Why Do Wii Teach PE

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UPC Platform Publisher Title Price Available 730865001347

UPC Platform Publisher Title Price Available 730865001347 PlayStation 3 Atlus 3D Dot Game Heroes PS3 $16.00 52 722674110402 PlayStation 3 Namco Bandai Ace Combat: Assault Horizon PS3 $21.00 2 Other 853490002678 PlayStation 3 Air Conflicts: Secret Wars PS3 $14.00 37 Publishers 014633098587 PlayStation 3 Electronic Arts Alice: Madness Returns PS3 $16.50 60 Aliens Colonial Marines 010086690682 PlayStation 3 Sega $47.50 100+ (Portuguese) PS3 Aliens Colonial Marines (Spanish) 010086690675 PlayStation 3 Sega $47.50 100+ PS3 Aliens Colonial Marines Collector's 010086690637 PlayStation 3 Sega $76.00 9 Edition PS3 010086690170 PlayStation 3 Sega Aliens Colonial Marines PS3 $50.00 92 010086690194 PlayStation 3 Sega Alpha Protocol PS3 $14.00 14 047875843479 PlayStation 3 Activision Amazing Spider-Man PS3 $39.00 100+ 010086690545 PlayStation 3 Sega Anarchy Reigns PS3 $24.00 100+ 722674110525 PlayStation 3 Namco Bandai Armored Core V PS3 $23.00 100+ 014633157147 PlayStation 3 Electronic Arts Army of Two: The 40th Day PS3 $16.00 61 008888345343 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed II PS3 $15.00 100+ Assassin's Creed III Limited Edition 008888397717 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft $116.00 4 PS3 008888347231 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed III PS3 $47.50 100+ 008888343394 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed PS3 $14.00 100+ 008888346258 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Brotherhood PS3 $16.00 100+ 008888356844 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Revelations PS3 $22.50 100+ 013388340446 PlayStation 3 Capcom Asura's Wrath PS3 $16.00 55 008888345435 -

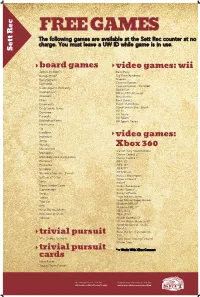

Sett Rec Counter at No Charge

FREE GAMES The following games are available at the Sett Rec counter at no charge. You must leave a UW ID while game is in use. Sett Rec board games video games: wii Apples to Apples Bash Party Backgammon Big Brain Academy Bananagrams Degree Buzzword Carnival Games Carnival Games - MiniGolf Cards Against Humanity Mario Kart Catchphrase MX vs ATV Untamed Checkers Ninja Reflex Chess Rock Band 2 Cineplexity Super Mario Bros. Crazy Snake Game Super Smash Bros. Brawl Wii Fit Dominoes Wii Music Eurorails Wii Sports Exploding Kittens Wii Sports Resort Finish Lines Go Headbanz Imperium video games: Jenga Malarky Mastermind Xbox 360 Call of Duty: World at War Monopoly Dance Central 2* Monopoly Deal (card game) Dance Central 3* Pictionary FIFA 15* Po-Ke-No FIFA 16* Scrabble FIFA 17* Scramble Squares - Parrots FIFA Street Forza 2 Motorsport Settlers of Catan Gears of War 2 Sorry Halo 4 Super Jumbo Cards Kinect Adventures* Superfection Kinect Sports* Swap Kung Fu Panda Taboo Lego Indiana Jones Toss Up Lego Marvel Super Heroes Madden NFL 09 Uno Madden NFL 17* What Do You Meme NBA 2K13 Win, Lose or Draw NBA 2K16* Yahtzee NCAA Football 09 NCAA March Madness 07 Need for Speed - Rivals Portal 2 Ruse the Art of Deception trivial pursuit SSX 90's, Genus, Genus 5 Tony Hawk Proving Ground Winter Stars* trivial pursuit * = Works With XBox Connect cards Harry Potter Young Players Edition Upcoming Events in The Sett Program your own event at The Sett union.wisc.edu/sett-events.aspx union.wisc.edu/eventservices.htm. -

