Playing to Win, Learning to Lose

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

177 Mental Toughness Secrets of the World Class

177 MENTAL TOUGHNESS SECRETS OF THE WORLD CLASS 177 MENTAL TOUGHNESS SECRETS OF THE WORLD CLASS The Thought Processes, Habits And Philosophies Of The Great Ones Steve Siebold 177 MENTAL TOUGHNESS SECRETS OF THE WORLD CLASS 177 MENTAL TOUGHNESS SECRETS OF THE WORLD CLASS The Thought Processes, Habits And Philosophies Of The Great Ones Steve Siebold Published by London House www.londonhousepress.com © 2005 by Steve Siebold All Rights Reserved. Printed in Hong Kong. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the copyright owner. Ordering Information To order additional copies please visit www.mentaltoughnesssecrets.com or visit the Gove Siebold Group, Inc. at www.govesiebold.com. ISBN: 0-9755003-0-9 Credits Editor: Gina Carroll www.inkwithimpact.com Jacket and Book design by Sheila Laughlin 177 MENTAL TOUGHNESS SECRETS OF THE WORLD CLASS DEDICATION This book is dedicated to the three most important people in my life, for their never-ending love, support and encouragement in the realization of my goals and dreams. Dawn Andrews Siebold, my beautiful, loving wife of almost 20 years. You are my soul mate and best friend. I feel best about me when I’m with you. We’ve come a long way since sub-man. I love you. Walter and Dolores Siebold, my parents, for being the most loving and supporting parents any kid could ask for. Thanks for everything you’ve done for me. -

Revolutionary Leadership Playing to Win the Power of Persuasion Happiness Matters Minimizing Gender Biases in the Workplace

EXECUTIVE BRIEFINGS DVDS AND VIDEO STREAMING NEW SPEAKERS AND BEST SELLERS ISISSSUEUE XXXIIXXXI Revolutionary Playing to Win The Power of Happiness Minimizing A.G. Lafley Leadership Former Chairman Persuasion Matters Gender Biases Gary Hamel and CEO Robert Cialdini Tony Hsieh in the Visiting Professor Procter & Gamble Professor CEO London Business Arizona State Zappos.com, Inc. Workplace School University Roger Martin Shelley Correll Dean Professor Rotman School Stanford of Management University Now You Can Stream Dear Friends, Executive Briefings Each month, we sponsor a business presentation here on the Stanford campus. Business Programs! leaders, academic experts, and renowned consultants provide creative solutions and practical advice for the challenges businesses face today. These engaging, thought-provoking 1-5 users: talks are available to you on DVD or online, giving you quick and easy access. Online Access price $95/program Get both: We’re proud to present new programs of particular interest: Online Access + DVD $139/program • Revolutionary Leadership by Gary Hamel, Visiting Professor, London Business School 6 or more users: (page 3) Online Access price $5.50/user and • Playing to Win: How Strategy Really Works by A.G. Laey, former Chairman and $65 setup fee/program CEO of Procter & Gamble, and Roger L. Martin, Dean, Rotman School of Get both: Online Access Management, University of Toronto (page 9) Online Access + DVD price plus $44/DVD • Minimizing Gender Biases in the Workplace by Stanford Professor Shelley Correll Generate quick quotes for Online (page 15) Access volume discounts at http://info.ExecutiveBriefings.com We also offer you the opportunity to order 10-program Special Collections by discipline, or the entire library of Stanford Executive Briengs on page 7—all at substantial discounts. -

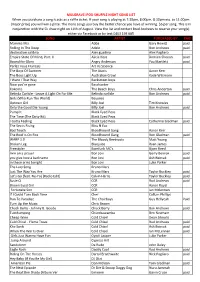

MULGRAVE IPOD SHUFFLE NIGHT SONG LIST When You Purchase a Song It Acts As a Raffle Ticket

