We Measure Satisfaction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Saginaw Low Sodium Commissary Menu

Saginaw Low Sodium Commissary Menu **You will be charged a Commissary Order Fee with each order placed *Only one order per person* Wednesday, October 14, 2020 Code Product Name Max Price Code Product Name Max Price Code Product Name Max Price BEVERAGES 503 SALTED PEANUTS 3.5 oz $1.73 650 LEMONADE DRINK SUGAR FREE 1.4 g $0.27 5411 TRAIL MIX SWEET N SALTY 3.5 oz $2.00 651 PUNCH DRINK SUGAR FREE 1.4 g $0.27 649 SANKA DECAF COFFEE ss $0.40 5421 SALTED CARMEL DELIGHT 5.5 oz $4.51 652 ICED TEA SUGAR FREE 1.4 g $0.27 656 SS INSTANT COFFEE MAXWELL HOUSE $0.40 6055 LAYS SOUR CREAM & ONION CHIPS 1.5 oz $1.73 6561 DR INSTANT COFFEE 4 oz $4.54 CLOTHING 6057 CHEDDARCORN & CARAMEL 1.7 oz $1.99 657 SWISS MISS HOT CHOCOLATE .73 oz $0.52 841 TUBE SOCKS 1 pair $1.82 690 SALTINES-BOX 16 oz $4.40 6599 MAXWELLHOUSE INSTANT COFFEE 4 oz $9.78 8435 BLACK T-SHIRT L $9.56 691 SNACK CRACKERS - BOX 10.3 oz $5.97 6603 FRENCH VANILLA COFFEE 3 oz $5.04 8436 BLACK T-SHIRT XL $9.56 692 GRAHAM CRACKERS -BOX 14.4 oz $6.31 6604 HAZELNUT COFFEE 3 oz $5.04 8437 BLACK T-SHIRT 2XL $13.20 665 MILK CHOCOLATE 8 oz $4.58 CONDIMENTS 8439 BLACK T-SHIRT 4XL $16.83 669 WHITE MILK 8 oz $4.58 587 RELISH PACKET 9 gm $0.29 8441 BLACK GYM SHORTS MED $25.02 BREAKFAST ITEMS 590 MAYONNAISE PACKET 12 gm $0.42 8442 BLACK GYM SHORTS LRG $25.02 620 JELLY SQUEEZE 1 oz $0.51 8443 BLACK GYM SHORTS XL $25.02 6012 BLUEBERRY MINI MUFFIN 1.7 oz $1.36 8451 LONGJOHNS SMALL 1 pair $17.04 6016 PECAN TWIRLS 3 pk $1.88 COOKIES & SWEETS 8452 LONGJOHNS MEDIUM 1 pair $17.04 634 TOASTER PASTRIES STRAWBERRY 2 pk -

Cakes Cookies/Brownies Truffles Meltaways

CAKES FLAVOR SLICE CAKE FLAVOR SLICE CAKE FLAVOR SLICE CAKE Aunt Ettas 9.95 75.00 Oreo Cheesecake 6.95 55.00 Bayou City Mud 5.95 45.00 Tres Leches 6.95 55.00 Carrot Cake 7.95 65.00 Turtle Fudge Cheesecake 6.95 55.00 Uncle Darryl 9.95 75.00 Tuxedo Cheesecake 6.95 55.00 New York style Cheesecake 8.95 65.00 Strawberry Cake 7.95 65.00 Wedding Cake 9.95 75.00 Pecan Pie 7.95 65.00 Tiramisu 6.95 55.00 German Chocolate 7.95 65.00 Truffle 6.95 55.00 Red Velvet 7.95 65.00 Bodacious Brownie 6.95 55.00 Boston Cream 6.95 55.00 Any Days a Holiday 9.95 75.00 Black Russian 6.95 55.00 COOKIES/BROWNIES FLAVOR PRICE FLAVOR PRICE FLAVOR PRICE Triple Chocolate 2.49 Oatmeal Raisin 2.49 Blondie Brownie 2.95 M&M 2.49 Vanilla Chip Macadamia 2.49 Reese’s Peanut Butter Cup Brownie 2.95 Reese’s Peanut Butter Cup 2.49 Double Fudge Chocolate Brownie 2.95 Chaos 2.49 Pecan Brownie 2.95 TRUFFLES FLAVOR PRICE FLAVOR PRICE FLAVOR PRICE Tiramisu 1.95 Oreo 1.95 Cheesecake 1.95 Champagne 1.95 Coconut 1.95 Cappuccino 1.95 Rum 1.95 Chocolate Mousse 1.95 Dark Sea Salt 1.95 Cotton Candy 1.95 Pecan Praline 1.95 Chocolate Sea Salt 1.95 Red Velvet 1.95 Peach 1.95 Mint 1.95 Hazelnut 1.95 Rasberry 1.95 Triple Cream Truffle 1.75 CLUSTERS MELTAWAYS TURTLES FUDGE FLAVOR PRICE FLAVOR PRICE FLAVOR PRICE FLAVOR PRICE Almond 1.75 Oreo 1.00 Almond 3.95 Chocolate 3.25 Cashew 1.75 Pecan 1.00 Cashew 3.95 Chocolate Nut Fudge 3.25 Peanut 1.75 Rice Krispy 1.00 Pecan 3.95 Peanut Butter Fudge 3.25 Pecan 1.75 Tiramisu Fudge 3.25 CHOCOLATE COVERED CANDY CANDY PRICE CANDY PRICE CANDY PRICE Almond Toffee -

