(Mii-Vitalise) to Support People with Multiple Sclerosis to Be Active - a Pilot Evaluation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wii-Workouts on Chronic Pain, Physical Capabilities and Mood of Older Women: a Randomized Controlled Double Blind Trial

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Repositório Científico do Instituto Politécnico do Porto Wii-Workouts on Chronic Pain, Physical Capabilities and Mood of Older Women: A Randomized Controlled Double Blind Trial Renato Sobral Monteiro-Junior; Cíntia Pereira de Souza; Eduardo Lattari; Nuno Barbosa Ferreira Rocha; Gioia Mura; Sérgio Machado; Elirez Bezerra da Silva Abstract Chronic Low Back Pain (CLBP) is a public health problem and older women have higher incidence of this symptom, which affect body balance, functional capacity and behavior. The purpose of this study was to verifying the effect of exercises with Nintendo Wii on CLBP, functional capacity and mood of elderly. Thirty older women (68 ± 4 years; 68 ± 12 kg; 154 ± 5 cm) with CLBP participated in this study. Elderly individuals were divided into a Control Exercise Group (n = 14) and an Experimental Wii Group (n = 16). Control Exercise Group did strength exercises and core training, while Experimental Wii Group did ones additionally to exercises with Wii. CLBP, balance, functional capacity and mood were assessed pre and post training by the numeric pain scale, Wii Balance Board, sit to stand test and Profile of Mood States, respectively. Training lasted eight weeks and sessions were performed three times weekly. MANOVA 2 x 2 showed no interaction on pain, siting, stand-up and mood (P = 0.53). However, there was significant difference within groups (P = 0.0001). ANOVA 2 x 2 showed no interaction for each variable (P > 0.05). However, there were significant differences within groups in these variables (P < 0.05). -

Influence of the Use of Wii Games on Physical Frailty Components

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health Article Influence of the Use of Wii Games on Physical Frailty Components in Institutionalized Older Adults Jerónimo J. González-Bernal 1 , Maha Jahouh 1,* , Josefa González-Santos 1,*, Juan Mielgo-Ayuso 1,* , Diego Fernández-Lázaro 2,3 and Raúl Soto-Cámara 1 1 Department of Health Sciences, University of Burgos, 09001 Burgos, Spain; [email protected] (J.J.G.-B.); [email protected] (R.S.-C.) 2 Department of Biochemistry, Molecular Biology and Physiology, Faculty of Health Sciences, Campus of Soria, University of Valladolid, 42003 Soria, Spain; [email protected] 3 Neurobiology Research Group, Faculty of Medicine, University of Valladolid, 47005 Valladolid, Spain * Correspondence: [email protected] (M.J.); [email protected] (J.G.-S.); [email protected] (J.M.-A.) Abstract: Aging is a multifactorial physiological phenomenon in which cellular and molecular changes occur. These changes lead to poor locomotion, poor balance, and an increased falling risk. This study aimed to determine the impact and effectiveness of the use of the Wii® game console on improving walking speed and balance, as well as its influence on frailty levels and falling risk, in older adults. A longitudinal study was designed with a pretest/post-test structure. The study population comprised people over 75 years of age who lived in a nursing home or attended a day care center (n = 80; 45 women; 84.2 ± 8.7 years). Forty of them were included in the Wii group (20 rehabilitation sessions during 8 consecutive weeks), and the other 40 were in the control group. -

Wii Fit– Or Just a Wee Bit?

Wii Fit– Or Just A Wee Bit? By Alexa Carroll, M.S., ast Christmas, Chris Lee and his wife Julie bought a Nintendo Wii John Porcari, Ph.D., video game system as a gift for their three kids, ages 4 to 9. It was and Carl Foster, Ph.D., an immediate hit with the family, and soon after, they also pur- with Mark Anders Lchased Wii Fit, an exer-game for the Wii that focuses on strength training, aerobics, yoga and balance games performed using a small white balance board that looks similar to a household body-weight scale. “It sounded like a fun way to get the kids to of all time. These stats are encouraging, given the exercise and become aware of fitness without well-publicized epidemic of childhood obesity in being draconian or burdensome,” recalls Chris. our country and the fact that obesity and its com- “My oldest daughter took to it right away. My plications cause as many as 300,000 premature wife and I came around a bit more slowly after deaths each year, second only to cigarette smoking watching and helping the kids.” as a cause of death. For the past nine months, the Lees have used Now, assuming folks are using the Wii Fit exer- Wii Fit at least a few times a week, doing yoga, game as a substitute for their normally sedentary weighing in, charting their fitness progress, and screen-time, these numbers are good news. But having family challenges in ski jumping and on just how good? To give the public perspective on the rope course balance games. -