MULGRAVE IPOD SHUFFLE NIGHT SONG LIST When you purchase a song it acts as a raffle ticket. If your song is playing at 7:30pm, 8:00pm, 8:30pm etc. to 11:00pm (major prize) you will win a prize. The more songs you buy the better chance you have of winning. $5 per song. This is in conjunction with the 5k draw night on 11th of August. View the list and contact Brad Andrews to reserve your song(s) either via Facebook or by text 0403 193 085 SONG ARTIST PURCHASED BY PAID Mamma Mia Abba Gary Hewitt paid Rolling In The Deep Adele Bon Andrews paid destination calibria Alex guadino Alex Pagliaro Empire State Of Mind, Part. II Alicia Keys Damien Sheean paid Bound for Glory Angry Anderson Paul Bartlett paid Parlez Vous Francais Art Vs Science The Boys Of Summer The Ataris Aaron Kerr The Boys Light Up Australian Crawl Kade Wilsmore I Want I That Way Backstreet boys Now you're gone Basshunter Kokomo The Beach Boys Chris Anderton paid Belinda Carlisle ‐ Leave A Light On For Me Belinda carlisle Bon Andrews paid Girls (Who Run The World) Beyonce Uptown Girl Billy Joel Tim Knowles Only the Good Die Young Billy Joel Bon Andrews paid Pump It Black Eyed Peas The Time (The Dirty Bit) Black Eyed Peas I Gotta Feeling Black Eyed Peas Catherine Gladman paid The Sea is Rising Bliss N Eso Bad Touch Bloodhound Gang Aaron Kerr The Roof Is On Fire Bloodhound Gang Ron Gladman paid WARP 1.9 The Bloody Beetroots Matt Young Broken Leg Bluejuice Ryan James Freestyler Bomfunk MC's Bjorn Reed livin on a prayer Bon Jovi Gerry Beiniak paid you give love a bad name Bon Jovi Ash Beiniak paid in these arms tonight Bon Jovi Luke Parker The Lazy Song Bruno Mars Just The Way You Are Bruno Mars Taylor Buckley paid Let's Go (feat. -

Download the Full Document About Romania

About Romania Romania (Romanian: România, IPA: [ro.mɨni.a]) is a country in Southeastern Europe sited in a historic region that dates back to antiquity. It shares border with Hungary and Serbia to the west, Ukraine and the Republic of Moldova to the northeast, and Bulgaria to the south. Romania has a stretch of sea coast along the Black Sea. It is located roughly in the lower basin of the Danube and almost all of the Danube Delta is located within its territory. Romania is a parliamentary unitary state. As a nation-state, the country was formed by the merging of Moldavia and Wallachia in 1859 and it gained recognition of its independence in 1878. Later, in 1918, they were joined by Transylvania, Bukovina and Bessarabia. At the end of World War II, parts of its territories (roughly the present day Moldova) were occupied by USSR and Romania became a member of Warsaw Pact. With the fall of the Iron Curtain in 1989, Romania started a series of political and economic reforms that peaked with Romania joining the European Union. Romania has been a member of the European Union since January 1, 2007, and has the ninth largest territory in the EU and with 22 million people [1] it has the 7th largest population among the EU member states. Its capital and largest city is Bucharest (Romanian: Bucureşti /bu.kureʃtʲ/ (help·info)), the sixth largest city in the EU with almost 2 million people. In 2007, Sibiu, a large city in Transylvania, was chosen as European Capital of Culture.[2] Romania joined NATO on March 29, 2004, and is also a member of the Latin Union, of the Francophonie and of OSCE. -

