Arxiv:Astro-Ph/0310879V1 30 Oct 2003 Srdee L 00.Scnayselrbr Ihnlresaebar Large-Scale Within Bars Stellar 1 Secondary About in 2000)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stark Broadening of Spectral Lines in Plasmas

atoms Stark Broadening of Spectral Lines in Plasmas Edited by Eugene Oks Printed Edition of the Special Issue Published in Atoms www.mdpi.com/journal/atoms Stark Broadening of Spectral Lines in Plasmas Stark Broadening of Spectral Lines in Plasmas Special Issue Editor Eugene Oks MDPI • Basel • Beijing • Wuhan • Barcelona • Belgrade Special Issue Editor Eugene Oks Auburn University USA Editorial Office MDPI St. Alban-Anlage 66 4052 Basel, Switzerland This is a reprint of articles from the Special Issue published online in the open access journal Atoms (ISSN 2218-2004) in 2018 (available at: https://www.mdpi.com/journal/atoms/special issues/ stark broadening plasmas) For citation purposes, cite each article independently as indicated on the article page online and as indicated below: LastName, A.A.; LastName, B.B.; LastName, C.C. Article Title. Journal Name Year, Article Number, Page Range. ISBN 978-3-03897-455-0 (Pbk) ISBN 978-3-03897-456-7 (PDF) Cover image courtesy of Eugene Oks. c 2018 by the authors. Articles in this book are Open Access and distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license, which allows users to download, copy and build upon published articles, as long as the author and publisher are properly credited, which ensures maximum dissemination and a wider impact of our publications. The book as a whole is distributed by MDPI under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons license CC BY-NC-ND. Contents About the Special Issue Editor ...................................... vii Preface to ”Stark Broadening of Spectral Lines in Plasmas” ..................... ix Eugene Oks Review of Recent Advances in the Analytical Theory of Stark Broadening of Hydrogenic Spectral Lines in Plasmas: Applications to Laboratory Discharges and Astrophysical Objects Reprinted from: Atoms 2018, 6, 50, doi:10.3390/atoms6030050 ................... -

A Basic Requirement for Studying the Heavens Is Determining Where In

Abasic requirement for studying the heavens is determining where in the sky things are. To specify sky positions, astronomers have developed several coordinate systems. Each uses a coordinate grid projected on to the celestial sphere, in analogy to the geographic coordinate system used on the surface of the Earth. The coordinate systems differ only in their choice of the fundamental plane, which divides the sky into two equal hemispheres along a great circle (the fundamental plane of the geographic system is the Earth's equator) . Each coordinate system is named for its choice of fundamental plane. The equatorial coordinate system is probably the most widely used celestial coordinate system. It is also the one most closely related to the geographic coordinate system, because they use the same fun damental plane and the same poles. The projection of the Earth's equator onto the celestial sphere is called the celestial equator. Similarly, projecting the geographic poles on to the celest ial sphere defines the north and south celestial poles. However, there is an important difference between the equatorial and geographic coordinate systems: the geographic system is fixed to the Earth; it rotates as the Earth does . The equatorial system is fixed to the stars, so it appears to rotate across the sky with the stars, but of course it's really the Earth rotating under the fixed sky. The latitudinal (latitude-like) angle of the equatorial system is called declination (Dec for short) . It measures the angle of an object above or below the celestial equator. The longitud inal angle is called the right ascension (RA for short). -