Conference Trade Show Yellow Pages|Judith Manley

Judith Manley, Conference Trade Show Yellow Pages| Trade Show Director ACM AMP CORP meats, knockwurst kielbasa and Beans incl. LS Black, LS Pinto, LS Arnel Cayabyab Phillip Bennett sausages, premium roast beef, Garbanzo and LS Dark Red Kidneys. USDA choice corned beef, USDA Military Sales, West Coast 727-599-7369 BUTTER BUDS FOODSERVICE 619-952-0340 [email protected] choice pastrami, full ham category Jim Dodge [email protected] www.ampcorp.biz BOJA’S FOODS, INC. 800-361-7074 Tracy Boreman, Int’l Military Sales Dir. Cake, brownie, pancake, cookie, Kay Kramer [email protected] 803-445-4601 NFD milk mixes 251-824-4186; (C) 251-422-2674 www.bbuds.com [email protected] [email protected] Butter Buds, Buttermist, Garlic Lord Delrosario, ATEECO INC/MRS. T'S www.BojasFoods.com Buttermist, Alfredo Buds, Cheddar Military Sales, East Coast Michael Truax Domestic breaded shrimp, raw Buds 757-642-0447 724-473-0867 shrimp, stuffed shrimp, and crab [email protected] [email protected] cakes from Bayou La Batre, Ala- CAMBRO MANUFACTURING Jeff DeSantis, Nat’l Military Sales Dir. www.pierogies.com bama, a small fishing town on the COMPANY 843-995-5511 Mrs. T’s Pasta products, the perfect Gulf Coast. A United States Depart- Gayle Swain [email protected] pairing of pasta and potatoes; ment of Commerce Facility. 714-230-4317 www.afm-acm.com numerous varieties. [email protected] ACM Phone: 803-462-1919 AZAR NUT COMPANY BON CHEF, INC. www.cambro.com ACM Fax: 803-462-1918 Daniel Hayes Amy Passafaro Manufacturer of foodservice prod- ACM is a Master Military Broker Military Regional Manager 973-968-7138 ucts that encompass all aspects of covering international and national 540-327-6642 [email protected] foodservice operations. -