Influence of the Use of Wii Games on Physical Frailty Components

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health Article Influence of the Use of Wii Games on Physical Frailty Components in Institutionalized Older Adults Jerónimo J. González-Bernal 1 , Maha Jahouh 1,* , Josefa González-Santos 1,*, Juan Mielgo-Ayuso 1,* , Diego Fernández-Lázaro 2,3 and Raúl Soto-Cámara 1 1 Department of Health Sciences, University of Burgos, 09001 Burgos, Spain; [email protected] (J.J.G.-B.); [email protected] (R.S.-C.) 2 Department of Biochemistry, Molecular Biology and Physiology, Faculty of Health Sciences, Campus of Soria, University of Valladolid, 42003 Soria, Spain; [email protected] 3 Neurobiology Research Group, Faculty of Medicine, University of Valladolid, 47005 Valladolid, Spain * Correspondence: [email protected] (M.J.); [email protected] (J.G.-S.); [email protected] (J.M.-A.) Abstract: Aging is a multifactorial physiological phenomenon in which cellular and molecular changes occur. These changes lead to poor locomotion, poor balance, and an increased falling risk. This study aimed to determine the impact and effectiveness of the use of the Wii® game console on improving walking speed and balance, as well as its influence on frailty levels and falling risk, in older adults. A longitudinal study was designed with a pretest/post-test structure. The study population comprised people over 75 years of age who lived in a nursing home or attended a day care center (n = 80; 45 women; 84.2 ± 8.7 years). Forty of them were included in the Wii group (20 rehabilitation sessions during 8 consecutive weeks), and the other 40 were in the control group. -

Research Article Exergaming Can Be a Health-Related Aerobic Physical Activity

Hindawi BioMed Research International Volume 2019, Article ID 1890527, 7 pages https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/1890527 Research Article Exergaming Can Be a Health-Related Aerobic Physical Activity Jacek PolechoNski ,1 MaBgorzata Dwbska ,1 and PaweB G. Dwbski2 1 Department of Tourism and Health-Oriented Physical Activity, Te Jerzy Kukuczka Academy of Physical Education, Katowice, 40-065, Poland 2Chair and Clinical Department of Psychiatry, School of Medicine with the Division of Dentistry in Zabrze, Medical University of Silesia in Katowice, Poland Correspondence should be addressed to Małgorzata Dębska; [email protected] Received 14 March 2019; Revised 10 May 2019; Accepted 20 May 2019; Published 4 June 2019 Academic Editor: Germ´an Vicente-Rodriguez Copyright © 2019 Jacek Polecho´nski et al. Tis is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Te purpose of the study was to assess the intensity of aerobic physical activity during exergame training sessions with a moderate (MLD) and high (HLD) level of difculty of the interactive program “Your Shape Fitness Evolved 2012” for Xbox 360 Kinect in the context of health benefts. Te study involved 30 healthy and physically ft students. During the game, the HR of the participants was monitored using the Polar M400 heart rate monitor. Te average percentage of maximum heart rate (%HRmax) and heart rate reserve (%HRR) during the game was calculated and referred to the criterion of intensity of aerobic physical activity of American College of Sports Medicine and World Health Organization health recommendations. -