A Pilot Trial of a Videogame-Based Exercise Program for Methadone Maintained Patients

Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 47 (2014) 299–305 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment Brief article A pilot trial of a videogame-based exercise program for methadone maintained patients Christopher J. Cutter, Ph.D. a,b,⁎, Richard S. Schottenfeld, M.D. a, Brent A. Moore, Ph.D. a, Samuel A. Ball, Ph.D. a, Mark Beitel, Ph.D. a,b, Jonathan D. Savant, B.S. b, Matthew A. Stults-Kolehmainen, Ph.D. c, Christopher Doucette, B.A. b, Declan T. Barry, Ph.D. a,b a Yale University School of Medicine, Department of Psychiatry, New Haven, CT 06511 United States b Pain Treatment Services, APT Foundation, Inc., New Haven, CT 06519 United States c Northern Illinois University, IL 60115 United States article info abstract Article history: Few studies have examined exercise as a substance use disorder treatment. This pilot study investigated the Received 23 October 2013 feasibility and acceptability of an exercise intervention comprising the Wii Fit Plus™ and of a time-and- Received in revised form 7 May 2014 attention sedentary control comprising Wii™ videogames. We also explored their impact on physical activity Accepted 12 May 2014 levels, substance use, and psychological wellness. Twenty-nine methadone-maintained patients enrolled in an 8-week trial were randomly assigned to either Active Game Play (Wii Fit Plus™ videogames involving Keywords: ™ Opioid-related disorders physical exertion) or Sedentary Game Play (Wii videogames played while sitting). Participants had high Exercise satisfaction and study completion rates. Active Game Play participants reported greater physical activity Video games outside the intervention than Sedentary Game Play participants despite no such differences at baseline. -

Validity and Reliability of Wii Fit Balance Board for the Assessment of Balance of Healthy Young Adults and the Elderly

J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 25: 1251–1253, 2013 Validity and Reliability of Wii Fit Balance Board for the Assessment of Balance of Healthy Young Adults and the Elderly WEN-DIEN CHANG, PhD1), WAN-YI CHANG, MS2), CHIA-LUN LEE, PhD3), CHI-YEN FENG, MD4)* 1) Department of Sports Medicine, China Medical University, Taiwan (ROC) 2) Graduate Institute of Networking and Multimedia, National Taiwan University, Taiwan (ROC) 3) Center for General Education, National Sun Yat-sen University, Taiwan (ROC) 4) Department of General Surgery, Da Chien General Hospital: No. 36, Gongjing Road, Miaoli City, Miaoli County, Taiwan (ROC) Abstract. [Purpose] Balance is an integral part of human ability. The smart balance master system (SBM) is a balance test instrument with good reliability and validity, but it is expensive. Therefore, we modified a Wii Fit bal- ance board, which is a convenient balance assessment tool, and analyzed its reliability and validity. [Subjects and Methods] We recruited 20 healthy young adults and 20 elderly people, and administered 3 balance tests. The corre- lation coefficient and intraclass correlation of both instruments were analyzed. [Results] There were no statistically significant differences in the 3 tests between the Wii Fit balance board and the SBM. The Wii Fit balance board had a good intraclass correlation (0.86–0.99) for the elderly people and positive correlations (r = 0.58–0.86) with the SBM. [Conclusions] The Wii Fit balance board is a balance assessment tool with good reliability and high validity for elderly people, and we recommend it as an alternative tool for assessing balance ability. -