VS Web Pricebook Pastry

PASTRY Products Manufactured By - B&G 0.00 50‐200 B&G APPLE FRIED PIE 48 101 50‐201 B&G PEACH FRIED PIE 48 102 50‐202 B&G LEMON FRIED PIE 48 104 50‐203 B&G CHERRY FRIED PIE 48 103 50‐204 B&G CHOCOLATE FRIED PIE 48 105 50‐205 B&G MULTI PAK 48 106 50‐221 B&G CHOC/OATMEAL D‐LISH TREAT 24 221 Products Manufactured By - BIMBO 0.00 5‐717 BIMBO BARRITAS FRESA‐S‐BERRY 2 120 2717 5‐718 BIMBO BARRITAS PINA‐P‐APPLE 2C 120 2718 5‐719 BIMBO CANELITAS CINNAMON COOKI 81 2719 5‐727 BIMBO SPONCH‐MARSHMELLOW 3CT 96 2727 Products Manufactured By - BROAD STREET BAKERY 0.00 6‐100 BSB JUMBO HONEY BUN 5 OZ 36 13348150 6‐201 BSB 6‐PK SUGAR MINI DONUTS 72 13371452 6‐202 BSB RICH FRSTED MINI DONUTS 72 13348360 6‐203 BSB C‐NUT CRUNCH MINI DONUTS 72 13348310 6‐304 BSB APPLE TURNOVER 4.5 OZ 48 13373920 6‐308 BSB 2PK S'BERRY ANGEL FOOD CAK 36 13379372 6‐350 BSB DBLE CHOC CUPCAKES 4 OZ 36 13355012 6‐351 BSB 2PK BANANA PUDDING CUPCAKE 36 13350920 6‐352 BSB 2PK STRAWBERRY SHORTCAKE 36 13323930 6‐400 BSB CINN ROUND DANISH‐ 5 OZ 32 13336900 6‐470 BSB CINNAMON COFFEE CAKE 3.4OZ 36 13378800 6‐500 BSB FOA JUMBO H‐BUN 5 OZ 36 13348152 6‐601 BSB FOA 6‐PK SUGAR DONUTS 72 13370840 6‐602 BSB FOA 6‐PK FRSTED DONUTS 72 13348362 6‐603 BSB FOA C‐NUT CRNCH DONUTS 72 13348312 PASTRY Products Manufactured By - BROAD STREET BAKERY 0.00 6‐704 BSB FOA APPLE TURNOVER 4.5 OZ 48 13373922 6‐708 BSB FOA 2PK S'BERRY ANGEL CAKE 36 13379370 6‐750 BSB FOA DBLE CHOC C‐CAKES 36 13355160 6‐751 BSB FOA BAN PUDDING CUPCAKES 36 13350922 6‐752 BSB FOA S'BERRY SHORTCAKE CUPC 36 13323932 6‐800 BSB FOA CINN -

High Fructose Corn Syrup How Sweet Fat It Is by Dan Gill, Ethno-Gastronomist

High Fructose Corn Syrup How Sweet Fat It Is By Dan Gill, Ethno-Gastronomist When I was coming along, back in the ‘50s, soft drinks were a special treat. My father kept two jugs of water in the refrigerator so that one was always ice cold. When we got thirsty, we were expected to drink water. Back then Coke came in 6 ½ ounce glass bottles and a fountain drink at the Drug Store was about the same size and cost a nickel. This was considered to be a normal serving and, along with a Moon Pie or a nickel candy bar, was a satisfying repast (so long as it wasn’t too close to supper time). My mother kept a six-pack of 12-oz sodas in the pantry and we could drink them without asking; but there were rules. We went grocery shopping once a week and that six-pack had to last the entire family. You were expected to open a bottle and either share it or pour about half into a glass with ice and use a bottle stopper to save the rest for later, or for someone else. When was the last time you saw a little red rubber bottle stopper? Sometime in the late 70s things seemed to change and people, especially children, were consuming a lot more soft drinks. Convenience stores and fast food joints served drinks in gigantic cups and we could easily drink the whole thing along with a hamburger and French fries. Many of my friends were struggling with weight problems. -

TX Convenient Database

10/5/2012 Inventory Alphabetically Item No Item Name Cost Price Total Total Total Stock Cost Price 44700011607 0.00 3.89 0.00 0.00 0.00 797884770005 0.00 1.29 0.00 0.00 0.00 813805005008 0.00 0.25 0.00 0.00 0.00 72007 $.05 CHANGEMAKER 0.00 0.05 0.00 0.00 0.00 72014 $.10 CHANGEMAKER 0.00 0.10 0.00 0.00 0.00 72021 $.15 CHANGEMAKER 0.00 0.15 0.00 0.00 0.00 71994 $.20 CHANGEMAKER 0.00 0.20 0.00 0.00 0.00 72038 $.25 CHANGEMAKER 0.00 0.25 0.00 0.00 0.00 609470 $1 OFF CARTON CI 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 513401 $10 TEXMRT PHONE 0.00 10.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 513418 $20 TEXMART PHON 0.00 20.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 513999 $5 TXMART PHONEC 0.00 5.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 90446000283 004130000006+ 0.00 4.99 0.00 0.00 0.00 307667393057 1 0.00 1.49 0.00 0.00 0.00 9750982 1 LITER SINGLE D 0.00 1.59 0.00 0.00 0.00 490000501031 1 lt. coca cola 0.00 1.99 0.00 0.00 0.00 12000032257 1 LT. KAS 0.00 1.99 0.00 0.00 0.00 17 1.09 TACO 0.00 1.09 0.00 0.00 0.00 24 1.99 TACO 0.00 1.99 0.00 0.00 0.00 8938 10 LB ICE BAG EA 0.00 1.69 0.00 0.00 0.00 28000206604 100 GRAND 0.00 1.59 0.00 0.00 0.00 28000333454 100 GRAND 0.00 0.69 0.00 0.00 0.00 16916100239 100CT. -