Heroes, Conflicts and Reconciliations in Romanian-Hungarian Sport Confrontations

REHIS 2 (1) 2015 Heroes, conflicts and reconciliations in Romanian-Hungarian sport confrontations Pompiliu-Nicolae Constantin* Abstract: Romanians and Hungarians have a long history of rivalry in politics, culture and sport. Rarely, history speaks about symbols of reconciliation, probably because these actors are episodic personalities and because the conflicts are longer and they have a cyclic manifestation. The battle for Transylvania was a permanent subject in the Romania-Hungary relation. Also, the high number of Hungarians ethnics in Romania provoked different attitudes in the last centuries. Sport was one of the newest ways to expose the conflict between the Romanians and the Hungarians. From interwar period until nowadays, sport activities which included these two national groups has generated debates, violence and few moments of reconciliation. In fact, I will follow this last aspect, in the context of an image of permanent conflict, to analyse the importance of some symbols of reconciliation. Keywords: conflict, reconciliation, ethnic groups, supporters, Romanian sport, Hungarian sport The idea of nation is still an active concept in the Romanian-Hungarian relation, especially if we see the problem of Székely Land autonomy 1. The history of these countries has been inter-crossing since the Middle Age and the rivalry has been always animated. According to historian László Kontler, these two nations * Pompiliu-Nicolae Constantin became a doctor in History at the University of Bucharest and doctor in Political Sciences at the Free University of Brussels in 2013. His PhD thesis dealt with the sport stars from the ethnic groups in communist Romania. Starting with February 2014, he is Associate Researcher at CEREFREA (Le Centre Régional Francophone de Recherches Avancées en Sciences Sociales) – University of Bucharest. -

An Examination of Beliefs About Romanian Legislative Regulations Specific to Sports

AN EXAMINATION OF BELIEFS ABOUT ROMANIAN LEGISLATIVE REGULATIONS SPECIFIC TO SPORTS Daniel BRĂTIANU1 Abstract Romanian Sport Legislation is not widely analysed in the literature with regards to the effects it has on the activities specific to sports, its organisations and management of sports entities. There are on the other hand studies in the specialised literature which underline the Legislation gaps, or issues caused by lack of clarity and not in harmony with European Sports Regulations. The actual Romanian legislative regulations specific to Sports needs to be amended to better respond to the sports environment and its needs, leading to higher participation in sport and less litigation. This research was carried out using the questionnaire method, statistical processing and analysis and bibliographic study. The questionnaire was administered online, it consisted of 10 questions, to which the respondents could answer with yes, no or no opinion. The respondents’ answers indicate that they have a positive perspective with regards to changing some of the actual sports regulations. The results showed no significant differences between men and women but found some differences between the levels of studies. The relationship between the answers and the level of studies was significant at p<.05. Keywords: sports legislation, sport regulation, Romanian sports law JEL Classification: Z2, K1; K40 DOI: 10.24818/mrt/2020.0120201 1. Introduction Since the European Union was established, sports regulation has gained an international dimension, but unlike other industries regulated by International Laws, sports is different due to the fact that it has not only an economical dimension, but also a cultural and a social one. -