Readingsample

Stellar Physics 2: Stellar Evolution and Stability Bearbeitet von Gennady S. Bisnovatyi-Kogan, A.Y. Blinov, M. Romanova 1. Auflage 2011. Buch. xxii, 494 S. Hardcover ISBN 978 3 642 14733 3 Format (B x L): 15,5 x 23,5 cm Gewicht: 1024 g Weitere Fachgebiete > Physik, Astronomie > Astronomie: Allgemeines > Astrophysik Zu Inhaltsverzeichnis schnell und portofrei erhältlich bei Die Online-Fachbuchhandlung beck-shop.de ist spezialisiert auf Fachbücher, insbesondere Recht, Steuern und Wirtschaft. Im Sortiment finden Sie alle Medien (Bücher, Zeitschriften, CDs, eBooks, etc.) aller Verlage. Ergänzt wird das Programm durch Services wie Neuerscheinungsdienst oder Zusammenstellungen von Büchern zu Sonderpreisen. Der Shop führt mehr als 8 Millionen Produkte. Chapter 8 Pre-Main Sequence Evolution As can be seen from the calculations of cloud collapse described in Sect. 7.2,stars with mass M>3Mˇ appear in the optical range immediately near to the main se- quence. Objects of lower mass exist for part of the time as optical stars with radiation due to gravitational contraction energy. Consider evolution of a star from its ap- pearance in the optical region until it reaches the main sequence, and its central temperature becomes sufficiently high to initiate a nuclear reaction converting hy- drogen into helium (see review [105]). 8.1 Hayashi Phase The pre-main sequence evolution of stars takes place at not very high temperatures, when a non-full ionization of matter and large opacity cause such stars to be almost convective. This fact was first established by Hayashi [461, 462], who took into account a convection in constructing evolutionary tracks for contracting stars in the HR diagram (see Fig. -

Brightness Profiles of Early-Type Galaxies Hosting Seyfert Nuclei

A&A 469, 75–88 (2007) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361:20066684 & c ESO 2007 Astrophysics The host galaxy/AGN connection Brightness profiles of early-type galaxies hosting Seyfert nuclei A. Capetti and B. Balmaverde INAF - Osservatorio Astronomico di Torino, Strada Osservatorio 20, 10025 Pino Torinese, Italy e-mail: [capetti;balmaverde]@oato.inaf.it Received 2 November 2006 / Accepted 15 March 2007 ABSTRACT We recently presented evidence of a connection between the brightness profiles of nearby early-type galaxies and the properties of the AGN they host. The radio loudness of the AGN appears to be univocally related to the host’s brightness profile: radio-loud nuclei are only hosted by “core” galaxies while radio-quiet AGN are only found in “power-law” galaxies. We extend our analysis here to a −1 sample of 42 nearby (Vrec < 7000 km s ) Seyfert galaxies hosted by early-type galaxies. From the nuclear point of view, they show a large deficit of radio emission (at a given X-ray or narrow line luminosity) with respect to radio-loud AGN, conforming with their identification as radio-quiet AGN. We used the available HST images to study their brightness profiles. Having excluded complex and highly nucleated galaxies, in the remaining 16 objects the brightness profiles can be successfully modeled with a Nuker law with a steep nuclear cusp characteristic of “power-law” galaxies (with logarithmic slope γ = 0.51−1.07). This result is what is expected for these radio-quiet AGN based on our previous findings, thus extending the validity of the connection between brightness profile and radio loudness to AGN of a far higher luminosity. -

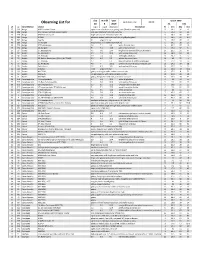

Observing List

day month year Epoch 2000 local clock time: 22.00 Observing List for 20 4 2019 RA DEC alt az Constellation object mag A mag B Separation description hr min deg min 27 293 Auriga M36 Pinwheel Cluster open cluster of a dozen or so young stars (30million years old) 5 36.1 34 8 29 289 Auriga M37 January Salt and Pepper Cluster rich, open cluster of 150 stars, very fine 5 52.4 32 33 27 295 Auriga M38 Starfish Cluster large open cluster 220 million years old 5 28.7 35 50 36 303 Auriga IC2149 planetary nebula, stellar to small disk, slightly elongated 5 56.5 46 6.3 30 307 Auriga Capella 0.1 alignment star 5 16.6 46 0 40 290 Auriga UU Aurigae Magnitude 5.1-7.0 carbon star (AL# 36) 6 36.5 38 27 33 293 Auriga 37 Theta Aurigae 2.6 7.1 3.6 white & bluish stars 5 59.7 37 13 23 294 Auriga 14 Aurigae 5.1 7.4 14.6 pale yellow and blue 5 15.4 32 31 57 56 Bootes 17, Kappa Bootis 4.6 6.6 13.4 bright white primary & bluish secondary 14 13.5 51 47 56 57 Bootes 21, Iota Bootis 4.9 7.5 38.5 wide yellow & blue pair 14 16.2 51 22 38 102 Bootes 29, Pi Bootis 4.9 5.8 5.6 fine bright white pair 14 40.7 16 25 43 90 Bootes 36, Epsilon Bootis (Izar) (*311) (HIP72105) 2.9 4.9 2.8 golden & greenish-blue 14 45 27 4 37 97 Bootes 37, Xi Bootis 4.7 7 6.6 beautiful yellow & reddish orange pair 14 51.4 19 6 41 72 Bootes 51, Mu Bootis 4.3 7 108.3 primary of yellow & close orange BC pair 15 24.5 37 23 41 78 Bootes Delta Bootis 3.5 8.7 105 wide yellow & blue pair 15 15.5 33 19 44 104 Bootes Arcturus -0.11 alignment star 14 15.6 19 10.4 43 124 Bootes NGC5248 galaxy with bright -