Moonpiebanana-6Ct

Banana Moon Pie ICE CREAM INGREDIENTS: MILK, CREAM, MARSHMALLOW FLAVOR (CORN SYRUP, WATER, HIGH Nutrition Facts FRUCTOSE CORN SYRUP, Serving Size 1 Sandwich (82g) MODIFIED CORNSTARCH, NATURAL Servings Per Container 6 FLAVOR), SKIM MILK SOLIDS, SUGAR, CORN SYRUP, HIGH Amount Per Serving FRUCTOSE CORN SYRUP, BANANA Calories 270 Calories from Fat 130 PUREE (BANANA PUREE, CORN SYRUP, NATURAL AND ARTIFICIAL % Daily Value* FLAVORS, ANNATTO COLOR), WHEY, STABILIZER (MONO AND Total Fat 15g 23% DIGLYCERIDES, GUAR GUM, Saturated Fat 12g 60% CELLULOSE GUM AND CARRAGEENAN), NATURAL AND Trans Fat 0.5g ARTIFICIAL FLAVOR, ANNATTO COLOR. Cholesterol 15mg 5% Sodium 110mg 5% GRAHAM WAFER INGREDIENTS: ENRICHED WHEAT FLOUR (WHEAT Total Carbohydrate 34g 11% FLOUR, NIACIN, REDUCED IRON, THIAMIN MONONITRATE, Dietary Fiber 0g RIBOFLAVIN, FOLIC ACID), SUGAR, PARTIALLY HYDROGENATED Sugars 21g SOYBEAN OIL, GRAHAM FLOUR, Protein 3g HIGH FRUCTOSE CORN SYRUP, CORN STARCH, NATURAL FLAVOR, Vitamin A 4% • Vitamin C 0% BAKING SODA, SOY LECITHIN, MOLASSES. Calcium 6% • Iron 2% * Percent Daily Values are based on a 2,000 calorie diet. BANANA COATING INGREDIENTS: Your daily values may be higher or lower depending on COCONUT OIL, SUGAR, your caloric needs: HYDROGENATED COCONUT OIL, Calories: 2,000 2,500 SOYBEAN OIL, WHEY, Total Fat Less than 65g 80g CORNSTARCH, NONFAT DRY MILK, Sat Fat Less than 20g 25g TITANIUM DIOXIDE (FOR COLOR), Cholesterol Less than 300mg 300mg SOY LECITHIN, YELLOW #5 LAKE, Sodium Less than 2,400mg 2,400m NATURAL AND ARTIFICIAL FLAVOR, Total Carbohydrate 300g 375gg YELLOW #6 LAKE, RED #40 LAKE, Dietary Fiber 25g 30g BLUE #2 LAKE. CONTAINS: MILK, WHEAT, SOY . -

United States Patent (19) 11) Patent Number: 5,709,896 Hartigan Et Al

US005709896A United States Patent (19) 11) Patent Number: 5,709,896 Hartigan et al. 45 Date of Patent: Jan. 20, 1998 54 REDUCED-FAT FOOD DISPERSIONS AND 5,190,786 3/1993 Anderson et al.. METHOD OF PREPARNG 5,192,569 3/1993 McGinley et al.. 5,258,199 11/1993 Moore et al.. 75 Inventors: Susan Erin Hartigan, Franklin Park; 5,462,761 10/1995 McGinley et al. ...................... 426,574 Mark T. Izzo, Flemington; Carol A. Stahl, Princeton; Marlene T. Tuazon, FOREIGN PATENT DOCUMENTS Iselin, all of N.J. 9501729 1/1995 WIPO. 73) Assignee: FMC Corporation, Philadelphia, Pa. 9526643 10/1995 WIPO (21) Appl. No.: 665,625 Primary Examiner-Leslie Wong 22 Filed: Jun. 18, 1996 Attorney, Agent, or Firm-Polly E. Ramstad Related U.S. Application Data 57 ABSTRACT 60 Provisional application Nos. 60/001050 Jun. 23, 1995 and Reduced-fat food dispersions containing an aqueous disper 60/007,192 Nov. 1, 1995. sion of sugar and an aggregate of microcrystalline cellulose and a gum selected from galactomannan gum, glucomannan (51) Int. Cl. ................ A23G 1/00; A23G 3/00 52 U.S. C. ... ... 426/103; 426/573; 426/574; gum and mixtures thereof exhibit the ability to set, have 426/602; 426/658; 426/659; 426/660; 426/804 sugar bloom stability and mimic the rheology of full fat 58) Field of Search .............................. 426/89, 103, 573, chocolate coatings. These dispersions are useful, for 426/574, 575, 576,577, 658, 659, 660, example, in food coatings, food inclusions and fudge. A 804, 601, 602 method for setting of a high sugar content dispersion to a solid which solid is a soft or a firm solid at room temperature 56) References Cited is also provided. -