„Edi Iordănescuva Fi Mourinho!“

AZI MÂINE MÂINE MÂINE MÂINE LUNI LUNI LUNI „U“ CLUJ 1-1 VASLUI 18:00 SPORTUL 14:30 OÞELUL 16:30 PANDURII 18:30 RAPID 20:30 TG. MURE¯ 16:00 BRAOV 18:00 URZICENI 20:00 CFR CLUJ 1-1 BISTRIȚA GSP TV ASTRA GSP TV STEAUA DIGI TIMIOARA GSP TV BRĂNE¯TI DIGI CRAIOVA GSP TV GAZ METAN DIGI DINAMO A1 601.000 DE CITITORI zilnic (SNA) Numărul 4.039 EDIIE NAIONALĂ 1.244.498 DE VIZITATORI unici în iulie (SATI) Sâmbătă, 25 septembrie 2010 Editat de Publimedia International pe www.prosport.ro 16 pagini ∞ Tiraj: 54.084 „Edi Iordănescu va fi Mourinho!“ Alin Stoica, prietenul din copilărie al actualului principal de la Steaua, e convins că fiul Generalului va ajunge un mare ȘTIM CE ÎNSEAMNĂ SĂ FII SUPORTER antrenor ª Iordănescu jr, primit excelent de A văzut pe viu ultimele 79 de derby-uri Steaua - Dinamo vestiar: „superbăiat, Sergiu Ioan, unul dintre cei mai înfocaßi fani ai „câinilor“, »6-7 caracter și n-are aere“ se simte jignit de ultimele declarații ale lui Andone de MURE¯ANU »2-3 de VLAD „U“CLUJ 1 CFR CLUJ 1 Campioana, un punct în trei etape!! REFUZAT DE STEAUA, »8-9 BUN DE VASLUI Meme Stoica a ajuns în ograda lui Porumboiu ª Are obiectiv SUPERFILM ÎN locul 1 ª Îi aduce pe Levi și Maftei GHENCEA Nicolas Cage, la Steaua! »16 ÎNÞELEGERE ¯tim ce înseamnă să fii suporter să fii ce înseamnă ¯tim Corespondentul ProSport a surprins ieri momentul în care Porumboiu INTERVIU a bătut palma cu EVENIMENT CU Mihai Stoica, la WILANDER sediul Comcereal De ce n-are Vaslui „ouă“ Federer »15 www.prosport.ro MOURINHO IESE LA ATAC Barcelona, acuzată de blat PREÞ: 1,8 lei Foto: Vremea Nouă (Vaslui) »13 »11 de GHEORGHIU 02 Sâmbătă 25 septembrie 2010 SITUAȚIE / EDI IORDĂNESCU A CUCERIT VESTIARUL DIN GHENCEA ÎN POSTURA DE ANTRENOR PRINCIPAL STEAUA www.prosport.ro A fi ipocrit OPINIE să spun că Dan nu vorbesc FILOTI CORNER cu tata. -

Pag 9 Indd NOU.Indd

Vineri, 14 aprilie 2017 Sport 9 CN de polo pentru juniori I CS Oşorhei – ACSF Comuna Recea N-au voie să piardă Clasată în zona „nisipurilor mişcătoare”, Crişul Oradea este echipa pregătită de Gheorghe Silaghi nu are voie să facă niciun pas greşit în duelul cu a treia clasată. Disputa CS Oşorhei – ACSFC Recea, contând pentru etapa a 23-a din Seria a 5-a a Ligii a III-a, are loc astăzi, de campioana României la ora 17.00, pe terenul din Alparea. Bazinul Olimpic „Ioan meş şi Victor Kovats, care au Fără a arăta o formă deosebită în acest sezon Alexandrescu” a găzduit jo- evoluat în acest sezon pentru de primăvară, cu rezultate modeste înregis- curile ultimului turneu fi nal CSM Digi Oradea în Superli- trate în deplasare, echipa maramureşeană ar din cadrul Campionatului ga Naţională. Nici Steaua nu putea fi accesibilă în acest context pentru cei Naţional de polo pentru ju- a stat mai rău la acest capitol, din Oşorhei. Totuşi, nu trebuie omis faptul că niori I. La capătul unei com- orădeanul Cosmin Goina, an- ACSF Comuna Recea este a treia clasată, la petiţii în care titlul s-a decis trenorul echipei din Capitală, egalitate de puncte cu Metalurgistul Cugir, în ultima partidă, formaţia avându-i la dispoziţie pe Vlad formaţia de pe locul al doilea. În acelaşi timp, pregătită de Ciprian Cîmpi- Georgescu şi Victor Antipa, elevii lui Gheorghe Silaghi vin după o corecţie anu a izbutit să cucerească golgeterii turneului înaintea severă (0-4) suferită în runda precedentă în titlul de campioană naţiona- duelului pentru titlu. -