Nintendo's Wii Fit Overestimates Distance

Science and Technology How Far Did Wii Run? Nintendo’s Wii Fit Overestimates Distance Shayna Moratt*, Carmen B. Swain Department of Exercise Science, The Ohio State University College of Education and Human Ecology ‘Exergaming’ (performing exercise utilizing an interactive video game) has become a popular form of physical activity. Some exergames are specifi- cally aimed at improving or maintaining physical fitness. Yet, there is little information available to describe the accuracy of feedback given to partic- ipants. PURPOSE: To examine the reported run distance and exercise in- tensity elicited by the Wii Fit aerobic free run. METHODS: 500 participants ages 10- 49 completed the Wii Fit aerobic free run. Oxygen consumption (VO2) was measured. Relative oxygen consumption values were used to determine estimated run distance based upon American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) metabolic equations. Subjects rated perceived exertion using Borg’s scale at a period of every 5 minutes.RESULTS: The Wii Fit overestimated the distance of the aerobic free run by a percentage differ- ence of 49.9 ± 15.7 percent. The average VO2 during the free run was 22.3 ± 5.8 ml/kg/min or 6.4 ± 1.7 METs, which is considered vigorous in- tensity by ACSM standards. The mean RPE recorded was 12.43 ± 2.46. CONCLUSIONS: The Wii Fit displays an overestimated figure for dis- tance when performing the aerobic free run. However, the general level of intensity in this sizeable population shows promise as a method of ex- ercise appropriate to improve or maintain fitness in various populations. Introduction BASS, 2010). Frequent participation in physi- About the Author: Physical activity is defined as any body cal activity contributes to ones physical fitness. -

THE EFFECTS of the WII FIT PLUS on BONE MINERAL DENSITY and FLEXIBILITY in ADULTS a Thesis Presented to the Graduate Faculty Of

THE EFFECTS OF THE WII FIT PLUS ON BONE MINERAL DENSITY AND FLEXIBILITY IN ADULTS A Thesis Presented to The Graduate Faculty of The University of Akron In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science Nicholas T. Potenzini May, 2011 THE EFFECTS OF THE WII FIT PLUS ON BONE MINERAL DENSITY AND FLEXIBILITY IN ADULTS Nicholas T. Potenzini Thesis Approved: Accepted: __________________________ __________________________ Advisor Dean of the College Dr. Judith Juvancic-Heltzel Dr. Mark Shermis __________________________ __________________________ Committee Member Dean of the Graduate School Dr. Ronald Otterstetter Dr. George Newkome __________________________ __________________________ Committee Member Date Rachele Kappler __________________________ Department Chair Dr. Victor Pinheiro ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF TABLES………………………………………………………………………..v LIST OF FIGURES………………………………………………………………………vi CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTION……………………………………………………….……….......1 II. REVIEW OF LITERATURE……………………………..…………….………..….. 4 III. METHODS……………………………………...…………………………….….…. 8 Participants……………………………….…………………..…………………..8 Program Design………………………………………………..….………….….11 Statistical Design……………………………………….…………..……….…...13 IV. RESULTS……………………………………………...………………….……..…..14 V. SUMMARY………………………………………...………………………..………18 REFERENCES……………………………………………………………………..……21 APPENDICES .................................................................................................................. 24 Appendix A. Human Subjects Approval Form………………………………… 26 Appendix -

Nintendo Wii Versus Resistance Training to Improve Upper-Limb Function in Children Ages 7 to 12 with Spastic Hemiplegic Cerebral Palsy: a Home-Based Pilot Study

