LEGACIES: the Sublime WW40100

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

* "What Tech Skills Are Hot for 2006

Ειδήσεις για την ΑΣΦΑΛΕΙΑ στις ΤΠΕ απ’ όλο τον κόσμο... Δελτίο 91 23 Σεπτέμβρη 2007 UM Software Tools May Key Successful Antiterrorism, Military and Diplomatic Ac- tions, University of Maryland (09/13/07), L. Tune The University of Maryland Institute for Advanced Computer Studies (UMIACS) has deve- loped computer analysis software to provide rapid information on terrorists and the cultural and political climate on the ground in areas of critical interest. The new computer models and databases could help policymakers and military leaders predict the behavior of political, eco- nomic, and social groups. UMIACS director and professor of computer science V. Subrah- manian says US commanders probably knew where Osama bin Laden was, but were unable to capture him because troops on the group did not have enough cultural knowledge to suc- cessfully negotiate with the locals. Subrahmanian says such failures can be avoided if decisi- on makers have access to pertinent data and accurate models of behavior. The software tools developed by Subrahmanian and his colleagues track information on foreign groups in a vari- ety of sources, including news sources, blogs, and online video libraries. The software can al- most instantly search the entire Internet for information and links on a terrorist suspect or ot- her particular person, group, or other topic of interest. Additionally, with help from social scientists at the University of Maryland, UMIACS computer scientists developed methods to obtain rules governing the behaviors of different groups in foreign areas, including about 14,000 rules on Hezbollah alone. Scientists Use the "Dark Web" to Snag Extremists and Terrorists Online National Science Foundation (09/10/07) University of Arizona Artificial Intelligence Lab researchers have created the Dark Web pro- ject with the intention of systematically collecting and analyzing all terrorist-generated con- tent on the Web. -

The Elders Call on the World to Wake up to the Threats of Nuclear War and Climate Disaster As They Unveil the 2020 Doomsday Clock

The Elders call on the world to wake up to the threats of nuclear war and climate disaster as they unveil the 2020 Doomsday Clock WASHINGTON D.C., 23 January 2020 Mary Robinson, Chair of The Elders and former President of Ireland, and Ban Ki-moon, Deputy Chair of The Elders and former United Nations Secretary-General, today joined experts from the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists for the unveiling of the Doomsday Clock in Washington DC, an annual assessment of the existential risks faced by humanity. The Clock’s hands were moved forward to 100 seconds to midnight - the closest to midnight they have been since they were first set in 1947. The decision takes into account the precarious state of nuclear arms controls, the growing threat of climate disaster, and how these can be compounded by disruptive new technologies. “Our planet faces two concurrent existential threats: the climate crisis and nuclear weapons. We are faced by a gathering storm of extinction-level consequences, and time is running out,” Mary Robinson said. The Elders specifically called on President Trump to respond to Russian President Vladimir Putin’s offer to open negotiations on New START, which will expire in February 2021 unless the agreement between Washington and Moscow is extended. Following the termination of the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty in July 2019, the end of New START would mean there was no remaining arms control treaty in force between the United States and Russia, raising the prospect of a new nuclear arms race. The Elders reiterated their proposals for a “nuclear minimisation”i agenda as the best way of making progress towards complete disarmament by the five Permanent Members of the UN Security Council and all other nuclear powers. -

2019 JUNO Award Nominees

2019 JUNO Award Nominees JUNO FAN CHOICE AWARD (PRESENTED BY TD) Alessia Cara Universal Avril Lavigne BMG*ADA bülow Universal Elijah Woods x Jamie Fine Big Machine*Universal KILLY Secret Sound Club*Independent Loud Luxury Armada Music B.V.*Sony NAV XO*Universal Shawn Mendes Universal The Weeknd The Weeknd XO*Universal Tory Lanez Interscope*Universal SINGLE OF THE YEAR Growing Pains Alessia Cara Universal Not A Love Song bülow Universal Body Loud Luxury Armada Music B.V.*Sony In My Blood Shawn Mendes Universal Pray For Me The Weeknd, Kendrick Lamar Top Dawg Ent*Universal INTERNATIONAL ALBUM OF THE YEAR Camila Camila Cabello Sony Invasion of Privacy Cardi B Atlantic*Warner Red Pill Blues Maroon 5 Universal beerbongs & bentleys Post Malone Universal ASTROWORLD Travis Scott Sony ALBUM OF THE YEAR (SPONSORED BY MUSIC CANADA) Darlène Hubert Lenoir Simone* Select These Are The Days Jann Arden Universal Shawn Mendes Shawn Mendes Universal My Dear Melancholy, The Weeknd The Weeknd XO*Universal Outsider Three Days Grace RCA*Sony ARTIST OF THE YEAR (PRESENTED WITH APPLE MUSIC) Alessia Cara Universal Michael Bublé Warner Shawn Mendes Universal The Weeknd The Weeknd XO*Universal Tory Lanez Interscope*Universal GROUP OF THE YEAR (PRESENTED WITH APPLE MUSIC) Arkells Arkells*Universal Chromeo Last Gang*eOne Metric Metric Music*Universal The Sheepdogs Warner Three Days Grace RCA*Sony January 29, 2019 Page 1 of 9 2019 JUNO Award Nominees -

