A City Within a City

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Contact Sheet

CONTACT SHEET The personal passions and public causes of Prince Albert, husband of Queen Victoria, are revealed, as photographs, prints and letters are published online today to mark the 200th anniversary of his birth After Roger Fenton, Prince Albert, May 1854, 1889 copy of the original Queen Victoria commissioned a set of private family photographs to be taken by Roger Fenton at Buckingham Palace in May 1854, including a portrait of Albert gazing purposefully at the camera, his legs crossed, in front of a temporary backdrop that had been created. Queen Victoria and Prince Albert In a letter beginning ‘My dearest cousin’, written in June 1837, Albert congratulates Victoria on becoming Queen of England, wishing her reign to be long, happy and glorious. Royal Archives / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2019 Queen Victoria kept volumes of reminiscences between 1840 and 1861. In these pages she describes how Prince Albert played with his young children, putting a napkin around their waist and swinging them backwards and forwards between his legs. The Queen also sketched the scenario (left) Royal Archives / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2019 Press Office, Royal Collection Trust, York House, St James’s Palace, London SW1A 1BQ T. +44 (0)20 7839 1377, [email protected], www.rct.uk After Franz Xaver Winterhalter, Bracelet with photographs of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert’s nine children, 1854–7 This bracelet was given to Queen Victoria by Prince Albert for her birthday on 24 May 1854. John Jabez Edwin Mayall, Frame with a photograph of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert, 1860 In John Jabez Edwin Mayall’s portrait of 1860, the Queen stands dutifully at her seated husband’s side, her head bowed. -

Design, Access, & Heritage Statement Royal Albert Hall: Busts 9435 / Rev

Design, Access, & Heritage Statement Royal Albert Hall: Busts 9435 / Rev A00 July 2021 Document Control Revision Description Originator Approved Date Application for Planning Permission & Listed A00 Feilden+Mawson LLP ALR 08/07/2021 Building Consent Feilden+Mawson LLP 21-27 Lambs Conduit Street London WC1N 3NL Tel: 020 7841 1980 www.feildenandmawson.com 2 of 28 Feilden+Mawson Royal Albert Hall: Busts | Rev A00 | July 2021 Contents 1.0 Introduction 4 2.0 Site Assessment & Context 5 2.1 Location & Legal Designations 5 2.2 Planning Policy 6 2.3 Historic Context 8 3.0 Proposals 10 3.1 The Brief 10 3.1 North Porch 12 3.2 South Porch 15 4.0 Heritage Impact Assessment 20 4.1 Significance Assessment 20 4.2 Impact of Proposals 20 Appendices A: Listing Description 22 B: Pre-Application Advice from WCC 23 C: London Stone Carving, Design Statement 24 D: Poppy Field, Design Statement 26 Feilden+Mawson Royal Albert Hall: Busts | Rev A00 | July 2021 3 of 28 1.0 INTRODUCTION This design, access & heritage statement sets out proposals for new busts to the empty external niches to the North and South Porches of the Royal Albert Hall to coincide with its 150th anniversary in 2021. The Hall was constructed in 1867-71 and designed by Lieutenant-Colonel Henry Scott. It is Grade I listed, designated in 1958 and forms part of the Knightsbridge Conservation Area. The new busts are proposed to be installed to the twin niches to the North and South Porches. To the North Porch stone busts of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert will face Kensington Gore and the Albert Memorial within Hyde Park, while to the south bronze busts of Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip will face the Queen Elizabeth II Steps leading down to Prince Consort Road. -

Architectural Tour of Exhibition Road and 'Albertopolis'