Romania Soccer Players and Footballers Hard 5059.Pdf

Romania Soccer Players and Footballers - Free Printable Wordsearch CRFPPMWCYALEXANDRUAPO LZANQNQHXXP HRAZVANCOCISALEXANDR UCHIPCIUFVRQ JOZSEFPECSOVSZKYEFL ORINHALAGIANH VROMTXDLDGZWCVIOANLUP ESCUAOHVLRF ZEZANUSIJISZINQHXH ELMUTHDUCKADAM XJXRWNXZNMPPPCLAUDIU BUMBASEKDWIP BTMCFBTZQUICRKDAPCPN ICOLAEDICAPD RZLEEQFMQLSOIECXHAOX OKQRHYXVJMLC CKCLGKYAIWMAAIRPFCAD RIANMUTUOXIS SVWRBTDFIQXLNKXHTJOY OPIONUTNEAGU AQAAOJNRKDUOTMGABIBA LINTIKTKWUID BGBDSAIOVCRYAZAMIRCE ALUCESCUQOYA AIDUIPUMIDKKTBZRIL IEDUMITRESCUMD CDXCCALNNTUYAARGTRSOZ LEVXPFEXUIR SFUAQSLAAEJORHHLBEME RICHJENEIIMI ILHNJENRNWKAUFEAAGAC GZUCDZOQSUWA ZNMUIAAOGAVBSNGTBIEN OCQHBVCOXDHN MBTNIBDGHLMZAERTLAJ OSSATMAREANUC AAARUNTREETVNUXOIENE RRMAOIWPFURR DDOIALIALXRUUNRCTBG EEGEIHKTMCASI IDLNTATZIAMBDFIEIR ELLLECNZGSHCZS AUAHWSUVONSUMOFCOPLRRN OOTCESATUT IOSAZZSARDDAGHREOURU INIRGBOKATVE IJWZWLONDEIAIUGESLB IAUACMAUNIGXA LHFTWOZRARDDNURSLSAVAW GUOLRMTCAL OKQKHBOANVKYDIUBNSZEH NBHRLUAURWI KNIRZONTEEWUOIEIOAT CKNMEIRIMRWAN LDJWGLRRSNDPRMRLRLSOA OMATOZTRUZT RNFHSOQYCCJANBFULKOI IAVIRQAFAKAO IPHFCNTRUEMFAWNQEURHH CMAYIPNCOGS ABVTNIQNOLOSBRJLKDN IAUAVCQCYEZZC BDJFPOCPVULSHLEAAKT GDNTNISPAANQA CIPRIAN TATARUSANU TIBERIU GHIOANE CIPRIAN MARICA NICOLAE DICA JOZSEF PECSOVSZKY FLORIN HALAGIAN BANEL NICOLITA IOAN LUPESCU ANGHEL IORDANESCU DINU SANMARTEAN NICOLAE KOVACS LUCIAN FILIP GABRIEL PARASCHIV ILIE DUMITRESCU DUDU GEORGESCU DUMITRU MITU ALEXANDRU CHIPCIU ADRIAN BUMBESCU LASZLO BOLONI RAZVAN COCIS ALEXANDRU APOLZAN MARCEL RADUCANU CLAUDIU BUMBA GABI BALINT LAJOS SATMAREANU TUDOREL STOICA COSMIN -

Kevin Smith 2021 Speaker's Packet

Kevin Smith 2021 Speaker’s Packet Part of the Equation for Creating Successful Financial Institutions Contact information: [email protected] 608-217-0556 Biography of Kevin Smith Kevin Smith is Consultant and Publisher with TEAM Resources. He brings extensive experience in training, designing and implementing professional development resources to nourish the growth of leaders within the credit union industry. Kevin facilitates strategic planning processes, teaches Strategic Governance to Boards of Directors, and oversees the TEAM Resources board self- evaluation programs with credit unions nationwide. Kevin is co-author of A Credit Union Guide to Strategic Governance. This essential book helps Governance teams become as effective as possible. He also writes the monthly TEAM Resources blog that is read by thousands nationally. The monthly blog shares guidance on board topics such as governance, strategy and issues related to the supervisory committee. Previously, Kevin spent 10 years at the Credit Union National Association (CUNA), in the Center for Professional Development as Director of Volunteer Education. In that role Kevin developed and oversaw programs for credit union executives, boards, and volunteers. This included conferences and training events, webinars, print programs, and online courses, among others. During his tenure at CUNA, he created and brought several new programs to the credit union movement. One of these is the CUNA Volunteer Certification Program, an intensive, competency-based program for boards and supervisory committees, offered as a five-day onsite event or as a self-study program, both involving rigorous testing for completion. He also created the CUNA Training On Demand series of downloadable training courses, and the CUNA Pressing Economic Issues series featuring the CUNA economists. -