Nintendo Co., Ltd

Nintendo Co., Ltd. Financial Results Briefing for the Nine-Month Period Ended December 2008 (Briefing Date: 2009/1/30) Supplementary Information [Note] Forecasts announced by Nintendo Co., Ltd. herein are prepared based on management's assumptions with information available at this time and therefore involve known and unknown risks and uncertainties. Please note such risks and uncertainties may cause the actual results to be materially different from the forecasts (earnings forecast, dividend forecast and other forecasts). Nintendo Co., Ltd. Consolidated Statements of Income Transition million yen FY3/2005 FY3/2006 FY3/2007 FY3/2008 FY3/2009 Apr.-Dec.'04 Apr.-Dec.'05 Apr.-Dec.'06 Apr.-Dec.'07 Apr.-Dec.'08 Net sales 419,373 412,339 712,589 1,316,434 1,536,348 Cost of sales 232,495 237,322 411,862 761,944 851,283 Gross margin 186,877 175,017 300,727 554,489 685,065 (Gross margin ratio) (44.6%) (42.4%) (42.2%) (42.1%) (44.6%) Selling, general, and administrative expenses 83,771 92,233 133,093 160,453 183,734 Operating income 103,106 82,783 167,633 394,036 501,330 (Operating income ratio) (24.6%) (20.1%) (23.5%) (29.9%) (32.6%) Other income 15,229 64,268 53,793 37,789 28,295 (of which foreign exchange gains) (4,778) (45,226) (26,069) (143) ( - ) Other expenses 2,976 357 714 995 177,137 (of which foreign exchange losses) ( - ) ( - ) ( - ) ( - ) (174,233) Income before income taxes and extraordinary items 115,359 146,694 220,713 430,830 352,488 (Income before income taxes and extraordinary items ratio) (27.5%) (35.6%) (31.0%) (32.7%) (22.9%) Extraordinary gains 1,433 6,888 1,047 3,830 98 Extraordinary losses 1,865 255 27 2,135 6,171 Income before income taxes and minority interests 114,927 153,327 221,734 432,525 346,415 Income taxes 47,260 61,176 89,847 173,679 133,856 Minority interests -91 -34 -29 -83 35 Net income 67,757 92,185 131,916 258,929 212,524 (Net income ratio) (16.2%) (22.4%) (18.5%) (19.7%) (13.8%) - 1 - Nintendo Co., Ltd. -

Assessing Older Adults' Usability Challenges Using Kinect-Based

Assessing Older Adults’ Usability Challenges Using Kinect-Based Exergames Christina N. Harrington1, Jordan Q. Hartley1, Tracy L. Mitzner1, and Wendy A. Rogers1 1Georgia Institute of Technology Human Factors and Aging Laboratory, Atlanta, GA {[email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]} Abstract. Exergames have been growing in popularity as a means to get physical exercise. Although these systems have many potential benefits both physically and cognitively, there may be barriers to their use by older adults due to a lack of design consideration for age-related changes in motor and perceptual capabilities. In this paper we evaluate the usability challenges of Kinect-based exergames for older adults. Older adults rated their interaction with the exergames system based on their perceived usefulness and ease-of-use of these systems. Although many of the participants felt that these systems could be potentially beneficial, particularly for exercise, there were several challenges experienced. We discuss the implications for design guidelines based on the usability challenges assessed. Keywords: older adults, exergames, usability, interface evaluation 1 Introduction The use of commercially designed exergames for physical activity has become widely accepted among a large audience of “wellness gamers” as a means of cognitive and physical stimulation [1]. Exergames are defined as interactive, exercise-based video games where players engage in physical activity via an onscreen interface [2]. These games can be played at home via a player interacting with a computer-simulated competitor, or in a multiplayer mode to encourage social connectivity. Exergames use body movement and gestures as input to responsive motion-detection consoles such as the Nintendo Wii and Balance Board, or Microsoft Xbox 360 with Kinect. -

Exergames and the “Ideal Woman”

Make Room for Video Games: Exergames and the “Ideal Woman” by Julia Golden Raz A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Communication) in the University of Michigan 2015 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Christian Sandvig, Chair Professor Susan Douglas Associate Professor Sheila C. Murphy Professor Lisa Nakamura © Julia Golden Raz 2015 For my mother ii Acknowledgements Words cannot fully articulate the gratitude I have for everyone who has believed in me throughout my graduate school journey. Special thanks to my advisor and dissertation chair, Dr. Christian Sandvig: for taking me on as an advisee, for invaluable feedback and mentoring, and for introducing me to the lab’s holiday white elephant exchange. To Dr. Sheila Murphy: you have believed in me from day one, and that means the world to me. You are an excellent mentor and friend, and I am truly grateful for everything you have done for me over the years. To Dr. Susan Douglas: it was such a pleasure teaching for you in COMM 101. You have taught me so much about scholarship and teaching. To Dr. Lisa Nakamura: thank you for your candid feedback and for pushing me as a game studies scholar. To Amy Eaton: for all of your assistance and guidance over the years. To Robin Means Coleman: for believing in me. To Dave Carter and Val Waldren at the Computer and Video Game Archive: thank you for supporting my research over the years. I feel so fortunate to have attended a school that has such an amazing video game archive. -