ARCHITECTURAL TOUR OF EXHIBITION ROAD AND ‘ALBERTOPOLIS’ The area around Exhibition Road and the Albert Hall in Kensington is dominated by some of London’s most striking 19th- and 20th-century public buildings. This short walking tour is intended as an introduction to them. Originally this was an area of fields and market gardens flanking Hyde Park. In 1851, however, the Great Exhibition took place in the Crystal Palace on the edge of the park. It was a phenomenal success and in the late 1850s Exhibition Road was created in commemoration of the event. Other international exhibitions took place in 1862 and 1886 and although almost all the exhibition buildings have now vanished, the institutions that replaced them remain. Queen Victoria’s husband, Prince Albert, had a vision of an area devoted to the arts and sciences. ‘Albertopolis’, as it was dubbed, is evident today in the unique collection of colleges and museums in South Kensington. Begin at Exhibition Road entrance of the V&A: Spiral Building, V&A, Daniel Libeskind, 1996- The tour begins at the Exhibition Road entrance to the V&A, dominated now by a screen erected by Aston Webb in 1909 to mask the original boiler house yard beyond. Note the damage to the stonework, caused by a bomb during the Second World War and left as a memorial. Turn right to walk north up Exhibition Road, 50 yards on your right is the: Henry Cole Wing, V&A, Henry Scott with Henry Cole and Richard Redgrave, 1868-73 Henry Cole was the first director of the South Kensington Museum (now the V&A). -

London Albertopolis

Albertopolis A free self-guided walk in South Kensington Explore London’s quarter for science, technology, culture and the arts .walktheworld.or www g.uk Find Explore Walk 2 Contents Introduction 4 Route overview 5 Practical information 6 Detailed maps 8 Directions 10 Further information 16 Credits 17 © The Royal Geographical Society with the Institute of British Geographers, London, 2012 Walk the World is part of Discovering Places, the London 2012 Cultural Olympiad campaign to inspire the UK to discover their local environment. Walk the World is delivered in partnership by the Royal Geographical Society (with IBG) with Discovering Places (The Heritage Alliance) and is principally funded by the National Lottery through the Olympic Lottery Distributor. The digital and print maps used for Walk the World are licensed to RGS-IBG from Ordnance Survey. 3 Albertopolis Explore London’s quarter for science, technology, culture and the arts Welcome to Walk the World! This walk in South Kensington is one of 20 in different parts of the UK. Each walk explores how the 206 participating nations in the London 2012 Olympic and Paralympic Games have been part of the UK’s history for many centuries. Along the routes you will discover evidence of how many Olympic and Paralympic countries that have shaped our towns and cities. Prince Albert and Sir Henry Cole had a vision: an area of London dedicated to education and culture. It became a reality 150 years ago in South Kensington, and became fondly known as ‘Albertopolis’ after its royal patron. Albertopolis is home to some of London’s most spectacular buildings, world class museums and premier educational institutions. -

Local Area Guide Contents

LOCAL AREA GUIDE CONTENTS Overview page 02 Location page 04 Indulge page 10 Drink page 16 Dine page 26 Café page 38 Culture page 46 Shop page 54 Relax page 64 Nature page 72 Educate page 80 01 LOCAL AREA GUIDE | CONTENTS IN LONDON’S ROYAL BOROUGH Royal Warwick Square will offer a magnificent collection of apartments and penthouses designed for the classical London lifestyle. With a superb position in the heart of the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea, it is close to the illustrious neighbourhoods of Holland Park, Knightsbridge and Chelsea. These are amongst the most sought after parts of the Capital, transcending fashion to always be considered prime residential areas. Some of the Capital’s most famous cultural attractions, restaurants and bars are close at hand, as well as an array of luxury shops, parks and concert halls. With many options a short stroll away, Kensington is a truly desirable address from which to discover the very best of what London has to offer. This local guide is merely an introduction to the prestigious Kensington area, where there is always something new and interesting waiting to be revealed amongst the historical greats and local institutions. 02 LOCAL AREA GUIDE | OVERVIEW 129 ad nville Ro Pento REGENT’S Ci PARK ty Euston Ro ad LISTINGS PERFECTLY Old Street 132 K in g ’ s C POSITIONED r Baker Street o oad 135 ss bone R R aryle o M a d DRINK CAFÉ RELAX M 01 Barts 53 Balans 96 Bulgari Hotel 88 o r o 02 Gaucho 54 Café De Fred 97 Cobella BRITISH g a Tottenham Court MUSEUM t 03 K Bar at The Kensington 55 Café -