Nuclear Posture Review Takes a Further Look at the Issue by Placing the Idea of Nuclear Weapons As Useable Weapons More Fully in a LongerTerm Context

2.RogersJapanletters_Template.qxd 15/02/2018 10:12 Page 9 7 Nuclear Summary Posture North Korea and Russia may be the focus Review of contemporary Western fears of imminent nucleararmed conflict but development and deployment of ‘useable’ nuclear Sliding weapons has been a constant throughout the Towards atomic age and by all nucleararmed states. Nuclear Current revision of the United States’ War? declared nuclear posture is only the most visible manifestation of adjustments to all the main nuclear arsenals, with the UK at the vanguard of deploying technologies potentially calibrated for preemptive rather Paul Rogers than retaliatory strike. Introduction My August 2017 briefing, Limited Nuclear Wars – Myth and Reality, focused on the common misconception that nuclear weapons exist as ultimate deterrents against catastrophic attack and that, by maintaining the ability to retaliate, they therefore deter the initial aggression. Some of the emphasis of the briefing was on the UK’s position following the Prime Minister’s firm Paul Rogers is the Global declaration to Parliament that she was Security Consultant to prepared to ‘press the button’, but this was Oxford Research Group also in the wider context of the tensions that and Professor of Peace had arisen in USNorth Korean relations. Studies at the University of More recently, two developments have Bradford. His ‘Monthly added salience to the issue. One is the of Global Security Briefings’ details of the new US Nuclear Posture are available from Review which points to additional www.oxfordresearchgroup. circumstances that might prompt nuclear org.uk. His latest book first use such as a response to a nonnuclear Irregular War: ISIS and attack, and the other is the movement of the the New Threats from the ‘Doomsday Clock’ closer to midnight. -

112 It's Over Now 112 Only You 311 All Mixed up 311 Down

112 It's Over Now 112 Only You 311 All Mixed Up 311 Down 702 Where My Girls At 911 How Do You Want Me To Love You 911 Little Bit More, A 911 More Than A Woman 911 Party People (Friday Night) 911 Private Number 10,000 Maniacs More Than This 10,000 Maniacs These Are The Days 10CC Donna 10CC Dreadlock Holiday 10CC I'm Mandy 10CC I'm Not In Love 10CC Rubber Bullets 10CC Things We Do For Love, The 10CC Wall Street Shuffle 112 & Ludacris Hot & Wet 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says 2 Evisa Oh La La La 2 Pac California Love 2 Pac Thugz Mansion 2 Unlimited No Limits 20 Fingers Short Dick Man 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls 3 Doors Down Duck & Run 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3 Doors Down Its not my time 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 3 Doors Down Loser 3 Doors Down Road I'm On, The 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone 38 Special If I'd Been The One 38 Special Second Chance 3LW I Do (Wanna Get Close To You) 3LW No More 3LW No More (Baby I'm A Do Right) 3LW Playas Gon' Play 3rd Strike Redemption 3SL Take It Easy 3T Anything 3T Tease Me 3T & Michael Jackson Why 4 Non Blondes What's Up 5 Stairsteps Ooh Child 50 Cent Disco Inferno 50 Cent If I Can't 50 Cent In Da Club 50 Cent In Da Club 50 Cent P.I.M.P. (Radio Version) 50 Cent Wanksta 50 Cent & Eminem Patiently Waiting 50 Cent & Nate Dogg 21 Questions 5th Dimension Aquarius_Let the sunshine inB 5th Dimension One less Bell to answer 5th Dimension Stoned Soul Picnic 5th Dimension Up Up & Away 5th Dimension Wedding Blue Bells 5th Dimension, The Last Night I Didn't Get To Sleep At All 69 Boys Tootsie Roll 8 Stops 7 Question -