Validity and Reliability of Wii Fit Balance Board for the Assessment of Balance of Healthy Young Adults and the Elderly

J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 25: 1251–1253, 2013 Validity and Reliability of Wii Fit Balance Board for the Assessment of Balance of Healthy Young Adults and the Elderly WEN-DIEN CHANG, PhD1), WAN-YI CHANG, MS2), CHIA-LUN LEE, PhD3), CHI-YEN FENG, MD4)* 1) Department of Sports Medicine, China Medical University, Taiwan (ROC) 2) Graduate Institute of Networking and Multimedia, National Taiwan University, Taiwan (ROC) 3) Center for General Education, National Sun Yat-sen University, Taiwan (ROC) 4) Department of General Surgery, Da Chien General Hospital: No. 36, Gongjing Road, Miaoli City, Miaoli County, Taiwan (ROC) Abstract. [Purpose] Balance is an integral part of human ability. The smart balance master system (SBM) is a balance test instrument with good reliability and validity, but it is expensive. Therefore, we modified a Wii Fit bal- ance board, which is a convenient balance assessment tool, and analyzed its reliability and validity. [Subjects and Methods] We recruited 20 healthy young adults and 20 elderly people, and administered 3 balance tests. The corre- lation coefficient and intraclass correlation of both instruments were analyzed. [Results] There were no statistically significant differences in the 3 tests between the Wii Fit balance board and the SBM. The Wii Fit balance board had a good intraclass correlation (0.86–0.99) for the elderly people and positive correlations (r = 0.58–0.86) with the SBM. [Conclusions] The Wii Fit balance board is a balance assessment tool with good reliability and high validity for elderly people, and we recommend it as an alternative tool for assessing balance ability. -

Effect of the Wii Sports Resort on the Improvement in Attention

Unibaso-Markaida et al. Journal of NeuroEngineering and Rehabilitation (2019) 16:32 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12984-019-0500-5 RESEARCH Open Access Effect of the Wii Sports Resort on the improvement in attention, processing speed and working memory in moderate stroke Iratxe Unibaso-Markaida* , Ioseba Iraurgi, Nuria Ortiz-Marqués, Imanol Amayra and Silvia Martínez-Rodríguez Abstract Background: Stroke is the most common neurological disease in the world. After the stroke, some people suffer a cognitive disability. Commercial videogames have been used after stroke for physical rehabilitation; however, their use in cognitive rehabilitation has hardly been studied. The objectives of this study were to analyze attention, processing speed, and working memory in patients with moderate stroke after an intervention with Wii Sports Resort and compared these results with a control group. Methods: A pre-post design study was conducted with 30 moderate stroke patients aged 65 ± 15. The study lasted eight weeks. 15 participated in the intervention group and 15 belong to the control group. They were assessed in attention and processing speed (TMT-A and B) and working memory (Digit Span of WAIS-III). Parametric and effect size tests were used to analyze the improvement of those outcomes and compared both groups. Results: At the baseline, there was no difference between TMT-A and B. A difference was found in the scalar score of TMT-B, as well as in Digit Backward Span and Total Digit Task. In TMT-A and B, the intervention group had better scores than the control group. The intervention group in the Digit Forward Span and the Total Digit obtained a moderate effect size and the control group also obtained a moderate effect size in Total Digit. -

Nintendo's Wii Fit Overestimates Distance

Science and Technology How Far Did Wii Run? Nintendo’s Wii Fit Overestimates Distance Shayna Moratt*, Carmen B. Swain Department of Exercise Science, The Ohio State University College of Education and Human Ecology ‘Exergaming’ (performing exercise utilizing an interactive video game) has become a popular form of physical activity. Some exergames are specifi- cally aimed at improving or maintaining physical fitness. Yet, there is little information available to describe the accuracy of feedback given to partic- ipants. PURPOSE: To examine the reported run distance and exercise in- tensity elicited by the Wii Fit aerobic free run. METHODS: 500 participants ages 10- 49 completed the Wii Fit aerobic free run. Oxygen consumption (VO2) was measured. Relative oxygen consumption values were used to determine estimated run distance based upon American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) metabolic equations. Subjects rated perceived exertion using Borg’s scale at a period of every 5 minutes.RESULTS: The Wii Fit overestimated the distance of the aerobic free run by a percentage differ- ence of 49.9 ± 15.7 percent. The average VO2 during the free run was 22.3 ± 5.8 ml/kg/min or 6.4 ± 1.7 METs, which is considered vigorous in- tensity by ACSM standards. The mean RPE recorded was 12.43 ± 2.46. CONCLUSIONS: The Wii Fit displays an overestimated figure for dis- tance when performing the aerobic free run. However, the general level of intensity in this sizeable population shows promise as a method of ex- ercise appropriate to improve or maintain fitness in various populations. Introduction BASS, 2010). Frequent participation in physi- About the Author: Physical activity is defined as any body cal activity contributes to ones physical fitness. -