Albert Hall Mansions, Kensington Gore, London, SW7

Albert Hall Mansions, Kensington Gore, London, SW7 With stunning views overlooking Hyde Park and the Albert Memorial is this bright and spacious four bedroom lateral apartment with exceptional room dimensions with high ceilings, as well as a large balcony directly overlooking Hyde Park and the Royal Albert Hall. Accommodation comprises of a large entrance hallway, two reception rooms, and master bedroom with ensuite bathroom in addition to three further bedrooms, shower room, cloakroom and a large separate kitchen/breakfast room. Albert Hall Mansions is located next to the Royal Albert Hall. Access gates to Kensington Gardens and Hyde Park are only a short distance from the building. The nearest tube stations are within one mile at Gloucester Road and South Kensington. LARGE ENTRANCE HALL : DOUBLE RECEPTION ROOM : 2ND RECEPTION ROOM : KITCHEN/BREAKFAST ROOM : MASTER BEDROOM WITH ENSUITE BATHROOM : 3 FURTHER BEDROOMS : SHOWER ROOM : CLOAKROOM : SPACIOUS TERRACE/BALCONY : LIFT : PORTER : EPC Asking Price £6,500,000 Albert Hall Mansions, Kensington Gore, London, SW7 SUBJECT TO CONTRACT TERMS: TENURE: Share Of Freehold LEASE: SERVICE CHARGE: Approx. per annum PRICE: £6,500,000 IMPORTANT NOTICE Wedgewood Estates hereby give notice to anyone reading these particulars that :- 1. These particulars are prepared for the guidance only of prospective purchasers. Descriptions of a property are inevitably subjective and the descriptions contained herein are used in good faith as an opinion and NOT as a statement of fact. 2. The photograph(s) depict only certain parts of the property. It should not be assumed that any content/furnishings/furniture, etc., photographed are included in the sale. -

Royal Albert Hall South-West Quadrant Kensington Gore SW2 7AP

Royal Albert Hall South-west Quadrant Kensington Gore SW2 7AP City of Westminster Archaeological Building Record September 2020 www.mola.org.uk © MOLA Mortimer Wheeler House, 46 Eagle Wharf Road, London N1 7ED tel 0207 410 2200 email: [email protected] Museum of London Archaeology is a company limited by guarantee Registered in England and Wales Company registration number 07751831 Charity registration number 1143574 Registered office Mortimer Wheeler House, 46 Eagle Wharf Road, London N1 7ED Historic Townscape Record © MOLA 2018 1 P:\WEST\1613\na\Field\SBR\Report\2020\Coversheet_ABR(1.0).docx Royal Albert Hall South-West Quadrant Kensington Gore London SW7 2AP Site Code ABL17 National Grid Reference 526573 179556 Planning reference no. 17/00010/ADFULL A Level 2-3 standing building survey Sign-off History: Issue No. Date: Prepared by: Checked/ Approved by: Reason for Issue: 1 24/11/2020 Anna Nicola Mike Smith First issue Head of Buildings (Project Manager) Archaeology and Paul McGarrity Project Officer © MOLA Mortimer Wheeler House, 46 Eagle Wharf Road, London N1 7ED tel 0207 410 2200 Unit 2, Chineham Point, Crockford Lane, Basingstoke, Hampshire, RG24 8NA, Tel: 01256 587320 Email [email protected] Summary This report presents the findings of a building survey undertaken by MOLA (Museum of London Archaeology) at the Royal Albert Hall, in the City of Westminster. The survey was commissioned by the Royal Albert Hall and was required to satisfy a condition of planning consent (planning reference no. 15/06079/FULL) prior to the construction of a two-storey basement beneath the south-west quadrant and associated external manifestations. -