Nintendo Wii versus Resistance Training to Improve Upper-Limb Function in Children Ages 7 to 12 with Spastic Hemiplegic Cerebral Palsy: A Home-Based Pilot Study By Caroline Kassee A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Health Sciences In The Faculty of Health Sciences Kinesiology University of Ontario Institute of Technology July 2015 © Caroline Kassee, 2015 ii CERTIFICATE OF APPROVAL Caroline Kassee (2015) iii Nintendo Wii versus Resistance Training to Improve Upper- Limb Function in Children Ages 7 to 12 with Spastic Hemiplegic Cerebral Palsy: A Home-Based Pilot Study Chairperson of the Supervisory Committee: Dr. Meghann Lloyd Faculty of Health Sciences Abstract This pilot, home-based study compared a Nintendo Wii intervention to a single-joint upper-limb resistance training of a similar intensity, in n=6 children ages of 7 to 12 with spastic hemiplegic CP with respect to upper limb function, compliance and motivation levels. The main results of this study found that all participants in the Wii intervention group (n=3) experienced positive changes in more than one assessment from pre-test to follow-up, and these changes were on average greater than those experienced by the resistance training group (n=3). Also, the Nintendo Wii group was found to have a higher compliance rate with the study’s protocols, and higher parent-reported motivation levels throughout the study, as compared to the resistance-training group. This suggests that Nintendo Wii interventions for the upper limbs may be a more effective home-based rehabilitation strategy than the single-joint upper limb resistance training program used in this study for this population, primarily due to greater participant motivation to comply with Nintendo Wii training. -

Name of Article Author; Year of Publication Type of Gaming

Name of Author; Year Type of gaming Length of Process how its Who can access it Type of How often If a research article is Article of Intervention time for delivered content gaming retrieved (what is Publication intervent delivered intervention measured? i.e. ion can be behaviour, delivery accessed knowledge, symptoms etc.) A feasibility Joo et al.; The Nintendo 2 weeks The Wii detects Patients of the study The player uses 6 sessions per Outcome measures study using 2010 Wii™ (NW) per specific after stroke with part or whole day for 30 include a interactive gaming system, patient movements and upper limb of the upper minutes questionnaire, Fugl- commercial was used for this acceleration in 3 weakness. The limb to Meyer Assessment off-the-shelf study, as it detects dimensions, via a patients were perform tasks of Upper Limb Motor computer the user’s wireless handheld recruited from the (e.g. swinging a Function and visual gaming in movement and pointing device. It inpatient virtual tennis analogue scale of upper limb acceleration in 3 is held by the user, rehabilitation unit of racket or upper limb pain. rehabilitation dimensions using and a sensor bar a Singapore throwing a in patients a wireless connected to the Rehabilitation virtual bowling after stroke. handheld pointing console. Different Centre. Patients were ball). The device (Wiimote) games are included if they were games are housing a designed to test less than 3 months designed to be gyroscope and an the skills of the post-stroke, had fun and accelerometer. user in executing Medical Research interactive, Using various and acceleration of Council motor power with scores and commercially the upper limbs as of at least grade 2 in various available games specified by the the hemiplegic upper motivational (including sports games. -

Physical Rehabilitation with Virtual Reality and Wii Peripherals

Lean on Wii: Physical Rehabilitation With Virtual Reality and Wii Peripherals Fraser ANDERSON1, Michelle ANNETT, Walter F. BISCHOF Department of Computing Science, University of Alberta Abstract. In recent years, a growing number of occupational therapists have integrated video game technologies, such as the Nintendo Wii, into rehabilitation programs. ‘Wiihabilitation’, or the use of the Wii in rehabilitation, has been successful in increasing patients’ motivation and encouraging full body movement. The non-rehabilitative focus of Wii applications, however, presents a number of problems: games are too difficult for patients, they mainly target upper-body gross motor functions, and they lack support for task customization, grading, and quantitative measurements. To overcome these problems, we have designed a low-cost, virtual-reality based system. Our system, Virtual Wiihab, records performance and behavioral measurements, allows for activity customization, and uses auditory, visual, and haptic elements to provide extrinsic feedback and motivation to patients. Keywords. Virtual rehabilitation, tele-rehabilitation, virtual reality, Nintendo Wii Introduction The use of low-cost, commercial gaming systems for rehabilitation has received substantial attention in the last few years. Systems such as the Nintendo Wii encourage players to use natural actions to play games (e.g., swinging the arm to roll a bowling ball, or jogging in place to make a virtual character run). The Wii (and similar systems) has been integrated into rehabilitation programs [1] and has gained the support of occupational therapists because it is easy to use and has a wide variety of games available. While the Wii does have benefits, the games are not designed specifically for rehabilitation, leading the Wii to have many limitations: it cannot accurately monitor and track patients’ progress, games are often too difficult for patients, and there is a lack of appropriate and motivating feedback for patients. -