![Arxiv:2001.08266V1 [Astro-Ph.SR] 22 Jan 2020](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9958/arxiv-2001-08266v1-astro-ph-sr-22-jan-2020-3879958.webp)

Arxiv:2001.08266V1 [Astro-Ph.SR] 22 Jan 2020

Astronomy & Astrophysics manuscript no. aanda c ESO 2020 January 24, 2020 Searching for central stars of planetary nebulae in Gaia DR2 N. Chornay and N. A. Walton Institute of Astronomy, University of Cambridge, Madingley Road, Cambridge, CB3 0HA, United Kingdom e-mail: [email protected], e-mail: [email protected] January 24, 2020 ABSTRACT Context. Accurate distance measurements are fundamental to the study of Planetary Nebulae (PNe) but have long been elusive. The most accurate and model-independent distance measurements for galactic PNe come from the trigonometric parallaxes of their central stars, which were only available for a few tens of objects prior to the Gaia mission. Aims. Accurate identification of PN central stars in the Gaia source catalogues is a critical prerequisite for leveraging the unprece- dented scope and precision of the trigonometric parallaxes measured by Gaia. Our aim is to build a complete sample of PN central star detections with minimal contamination. Methods. We develop and apply an automated technique based on the likelihood ratio method to match candidate central stars in Gaia Data Release 2 (DR2) to known PNe in the HASH PN catalogue, taking into account the BP–RP colours of the Gaia sources as well as their positional offsets from the nebula centres. These parameter distributions for both true central stars and background sources are inferred directly from the data. Results. We present a catalogue of over 1000 Gaia sources that our method has automatically identified as likely PN central stars. We demonstrate how the best matches enable us to trace nebula and central star evolution and to validate existing statistical distance scales, and discuss the prospects for further refinement of the matching based on additional data. -

Maneuver Estimation Model for Relative Orbit Determination

Air Force Institute of Technology AFIT Scholar Theses and Dissertations Student Graduate Works 3-2005 Maneuver Estimation Model for Relative Orbit Determination Tara R. Storch Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.afit.edu/etd Part of the Astrodynamics Commons Recommended Citation Storch, Tara R., "Maneuver Estimation Model for Relative Orbit Determination" (2005). Theses and Dissertations. 3698. https://scholar.afit.edu/etd/3698 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Graduate Works at AFIT Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of AFIT Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Maneuver Estimation Model for Relative Orbit Determination THESIS Tara R. Storch, Capt, USAF AFIT/GA/ENY/05-M011 DEPARTMENT OF THE AIR FORCE AIR UNIVERSITY AIR FORCE INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, Ohio APPROVED FOR PUBLIC RELEASE; DISTRIBUTION UNLIMITED. The views expressed in this thesis are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the United States Air Force, Department of Defense, or the United States Government. AFIT/GA/ENY/05-M011 Maneuver Estimation Model for Relative Orbit Determination THESIS Presented to the Faculty Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics Graduate School of Engineering and Management Air Force Institute of Technology Air University Air Education and Training Command In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Astronautical Engineering Tara R. Storch, B.S. Capt, USAF March, 2005 APPROVED FOR PUBLIC RELEASE; DISTRIBUTION UNLIMITED. AFIT/GA/ENY/05-M011 Maneuver Estimation Model for Relative Orbit Determination Tara R. -