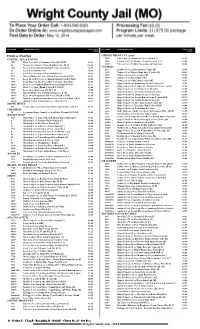

Wright County Jail - 2014 QTY ITEM# ITEM DESCRIPTION PRICE TOTAL QTY ITEM# ITEM DESCRIPTION PRICE TOTAL PRICE PRICE

QTY ITEM# ITEM DESCRIPTION PRICE TOTAL QTY ITEM# ITEM DESCRIPTION PRICE TOTAL PRICE PRICE FOOD & SNACKS CHEESE PRODUCTS (cont.) COFFEE, TEA & COCOA 5645 City Cow 4 oz. Mozzarella Cheese Stick [C G] $1.75 9655 Painted Cow 2 oz. Dippins Cream Cheese [C G S] $1.00 7022 Keefe 3 oz. 100% Colombian Coffee [K C R H] $3.81 10417 Velveeta 2 oz. Cheddar Cheese Spread 10 pk. [G] $5.56 50 Nescafe 8 oz. Taster's Choice Regular Coffee [K G] $16.38 7024 Keefe 3 oz. Decaffeinated Instant Coffee [K C R H] $4.75 COOKIES 229 Keebler 11.5 oz. Fudge Stripes Cookies [K] $3.69 21 Keefe 4 oz. Instant Coffee $2.69 4488 Nabisco 13 oz. Chewy Chips Ahoy! Cookies [K] $5.81 415 Keefe 8 oz. Tea Bags - 100 per box [K G S] $5.19 4592 Nabisco 14.3 oz. Oreo Cookies [K] $6.88 2974 Maxwell House 4 oz. Select Roast Coffee Pouch [K C R] $4.13 4593 Nabisco 16 oz. Nutter Butter [K] $6.94 7037 Keefe 10 oz. Hot Cocoa w/ Mini Marshmallows [K C R H] $2.06 4594 Nabisco 13 oz. Chips Ahoy! Cookies [K] $5.81 7495 Swiss Miss 9 oz. Hot Cocoa Mix (9 servings) [K C R G] $2.13 6068 Zippy Cakes 14 oz. Strawberry Creme Cookies [K] $2.19 10244 Keefe 3 oz. Colombian Blend Coffee Premium [K R H] $3.31 6069 Zippy Cakes 2.75 oz. Sugar Free Strawberry Creme... [K H] $1.00 10243 Keefe 3 oz. Alturo Blend Coffee [K C R H G] $3.06 6071 Zippy Cakes 6 oz. -

12-Mothers-Day-Recipes-For-Brunch

12 Mother’s Day Recipes for Brunch and Dessert: Blogger Edition 12 Mother’s Day Recipes for Brunch and Dessert: Blogger Edition Copyright 2011 by Prime Publishing LLC All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, without written permission from the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. Trademarks are property of their respective holders. When used, trademarks are for the benefit of the trademark owner only. Published by Prime Publishing LLC, 3400 Dundee Road, Northbrook, IL 60062 – www.primecp.com Find thousands of free recipes, cooking tips, entertaining ideas and more at http://www.RecipeLion.com/. 2 12 Mother’s Day Recipes for Brunch and Dessert: Blogger Edition Letter from the Editors Dear Cooking Enthusiast: Celebrate Mom this year by cooking or baking something fabulous for her. Rather than heading out to a restaurant, treat your Mom to something special at home; the effort will be all the more appreciated. You don’t need to be a cooking expert to try your hand at one of these brunch recipes and easy dessert recipes. You can start your Mother’s day out right by treating her to a delicious breakfast or brunch with these easy to follow and eye-catching recipes. Also with these decadent and easy dessert recipes you can finish her day off with something sweet. These Mother’s day recipes are everything you need to create a wonderful gift for Mom. -