Kensington.Pdf

02 // 03 Old meets new in one of central London’s most enchanting residential areas. 151-161KensingtonHighStreet.com 04 // 01 THE ULTIMATE IN GRACIOUS MODERN LIVING An elegant historic façade. An exceptional collection of 27 beautifully restored apartments, of classic contemporary design, set within an Edwardian terrace. Right at the heart of one of London’s most desirable residential districts, and moments from the city’s vibrant West End. 151-161KensingtonHighStreet.com 02 // 03 INTERIORS OF CONTEMPORARY LUXURY Living Room | Apartment 4.04 | Fourth Floor 151-161KensingtonHighStreet.com 04 // 05 Kensington Oxford Kensington Hyde Kensington St Paul’s Heron Tower Piccadilly Royal Albert The London Canary Big Buckingham Regent’s Park Palace BT Tower Street Palace Gardens Park High Street Cathedral Tower 42 Serpentine Circus Hall Shard Eye Wharf Ben Palace Museums Victoria & Albert Museum Natural History Museum Science Museum Royal Garden Hotel Barkers Arcade Kensington Roof Gardens High Street Kensington Station 151-161KensingtonHighStreet.com 06 // 07 KENSINGTON - A QUALITY ADDRESS A place of exquisite pleasures. Affluent yet approachable, exclusive but vibrant, leafy Kensington may be a lively shopping hub but it also has some of the capital’s most tranquil parkland. It’s where refined gourmet restaurants rub shoulders with hip bars, where you’re steps from the world’s finest museums as well as the retail mecca of Harrods. A few kilometres from Piccadilly Circus, but a world apart. 151-161KensingtonHighStreet.com 08 // 09 DYNAMIC, DARING AND ENDLESSLY FASCINATING The capital is a thrilling place, with an energy all its own. London’s streets offer all the wealth of experience that the world can afford. -

Albertopolis a Self Guided Walk Around South Kensington

Albertopolis A self guided walk around South Kensington Explore London’s quarter for the arts and sciences Discover why it was created and how it has developed See some of the capital’s most iconic buildings Uncover remarkable stories of artists, inventors, explorers and spies .discoveringbritain www .org ies of our land the stor scapes throug discovered h walks 2 Contents Introduction 4 Route overview 5 Practical information 6 Detailed route maps 8 Commentary 10 Further information 37 Credits 38 © The Royal Geographical Society with the Institute of British Geographers, London, 2013 Discovering Britain is a project of the Royal Geographical Society (with IBG) The digital and print maps used for Discovering Britain are licensed to the RGS-IBG from Ordnance Survey Cover image: Detail of the Royal Albert Hall © Rory Walsh 3 Albertopolis Explore London’s quarter for science, technology, culture and the arts Over 150 years ago the place now called South Kensington was a series of open fields and market gardens. That was until two men had a vision for creating a part of London dedicated to science, education and the arts. Fondly known as ‘Albertopolis’ after its royal patron, the area was designed to celebrate the achievements and grandeur of An aerial view of Albertopolis (June 2011) Victorian Britain. © Andreas Praefcke, Wikimedia Commons (CCL) Albertopolis is still thriving today as the home of many of London’s world-class museums, cultural institutes and scientific organisations. It also includes dozens of embassies, hosts hundreds of international students and welcomes thousands of visitors from around the world. Explore London’s quarter for the arts and sciences on foot and find out how it was created. -

Displaying Italian Sculpture

DISPLAYING ITALIAN SCULPTURE: EXPLORING HIERARCHIES AT THE SOUTH KENSINGTON MUSEUM 1852-62 TWO VOLUMES VOLUME I : TEXT CHARLOTTE KATHERINE DREW PH.D UNIVERSITY OF YORK HISTORY OF ART NOVEMBER 2014 ABSTRACT The South Kensington Museum’s early collections were conceived in the wake of the Great Exhibition and sought a similar juxtaposition of the fine and applied arts. Whilst there is an abundance of literature relating to the Great Exhibition and the V&A in terms of their connection to design history and arts education, the place of sculpture at these institutions has been almost entirely overlooked – a surprising fact when one considers how fundamental the medium is to these debates as a connection between the fine and applied arts and historical and contemporary production. To date, scholars have yet to acknowledge the importance of sculpture in this context or explore the significance of the Museum in challenging sculpture’s uncertain position in the post-Renaissance division between craft and fine art. By exploring the nature of the origins of the Italian sculpture collection at the South Kensington Museum, which began as a rapidly increasing collection of Medieval and Renaissance examples in the 1850s, we can gain a greater understanding of the Victorian attitude towards sculpture and its conceptual limitations. This thesis explores the acquisition, display and reception of the Italian sculpture collection at the early Museum and the interstitial position that the sculptural objects of the Italian collection occupied between the fine and decorative arts. In addition, it considers the conceptual understanding of sculpture as a contested and fluid generic category in the mid-Victorian period and beyond, as well as the importance of the Museum’s Italian sculpture collection to late nineteenth-century revisions of the Italian Renaissance. -

