpadi, Chennai - 39 I B.Sc - Home Science - Nutrition , Food Service Management and Dietetics (UG) 2020-2021 Major paper FOOD PRESERVATION AND PROCESSING Unit - I Nature of harvested crop • The quality of harvested crop is dependant on the conditions of growth and on post harvest treatment. Storage condition of a crop is dependent on the function of composition, resistance to attacks by microorganisms, external conditions of temperature and gases in the environment • The most important characteristic of freshly harvested fruits and vegetables is that they are alive and respiring. • Ripening rendering the produce edible; as indicated by by taste. During ripening, starch is converted to sugar. When respiration declines, senescence (it ends at the death of the tissue of the fruit) develops in the last stage. • Maturity is indicated by skin colour, optical methods, shape, size, aroma, fruit opening, leaf changes and firmness. • Low temperature also disrupt the complex sequence of biochemical reactions taking place in plant tissue and cause a disorder known as chilling injury. • After harvesting decline in the rate of oxygen uptake and Carbon dioxide evolution to a low value is followed by a shark rise to a peak, terminating in pest- climacteric stage. The peak to minimum ratio tends to increase with temperature. this ratio varies among fruits. the slope of the rise varies with species maturity, temperature and the oxygen and Carbon dioxide of the storage chamber. Plant product storage Fresh fruits and vegetable maintain life processes during storage. As long as they are alive, they are able to resist the growth of spoilage organisms to some degree. -

To Travel the World For

SAVORED JOURNEYS PRESENTS 101 DISHES TO TRAVEL THE WORLD FOR EXPLORE THE CULTURE THROUGH THE FOOD savoredjourneys.com THE ULTIMATE LIST OF FOOD TO TRAVEL FOR By Laura Lynch of Savored Journeys Thank you for downloading 101 Dishes to Travel the World For and signing up to receive updates from Savored Journeys. I strongly believe there's no better way to discover a new culture than through food. That's why I put together this guide - so you can see for yourself all the amazing foods in the world that are absolutely worth traveling for! If you love food as much as we do, then you've come to the right place, because that's what Savored Journeys is all about. In the near future, we will be releasing an Around the World cookbook with all our favorite International recipes you can cook at home, along with wine pairings. In the meantime, we hope to pique your curiosity, perhaps encourage a bit of drooling and, above all, inspire you to travel for food. Visit us at http://www.savoredjourneys.com for more food and travel inspiration. WE ' RE GLAD YOU JOINED US! ABOUT SAVORED JOURNEYS From the tapas of Spain to the curries of Thailand, there's no food we're not willing to try, even if it involves intestines or insects. No matter where our adventures take us, food is a central part of our trip. Since eating involves all 5 senses, you’re in a heightened state when you interact with food, so intentionally experiencing food while you’re traveling will increased the intensity of the memories you build. -

Grocers and Service Station Dealers Ask Congress to Sponsor Credit Card Fair Fee Act

Grocers and service station dealers ask Congress to sponsor Credit Card Fair Fee Act On April 9, a national contingent seat at the negotiating table when of retail grocers and service station fees are determined, an opportunity dealers - including AFPD staff retailers are currently denied. and board members - traveled to AFPD represented your interests Washington D.C. in a national as staff and board met with your lobbying effort to ask their members members of Congress during “A of Congress to co-sponsor and vote Day in Washington Dedicated to for H.R. 5546. the Credit Card the Credit Card Fair Fee Act.” All AFPD Foundation Fair Fee Act. Sponsored by House attendees at the event, which was Golf Outing Judiciary Committee Chairman coordinated by the National Grocers John Conyers (D-MI) and 14 Association and Food Marketing affecting retailers’ bottom line,” coming soon! co-sponsors, the bill is designed Institute, were enthusiastic about says Jane Shallal, AFPD president. to counter the market power of the positive responses they received “We must work collectively and be It's time to register for the premier Visa and MasterCard in setting from Congressional representatives persistent to stop this practice and golf event of the season - the AFPD credit card interchange fees. H R. and senators. restore transparency to the credit Foundation Golf Outing! This year it is 5546 will open up the market to “Credit card fees are eating away card industry,” she added. scheduled for July 16 at the beautiful competition within the credit card at the profit of our members and To see how credit card fees affect Fox Hills in Plymouth, Mich. -