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Shakedown by Don Debrandt Don Debrandt's CYBERJUNK

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Shakedown by Don DeBrandt Don DeBrandt's CYBERJUNK. Don DeBrandt writes science fiction, fantasy, horror, superheroes, cyberpunk, cyberfolk, and cyberanything else. Spider Robinson has compared DeBrandt's fiction to that of Larry Niven and John Varley; his first novel, The Quicksilver Screen , made Locus magazine's recommended reading list for 1992. He's also published horror fiction in Pulphouse, a novella in the SF magazine Horizons , three short stories in the Weird West gaming anthology Deadlands, and written a bi-monthly column on the future of e-business for the magazine Backbone. His fiction has earned him Honorable Mentions in both the Year's Best SF and the Year's Best Fantasy and Horror. He has written three stage plays for high schools: Heart of Glass; Happy Hour at the Secret Hideout; and Stagecraft. DeBrandt has also worked as a freelancer for Marvel Comics on such titles as Spiderman 2099 and 2099 Unlimited. His other comics work include several stories for the anthology comic Freeflight. DeBrandt lives in Vancouver, BC, and is notorious in certain circles of Northwest Fandom (but not for his writing). His hobbies include leather- tasting, naked laughing gas hot tubbing, and being thrown off roofs by irate hotel security. He does not plan to run for office, ever. There are too many pictures. Foreign Editions. Italian. L'Uomo Dei Mondi Di Polvere (Steeldriver); Urania. L'Uomo Del Mondo Selvaggio (Timberjak); Urania. French. Interet commun (Shakedown); Fleuve Noir. Plongee Mortelle (Riptide); Fleuve Noir. Russian. The Closer; Redfish. Schedule. Don will be appearing at the New York Comicon at the Javits Center in New York City, From April 17-21, 2008. -

Keys to Healing & Deliverance

KEYS TO HEALING & DELIVERANCE By Bill Subritzky Proverbs 3:5-8 Trust in the LORD with all your heart, And lean not on your own understanding; In all your ways acknowledge Him, And He shall direct your paths. Do not be wise in your own eyes; Fear the LORD and depart from evil. It will be health to your flesh, And strength to your bones. 1. We should be born again: John 3:3 Jesus answered and said to him, "Most assuredly, I say to you, unless one is born again, he cannot see the kingdom of God." This means that we must surrender our lives absolutely to Jesus Christ turning from darkness to light from the power of Satan to the power of God. 2. We should repent from all sin: This means that we must absolutely renounce all sin turning completely away from it. Sin is defined as follows: Fornication (having sex outside of marriage) Idolatry (placing other things before God, e.g. having other gods or idolising persons and/or things ahead of God) Adultery Homosexuality Sodomy Thieving Covetousness (lustful desire for the property of others and greedy for gain) Reviling (cursing) Extortion Uncleanness e.g. bad language Lewdness e.g. pornography, bestiality Envy Hatred 1 Contentions (causing fights) Jealousies Outbursts of wrath Foolish talking Coarse jesting, i.e. dirty jokes Selfish ambitions Dissension (causing discord among the brethren) Drunkenness Revelries e.g. wild parties Cowardly (i.e. not following Jesus Christ) Murder e.g. unnecessary abortion Lying The unbelieving The abominable Heresies (e.g. Mormons and Jehovah’s Witnesses) Sorcery -