Exergames to Prevent the Secondary Functional Deterioration of Older Adults During Hospitalization and Isolation Periods During the COVID-19 Pandemic

sustainability Article Exergames to Prevent the Secondary Functional Deterioration of Older Adults during Hospitalization and Isolation Periods during the COVID-19 Pandemic Ana Isabel Corregidor-Sánchez 1,2 , Begoña Polonio-López 1,2,* , José Luis Martin-Conty 1,2 , Marta Rodríguez-Hernández 1,2 , Laura Mordillo-Mateos 1,2 , Santiago Schez-Sobrino 3 and Juan José Criado-Álvarez 4 1 Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Castilla-La Mancha, Av. Real Fábrica de Sedas, s/n, 45600 Talavera de la Reina, Spain; [email protected] (A.I.C.-S.); [email protected] (J.L.M.-C.); [email protected] (M.R.-H.); [email protected] (L.M.-M.) 2 Technological Innovation Applied to Health Research Group (ITAS), Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Castilla-La Mancha, Av. Real Fábrica de Sedas, s/n, 45600 Talavera de la Reina, Spain 3 Faculty of Computer Science, University of Castilla-La Mancha, Paseo de la Universidad 4, 13071 Ciudad Real, Spain; [email protected] Citation: Corregidor-Sánchez, A.I.; 4 Department of Public Health, Institute of Health Sciences, 45600 Talavera de la Reina, Spain; Polonio-López, B.; Martin-Conty, J.L.; [email protected] Rodríguez-Hernández, M.; * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +34-925721010 (ext. 5623) Mordillo-Mateos, L.; Schez- Sobrino, S.; Criado-Álvarez, J.J. Abstract: The COVID-19 pandemic is having an intense impact on the functional capacity of older Exergames to Prevent the Secondary adults, making them more vulnerable to frailty and dependency. The development of preventive and Functional Deterioration of Older rehabilitative measures which counteract the consequences of confinement or hospitalization is an Adults during Hospitalization and urgent need. -

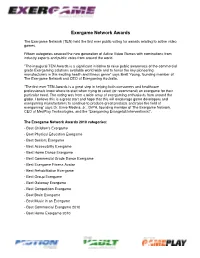

Exergame Network Awards

Exergame Network Awards The Exergame Network (TEN) held the first ever public voting for awards relating to active video games. Fifteen categories covered the new generation of Active Video Games with nominations from industry experts and public votes from around the world. ”The inaugural TEN Awards is a significant initiative to raise public awareness of the commercial grade Exergaming solutions available world wide and to honor the key pioneering manufacturers in this exciting health and fitness genre” says Brett Young, founding member of The Exergame Network and CEO of Exergaming Australia. ”The first ever TEN Awards is a great step in helping both consumers and healthcare professionals know where to start when trying to select (or recommend) an exergame for their particular need. The voting was from a wide array of exergaming enthusiasts from around the globe. I believe this is a great start and hope that this will encourage game developers and exergaming manufacturers to continue to produce great products and raise the field of exergaming” says Dr. Ernie Medina, Jr., DrPH, founding member of The Exergame Network, CEO of MedPlay Technologies, and the “Exergaming Evangelist/Interventionist”. The Exergame Network Awards 2010 categories: - Best Children's Exergame - Best Physical Education Exergame - Best Seniors Exergame - Best Accessibility Exergame - Best Home Dance Exergame - Best Commercial Grade Dance Exergame - Best Exergame Fitness Avatar - Best Rehabilitation Exergame - Best Group Exergame - Best Gateway Exergame - Best Competition Exergame - Best Brain Exergame - Best Music in an Exergame - Best Commercial Exergame 2010 - Best Home Exergame 2010 1. Best Children’s Exergame Award that gets younger kids moving with active video gaming - Dance Dance Revolution Disney Grooves by Konami - Wild Planet Hyper Dash - Atari Family Trainer - Just Dance Kids by Ubisoft - Nickelodeon Fit by 2K Play Dance Dance Revolution Disney Grooves by Konami 2.