A Taste of Macedonia

A Taste of Macedonia Traditional Macedonian Recipes Macedonian Australian Welfare Association of Sydney Inc. Acknowledgments Macedonian Australian Welfare Association of Sydney Inc. (MAWA) would like to acknowledge the Macedonia FAQ (frequently asked questions) website where these recipes were compiled. MAWA would also like to thank and acknowledge “Multicultural Recipes for Every Day” published by St. George (Multicultural Day Care Program) Migrant Resource Centre. Aim Now in its second printing this Macedonian recipe book has been complied with a view to providing culturally appropriate menu options to aged care services. It was been published in the hopes that the cultural identify of Macedonian people in residential aged care and aged care services in the Sydney area is maintained and encouraged. Table of Contents Appetizers, Bread and Salad Ajvar (Relish Dip) ……………………………….………………………………… 6 Leb (Bread) …………………………………………………………………………. 7 Turshija (Jernikitz Peppers) …………………………………………………… 8 Shopska Salata (Shopska Salad) ……….…………………………………… 9 Tarator (Cucumber Yoghurt Salad) ……………………………………….. 10 Turkish Coffee (Macedonian Espresso) ……………….………………….. 11 Main Courses Tava so Oriz (Macedonian Chicken Stew) …….….……………………… 13 Kjebapchinja (Macedonian Sausages) ……………………………………… 14 Kjoftinja (Meatballs) …………………………………………………………….. 15 Musaka ………………………………………………………………………………. 16 Muchkalica from Shar Planina ……………………………………………….. 17 Pastrmajlija (Macedonian Pizza) ……………………………………………. 18 Pecheno Jagne so Zelka (Steamed Lamb with Cabbage) …………. 19 Polneti Piperki -

Food Management and Child Care Theory

FOOD MANAGEMENT AND CHILD CARE THEORY VOCATIONAL EDUCATION HIGHER SECONDARY - FIRST YEAR A Publication under Government of Tamilnadu Distribution of Free Textbook Programme (NOT FOR SALE) Untouchability is a sin Untouchability is a crime Untouchability is inhuman TAMILNADU TEXTBOOK CORPORATION College Road, Chennai - 600 006. PDF created with pdfFactory Pro trial version www.pdffactory.com © Government of Tamilnadu First Edition - 2010 Chairperson Dr. U.K. Lakshmi, Professor, Department of Food Science and Nutrition, Avinashilingam University for Women, Coimbatore - 641 043. Authors and Reviewers Dr. V. Saradha Ramadas, Professor, Department of Food Service Management and Dietetics Avinashilingam University for Women, Coimbatore - 641 043. Mrs. C. Geetha, Vocational Teacher, C.C.M.A. Govt. Girls Higher Secondary School, Raja Street, Coimbatore - 641 001. Mrs. K. Raheema Begum, PG Teacher (Home Science), Jaivabai Corporation Girls Higher Secondary School, Tirupur - 641 601. This book has been prepared by The Directorate of School Education on behalf of the Government of Tamilnadu This book has been printed on 60 G.S.M. Paper PDF created with pdfFactory Pro trial version www.pdffactory.com CONTENTS Page 1. FOOD 1.1 Basics of Food 1 1.2 Definitions 3 1.3 Classification of Food Groups 7 1.4. Recommended Dietary Allowances (RDA) 10 1.5. Food preparation 16 1.6. Fast Foods 27 2. NUTRITION 2.1. Energy 31 2.2. Carbohydrates, Proteins and Fats 33 2.3. Vitamins 37 2.4. Minerals 42 2.5. Water 46 3. NUTRITIONAL STATUS AND THERAPEUTIC DIETS 3.1. Nutritional Status 52 3.2. Routine Hospital Diets 56 3.3. Special Feeding Methods 60 4. -