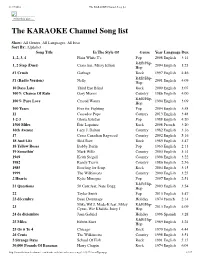

The KARAOKE Channel Song List

11/17/2016 The KARAOKE Channel Song list Print this List ... The KARAOKE Channel Song list Show: All Genres, All Languages, All Eras Sort By: Alphabet Song Title In The Style Of Genre Year Language Dur. 1, 2, 3, 4 Plain White T's Pop 2008 English 3:14 R&B/Hip- 1, 2 Step (Duet) Ciara feat. Missy Elliott 2004 English 3:23 Hop #1 Crush Garbage Rock 1997 English 4:46 R&B/Hip- #1 (Radio Version) Nelly 2001 English 4:09 Hop 10 Days Late Third Eye Blind Rock 2000 English 3:07 100% Chance Of Rain Gary Morris Country 1986 English 4:00 R&B/Hip- 100% Pure Love Crystal Waters 1994 English 3:09 Hop 100 Years Five for Fighting Pop 2004 English 3:58 11 Cassadee Pope Country 2013 English 3:48 1-2-3 Gloria Estefan Pop 1988 English 4:20 1500 Miles Éric Lapointe Rock 2008 French 3:20 16th Avenue Lacy J. Dalton Country 1982 English 3:16 17 Cross Canadian Ragweed Country 2002 English 5:16 18 And Life Skid Row Rock 1989 English 3:47 18 Yellow Roses Bobby Darin Pop 1963 English 2:13 19 Somethin' Mark Wills Country 2003 English 3:14 1969 Keith Stegall Country 1996 English 3:22 1982 Randy Travis Country 1986 English 2:56 1985 Bowling for Soup Rock 2004 English 3:15 1999 The Wilkinsons Country 2000 English 3:25 2 Hearts Kylie Minogue Pop 2007 English 2:51 R&B/Hip- 21 Questions 50 Cent feat. Nate Dogg 2003 English 3:54 Hop 22 Taylor Swift Pop 2013 English 3:47 23 décembre Beau Dommage Holiday 1974 French 2:14 Mike WiLL Made-It feat. -

Titelliste Rollercoaster 1 1. Jethro Tull: Teacher 2

Titelliste Rollercoaster 1 1. Jethro Tull: Teacher 2. Frijid Pink: House of the rising sun 3. Mandrill: Mandrill 4. Chris Rea: The road to hell 5. GesmbH: Move on 6. Roger Chapman: Moth of a flame 7. Wah Wah Watson: Goo goo wah wah 8. Temptations: Aint no justice 9. Juicy Lucy: Willie the pimp 10. Cressida: Munich 11. Leon Redbone: My walking stick Titelliste Rollercoaster 2 1. Steppenwolf: Born to be wild 2. Family: The weavers answer 3. Kevin Ayers: Heartbreak hotel 4. Weather Report: Black market 5. Golden Earring: The wall of dolls 6. Stooges: Down the street 7. Pink Floyd: Let there be more light 8. Chicago: I'm a man 9. Gentle Giant: The house, the street, the room 10. King Crimson: In the court of the crimson king 11. Leon Redbone: Somebody stole my gal Titelliste Rollercoaster 3 1. Black Sabbath: Paranoid 2. Pat Martino: Deeda 3. Camel: Slow yourself down 4. Frank zappa: Muffin man 5. Pete Brown & Piblokto: Station song platform two 6. Chase: Bochawa 7. Deep Purple: No no no 8. Electric Flag: Sunny 9. Iron Butterfly: In a gaddda da vida 10. Leon Redbone: Desert blues Titelliste Rollercoaster 4 1. Jimi Hendrix: All along the watchtower 2. Barclay James Harvest: Ball and chain 3. El Chicano: I'm a good woman 4. Bob Dylan: Knocking on heavens door 5. Quicksilver Messenger Service: Fresh air 6. Passport: Jadoo 7. Blood, Sweat & Tears: Hi-de-Ho 8. Walpurgis: Queen of Saba 9. Climax Blues Band: Amerita/Sense of direction 10. Beggars Opera: Light cavalry 11. -

ALLIANCE SUMMER 2013 SALE BOOK Quantities Are Limited, Prices

ALLIANCE SUMMER 2013 SALE BOOK Quantities are limited, prices good while supply lasts Sale ends Friday, August 16, 2013 Contact your Account Rep or order online at retailerservices.alliance-games.com Stock Code Description Price Discount SALE PRICE AAG FOFCD1 FOF Fog of War Deck $18.00 80 $3.60 ADV DMGK003 Magikano V3 (DVD) $29.98 95 $1.50 APL 0818 THIRD REICH: RUMORS OF WAR $29.99 80 $6.00 APL 0822 GWAS: SEA OF TROUBLES $29.99 80 $6.00 APL 1808 Panzer Grenadier: North of Elsenborn $9.99 85 $1.50 APL 1816 Panzer Grenadier: Siegfried Line $9.99 80 $2.00 APL 1823 PG: Divizione Corazzata $9.99 75 $2.50 ARY GG-SP1 Armory Spray Primer (White) $5.95 52 $2.86 ARY GG-SP2 Armory Spray Primer (Grey) $5.95 52 $2.86 ARY GG-SP3 Armory Spray Primer (Black) $5.95 52 $2.86 ARY GG-SPM Armory Spray Primer (Matte Sealer) $5.95 52 $2.86 ASI FE01 Fealty $30.00 75 $7.50 ASM 49765 Space Pirates $59.99 75 $15.00 ASM 700500 Lady Alice $42.99 60 $17.20 ASM AGE01US Age Of Gods $39.99 75 $10.00 ASM ALP01US Expedition Altiplano $19.99 70 $6.00 ASM BBQ01US Barbeque Party $19.99 75 $5.00 ASM CARO01US Carole $14.99 70 $4.50 ASM DIX03US Dixit: Odyssey (expansion) $29.99 65 $10.50 ASM DIXJ01 Dixit Jinx (stand alone) $14.99 70 $4.50 ASM DM01US Draco Mundis Board Game $32.99 80 $6.60 ASM DRAG001 River Dragons $39.99 52 $19.20 ASM DT02US Dungeon Twister: Paladins & Dragons $21.99 65 $7.70 ASM ECL02 Eclipse: Rise Of The Ancients Expansion $49.99 52 $24.00 ASM ECLI01 Eclipse: New Dawn For The Galaxy $99.99 52 $48.00 ASM EYE01US Eye For An Eye $12.99 75 $3.25 ASM FD04US Formula -