Nonthermal Particles and Photons in Starburst Regions and Superbubbles

Astron Astrophys Rev (2014) 22:77 DOI 10.1007/s00159-014-0077-8 REVIEW ARTICLE Nonthermal particles and photons in starburst regions and superbubbles Andrei M. Bykov Received: 7 July 2014 / Published online: 14 November 2014 © Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2014 Abstract Starforming factories in galaxies produce compact clusters and loose asso- ciations of young massive stars. Fast radiation-driven winds and supernovae input their huge kinetic power into the interstellar medium in the form of highly supersonic and superalfvenic outflows. Apart from gas heating, collisionless relaxation of fast plasma outflows results in fluctuating magnetic fields and energetic particles. The energetic particles comprise a long-lived component which may contain a sizeable fraction of the kinetic energy released by the winds and supernova ejecta and thus modify the magnetohydrodynamic flows in the systems. We present a concise review of observa- tional data and models of nonthermal emission from starburst galaxies, superbubbles, and compact clusters of massive stars. Efficient mechanisms of particle acceleration and amplification of fluctuating magnetic fields with a wide dynamical range in star- burst regions are discussed. Sources of cosmic rays, neutrinos and multi-wavelength nonthermal emission associated with starburst regions including potential galactic “PeVatrons” are reviewed in the global galactic ecology context. Keywords Starburst · Supernova remnants · Stellar winds · Interstellar medium · Cosmic rays · High energy neutrinos A. M. Bykov (B) Ioffe Institute for Physics and Technology, 194021 St. Petersburg, Russia e-mail: [email protected] A. M. Bykov International Space Science Institute, Bern, Switzerland A. M. Bykov St. Petersburg State Polytechnical University, St. Petersburg, Russia 123 Page 2 of 54 Astron Astrophys Rev (2014) 22:77 1 Introduction Almost 80 years ago W. -

SLOWMO: a Search for Nearby Stars

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Physics and Astronomy Theses Department of Physics and Astronomy 12-3-2007 SLOWMO: A Search for Nearby Stars Misty Adana Brown Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/phy_astr_theses Part of the Astrophysics and Astronomy Commons, and the Physics Commons Recommended Citation Brown, Misty Adana, "SLOWMO: A Search for Nearby Stars." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2007. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/phy_astr_theses/4 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Physics and Astronomy at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Physics and Astronomy Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SLOWMO: A Search for Nearby Stars by Misty Brown Under the Direction of Todd Henry Abstract I report on suspected nearby stars with proper motions 1.000 > µ ≥ 0.500/yr in the southern sky (DEC = −90◦ to 00◦). This sample of slow-motion (SLOWMO) stars complements the work of Jao (2004), who reported on faster moving stars with µ ≥ 1.000/yr in the entire sky for his doctoral dissertation, and the work of Finch et al. (2007), who uncovered stars moving slower than 0.500/yr between declinations −90◦ and −47◦. Characterizations of SLOWMO systems include trigonometric parallaxes, optical and infrared photometry. For stars without trigonometric parallaxes, colors and apparent magnitudes are used to calculate photometric distance estimates and the statistics of this population of stars are analyzed. The SLOWMO sample is comprised of 1906 total stars − 560 estimated to be less than 25 parsecs away, and 245 stars without parallaxes estimated to be within 25 parsecs. -

Message from the Director General SUMMARY of a REPORT to the ESO STAFF

No. 76 - June 1994 Message from the Director General SUMMARY OF A REPORT TO THE ESO STAFF 1. Audit This will not be easy and will require a schedule, if a solution to this critical certain effort from all involved. The team which was charged by the problem is not found soon. The recent visit by the ESO delegation to Chile dur ESO Council to provide an audit report about ESO and in particular the VLT ing which meetings were held with the 2. Chile project, has now finished its work with a Foreign Minister and also the President of the Republic of Chile, reassured us final discussion at the ESO Headquar The situation of ESO in Chile has been that the Chilean Government fully ters on April 28, 1994. The report has the subject of ;llany recent discussions adheres to the conditions laid down in been published and was discussed by and, as is known and has been made the Chile-ESO Treaty, including ESO's Council in its recent meeting. public through recent press releases, immunities and privileges. I am glad to tell you that ESO came ESO appears to be under a concerted In view of the crucial importance of through this exercise "with flying col attack from some groups in that coun the Paranal issue for the VLT project and ours" and that our earlier statements try. While ESO has meticulously ad since we have at this moment commit concerning the work done at ESO were hered to its legal obligations in Chile, it is ted approximately half of the total VLT largely confirmed by the Audit Team. -