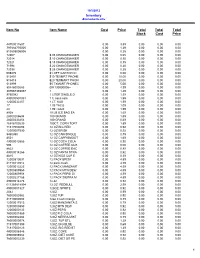

2014 Master FOOD Ohio QTY ITEM# ITEM DESCRIPTION WEIGHT TOTAL PRICE TOTAL QTY ITEM# ITEM DESCRIPTION WEIGHT TOTAL PRICE TOTAL WEIGHT PRICE WEIGHT PRICE

Ohio Food Package Program 2014 PRODUCT LIMITS 1 Beans - Limit 10 7 Chips & Snacks - Limit 10 13 Crackers - Limit 5 19 Noodles & Pasta - Limit 20 25 Poptarts - Limit 5 31 Soup Mixes - Limit 5 2 Breakfast Bars/Bagels - Limit 5 8 Coffee & Cappuccino - Limit 10 14 Creamer - Limit 2 20 Nuts, Popcorn & Snacks - Limit 20 26 Ramen Noodle - Limit 30 32 Sugar Substitute - Limit 2 3 Candy Bags - Limit 5 9 Cold Cereals - Limit 4 15 Drink Mixes - Limit 10 21 Pastries & Snack Cakes - Limit 10 27 Ready to Eat Meals - Limit 20 33 Tea - Limit 2 4 Candy Bars - Limit 36 10 Condiments - Individual Packets - Limit 50 16 Hot Cereal - Limit 5 22 Peanut Butter - Box - Limit 2 28 Rice - Limit 10 34 Tortillas - Limit 5 5 Candy Miscellaneous - Limit 4 11 Condiments - Squeeze Packets - Limit 5 17 Hot Chocolate & Cocoa - Limit 5 23 Peanut Butter - Limit 10 29 Seafood - Limit 15 35 Vegetables - Limit 30 6 Cheese Spreads & Sticks - Limit 5 12 Cookies - Limit 10 18 Meat Snacks & Jerky - Limit 20 24 Pickles - Limit 5 30 Seasonings - Limit 10 QTY ITEM# ITEM DESCRIPTION WEIGHT TOTAL PRICE TOTAL QTY ITEM# ITEM DESCRIPTION WEIGHT TOTAL PRICE TOTAL WEIGHT PRICE WEIGHT PRICE 2014 YEARLONG PROMOS (PICK ANY 2 PROMOTIONS WITH EVERY READY TO EAT MEALS (cont.) FOOD PURCHASE FOR FREE!) 3201 Armour 8 oz. Hot Chili w/Beans 27 8.2 oz. $1.75 42817 Ohio Seafood Kit **PROMO** 11, 13, 29 9.0 oz. 3203 Armour 8 oz. Beef Pot Roast 27 8.4 oz. $1.75 80000167 Ohio Coffee & Creamer Kit **PROMO** 8, 14 7.7 oz. -

Gustav Holst’S the Planets (P

Happy New Year! And welcome to HighNotes, brought to you by the Evanston Symphony for the senior members of our community who must of necessity isolate more because of COVID-19. The current pandemic has also affected all of us here at the ESO, and we understand full well the frustration of not being able to welcome the New Year with family and friends, take in a movie at a theatre, or even just talk to a friend over coffee or a neighbor down the hall. On the other hand, while we dearly miss performing for our fabu- Musical Notes and Activities for Seniors lous audiences, we certainly enjoy putting together these monthly from the Evanston Symphony Orchestra HighNotes for all of you! HighNotes always has some articles on a specific theme plus a variety of puzzles and often some really bad Music That’s Out of This World! jokes and puns. In this issue we highlight music that’s “Out of This World” and will take you on a musical trip to Outer Space. We’ll give Haydn The Creation 2 you a bit of information about Haydn’s The Creation followed by a lot of information about Gustav Holst’s The Planets (p. 2) and John Holst The Planets 2 Williams’ Star Wars (p. 8). The information on these last two is in the form of “easy listening” program notes, so you can use them Poor Pluto 4 when you listen to the music if you’d like. We also include a sheet called “HighNotes Links” so you can find the music on YouTube.