Hop-On Hop-Off Map

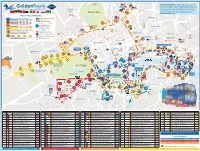

Events, Diversions and Disruptions: During the course of the year, many large events, such as the London Marathon and numerous other events and marches take place in Central London. These may require our routes to be diverted, and some of the stops may not be served. Our staff will be pleased to give you the information you require to ensure you can use our services with confidence. Routes and stops in the Docklands are liable to alterations and diversions as construction work on the ‘CrossRail’ project proceeds. Please note times may vary due to traffic congestion.Please check with Golden Tours staff if unsure. For the latest service information please visit www.hoponhopoffplus.com/service . Hop-on Hop-off Map Key Hop-on Hop-off – Blue Route & Stops Golden Tours Visitor Centres 1 A GTVC – Victoria 8 Hop-on Hop-off – Red Route & Stops B GTVC – Kensington C GTVC – Leicester Square 17 Hop-on Hop-off – Orange Route & Stops River Boat Ride Piers 1 London Eye Pier 61 Hop-on Hop-off – Collection & Drop Off Stops 2 Embankment Pier Hop-on Hop-off Plus – Interchange Bus Stops 3 Tower Pier 32 At stops common to multiple routes, Sightseeing Attractions buses run every 4 to 10 minutes London Underground Stations D National Rail Mainline Stations Diversion during the Crossrail construction works in the Paddington area Public Conveniences Stop No. Route Stop & Attractions First Bus Stop No. Route Stop & Attractions First Bus Stop No. Route Stop & Attractions First Bus Stop No. Route Stop & Attractions First Bus Stop No. Route Stop & Attractions First Bus 1 Victoria, Buckingham Palace Road, Stop 8 09.00 16 Park Lane, N/B, Tourist stop, Queen Elizabeth Gate 07.52 32 Westminster Bridge Road, Tourist stop, opp. -

Read the Home of Geography

The Home of Geography 51° 30’05”N;0°10’30”W • A history of Lowther Lodge by John Price Williams 2006 Professor Sir Gordon Conway 2003 Sir Neil Cossons 2000 Professor Sir Ron Cooke 1997 Lord Selborne 1993 Lord Jellicoe 1990 Sir Crispin Tickell 1987 Lord Chorley .” 1984 Sir George Bishop “I love this building. 1982 It is truly the home SirVivian Fuchs of geography 1980 Professor Michael Wise Michael Palin 1977 President, 2009-2012 Lord Hunt 1974 Sir Duncan Cumming 1971 Lord Shackleton 1969 Rear Admiral Sir Edmund Irving 1966 Sir Gilbert Laithwaite 1963 Professor L. Dudley Stamp 1961 Sir Raymond Priestley It is the home to the largest and most active scholarly geographical society in the world, supporting research, education, 1958 Lord Nathan 1954 expeditions and fieldwork, policy and General Sir James Marshall-Cornwall 1951 promoting public engagement. J.M. Wordie 1948 The Society’s House, as it’s often called, Sir Harry Lindsay 1945 Lord Rennell The home of geography welcomes some150,000 people a year to 1941 Sir George Clerk 1938 events and activities – and we are finding Sir Philip Chetwode 1936 new audiences all the time as we reach out Professor Henry Balfour 1933 Lowther Lodge has been the headquarters Sir Perry Cox to those with increasing curiosity about the 1930 of the Society for very nearly a century. Admiral SirWilliam Goodenough It’s one of the finestVictorian buildings in world and the way it works. 1 1927 The building has a fascinating history, Sir Charles Close 1925 Dr David Hogarth London, an iconic Grade II* listed building in 1922 which reflects the way the Society has Lord Ronaldshay a harmonious melange of three different eras 1919 developed and changed since moving into Sir Francis Younghusband 1917 – the grand1874 house looking out serenely Colonel SirThomas Holdich its home in1913.