THE EFFECTS of the WII FIT PLUS on BONE MINERAL DENSITY and FLEXIBILITY in ADULTS a Thesis Presented to the Graduate Faculty Of

THE EFFECTS OF THE WII FIT PLUS ON BONE MINERAL DENSITY AND FLEXIBILITY IN ADULTS A Thesis Presented to The Graduate Faculty of The University of Akron In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science Nicholas T. Potenzini May, 2011 THE EFFECTS OF THE WII FIT PLUS ON BONE MINERAL DENSITY AND FLEXIBILITY IN ADULTS Nicholas T. Potenzini Thesis Approved: Accepted: __________________________ __________________________ Advisor Dean of the College Dr. Judith Juvancic-Heltzel Dr. Mark Shermis __________________________ __________________________ Committee Member Dean of the Graduate School Dr. Ronald Otterstetter Dr. George Newkome __________________________ __________________________ Committee Member Date Rachele Kappler __________________________ Department Chair Dr. Victor Pinheiro ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF TABLES………………………………………………………………………..v LIST OF FIGURES………………………………………………………………………vi CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTION……………………………………………………….……….......1 II. REVIEW OF LITERATURE……………………………..…………….………..….. 4 III. METHODS……………………………………...…………………………….….…. 8 Participants……………………………….…………………..…………………..8 Program Design………………………………………………..….………….….11 Statistical Design……………………………………….…………..……….…...13 IV. RESULTS……………………………………………...………………….……..…..14 V. SUMMARY………………………………………...………………………..………18 REFERENCES……………………………………………………………………..……21 APPENDICES .................................................................................................................. 24 Appendix A. Human Subjects Approval Form………………………………… 26 Appendix -

Nintendo Wii Versus Resistance Training to Improve Upper-Limb Function in Children Ages 7 to 12 with Spastic Hemiplegic Cerebral Palsy: a Home-Based Pilot Study

Nintendo Wii versus Resistance Training to Improve Upper-Limb Function in Children Ages 7 to 12 with Spastic Hemiplegic Cerebral Palsy: A Home-Based Pilot Study By Caroline Kassee A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Health Sciences In The Faculty of Health Sciences Kinesiology University of Ontario Institute of Technology July 2015 © Caroline Kassee, 2015 ii CERTIFICATE OF APPROVAL Caroline Kassee (2015) iii Nintendo Wii versus Resistance Training to Improve Upper- Limb Function in Children Ages 7 to 12 with Spastic Hemiplegic Cerebral Palsy: A Home-Based Pilot Study Chairperson of the Supervisory Committee: Dr. Meghann Lloyd Faculty of Health Sciences Abstract This pilot, home-based study compared a Nintendo Wii intervention to a single-joint upper-limb resistance training of a similar intensity, in n=6 children ages of 7 to 12 with spastic hemiplegic CP with respect to upper limb function, compliance and motivation levels. The main results of this study found that all participants in the Wii intervention group (n=3) experienced positive changes in more than one assessment from pre-test to follow-up, and these changes were on average greater than those experienced by the resistance training group (n=3). Also, the Nintendo Wii group was found to have a higher compliance rate with the study’s protocols, and higher parent-reported motivation levels throughout the study, as compared to the resistance-training group. This suggests that Nintendo Wii interventions for the upper limbs may be a more effective home-based rehabilitation strategy than the single-joint upper limb resistance training program used in this study for this population, primarily due to greater participant motivation to comply with Nintendo Wii training.