Download the Program Brochure

An American favorite for generations, Genuine Broaster Chicken® is simply the very best-tasting chicken you can find. Chicken lovers across America, and worldwide, tell us so. When you become an official licensed trademark operator, you’ll have everything you need to serve your guests the amazing tastes they’ll be back for again and again. Business is better Broasted! Chicken Perfected Together Chicken Perfected Together. For over 65 years, Genuine Broaster Chicken® has delivered chicken that customers crave. Millions of people love fried chicken, and the chicken they prefer is Genuine Broaster Chicken. Our chicken is hand breaded and Broasted® using our proprietary recipe and process, and served fresh daily. Business is Better Broasted. As a licensed trademark operator, you’ll get the products, equipment and support you need to serve your customers a uniquely delicious and satisfying guest favorite. Thousands of satisfied foodservice operators across the country and around the world already do. Preparing Genuine Broaster Chicken begins with our time proven recipe. We add our unique marinade and coating to our proprietary Broaster® Pressure Fryer cooking process, and you can offer products with the irresistible flavor, crispiness and juiciness that attracts more customers – and helps your profits soar. And with no franchise or licensing fees, you keep the profits you earn. Genuine Broaster Chicken® Spicy - Perfectly spiced for every bite. Because it’s pressure fried, Genuine Broaster Chicken® is more tender, juicier and flat out tastes better than ordinary fried chicken – even better than other pressure fried chicken for that matter! With more than 65 years of experience, no one understands your needs better than the Broaster® Company. -

Kitchen Curiosities KITCHEN CURIOSITIES 2

1 Authors: Anna Gunnarsson and Jenny Schlüpmann Kitchen Curiosities KITCHEN CURIOSITIES 2 Conceptual introduction The teaching unit ‘Kitchen Curiosities’ plays in two different settings: the school yard (→ page 38) and the kitchen itself (→ page 43). If you want to know what can be found in a kitchen you can head for the vocabulary corner. [1] In the story, the children are introduced to the origin of the Hindu-Arabic numeral system. The Hindu-Arabic numerals are compared to Roman and ancient Egyptian numerals. The children also learn about different kinds of bread and baked goods: 5 chapatis from India, Afghanistan and East Africa 5 naan taftoon from Iran, Pakistan and Northern India 5 pita bread from Syria, Lebanon and Greece 5 focaccia from Italy 5 scones from Great Britain Except for the chapati dough, all these doughs contain yeast or baking powder: dry yeast in naan taftoon and pita bread, fresh yeast in focaccia and baking powder in scones. The children are asked to decipher bread recipes in Arabic, Hindi and Persian. This puts children from countries with Latin writing in a situation in which they are confronted with a text they cannot read – a common situation for children who are not yet familiar with Latin writing. The kitchen is a perfect place to experiment with yeast and dough. In the first experiment (→ page 48), the children investigate the effects of dry yeast and learn how to handle experi- ments with several independent parameters. The second experiment (→ page 50) is about how the different doughs float or sink. In the third experiment (→ page 52), cabbage juice, lemon juice and baking soda are used to change the colour of the dough. -

Dutch Pot Continue to Be a Popular in Jamaican Coal Stove Households

© Copyright by Jamaica Information Service 2014 Jamaica’s Culinary Roots Jamaican cuisine is a combination of locally grown and imported ingredients, spices and flavours as well as cooking techniques that are influenced by the major ethnic groups: Tainos, Africans, Europe- ans, Chinese and Indians. Although there are mod- ern pieces of equipment used in food preparation in kitchens islandwide, there are long-established processes and tools that are indigenous and tradi- tional, which have been used in creating delicious meals for generations. Some utensils such as the Dutch Pot continue to be a popular in Jamaican Coal Stove households. Others such as the yabba are waning The coal stove is a small charcoal fuelled cooker in popularity and are considered to be heirlooms with a basin-like top covered by a flat metal grill rather than cooking tools. Identified here are some attached to a long hollowed cylindrical foot. Similar of the traditional cooking tools and methods, their to a single cooktop, the coal stove was used to places of origin of and the materials used to make cook a wide range of foods. Meats could be placed these tools. directly on the grill of the coal stove or on sticks laid across the top of the stove to be grilled or smoked. Cooking Equipment Pots that were usually round and blackened were positioned on coals for cooking. The coal stove is Jamaican cooking amenities have evolved from still a primary cooking device for some Jamaican open wood fuelled fires to high-end modern gas families, especially when roasting breadfruit.