Penticton Reads Ballots Results Bad - Good 1 - 5 Title Author Rating Comments Brava Valentine a Trigiani 3 the Woman in the Window A

Penticton Reads Ballots Results Bad - Good 1 - 5 Title Author Rating Comments Brava Valentine A Trigiani 3 The Woman in the Window A. J. Finn 4 First rate mystery/thriller! lots of parts to skip through as writing repetitive and darkness before dawn ace collins 2 unnecessary The Great Nadar Adam Begley 4 Intersting man, colourful and talented Kiss Carlo Adriana Trigiani 4 An intriguing storyline. Started re-reading. Intense and emotional story. Very different women come together in a "Mommy" group to share their experience and support each other as they navigate life being first-time mothers with newborn babies. Tragedy draws them closer but no one is prepared when secrets are revealed. Lots of twists The Perfect Mother: A Novel Aimee Molloy 4 and turns before a surprising ending. Truth Al Franken 4 If you were here Alafair Burke 5 Things I Overheard While … Alan Alda 5 Turned into an amusing writer Excellent very detailed but easy to read about early history of A savage empire alan axelrod 5 North America A book from my book shelf about reirement and how to Advance to go Alan Dickson 3 prepare, over simplistic and not realistic in 2018! Murder Most Malicious Alyssa Maxwell 4 BREATH OF FIRE AMANDA BOUCHET 5 LOTS OF ACTION AND ROMANCE lethal licorice amanda flower 5 Death's daughter Amber Benson 5 lots of action A gentleman in Moscow Amor Towle 5 Interesting, sad and funny. Enjoyable the rift frequency amy foster 3 Not a fast read, but extremely interesting.Every human emotion The Valley of Amazement Amy Tan 5 is in this book. -

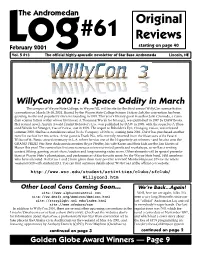

Andromedan Log 61 Master

The Andromedan Original #61 Reviews Log starting on page 40 February 2001 Vol. 5 #13 The official highly-sporadic newsletter of Star Base Andromeda Lincoln, NE WillyCon 2001: A Space Oddity in March The campus of Wayne State College, in Wayne NE, will be site for the third annual WillyCon science fiction convention on March 16-18, 2001. Hosted by the Wayne State College Science Fiction club, the convention has been growing in size and popularity since its founding in 1999. This year’s literary guest is author Julie Czerneda, a Cana- dian science fiction writer whose first novel, A Thousand Words for Stranger, was published in 1997 by DAW Books. Her second novel, Aurora Award Finalist Beholder’s Eye, was published by DAW in 1998, with the sequel to A Thou- sand Words for Stranger, Ties of Power, out in 1999. The sequel to Beholder’s Eye, Changing Vision, was released summer 2000. She has a standalone called In the Company of Others, coming June 2001. DAW has purchased another novel in each of her two series. Artist guest is Frank Wu, who recently returned from the Illustrators of the Future/ Writers of the Future award ceremony in L.A. where he was one of the 10 quarterly art winners - and he also won the GRAND PRIZE! Star Base Andromeda member Bryce Pfeiffer, his wife Karen and their kids are the Fan Guests of Honor this year! The convention features numerous science-oriented panels and workshops, as well as a writing contest, filking, gaming, an art show/auction and long-running video room.