The COLOUR of CREATION Observing and Astrophotography Targets “At a Glance” Guide

The COLOUR of CREATION observing and astrophotography targets “at a glance” guide. (Naked eye, binoculars, small and “monster” scopes) Dear fellow amateur astronomer. Please note - this is a work in progress – compiled from several sources - and undoubtedly WILL contain inaccuracies. It would therefor be HIGHLY appreciated if readers would be so kind as to forward ANY corrections and/ or additions (as the document is still obviously incomplete) to: [email protected]. The document will be updated/ revised/ expanded* on a regular basis, replacing the existing document on the ASSA Pretoria website, as well as on the website: coloursofcreation.co.za . This is by no means intended to be a complete nor an exhaustive listing, but rather an “at a glance guide” (2nd column), that will hopefully assist in choosing or eliminating certain objects in a specific constellation for further research, to determine suitability for observation or astrophotography. There is NO copy right - download at will. Warm regards. JohanM. *Edition 1: June 2016 (“Pre-Karoo Star Party version”). “To me, one of the wonders and lures of astronomy is observing a galaxy… realizing you are detecting ancient photons, emitted by billions of stars, reduced to a magnitude below naked eye detection…lying at a distance beyond comprehension...” ASSA 100. (Auke Slotegraaf). Messier objects. Apparent size: degrees, arc minutes, arc seconds. Interesting info. AKA’s. Emphasis, correction. Coordinates, location. Stars, star groups, etc. Variable stars. Double stars. (Only a small number included. “Colourful Ds. descriptions” taken from the book by Sissy Haas). Carbon star. C Asterisma. (Including many “Streicher” objects, taken from Asterism. -

A New Minimization Procedure for Stellar Parameters Using High-Quality Spectra?,??

A&A 600, A69 (2017) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/201629967 & c ESO 2017 Astrophysics SWEET-Cat update and FASMA A new minimization procedure for stellar parameters using high-quality spectra?,?? D. T. Andreasen1; 2, S. G. Sousa1, M. Tsantaki3, G. D. C. Teixeira1; 2, A. Mortier4, N. C. Santos1; 2, L. Suárez-Andrés5; 6, E. Delgado-Mena1, and A. C. S. Ferreira1; 2 1 Instituto de Astrofísica e Ciências do Espaço, Universidade do Porto, CAUP, Rua das Estrelas, 4150-762 Porto, Portugal e-mail: [email protected] 2 Departamento de Física e Astronomia, Faculdade de Ciências, Universidade do Porto, Rua Campo Alegre, 4169-007 Porto, Portugal 3 Instituto de Radioastronomía y Astrofísica, IRyA, UNAM, Campus Morelia, A.P. 3-72, 58089 Michoacán, Mexico 4 Centre for Exoplanet Science, SUPA, School of Physics and Astronomy, University of St Andrews, St Andrews KY16 9SS, UKSUPA, School of Physics and Astronomy, University of St Andrews, St Andrews KY16 9SS, UK 5 Depto. Astrofísica, Universidad de La Laguna (ULL), 38206 La Laguna, Tenerife, Spain 6 Instituto de Astrofísica de Canarias, 38205 La Laguna, Tenerife, Spain Received 27 October 2016 / Accepted 17 January 2017 ABSTRACT Context. Thanks to the importance that the star-planet relation has to our understanding of the planet formation process, the precise determination of stellar parameters for the ever increasing number of discovered extrasolar planets is of great relevance. Furthermore, precise stellar parameters are needed to fully characterize the planet properties. It is thus important to continue the efforts to determine, in the most uniform way possible, the parameters for stars with planets as new discoveries are announced.