183 from Performance Sports to Sports for All: Romania 1945-1965

ISSN2039Ͳ9340MediterraneanJournalofSocialSciencesVol.3(10)July2012 From Performance Sports to Sports for All: Romania 1945-1965. Legal Aspects Alexandru -Rares PUNI Assistant Professor, Faculty of Physical Education and Sports ”Alexandru Ioan Cuza” University - Iasi, Romania [email protected] Abstract: The establishment of the communist regime in Romania in 1945 marked the beginning of a series of profound transformations in the Romanian political and social life. These changes also affected the field of sports activities, which were, at the time, at the initial point of their institutional organization.Our research aims at analyzing, in a critical manner, the main legislative regulations regarding sports life implemented between 1945-1965. Their main goal was to promote the benefits of practicing physical activities regularly, not only by performance sportsmen, but also by the majority of the population. This initiative matched the international tendency commonly called “sports for all”, advertised by the founding-father of modern Olympic games – Pierre de Coubertin. The laws issued by the communist authorities stipulated the establishment of national institutions and organizations in charge with the situation of the Romanian sports field, with the financial aspects requested by such endeavor and with the funding provided by the government. Unfortunately, many of the objectives formulated in these laws were left only in their initial form or were completed much later that initially intended. Key words: performance sports, mass sport, communist regime, Romania. Introduction The present study aims to briefly present the main legal regulations directly related to physical activities and sports that were promoted in Romania by the Communist authorities between 1945 and 1965. -

Sport Fans' Motivations: an Investigation of Romanian Soccer

Journal of International Business and Cultural Studies Sport fans’ motivations: an investigation of Romanian soccer spectators G. Martin Izzo, PhD North Georgia College & State University, Dahlonega, Georgia, USA Corneliu Munteanu, PhD Alexandru Ioan Cuza University, Iasi, Romania Barry E. Langford, DBA University of Mississippi, Oxford, Mississippi, USA Ciprian Ceobanu, PhD Alexandru Ioan Cuza University, Iasi, Romania Iulian Dumitru, PhD Alexandru Ioan Cuza University, Iasi, Romania Florin Nichifor, PhD Alexandru Ioan Cuza University, Iasi, Romania ABSTRACT The purpose of the present study was to add to the existing spectator motivations literature (e.g. Kim, Greenwell, Andrew, Lee & Mahony, 2008; Won and Kitamura 2007; Trail and James 2001; Funk, Mahony, Nakazawa, and Hirakawa 2001) by investigating the buyer motivations of Romanian sport fans. In response to the suggestions of earlier researchers concerning new research that spans across different countries and cultures, the present study seeks to explore sports fans’ motivations in Romania. To respond to sport consumers and develop effective communication strategies requires marketers to investigate spectator motivations to better understand this type of buyer behavior. The present study investigated the motivations of Romanian sport fans toward soccer by adopting and reinterpreting scales of earlier studies. The investigative procedures were very similar to those reported in earlier research (e.g. Kim, Greenwell, Andrew, Lee & Mahony, 2008; Won and Kitamura, 2007; Trail and James, 2001; Funk, Mahony, Nakazawa, and Hirakawa, 2001, etal), who have investigated similar phenomena and developed fans’ spectator motivation scales. The study will further the understanding of the constructs that affect sport fans’ consumption motivations. Although, the present study appears to be somewhat supportive of the work of earlier researchers of sport fan motivation scales, the findings suggest that more analysis is needed.